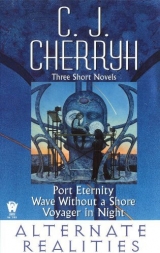

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

VOYAGER IN NIGHT

This book was one of those odd experiments aside from my works of wider appeal. Don and I discussed the outcome of the story—often. We absolutely disagreed on what happened. I find that a wonderful, whimsical kind of situation. Both of us certainly read the same book—well, he edited it and I wrote it—but both of us saw a different story at the end and both of us believed in what we saw.

Think of this as the kind of science fiction some writer might create who lived (or will live) at some time in the next half millennium, after we’ve gone to the stars. And will we still write science fiction then? I see no reason we won’t—Homer wrote science fiction, didn’t he? So did Dante. And Jules Verne. So do we. Why shouldn’t our descendants?

My job as a science fiction writer is only half about technology, the what-if and the what-next? Homer wrote about traveling beyond the rim of known seas, and meeting strange people. Dante used his science fiction writing for a political medium. Verne explored the future. And I’ve done a bit of each. But throughout all the meeting and the voyaging and the politicking and the imagining—I do the other thing those others did: I hold up a mirror to ourselves.

What would you do if you could live your life over—and over—and over?

What would you be if there were no end in sight?

Ever?

I

1,000,000 rise of terrene hominids

75,000 terrene ice age

35,000 hunter-gatherers

BC 9000 Jericho built

BC 3000 Sumer thriving

BC 1288 Reign of Rameses in Egypt

BC 753 founding of Rome

Trishanamarandu-keptawas, < >’s name, of shape subject to change and configurations of consciousness likewise mutable. But Trishanamarandu-keptawithin-the-shell kept alert against the threat of subversive alterations, for some of the guests aboard were unreliable in disposition and in sanity.

Concerning < >’s own mental stability, < > was reasonably certain. <> had a longer perspective than most and consequently held a different view of events. The chronometers which might, after so many incidents and so frequent transits into jumpspace, be subject to creeping inaccuracies, reported that the voyage had lasted more than 100,000 subjective ship-years thus far. This agreed with < >’s memory. Aberrations in both records were possible, but <> thought otherwise.

AD 1066 Battle of Hastings

AD 1492 Columbus

AD 1790 early Machine Age

AD 1800 Napoleonic Wars

AD 1903 Kitty Hawk

AD 1969 man on the moon

<> never slept. Some of the minds aboard might have seized control, given that opportunity, so <> managed <>’s body constantly, sometimes at a high level of mental activity, sometimes at marginal awareness, but <> never quite slept. Closest analogue to dreamstate, <> felt a slight giddiness during jumpspace transits. That was to be expected in a mind, even after long and frequent experience of such passages. < > leapt interstellar distances with something like sensual pleasure in the experience, whether the feeling came from the unsettling of < >’s mind or < >’s physical substance. Fear, after all, was a potent sensation; and all sensations were precious after so long a span of life.

<> traveled, that was what <> did.

<> set <>’s sights on whatever star was next and pursued it.

Another voyage began. Little Lindymoved up in the immense skeletal clutch of a Fargone loader into the cargo sling of the can-hauler Rightwise, while Rightwise’s lateral and terminal clamps moved slowly to fix Lindyin next to a canister of foodstuffs. She actually massed less than most of the constant-temp canisters Rightwisehad slung under her belly, less than the chemicals and the manufacturing components destined for station use.

She was in fact nothing but a shell with engines, an unlovely, jerry-rigged construction; and the Lukowskis, the Viking-based merchanter family which owned Rightwise, having only moderate larceny in their hearts and a genuine spacers’ sympathy for Lindy’s young owners, settled for the bonus Endeavor Station offered for the delivery of such ships and crews in lieu of Lindy’s freight, and took labor for the passage of the Murray-Gaineses themselves. Rightwisehad muscle to spare, and Lindy’s bonus would clear two percent above the mass charge: the owners were desperate.

So Rightwisechecked Lindy’s mass by Fargone records, double checked the dented, unshielded tanks that they were indeed empty for the haul, grappled her on and took her through jump to Endeavor—unlikely reprieve for that bit of scrap and spit which should long since have been sent to recycling.

AD 3/2⅗5

The Murrays and Paul Gaines arrived at Endeavor with the same hopes as the rest of the out-of-luck spacers incoming. Endeavor was a starstation in the process of building, sited in the current direction of Union expansion, in a rich (if unexportable) aggregation of ores. But trade would come, extending outward to new routes. Combines and companies would grow here. And the desperate and the ambitious flocked in. There were insystem haulers, freighted in on jumpships, among them a pair of moduled giant oreships, hauled in by half a dozen longhaulers in pieces, reassembled at Endeavor, of too great mass to have come in any other way. They were combine ships out of Viking, those two leviathans, and they collected the bulk of the advertised bonus for ships coming to Endeavor. There was a tanker from Cyteen; a freighter from Fargone, major ships—while most of the independent cold-haulers that labored the short station-belt run were far smaller, patched antiquities that gave Endeavor System the eerie ambiance of a hundred-year backstep in time. They were owned by their crews, those ancient craft, some family ships, most the association of non-kin who had gambled all their funds together on war surplus and ingenuity.

And smallest and least came ships like the Murray-Gaineses’ Lindy, an aged pusher-ship once designed for nothing more complex than boosting or slowing down a construction span or sweeping debris from Fargone Station’s peripheries, half a hundred years ago. They had blistered her small hull with longterm lifesupport. A human form jutted out of her portside like a decoration: an EVA-pod made of an old suit. Storage compartments bulged outward at odd angles almost as fanciful as the pod. Tanks were likewise jury-rigged on the ventral surface, and a skein of hazardously exposed conduits led to the war-salvage main engine and the chancy directionals.

No established station would have allowed Lindyregistry even before the alterations. She had been scheduled for junk at Fargone, and so had many of her parts, taken individually. But at Endeavor Lindywas no worse than others of her size. She was rigged for light prospecting in those several rings of ore-laden rock which belted Endeavor System, feeding the refiner-oreships, which would send their recovered materials in girder-form and bulk to Station, where belt ores and ice became structure, decks, machine parts and solar cells, fuel and oxygen. Lindywould haul only between belt and oreship, taking the richest small bits in her sling, tagging any larger finds for abler ships on a one-tenth split. She even had an advantage in her size: she could go gnat-like into stretches of the belt no larger ship would risk and, supplied by those larger ships, attach limpets to boost a worthwhile prize within reach: thatkind of risk was negotiable.

And if she broke down in Endeavor’s belt and killed her crew, well, that was the chance the Murray-Gaineses took, like all the rest who gambled on a future at Endeavor, on the hope of piling up credits in the station’s bank faster than they needed to consume them, credits and stock which would increase in worth as the station grew, which was how marginal operators like the Murray Gaineses hoped to get a lease on a safer ship and link into some forming Endeavor combine.

There was Endeavor Station: that was the first step. Rightwiselet go the clamps; the Murray-Gaineses sweated through the unpowered docking and the checkout, enjoyed one modest round of drinks at the cheapest of Endeavor Station’s four cheap bars, and opened their station account in Endeavor’s cubbyhole of a docking office, red-eyed and exhausted and anxious to pay off Rightwiseand get Lindyclear and away before they accumulated any additional dock charge.

So they applied for their papers and local number, paid their freight and registered their ship forthwith with hardly more formality than a clerical stamp, because Lindywas so ridiculously small there was no question of illicit weaponry or criminal record. She became STARSTATION ENDEAVOR INSYSTEM SHIP 243 Lindy, attached to SSEIS 1, the oreship/smelter Ajax. She had a home.

And the Murrays and Paul Gaines, free and clear of debt, went off arm in arm to Lindy’s obscure berth just under the maindawn limit which would have logged them a second day’s dock charge. They boarded and settled into that cramped interior, ran their checks of the charging that the station had done in their absence, and put her out under her own power without further ado, headed for Endeavor’s belt.

For a little while they had an aftward single G, in the acceleration which boosted them to their passage velocity; but after that small push they went inertial and null, in which condition they would live and work three to six months at a stretch.

They had bought three bottles of Downer wine for their stores. Those were for their first tour’s completion. They expected success. They were high on the anticipation of it. Rafe Murray, his sister Jillan, merchanter brats; Paul Gaines, of Fargone’s deep-miners, unlikely friendship, war-flotsam that they were. But there was no doubt in them, no division, when playmates had grown up and married: and Rafe was well content. “It’s tight quarters,” Jillan had said to her brother when they talked about Endeavor and their partnership. “It’s a long time out there, Rafe; it’s going to be real long; and real lonely.”

Paul Gaines had said much the same, in the way Paul could, because he and Rafe were close as brothers. “So, well,” Rafe had answered, “I’ll turn my back.”

They called Rafe, half-joking, half-not, their Old Man, at twenty-two. That meant captain, on a larger ship. And they werehis. Jillan planned on children in a merchanter-woman’s way. They were life, and she could get them, with any man; but, un-merchanter-like, she married Paul, for good, for permanent, not to lose him, and snared him in their dream. Their children would be Murrays; would grow up to the Name that the War had robbed of a ship and almost killed out entire ... and he dreamed with desperate fervor, did Rafe Murray, of holding Murray offspring in his arms, of a ship filled with youngsters—being himself a merchanter-man and incapable of pregnancy, which was how, after all, children got on ships: merchanter-women made them, and merchanter-women got his and took them to other ships which did not need them half so desperately.

He had had his partnerings with the women of Rightwiseand bade all that good-bye—”Go sleepover,” Paul had advised him on Endeavor dock. “Do you good.”

“Money,” he had said, meaning they could not spare the cost of a room, or the time. “Had my time on Rightwise. That’s enough. I’m tired.”

Paul had just looked at him, with pity in his eyes.

“What do you want?” he had answered then. “Had it last night. Three Rightwisers. Wore me out.” And Jillan walked up just then, so there was no more argument.

“We’ll have a ship,” Rafe had sworn to Jillan once, when they were nine and eight., and their mother and their uncle died, last of old freighter Lindy’s crew, both at once, in Fargone’s belt. Getting to deep space again had been theirdream; it was all the legacy they left, except a pair of silver crew-pins and a Name without a ship.

So Rafe held Jillan by him– Don’t leave me, don’t go stationer on me. You take your men; give me kids—give me that, and I’ll give you—all I’ve got, all I’ll ever have.

Don’t you leave me, Jillan had said back, equally dogged. You be the Old Man, that’s what you’ll be. Don’t you leave me and go forget your name. Don’t you do that, ever.And she worked with him and sweated and lived poor to bank every credit that came their way.

Most, she got him Paul Gaines, lured a miner-orphan to work with them, to risk his neck, to throw his money into it, Paul’s station-share, every credit they three could gain by work from scrubbing deck to serving hire-on crew to miners when they could get a berth.

Having children waited. Waited for the ship.

And Endeavor and a dilapidated pusher-ship were the purchase of all they had.

Rafe took first watch. He caught a reflection on the leftmost screen of Jillan and Paul in their sleeping web behind his chair, fallen asleep despite their attempt to keep him company, singing and joking. They had been quite a handful of minutes and there they drifted, collapsed together, like times the three of them had hidden to sleep, three kids on Fargone, making a ship out of a shipping canister, all tucked up in the dark and secret inside, dreaming they were exploring and that stars and infinity surrounded their little shell.

3/23/55

Mass.

<> came fully alert, feeling that certain tug at <>’s substance which meant something large disturbing the continuum.

Trishanamarandu-keptacould have overjumped the hazard, of course, adjusting course in mid-jump with the facility of vast power and a sentience which treated the mindcrippling between of jumps like some strange ocean which <> swam with native skill. But curiosity was the rule of < >’s existence. < > skipped down,if such a term had relevance, an insouciant hairbreadth from disaster.

It was a bit of debris, a lump of congealed material which to the questing eye of Trishanamarandu-keptaappeared as a blackness, a disruption, a point of great mass.

It was a failed star, an overambitious planet, a wanderer in the wide dark which had given up almost all its heat to the void and meant nothing any longer but a pockmark in spacetime.

It was a bit of the history of this region, telling <> something of the formational past. It was nothing remarkable in itself. The remarkable time for it had long since passed, the violent death of some far greater star hereabouts. Thatwould have been a sight.

<> journeyed, pursuing that thread of thought with some pleasure, charted the point of mass in <>’s indelible memory in the process.

The inevitable babble of curiosity had begun among the passengers. < >’s wakings were of interest to them. < > answered them curtly and leaped out into the deep again, heading simply to the next star, as < > did, having both eternity andjump capacity at < >’s disposal.

There was no hurry. There was nowhere in particular to go; and everywhere, of course. <> was now awake, lazily considering galactic motion and the likely center of that ancient supernova.

Such star-deaths begat descendants.

II

10/2/55

The Downer wine was opened, nullstopped and passed hand to hand in celebration. Music poured from Lindy’s comsystem. There was food in the freezer, water in the tanks, and a start to the fortunes of the Murray-Gaineses, a respectable number of credits logged on the orehauler Ajax, from what they had delivered and a share of what others had brought in with their beeper tags. They were bathed, shaved and fresh-scented from a docking and sleepover on Ajax. Even Lindyherself had a mint-new antiseptic tang to her air from the purging she had gotten during the hours of her stay.

“None of them,” Jillan said, drifting free, “none of them believed we could have come in filled that fast. No savvy at all, these so-named miners.”

“Baths,” Paul Gaines murmured, and took the wine in both hands for his turn, smug bliss on his square face when he had drunk. “We’re civilized again.”

“Drink to that,” Rafe agreed. “Here’s to the next load. How long’s it going to take us?”

“Under two months,” Jillan proposed. “Thirty tags and a full sling.”

“We can do it.” Rafe was extravagant. He felt a surge of warmth, thinking on an Ajaxwoman who had opened her cabin to him in his onship time. He was feeling at ease with everything and everyone. He gave a quirk of a smile at Jillan and Paul, whose privacy was one of the storage pods when they were down on supplies, but they were full stocked now, with solid credit to their account, stock bought in Endeavor itself. “Someday,” he said, “when we’re very old we can tell this to our kids and they won’t believe it.”

“Drink to someday,” Paul said, hugging Jillan with one arm, the bottle in the other. The motion started a drift and spin. Rafe snagged the bottle from Paul’s hand as they passed, laughing at them as the hug became a tumble, the two of them lost in each other and not needing that bottle in the least.

I love them,Rafe thought with an unaccustomed pang, with tears in his eyes he had no shame for. His sister and his best friend. His whole life was neatly knitted up together; and maybe next year they could build old Lindya little larger. Jillan could look to family-getting then, lie up on Ajaxfor the first baby; be with them thereafter—close quarters, but merchanter youngsters learned touch and not-touch, scramble and take-hold before they were steady on their feet.

And even for himself—for his own comfort—Endeavor was a haven for the orphaned, the displaced of the War, people like themselves, taking a last-ditch chance. There might be some woman someday, somehow, willing to take the kind of risk they posed.

Someone rare, like Paul.

“Drink up,” Jillan insisted, drifting down with Paul. The embrace opened ... a little frown had crossed Jillan’s face at the sight of his; and Paul’s expression mirrored the same concern. For that, for a thousand, thousand things, he loved them.

He grinned, and drank, and sent their bottle their way.

10/9/55

Trishanamarandu-keptawas in pursuit of delicate reckonings, had chased plottings round and round and busily gathered data in observation of the region. <> might have missed the ship entirely otherwise.

<> detected it in the Between, a meeting of which the ship might or might not be aware. It was small and slow, a bare ripple of presence.

It too was a consequence of that ancient stardeath ... or came here because of it. Weak as it seemed, it might well use mass like that which <> had recently visited as an anchor, a navigation fix when the distance between stars was too great for it. <> diverted <>’s self from <>’s previous heading and followed the ship, eager and intent, coming downat another such pockmark in the continuum, where <>’s small quarry had surfaced and paused.

(!), <> sent at once, in pulses along the whole range of <>’s transmitters. (!!!) (!!!!!)It was an ancient pattern, useful where there was no possibility of linguistic similarity and no reasonable guarantee of a similar range of perceptions. <> waited for response on any wavelength.

Waited.

Waited.

Even delays in response were informational. This might be recovery time, for senses severely disorganized by jumpspace. Some species were particularly affected by the experience. It might be slow consideration of the pulse message. The length of time to decide on reply, the manner of answer, whether echo or addition, whether linear or pyramidal ... species varied in their apprehension of the question.

The small ship remained some time at residual velocity, though headed toward the hazard of the dark mass by which it steered. Presumably it was aware of the danger of its course.

<> remained wary, having seen many variations on such meetings, some proceeding to sudden attack; some to approach; some to headlong flight; some even to suicide, which might be what was in progress as a result of that unchecked velocity.

Or possibly, remotely, the ship had suffered some malfunction. <> retained corresponding velocity and kept the same interval, confident in <>’s own agility and wondering whether the ship under observation could still escape.

<> observed, which was <>’s only present interest.

The little ship suddenly flicked out again into jump. <> followed, ignoring the babble from the passengers, which had been building and now broke into chaos.

Quiet,<> wished them all, afire with the passion of a new interest in existence.

The pursuit came downagain as <> had hoped, at a star teeming with activity on a broad range of wavelengths.

Life.

A whole spacefaring civilization.

It was like rain after ages-long drought; repletion after famine. <> stretched, enlivened capacities dormant for centuries, power like a great silent shout going through <>’s body.

Withdraw,some of the passengers wished <>. You’ll get us all killed.

There was humor in that. <> laughed. <> could, after <>’s fashion.

Attack,others raved, that being their natures.

Hush,<> said. Just watch.

We trusted you,<^> mourned.

<> ignored all the voices and stayed on course.

1/12/56

The intruder and its quarry went unnoticed for a time in Endeavor Station Central. Boards still showed clear. The trouble at the instant of its arrival was still a long, lightbound way out.

Ships closer to that arrival point picked up the situation and started relaying the signal as they moved in panic.

Three hours after arrival, Central longscan picked up a blip just above the ecliptic and beeped, routinely calling a human operator’s attention to that seldom active screen, which might register an arrival once or twice a month.

But not headed into central system plane, where no incoming ship belonged, vectored at jumpship velocities toward the precise area of the belt that was worked by Endeavor miners. Comp plotted a colored fan of possible courses, and someone swore, with feeling.

A second beep an instant later froze the several techs in their seats; and “Lord!”a scan tech breathed, because that second blip was closeto the first one.

“Check your pickup,” the supervisor said, walking near that station in the general murmur of dismay.

That had nearly been collision out there three lightbound hours ago. The odds against two unscheduled merchanters coinciding in Endeavor’s vast untrafficked space, illegally in system plane, were out of all reason.

“Tandem jump?” the tech wondered, pushing buttons to reset. Tandem jumping was a military maneuver. It required hairbreadth accuracy. No merchanter risked it as routine.

“Pirate,” a second tech surmised, which they were all thinking by now. There were still war troubles left, from the bad days. “Mazianni, maybe.”

The supervisor hesitated from one foot to the other, wiped his face. The stationmaster was offshift, asleep. It was hours into maindark. The supervisor was alterday chief, second highest on the station. The red-alert button was in front of him on the board, unused for all of Endeavor’s existence.

“... it’s behindus,” he heard next, the merchanter frequency, from out in the range. “Endeavor Station, do you read, do you read? This is merchanter John Lilesout of Viking. We’ve met a bogey out there ... it’s dragged us off mark ... Met ...”

Another signal was incoming. (!) (!!!) (!!!!!)

“... out there at Charlie Point,” the transmission from John Lileswent on. An echo had started, John Liles’ message relayed ship to ship from every prospector and orehauler in the system. Everyone’s ears were pricked. Bogeywas a nightmare word, a bad joke, a thing which happened to jumpspace pilots who were due for a long, long rest. But there weretwo images on scan, and a signal was incoming which made no sense. At that moment Endeavor Station seemed twice as far from the rest of mankind and twice as lonely as before.

“... It signaled us out there and we jumped on with no proper trank. Got sick kids aboard, people shaken up. We’re afraid to dump velocity; we may need what we’ve got. Station, get us help out here. It keeps signaling us. It’s solid. We got a vid image and it’s not one of ours, do you copy? Not one of ours or anybody’s.What are we supposed to do, Endeavor Station?”

Everywhere that message had reached, all along the time sequence of that incoming message, ships reacted, shorthaulers and orehaulers and prospectors changing course, exchanging a babble of intership communication as they aimed for eventual refuge out of the line of events. What interval incoming jumpships could cross in mere seconds, the insystem haulers plotted in days and weeks and months: they had no hope in speed, but in their turn-tail signal of noncombatancy.

In station central, the supervisor roused out the stationmaster by intercom. The thready voice from John Lileswent on and on, the speaker having tried to jam all the information he could into all the time he had, a little under three hours ago. Longscan techs in Endeavor Central were taking the hours-old course of the incoming vessels and making projections on the master screen, lines colored by degree of probability, along with reckonings of present position and courses of all the ships and objects everywhere in the system. Longscan was supposed to work because human logic and human body/human stress capacities were calculable, given original position, velocity, situation, ship class, and heading.

But one of those ships out there was another matter.

And John Lileswas not dumping velocity, was hurtling in toward the station on the tightest possible bend, the exact tightness of which had to do with how that ship was rigged inside, and what its capacity, load, and capabilities were. Computers were hunting such details frantically as longscan demanded data. The projections were cone-shaped flares of color, as yet unrefined. Com was ordering some small prospectors to head their ships nadir at once because they lay within those cones.

But those longscan projections suddenly revised themselves into a second hindcast, that those miners had started moving nadir on their own initiative the moment they picked up John Liles’ distress call the better part of three hours ago. Data began to confirm that hypothesis, communication coming in from SSEIS I Ajax, which was now a fraction nadir of original projection.

Lindyhad run early in those three hours, such as Lindycould ... dumped the sling and spent all she had, trying to gather velocity. Rafe plotted frantically, trying to hold a line which used the inertia they had and still would not take them into the collision hazard of the deep belt if they had to overspend. Jillan ran counterchecks on the figures and Paul was set at com, keeping a steady flow of John Liles’ transmission.

If Lindyoverspent and had nothing left for braking, if they survived the belt, there were three ships which might match them and snag them down before they passed out of the system and died adrift ... if they did not hit a rock their weak directionals could not avoid ... if the station itself survived what was coming in at them. They could all die here. Everyone. There were two military ships at Endeavor Station and Lindyhad no hope of help from them: the military’s priority in this situation was not to come after some minuscule dying miner, but to run, warning other stars so Paul said, who had served in Fargone militia, and they had no doubt of it. It was a question of priorities, and Lindywas no one’s priority but their own.

“How are we doing?” Rafe asked his sister, who had her eyes on other readouts. The curves were all but touching on the comp screen, one promising them collision, and one offering escape.

“Got a chance,” Jillan said, “if that merchanter gives us just a hair.”

Paul was transmitting, calmly, advising John Lilesthey were in its path. On the E-channel, Lindy’s, autowarning screamed collision alert: the wave of that message should have reached John Lilesby now.

“Rafe,” Jillan said, “recommend you take all the margin. Now.”

“Right.” Rafe asked no questions, having too much input from the boards to do anything but take it as he was told. He squeezed out the last safety margin they had before overspending, shut down on the mark, watching the computer replot the curves. In one ear, Paul was quietly, rationally advising John Lilesthat they were ten minutes from impact; in the other ear came the com flow from John Lilesitself, babble which still pleaded with station, wanting help, advising station that they were innocent of provocation toward the bogey. “Instruction,” John Lilesbegged again and again, ignoring communications from others. It was a tape playing. Possibly their medical emergency or their attention to the bogey behind them took all their wits.

“Come on,” Rafe muttered, flashing their docking floods in the distress code, into the diminishing interval of their light-speed message impacting the 3/4 C time-frame of John Liles’ Doppler receivers. He was not panicked. They were all too busy for panic. The calculations flashed tighter and tighter.

“We’ve got to destruct,” Paul said at last in a thin, strained voice. “Three of us—a thousand on that ship—O God, we’ve got to do it—”

Sudden static disrupted all their scan and com, blinding them. “She’s dumping,”Jillan yelled. John Lileshad cycled in the generation vanes, shedding velocity in pulses. They were getting the wash, like a storm passing, with a flaring of every alarm in the ship. It dissipated. “We’re all right,”Paul yelled prematurely. In the next instant scan cleared and showed them a vast shape coming dead on. Rafe froze, braced, frail human reaction against what impact was coming at them at a mind-bending 1/10 C.

It dumped speed again, another storm of blackout. Rafe moved, trembled in the wake of it, fired directionals to correct a yaw that had added itself to their motion. Scan cleared again.

“Clear that,” Rafe said. “Scan’s fouled.” The blip showed itself larger than Ajax, large as infant Endeavor Station itself.

“No,” Paul said. “Rafe, that’s not the merchanter.”

“Vid,” Rafe said. Paul was already flicking switches. The camera swept, a blur of stars, onscreen. It targeted, swung back, locked.

The ship in view was like nothing human-built, a disc cradled in a frame warted with bubbles of no sensible geometry, in massive extrusions on frame and disc like some bizarre cratering from within. The generation vanes, if that was what those projections were, stretched about it in a tangle of webbing as if some mad spider had been at work, veiling that toadish lump in gossamer. Lightnings flickered multicolor in the webs, and reflected off the warted body, a repeated sequence of pulses.