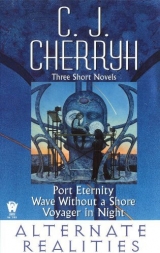

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

No one jumped a station-sized mass. By the laws he knew, nothing could, that did not conform to the conditions of a black hole. And it did it from virtual standstill.

He did not run when he had home in sight; he restrained himself, but his knees were shaking.

He sat down when he had gotten there, in the chair before the disjointed console, in the insane debris of Lindy’s corpse, and bowed his head onto his arms, because it ached.

Ached as if something were rent away from him.

He wiped his eyes and idly flipped a switch, jumped when a screen flared to life and gave him star-view.

He tried the controls, and there was nothing.

Com,he thought, and spun the chair about flipping switches, opening a channel, hoping it went somewhere. “Hello,” he said to it, to whatever was listening. “Hello—hello.”

“Aaaiiiiiiiiiieeeeeeee!”

“Damn.”he yelled back at it, reaction; and trembled after he had cut it off.

He went on, shaking, trying not to think at all, putting himself through insane routine of instrument checkout, as if he were still on Lindy’s bridge and not managing her pieces in this madness.

Com was connected to something—what, he had no wish to know. Vid gave him starfield, but he had no referent. The computer still worked, at least in areas the board had not lost. The lights still worked; one of the fans did, insanely; their tapes were still there, but the music would break his heart.

He slumped over finally and hid the sight of it from his eyes, suspecting worse ahead. It played games with him. He already knew that they were cruel.

IV

There was the dark, forever the void, and Rafe moved in it, calling sometimes—“Jillan, Paul—” but no one answered.

He should have been cold, he thought; but he had no more sense of the air about him than he had of the floor underfoot.

He turned in different directions, in which he found himself making slower and slower progress, as if he walked against a wind and then found himself facing (he thought) entirely a different direction than before.

“Aaaiiiiiiiiii!”something howled at him, went rushing past with a glow and a wail like nothing he had ever heard, and he scrambled back, braced for an attack.

It went away, just sped off insanely howling into the dark, and he sank down and crouched there in his nakedness, protecting himself in the only way he had, which was simply to hug his knees close and sit and tremble, totally blind except for the view of his own limbs.

“Jillan,” he whispered to the void, terrified of making any noise, any sound that would bring the howler back. His own gold-glowing flesh seemed all too conspicuous, beacon to any predator.

Android.He reminded himself what he was, that he could not be harmed; but his memories insisted he was Rafe Murray. It was all he knew how to be. And he knew now that they were not alone in this dark place.

At last he got himself to his feet and moved again, no longer sure in what direction he had been going, no longer sure but what the darkness concealed traps ahead, or that he was not being stalked behind.

“Jillan,” he called aloud. “Paul.”

Had that been one of the aliens—that passing, mindless wail, or some other victim fleeing God-knew-what ahead?

What is this place?

They were androids. That was what they were, what he had been when he had met his living body—met Rafe. Something had projected him into that green-noded corridor.

But then, he reasoned, Rafe ought to have been a projection sent in turn to him, and he had not been. Viewpoint troubled him, how he had seen through hologrammatic eyes. How that Rafe had thrust his hand into the heart of him and cursed him– Evaporate, why don’t you?

Why not?a small voice said. If I’m an android they can make me what they like. Can’t they?

Maybe they have.

Fake,that other Rafe had said, screaming at him his outrage at self-robbery.

That Rafe Murray had the scars, the bruises, the pain that proved his title to flesh and life.

Where are we? Where are Jillan and Paul? What will they do to us? What have they done already and what am I?

“Jillan,” he screamed with all his force. “Paul! Answer me! Answer me...” with the terror that he would never find them, that they had been taken away to some final disposition, and that it would take him soon, questions all unanswered.

Why did they make us?

He feared truths, that whoever had made him could throw some switch and bring him somewhere else, back where they had made him, back to that place with the machinery and the blood; perhaps would unmake him then. He feared death—that it was still possible for him.

“Aaaaaaaaaaauuuuu!”Another thing passed him, roaring like some machine out of control, and he stopped, stood trembling until it had faded into the distance.

“Stop playing games with me,” he said quietly, trusting of a sudden that something heard him better than it would hear that other, living Rafe. “Do you hear me? I’m not impressed.”

Could it speak any human tongue? Had it learned, was it learning now?

“Damn you,” he said conversationally, shrugged and kept walking, pretending indifference inside and out. But the cold that was not truly in the air had lodged beneath the heart. God,he appealed to the invisible—he was Catholic, at least the Murrays had always been; but God—God was for something that had the attributes of life.

Rafe One had God; he had Them. It. Whatever had made him. It might flip a switch, speak a word, reach into him and turn him inside out for a joke. That was power enough.

“Jillan!” he yelled, angry—He could still feel rage, proving—proving what? he wondered. The contradictions multiplied into howling panic. “Jillan!”

“Rafe?”

He turned, no more anywhere than before, in the all-encompassing dark. He saw a light coming to him, that wafted as if a wind blew it. It was Paul, and Jillan came running in his wake.

“Rafe,” Jillan cried, and met him and hugged him, warm, naked flesh that reminded him flesh existed here– synthetic?he remembered. Paul hugged him too; and his mind went hurtling back to that howling thing in the dark, remembering that here it would be palpable and true, He shivered in their arms.

“There are thingsin here,” Jillan said.

“I know, I know. I heard them,” he said, holding her, being held, until the shivers went away.

“Don’t go off from us again,” Paul said. “Dammit, Rafe, we could get lost in here.”

He broke into laughter, sobbed instead. He touched Jillan’s earnest, offended face and saw her fear. “Did you find what you were looking for?”

“Dark, “Jillan said. “Just dark. No way out.”

“I met someone,” he said to them, and let the words sink in, watching their faces as the sense of it got through. “I metsomeone.”

“Who?” Jillan asked, carefully, ever so carefully, as if she feared his mind had gone.

“Myself. The body that we saw. There in the corridor. He wants to talk to you.”

“You mean you went back,” said Paul.

“I talked to him.”

“Him?”

“Myself. He’s alive, you understand that? I met him—face to face. Jillan—” he said, for she began to turn to Paul. “Jillan—we’re not—not the real ones. They’ve made us. The memories, our bodies—We’re not real.”

There was devastated silence.

“If we could get back,” said Paul.

“It’s not a question of getting back,” Rafe said, catching at Paul’s arm. “Paul, we’re constructs.”

“You’re out of your mind.”

Rafe laughed, a sickly, sorrowful mirth. “Yes,” he said. “Out of his. The way you came out of Paul’s; and Jillan’s out of her. Constructs, hear? Androids. Robots. Our senses—aren’t reliable. We got only what the ones who made us want. God knows where we really are.”

“Stop, it!” Jillan cried, shaking at his arms. “Rafe, stop it, you hear me?”

He seized her and hugged her close, felt her trembling—Could an android grieve? But it was Jillan’s grief, Jillan’s terror. His sister’s. Paul’s. It was unbearable, this pain; and like the other it did not look to stop.

“Rafe,” Paul said, and pulling him away into his arms, pressed his head against his shoulder and tried to soothe him as if he had gone stark mad. There was the smell of their flesh, cool and human in this sterility; the touch of their hands; the texture of their hair—Real, his senses told him. Someone was playing with their minds; that was the answer. That’s why Rafe’s solid to me and I’m not that way to him.

“Please,” he said, pushing away from them. “Come with me. Let me take you to him. Talk with him.”

“We’ve got to get out of here.” Jillan’s eyes had all space and void in their depths. “Rafe, pull yourself together. Don’t go off like this. They’re tricks. They’re all just tricks. They’re working on our minds, that’s what’s happening. That’s why none of this makes sense.”

“Get out of it, how, Jillan? We came through jump. Lindy’s in pieces, back there in that hall.”

“It’s illusion. They want us to think it is. They’re lying, you understand?”

“Jump wasn’t a lie.”

“We’ve got to do something to get out of here.”

“Jillan—” He wanted to believe her. He wanted it with all his mind. But he suspected a dreadful thing, staring into her eyes. He suspected a whole spectrum of dreadful truths, and did not know how to tell her. “Jillan,” he said as gently as he could. “Jillan, he wants to talk to you and Paul, he wants it very much.”

“There is no he!” Paul shouted.

“Then come with me and prove it.”

“There’s no proving it. There’s no proving anything about an illusion, except you put your hand into it and it isn’t there.”

“He did that to me. Put his hand through me. I wasn’t there.”

“You’re talking crazy,” Paul said.

“All you have to do is come with me. Talk to him.”

“It’s one of them. That’s what it is.”

“Maybe it is,” Rafe said. He felt cold, as if a wind had blown over his soul. “But prove it to me. I’ll do anything you want if you can prove it to me. Come and make me believe it. I want to believe you’re right.”

“Rafe,” Jillan said.

“Come with me,” he said, and when they seemed disposed to refuse: “Where else can we find anything out for sure?”

“All right,” Jillan said, though Paul muttered otherwise. “All right. I’m coming. Come on, Paul.”

She took his hand. Paul came up on his other side. He turned back the way he had come, as near he could remember, walking with two-meter strides, not knowing even if he could find that place again. But the moment he started to move it began to be about him again, the light, the noded, green-gossamer corridor, Lindy’s wreckage like flotsam on a reef.

And the other Rafe, the living one, sat on the floor against the wall. That Rafe looked up in startlement and scrambled stiffly to his feet, wincing with the pain.

“Rafe,” Rafe said, for it had been a long and lonely time, how long he did not know, only he had had time to meddle uselessly with the console, to shave and wash, and sleep. And now the doppelganger was back, in the shadows where his image showed best, naked as before.

And on either side of him arrived Jillan and Paul, naked, pitiful in their fear.

At least their images—whose eyes rested on him in horror, and warned him by that of their fragility. He could not hurt them. His own doppelganger—that was himself, but Jillan and Paul drove a wedge into his heart. “He found you,” he said to them, patient of cruel illusion, of anything that gave him their likenesses, even if it mocked him in the gift.

“What areyou?” Jillan said, driving the dagger deeper. There was panic in her voice.

“Don’t be afraid,” Rafe said. But Paul went out– out, like the extinguishing of a light, and Jillan backed away, shaking her head at his offered hand.

“No,” she said. “No.” And fled, raced ghostlike through the wall.

His own doppelganger still stood there, naked, hands empty at his sides, with anguish in his eyes.

“I tried,” the doppelganger said with a motion of his hand. “I tried. Rafe—they’ll come back. Sooner or later they’ll have to come back. There’s nowhere else to go.”

Rafe sank down where he stood, where a node made a sitting-place against the wall. He ached in every bone and muscle, and looked up at the doppelganger in unadulterated misery.

“Rafe,” the doppelganger said. “I think they’re dead. You understand me? They haven’t found anything of themselves. I’m not sure there’s anything left to find.”

Rafe shut his eyes, willing it all away; but the doppelganger had come closer when he opened them. It knelt in front of him, waiting, his own face projecting grief and sympathy back at him.

“You understand?” the doppelganger said. “They’re copies. That’s all I found. They’re like me.”

He wanted to scream at it to go away, to be silent, but a strange self-courtesy held him still to listen, to sit calmly with his hands on his knees and stare into his own face, knowing the doppelganger’s pain, knowing it to the height and depth, what it cost and how it hurt. Jillan dead. And Paul.He had known it in his heart for hours, that this place, this graveyard caricature of Lindyhad all the important pieces in it. The console. The EVAPOD. Himself. All the working salvage that was left. “Do they know?” he asked, half insane himself.

“I can’t tell.” The image remained kneeling there. “On the one hand they could be right; they thought—they thought this was illusion. Maybe it is. But it was too strong a one for them.”

“It’s not illusion.”

“I don’t think so either.”

“God, this is mad!”

“I know. I know it is. But I think you’re right. We split—I remember all this pain. I remember—these arms waving about. It hurt, I never remember any pain like that—”

“Cut it out.!”

“I think—that was where they died.”

“Shut up!”

That Rafe tucked up his knees, rested his forehead on his arms—grief incarnate, mirror of his own, mirror until it hurt to look at himself, knowing what he felt, seeing it mimed in front of him. Rafe Two lifted his head at last, stared at him with ineffable bleakness, and he began to shiver himself in long slow tremors.

“Cry,” the soft voice came to him. “I did, awhile, for what it’s worth. I cried a lot. But it can’t change what is. Don’t you think I want to believe you’re not real? That we’re all of us all right? I wish I could believe that. You wish you could get rid of me. But you can’t. And we aren’t.”

“Damn you!” He leaped up, ran to the console, seized on the first thing he could find and flung it at the doppelganger. It was one of his music tapes, which passed through the image and hit the wall, falling harmless as the curse; and the doppelganger just sat there, breathing, doing everything it should not. Its breath came hard, one long heave of its naked shoulders, its head bowed as if it fought for self-control. It mastered itself, better than he; or having fewer options. It was resignation that looked back at him with his own face, out of bruised and weary eyes, and he could not bear that defeat. He sank down at the console and gasped for air that seemed too thin, with thoughts that seemed too rarified to hold without suffocating. Things swirled about him: Dead, dead, dead—

Die too, why can’t you?

He did not cry. Sitting there, he shivered until his muscles ached and cramped, until lack of air brought him to bow his head on the console.

“He’s real,” he heard his own voice say; and Jillan’s then: “No,” so that he opened his eyes and found them standing there, all of them, his dead, his living self—

“O God,” he said, “God, Jillan, Paul—don’t go, don’t go this time.” He levered himself up, unsteady on his feet, offered them his hand, even knowing they could not touch it. “Stay here. Don’t run.”

His doppelganger walked to him, stood close by him, ghostly thin, standing where he stood in parodied embrace. There was no sensation from it, only a confusion of image, as if it had superimposed itself deliberately.

“Don’t go,” it echoed him. “Don’t you see—we’re the illusion. Projected here. We’re androids. That’s all we are. Made out of him, his mind, Jillan’s, Paul’s. We’re the shadows. He’s the real one.”

They stood there, the two of them, staring at him. “It doesn’t make sense,” Jillan said in a small voice. “Rafe—we can’t be dead. Can we?”

Rafe himself sank down to his knees on the gossamer-covered carpet, squeezed his eyes shut and shook his head to clear it of all the accumulated lunacy.

“I think,” said the other Rafe, standing over him, about him, a moving pale shimmer—”I think it’s very likely, if we can’t find the bodies. I think you are.”

“Then what are we?” Paul yelled.

“Androids,” said Rafe Two. “Something like that, at least. They made us. And the originals are gone.” He walked over near the console, touched the edges of the seats with insubstantial fingers. “We never rigged Lindyfor much stress.”

“Something that they made,” Jillan said. “is that what you’re saying?”

“Yes,” Rafe said, himself, looking up at her from where he knelt. She was still in every particular his sister, that look, that quiet steady sense. It shattered him. “Yes. Something that they made.”

She stared in his direction a moment, then shrugged and laughed, taking a step away. “I don’t feeldead.” A second step, so that she began to fade out at the wall. “I’m going out of focus, aren’t I?” Soberly, with horror beneath the surface. “It’s a pretty good copy. Aren’t I?”

“Stop it!” Paul said.

“Jillan’s right,” Rafe Two said, by the EVApod. “It was the seats, understand? We never rigged for more than two or three G at most. We got a lot more than that. It flung us off. Remember? Autopilot went crazy. My fault, maybe. But I couldn’t stop us. Nothing could, our tanks depleted—Couldn’t if we’d had Lindyat max. Lindycouldn’t cope with it.”

“We’re not dead,” Paul said.

“Whatever we are,” Rafe Two said, folding his insubstantial arms, “I guess we don’t have that problem. Not anymore we don’t.”

“We aren’t dead!”

“Let be,” Rafe said, hating his own tendencies to push a thing. Paul hated to be pushed.

“We’re us-prime,” Jillan said. “That’s what we are.” She came and squatted near him, looking at him closely for the first time, her hands clasped together on her knees, her knees drawn up. “I wish you could lend me a blanket, brother.”

“I wish I could,” he said. “Are you cold?” That she should be cold seemed to him the last, unbearably cruelty.

She shook her head. “Just the indignity of the thing. I tell you, when we meet what did this to us, when we meet them, I’ll sure insist on my clothes back.”

“I’ll insist on more than that,” he said.

“You’ve already met it!” Paul shouted, over by the wall. “ That’sRafe—the one like us! Ask it where we are. Ask it what kind of jokes it likes to play, what it’s up to, where it came from, what it wants from us!”

“I’m alive,” Rafe said.

“He’s the one that bleeds,” said his doppelganger, from close by. “Look at his face. He’s the one that survived the wreck. Not a mark on any of the rest of us—is there?” Rafe Two squatted down nearby, elbows on his knees. “At least,” he said to Jillan’s wraith, “you’ve got title to a name. Rafe and I—we aren’t the same anymore, not quite. We split. He’s been alone and I’ve been chasing you, and on that reckoning we get less and less in step, while you—you arehis sister, much as mine; you took up where the other left off—permanently. And so did you, Paul. That’s why it seems to you you’re still alive. But I can tell myself apart from him. I’m Rafe who found that one lying unconscious on the floor; and he’s the one who met himself face to face awake. Different perspectives. Dead’s meaningless to you. You’re not that Jillan Murray; you’re her hypothesis, you’re what she would have done—being met with that place where we woke up. You’re not that Paul Gaines. You’re just living your present on his memories—the way I split off from his, and did things different than he did.”

Paul came slowly away from the wall, stood there and shook his head. “I won’t give in to this. You’re wrong.”

“At least,” Rafe said, “sit down. Sit down. Please.”

“It’s dark out there,” said Paul, as if it were a matter of petulant complaint.

“Rafe said,” Rafe answered him. “Stay here. Please.”

Paul came and joined them, farthest away, crouched on the floor and plucked disinterestedly at a shred of gossamer he failed even to touch.

“We’re interested in the same things, aren’t we?” Rafe said. “We’re still partners. We need to find out where we are. And I love you,” he added, because it was so, and he had not said it often enough. He remembered what he was talking to, but it was as close as he could come. “I do love you two. ...”—To convince himself, he thought.

“I know,” Jillan said. Her eyes were dreadful, as if they saw too much. “I know that, Rafe.”

“Nothing for me,” said Rafe Two, who sat by him mirrorlike, arms about naked knees. “You see what it is to be surplus? Better to be dead. At least there’s appreciation.”

“Shut it up,” Rafe said. “I always had a bad sense of timing. I won’t put up with it from you.”

“Stop it!”Paul said.

“It’s like being schizophrenic,” Rafe said, looking at the floor, pulling with his fingers at another loose bit of gossamer that refused to tear. “It’s really strong, this stuff.”

“What are we going to do?” Jillan asked.

“I don’t see any profit in sitting still,” Paul said. “Do you?”

“What do you suggest? It—they—whatever—whatever, runs this place knows where weare. When it gets bored, it’ll find us.”

Paul glared at him.

“I don’t want to sit here,” Jillan said.

“There’s the corridors,” said Rafe Two. “We could try to go as far as we can. As far as we can stay with each other.”

“We could try that,” Rafe said.

The outsiders moved slowly down the corridor which had been allotted to them and there was, immediately, throughout the ship, a focusing, of attention.

“They’re a hazard,” [] said. [] had tried them once, but <> had interfered in no uncertain terms and [] kept respectful distance.

“Let them go,” said <^>. <^> was constantly disposed to gentleness. It was part of <^>’s madness, forgetting <^>’s heredity.

But ranged all about the perimeters, gathering others of ’s disposition: there were many such aboard. There were two or three fiercer, but none more devious, except maybe the segments of = <-> = = <+> = that grew longer with every cannibalistic acquisition. = <-> = = <+> lg = had fifteen other segments, currently at liberty, and it was a question where these were or what the whole matrix thought, breaking apart and sending segments of itself everywhere in search of information.

laughed to self, loving chaos, seeing opportunity.

Trishanamarandu-keptadevoted only a part of <> ’s mind to this maneuvering. There were other things to occupy <>’s mind, a wealth of things the little ship had given up, records, names.

Of the simulacra themselves, three templates existed, which were deliberately dissociated in fragments.

From those templates <> integrated three temporary copies.

Rafe waked, aware of nakedness, of dark, of Paul and Jillan close beside him.

He wept, recalling pain, got to his knees and shook at Jillan’s bare shoulder. “Jillan,” he said.

The eyes opened, fixed. Jillan began to tremble, to convulse in spasms, to scream long tearing screams.

“Jillan!” Rafe yelled, trying to hold her. Paul was awake too, trying to restrain her and evade her blows.

These were temporary copies, easily erased, and served as comparison against which <>’s own symbol systems could be examined.

<> tried one on. It proved difficult, and retreated into gibberish; <> shut it down.

There remained Rafe and Jillan. The one called Rafe seemed the easiest of entry. The most stable seemed Jillan, and <> shut Rafe-mind down for the moment, to consider Jillan’s, which bent and flexed and made defensive mazes of its workings—giving way quickly and then proving vastly resilient.

“Rafe,” Jillan cried as they waked together in this dark place, and Rafe stared at her, leaning backward on his arms, seeming unable to do more than shiver. “There was—” he said, started to say, and cried out and fell back.

“Rafe!” she cried, and shook at him, but he was loose as if someone had broken him, and then he went away, just vanished, as if he had never been.

“Rafe!”she screamed at the vacant air, at the ceiling, and the dark. “Paul!”She scrambled up and threatened the invisible with empty hands and great violence.

It would fight, this Jillan-mind. <> learned that. The passengers who hovered near to witness this were profoundly disturbed.

“<> is taking risks again,” whispered in far recesses of the ship. “One day <> will miscalculate. Remember = = = = before = = = = turned cannibal? <> did not foresee that either.”

<> ignored these whispers, being occupied with <>’s insertion into the Jillan-mind.

Who are you?Jillan-mind asked <>. She wept; she fought the intrusions and when she no longer could do that she took in the flood with the peculiar strength she had and started trying to bend it to her shape.

She looked at , which had come to hover near, and bent <>’s thoughts to notice the observer in the dark.

“I don’t trust that one,” she declared, and <> laughed for startlement, in the rest of <>’s mind, which went on seeing things from outside, and managing <>’s body, and doing the other things <> did in the normal course of <>’s existence.

Then <> moved in Jillan-mind abruptly and without gentleness. <> brushed aside defenses and began to take what <> wanted. Jillan screamed at <> in anger and in pain and finally, because <> filled all the pathways of her mind at once and ran out of storage, the scream changed character and reason.

<> meddled with this state for a moment, adjusting this, tampering with that. <> had known already that the storage was not adequate and now <> formed strategies, knowing the dimensions of what <> had. The pain went on, while <> probed connections and relationships.

Jillan stabilized again, regarded the dark and welcomed it with fierce enthusiasm and hunger.

<> erased her then abruptly, for she had gotten far from the template, and ceased to be instructive. Or safe. In any sense.

<> made a second, fresher copy. <> could do that endlessly, in possession of the templates <> had made.

<> began again, with a surer, more knowing touch.

“Is it worth it?” <*> asked, straying close. “Let this creature go.”

<> turned the Jillan-face toward <*>’s undisguised self and felt a jolt of horror and of sound.

“That was unkind,” <> said, and destroyed her yet again.

“You’ll have to wait,” Rafe said, in their trek through endless corridors of endless green-gossamer and lumpish contours. Nothing had changed. They discovered nothing but endless sameness. He sank down, resting his back against the wall, and shut his eyes—opened them again for fear of finding himself alone, but the images stayed with him. They had sat down as if they needed to, Rafe Two foremost, always closest to him. He heaved a breath, felt his bruised ribs creak, felt thirst and hunger. Tears leaked unwanted from his eyes, simple exhaustion, and horror at the sameness and the sight that kept staring back at him.

Ghosts. Solemn Rafe; Jillan being nonchalant; Paul glowering—they frightened him. He could not touch them. He could not hug them to him, ever again. He knew those looks—Paul’s when he had an idea and would not let it go, Jillan’s when she was on the edge, and tottering.

“Come on,” he said, “Jillan. Swear. Do something. Don’t be cheerful at me.”

Her face settled into something true and dour. She looked up at him, thinking—

–thinking what? he wondered. Seeing aliens behind his eyes? Or feeling her own death again?

“You all right?” he asked.

“Sure, sure I’m all right,” Jillan said, and looked about, redirecting what got uncomfortable. “Whatever designed this place was crazy, you know that?”

“Whatever keeps us here sure is,” Rafe Two said.

“It’s kept me alive,” Rafe answered the doppelganger. He wiped at his mouth, looked up and down the windings of the corridor—they had gone down this time, if the large chamber had been up. “That it leaves me alone, you know, is something encouraging.”

“There’s another place,” said Rafe Two. “It’s dark, and nothing, and if that’s its normal condition, that thing’s nothing like us at all.”

“It’s playing games,” Paul said; and Rafe looked at him with some little hope– it, then; Paul had stopped throwing that itat him, had perhaps reconceived his situation. “There’s no guarantee it has a logic, you figure that?”

“It’s got math; math’s logic,” Jillan said.

“A lunatic can add,” Paul said, gnawing at his lip. “I don’t get tired. You’re sweating and I don’t get tired.”

“Dead has advantages, it seems,” Rafe Two said.

“Shut up!”

“Try thinking,” Rafe said, shifting to thrust a leg between his doppelganger and Paul’s image. “Try thinking—how we go about talking to this thing. It tried to talk to us. Back there—at Endeavor, it made an approach. Maybe taking us was a mistake in the first place.”

“Come on,” said Jillan harshly. “It knew we were there, knew how small we were. We couldn’t support jump engines. It damn well knew.”

He blinked at his sister, felt the sweat running in his eyes, mortality that she was beyond feeling. “I’ll find a way to ask it,” he said. Of a sudden he wanted to cry, right there in front of them, as if the jolt had just gotten through to him, but all he managed was a little trickle from his eyes and a painful jerk of breath. “I’ll tell you this. If it turns out the way you think and you can’t get your hands on it, I’ll get it. I’ll go for it. You can believe I will.”

“I’ve thought of something else,” said Rafe Two.

“What’s that?”

“That offending it might turn us off. That it can do that anyway when it wants.”

“What he’s saying,” Jillan said, “is that it has us for hostages. And maybe it’s not being whimsical with us. Maybe it’s looking to learn—oh, basic things. Like how we build; what our logic’s like—”

“—from Lindy’s wire and bolts,” Rafe scoffed. “Lord, it’ll wonder how we got to space at all.”

“—our language; our little computer, simple as it is—”

“—how our minds work,” said Paul. “They’ll start prodding at us. They’ve kept us too—you figure that, Rafe? They’ve gone to a lot of trouble.”

“It still could be,” Rafe said, “what you might say ... humanitarian concern. Maybe they panicked and bolted and we were an unwanted attachment.”