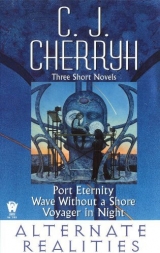

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

“Ourselves,” he said, and the course of it was all but finished except for the waving of the tubes that attached themselves—so, so sinister those thin lines, and the line that appeared leading in another section, and the arrival of another bit of debris far across the wheel ... something our last jump had swept in, I reckoned.

And Modred looked back at us then. “It’s shown us our way out,” he said. “We’ve got to open our forward hatch and go to it.”

“O dear God,” Dela said with a shake of the head.

“No,” Lynette said. “I don’t think that’s a thing to do that quickly.”

“You persist,” Modred said, “against the evidence.”

“Which can be read other ways,” Griffin said. “No.”

“Lady Dela,” Modred said. Patiently, stone-faced as ever, but his voice was hoarse. “It’s a question of profitability. Some of those ships on the ring didn’t change. At some points that intrusion failed. And others directly next to them changed. So some do drive it off. There’s the tubes, and separately—the wheel itself. It’s made an access out to the point where we touch the wheel. We’re very close to an oxygen section. Very close to where we should have docked. It can let us through where we have to go.”

“Has it occurred to anyone,” Vivien asked out of turn, “that however complicated—however attractive and rational and difficult the logical jump it’s put us through to reach it—that the thing might lie?”

A chill went through me. We looked at one another and for a moment no one had anything to say.

“It’s a born-man,” Percy said in his soft voice. “Or creature. And so it might lie.”

I felt myself paralyzed. And Modred stood there for a moment with a confusion in his eyes, because he was never set up to understand such things—lies, and structures of untruth.

Then he turned and walked toward the main board, just a natural kind of movement, but suddenly everyone seemed to think of it and the crew grabbed for him as Lance and Griffin moved all in the same moment

Modred lunged, too near to be stopped: his hand hit a control and there was a sound of hydraulics forward before Lance reached past Gawain and Percy and Lynn who pinned Modred to the counter. Lance hauled Modred out and swung him about and hit him hard before Griffin could hinder his arm. Modred hit the floor and slid over under the edge of Gawain’s vacant seat, lying sprawled and limp, but Lance would have gone after him, if not for Griffin—And meanwhile Lynette was working frantically at the board, but there had not been a sound of the hydraulics working again.

Our lock was open. Modred had opened us up. The realization got through to Dela and she flew across the deck to Griffin and Lance and the rest of them. “Close it—for God’s sake, close it,” Dela cried, and I just stood there with my hands to my mouth because it was clear it was not happening.

“It’s not working,” Lynn said. “Lady Dela, there’s something in the doorway and the safety’s on—”

“Override,” Griffin said.

“There might be some onein the way—”

“Override.”

Lynn jabbed the button; and all my nerves flinched from the sound that should have come, maybe cutting some living thing in half—But it failed.

“They’ve got it braced wide open,” Gawain said. “Percy—get cameras down there—”

Percy swung about, and reached the keyboard. All of a sudden we had picture and sound, this hideous babble, this conglomeration of serpent bodies in clear focus—serpents and other things as unlovely, a heaving mass within the Maid’s airlock. The second door still held firm, and there was our barrier beyond—there was still that.

“We’ve got to get down there,” Griffin said.

“They can’t get through so quickly,” Dela said. Her teeth were chattering.

“They don’t have to be delicate now they’ve got that outer lock braced open.” Griffin was distraught, his hands on Dela’s shoulders. He looked around at all of us. “Suit up. Now. We don’t know what they may do. Dela, get to the dining hall and just stay there. And get him out of here—” The latter for Modred, who lay unmoving. “Get him out, locked up, out of our way.”

Lance bent down and dragged Modred up. I started to help, took Modred’s arm, which was totally limp, as if that great blow had broken him—as if all the fire and drive had just burned him out and Lance’s blow had shattered him. For that moment I pitied him, for he never meant to betray us, but he was Modred, made that way and named for it. “Let me,” Percivale said, who was much stronger, and who would treat him gently. So I surrendered him to Percivale, to take away, to lock up where he could do us no more harm.

“He’d fight for us,” I said to Griffin, thinking that we could hardly spare Modred’s wit and his strength, whatever there was left to do now.

“We can’t rely on that,” Griffin said. He laid his hand on my shoulder, with Dela right there in his other arm. “Elaine—all of you. We do what we planned. All right?”

“Yes, sir,” I said, and Gawain the same. A silence from Vivien.

“Come on,” Griffin said.

So we went, and now over com we could hear the sound of what had gotten into the ship. I imagined them calling for cutters in their hisses and their squeals, and scaly dragon bodies pressing forward—oh, it could happen quickly now, and my skin drew as if there had been a cold wind blowing.

No sound of trumpets. No brave charge. We had armor, but it was all too fragile, and swords, but they had lasers, all too likely; and all the history of this place was theirs, not ours.

XV

A land of old upheaven from the abyss

By fire, to sink into the abyss again;

Where fragments of forgotten peoples dwelt,

And the long mountains ended in a coast

Of ever-shifting sand, and far away

The phantom circle of a moaning sea.

... And there, that day when the great light of heaven

Burned at his lowest in the rolling year,

On the waste sand by the waste sea they closed.

Nor yet had Arthur fought a fight

Like this last, dim, weird battle of the west.

A deathwhite mist slept over sand and sea:

Whereof the chill, to him who breathed it, drew

Down with his blood, till all his heart was cold

With formless fear; and ev’n on Arthur fell

Confusion, since he saw not whom he fought.

For friend and foe were shadows in the mist,

And friend slew friend not knowing whom he slew.

We had put the suits all in the dining room, all piled in the corner like so many bodies; and the breathing units were by them in a stack; and the helmets by those.... “Shouldn’t we,” I said, taking my lady’s suit from Percy, who was distributing pieces. I turned to my lady. “—shouldn’t we take Modred’s to him—in case?”

“No,” Griffin said behind me, and firmly. “He’ll be safe enough only so he stays put.”

I doubted that. I doubted it for all of us, and it seemed cruel to me. But I helped my lady with her suit, which she had never put on before, and which I had never tried. Lance was helping Griffin with his; but Lynn and Gawain had to intervene with both of us to help because they knew the fittings and where things should go and we did not.

Griffin was first done, knowing himself something about suits and getting into them. He had his helmet in his hand and waved off assistance from Gawain. “Dela,” he said then, “you stay here. You can’t help down there, you hear me?”

“I hear you,” she said, “but I’m coming down there anyway.”

“Dela—”

“I’ll stay back,” she said, “but I’ll be behind you.”

Griffin looked distraught. He wanted to say no again, that was sure; but he turned then and took one of the swords in hand, his helmet tucked under his arm. “There’ll be no using the beam cutters or the explosives,” he said. “If that’s methane out there. Modred did us that much service. So the swords and spears are all we’ve got. Dela—” Maybe he had something more to say and changed his mind. He lost it, whatever it had been, and walked off and out the door while we worked frantically at my lady’s fastenings.

“Hurry,” Dela insisted, and Lynette got the last clip fastened.

“Done,” Lynn said, and my lady, moving carefully in the weight, took her helmet from my hands and tucked that up, then gathered up several of the spears.

“Vivien,” my lady said sharply, and fixed Viv with her eye, because Viv was standing against the wall with never a move to do anything. “You want to wait here until they come slithering up the halls, Vivien?”

“No, lady,” Vivien said, and went and took the suit that Percy offered her.

“Help me,” Viv said to us. She meant it as an order. But my lady was already headed out the door, and Lance and I were in no frame of mind to wait on Vivien.

“Get us ready,” I said to Lynn and Gawain. “Hurry. Hurry. They’re alone down there.”

But Percivale delayed his own suiting to attend to Vivien, who was all but shivering with fright. I heard the lift work a second time and knew my lady had gone without us ... and still we had that sound everywhere. Lynn batted my overanxious hands from the fastenings and did them the way they should be done, and settled the weight of the lifesupport on me so that I felt my knees buckle; and fastened that with snaps of catches. “Go,” she said then, and I bent gingerly to get my helmet and took another several of the spears. But Lance took a sword the same as Griffin’s, and a spear besides. He moved as if that great weight of the suit were nothing to him. He strode out and down the corridor, and I followed after him as best I could, panting and trying not to catch a spearpoint on the lighting fixtures of the walls.

I had no intention that he should wait; if he could get to the lift and get down there the faster, so much the better, but he held the lift for me and shouted at me to hurry, so I came, with the shuffling haste I could manage, and I got myself and my unwieldly load into the lift and leaned against the wall as he hit the button with his gloved knuckles. It dropped us down that two deck distance and the door opened on a hideous din of thumps and bangs, but remoter than I had feared.

My lady was there, and Griffin. They stood hand in hand in front of the welded barrier, their weapons set aside, and they looked glad to see us as we came.

“Elaine,” Griffin said right off, “your job is to protect your lady, you understand. You stay beside her whatever happens.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“And Lance,” he said, “I need you.”

“Yes, sir,” Lance said without quibble, because it meant being up front beyond a doubt, with all our hopes in defense of all of us.

“They’re not through the airlock yet,” Dela said. “They’re working at it.”

“When our atmospheres mix,” Griffin said, “we’re in danger of blowing everything. At least they know. I imagine they’ll use some kind of a pressure gate and do the cut in an oxygen mix. If they’ve got suits, and I’m betting they do.”

“We could set up a defense on next level,” Lance said.

“Same danger there; they convert this level to their own atmosphere, then we’ve got it all over again. Our whole lifesupport bled out into all that methane would diffuse too much for any danger; but if they let all that methane in here—it could blow the ship apart. A quick way out. There’s that. We could always touch it off ourselves.”

“Griffin,” Dela said.

“If we had to.”

I felt cold, that was all, cold all the way inside, despite that carrying the suit made me sweat.

The lift worked. Vivien came, alone, walking with difficulty, and she had gotten herself one of the spears, carrying that in one hand, and her helmet under the other arm. She joined us.

And the lift went up and came down again with Gawain and Lynn and Percy, who moved better with their suits than the rest of us. They had swords and spears, and some of the knives with them.

“We wait,” Griffin said.

So we got down on our knees, that being the only way to sit down in the suits, and I only hoped we should have a great deal of warning, when the attack came, because even the strongest of us were clumsy, down on one knee and then the other, and then sitting more or less sideways. I was all but panting, and I felt sweat run under the suit, but my legs felt the relief, and finding a way to rest the corner of the lifesupport unit against the deck gave me delirious relief from the weight.

Bang. Thump.

Be careful, Beast, I thought at it, imagining all its minions and ourselves blown to atoms, to drift and swirl out there amongst the chaos-stuff. In one part of my mind—I think it was listening to the wrong kind of tapes—I was glad of a chance like that, that we might do some terrible damage to our attackers and maybe put a hole in the side of the wheel that they would remember ... all, all those scaly bodies going hurtling out amongst our fragments.

But in the saner part of my mind I did not want to die.

And oh, if they should get their hands on us. ... Hands. If they had hands at all. If they thought anything close to what we thought.

If, if, and if. Bang. Thump. Griffin and my lady told stories—recollected a day at Brahmani Dali, and smiled at each other. “I love you,” Griffin said then to Dela, a sober, afterthinking kind of voice, meaning it. I knew. I focused beyond them at Lance, and his face looked only troubled as all our faces did. It was no news to him, not now.

So we sat, and shifted our weight because the waiting grew long.

“They could take days about it,” Dela said.

“I doubt it,” Griffin said.

“They’ll suit up,” Gawain said. “They’ll have that weight to carry, just like us.”

“I wish they’d get on about it.” That plaintive voice from Vivien. Her eyes were very large in the dim light of the corridor, where the makeshift bulkhead had cut off some of the lighting. “What can they be doing out there?”

“Likely assuring their own safety.”

“They can’t come at us with firearms,” Lynn said. “If we can’t use them, they daren’t.”

“That’s so,” Dela breathed.

“Not at close range,” Griffin said. He laughed. “Maybe they’re hunting up weapons like ours.”

That would be a wonder, I thought. I was encouraged by the thought—until I reckoned that the odds were still likely theirs and not ours. And then the realization settled on me darker and heavier than before, for that little breath of hope, that we really had no hope at all, and that we only did this for—

When I thought of it, I couldn’t answer why we tried. For our born-men, that was very simple ... and not so simple, if there was no hope. It was not in our tapes—to fight. But here was even Vivien, clutching a spear across her knees, when I knewher tapes were hardly set that way. They made us out of born-man material, and perhaps, the thought occurred to me, that somewhere at base they and we were not so different—that born-men would do things because it leapt into their minds to do them, like instincts inherent in the flesh.

Or the tapes we had stolen had muddled us beyond recall.

The sound stopped again, close to us, though it kept on above. “They’ve arranged something, maybe,” Dela said. “God help us.”

“Easy,” Griffin said. And: “When it comes—understand, Dela, you and Elaine and Vivien take your position back just ahead of the crosspassage. If anything gets past us you take care of it.”

“Right,” Dela said.

If.It seemed to me a very likely if, recalling that flood of bodies I had seen within our lock.

But the silence went on.

“Lady Dela,” Percy said then, very softly.

Dela looked toward him.

“Lady Dela, you being a born-man—do you talk to God?”

My heart turned over in me. Viv’s head came up, and Lance’s and Gawain’s and Lynn’s. We all froze.

“God?” Dela asked.

“Could you explain,” Percivale went on doggedly, stammering on so dreadful an impertinence, “could you say—whether if we die we have souls? Or if God can find them here.”

“Percy,” Viv said sharply. “Somebody—Percy—”

Shut him up, she meant—right for once; and I put out my hand and tugged at his arm, and Lance pulled at him, but Percy was not to be stopped in this. “My lady—” he said.

My lady had the strangest look on her face—thinking, looking at all of us—and we all stopped moving, almost stopped breathing for Percy’s sake. She would hurt him, I thought; I was sure. But she only looked perplexed. “Who put that into your head?” she asked.

No one said, least of all Percy, whose face was very pale. No one said anything for a very long time.

“Do you know, lady?” Percy asked.

“Dear God, what’s happened to you?”

“I—” Percy said. But it got no further than that.

“He took a tape,” Vivien said. “He’s never been the same since.”

“It was me,” I said, because she left me nothing more to say. “It was the tape—The tape.” I knew she understood me then, and her eyes had turned to me. “It was never Percy’s fault. He only borrowed it from me, not knowing he should never have it. We—all ... had it. It was an accident, lady Dela. But my fault.”

Her eyes were still fixed on me, in such stark dismay—and then she looked from me to Lance, and Gawain and Lynette and Vivien and Griffin and last to Percivale, as if she were seeing us for the first time, as if suddenly she knew us. The dream settled about us then, wrapped her and Griffin too.

“Percivale,” she said, with a strange gentleness, “I’ve no doubt of you.”

I would have given much for such a look from my lady. I know that Lance would have. And perhaps even Vivien. We were forgiven, I thought. And it was if a great weight left us all at once, and we were free.

Vivien, whose spite had spilled it all—looked taken aback, as if she had run out of venom, as if she found a kind of dismay in what she was made to be. Maybe she grew a little then. At least she had nothing more to say.

And then a new sound, a groaning of machinery, that clanked and rattled and of a sudden a horrid rending of metal.

“O my God,” Dela breathed.

“Steady. All of you.”

“They’ve got the lock,” Lynn surmised. And a moment more and we knew that, because there was a rumbling and clanking closer and closer to the makeshift bulkhead behind which we sat. I clenched my handful of spears, ready when Griffin should say the word.

“Helmets,” he said, reaching for his.

I dropped the spears and picked up my lady’s, to help her, small skill that I had. But Percy took it from my hands, quick and sure, and helped her, as Lynn helped me. The helmet frightened me—cutting me off from the world, like that white place of my nightmares. But the air flowed and it was cooler than the air outside, and Lynn took my hand and pressed it on a control at my chest so that I could hear her voice.

“... your com,” she said. “Keep it on.”

I heard other voices, Lance’s and Griffin’s as they got their helmets on and got to their feet. Griffin helped Dela stand and Percy got me on my feet so that I could lean on my spears and stay there. Everything was very distant: the helmet which had seemed for a moment to cut off all the familiar world from me now seemed instead to contain it, the cooling air, the voices of my comrades. It was insulation from the horrid sounds of them advancing against our last fortification, so that we went surrounded in peace.

“Get back,” Griffin said; and Dela reached out her hand for his and leaned against him only the moment—two white-suited ungainly figures, one very tall and the other more suit and lifepack than woman. “Take care of her,” Griffin wished us, all calm in the stillness that went about us.

“Yes, sir,” I said. “We will.” We meaning Viv and I. And Dela came with us, a slow retreat down the corridor, so as not to tire ourselves, the three of us armed with spears. Dela kept delaying to turn and look back again, but I didn’t look, not until we had reached the place where we should stand, and then I maneuvered my thickly booted feet about and saw Lance and Griffin and the crew who had determined where theywould stand, not far behind the bulkhead. Their backs were to us. They had their swords and a few weighted pipes that Gawain and Lynn had brought down, and a spear or two. They stood two and three, Lance and Griffin to the fore and the crew behind. And I felt vibration through my boots, and heard their voices discussing it through the suit com, because they had felt it too.

“It won’t be long,” Griffin said. “We go forward if we can. We push them out the lock and get it sealed.”

“They may have prevented that,” Gawain said, “if they jammed something into the track.”

“We do what we can,” Griffin said.

Myself, I thought how those creatures had gotten up against us, and wrenched the second door apart with the sound of metal rending, a lock that was meant to withstand fearful stress. Modred’s had been a small betrayal; it lost us little. They could easily have torn us open—when they wished, when they were absolutely ready.

“Feel it?” Dela asked.

“Yes,” I said, knowing she meant the shuddering through the floor.

“They can’t stop them,” Viv said.

“Then it’s our job,” I said, “isn’t it?”

The whole floor quivered, and we feltthe sound, as suddenly there was a squeal of tearing metal that got even through the insulating helmets. Light glared round the edges of the bulkhead where it met the overhead, and widened, irregularly, all with this wrenching protest of bending metal, until all at once the bulkhead gave way on other sides, and drew back, showing a glare of white light beyond. The bulkhead was being dragged back and back with a terrible rumbling, a jolting and uncertainty until it dropped and fell flat with a jarring boom. A head on a long neck loomed in its place. For a moment I thought it alive; and so I think did Griffin and the rest, who stood there in what was now an open access—but it was machinery silhouetted against the glare of floods, our longnecked dragon nothing but a thing like a piston pulling backward, contracting into itself, so that now we saw the ruined lock, and the flare of lights in smoke or fog beyond that.

“Machinery,” I heard Lance say.

But what came then was not—a sinuous plunge of bodies through the haze of light and fog, like a cresting wave of serpent-shadows hurling themselves forward into the space the machinery had left.

My comrades shouted, a din in my ears: “ Come on!” That was Griffin: he took what ground there was to gain, he and Lance—and Gawain and Lynn and Percy behind them, two and then three more human shadows heading into the wreckage and the fog, tangling themselves with the coming flood.

“Come on,” my lady said, and meant to keep our interval: I came, hearing the others’ sounds of breath and fighting—heard Griffin’s voice and Lance’s, and Lynn who swore like a born-man and yelled at Gawain to watch out. We ran forward as best we could, behind the others. “No!” I heard Viv wail, but I paid no attention, staying with my lady.

And oh, my comrades bought us ground. Shadows in the mist, they cut and hewed their way with sobs for breath that we could hear, and no creature got by them, but none died either. We crossed the threshold of the rained bulkhead, and now Griffin pushed the fight into the lock itself, still driving them back. “Wait,” I heard, Viv’s voice. “Wait for me.” But Dela and I kept on, picking our way over the wreckage of the fallen bulkhead, then past the jagged edges of the torn inner lock.

And then they carried the fight beyond the lock, in a battle we could not see ... driving the serpent-shapes outside.

But when we had come into the lock, my lady and I, and Vivien panting behind us—it was all changed, everything. I knew what we shouldsee—an access tube, a walkway, something the like of which we had known at stations; but we stared into lights, and steam or some milky stuff roiled about, making shadows of our folk and the serpents, and taller, upright shapes behind, like a war against giants, all within a ribbed and translucent tube that stretched on and on in violet haze. “Look out!” I heard Lance cry, and then. “Percy!”

And from Lynette: “He’s down—”

“Dela—” Griffin’s voice. “Dela—”

“I’m here,” she said, wanting to go forward, but I held her arm. They had all they could handle, Griffin and the rest.

“Fall back,” I heard him say. “We can’t go this—Get Percy up; get back.”

They were retreating of a sudden as the other, taller shapes pressed on them like an advancing wall. I heard Gawain urging Percy up; saw the retreat of two figures, and the slower retreat of three. “Back up,” Griffin ordered, out of breath, and then: “Watch it!”

Suddenly I lost sight of them in a press of bodies. I heard confused shouting, not least of it Dela’s voice crying out after Griffin; and Gawain and Percy were yelling after Lance and Griffin both.

But still Griffin’s voice, swearing and panting at once, and then: “You can’t—Lance, get back, get back.– Dela!—Dela, I’m in trouble. I can’t get loose—Modred—Get Modred—”

“Modred,” Dela said. She turned on me and seized my arm and shook at me so that I swung round and looked into her eyes through the double transparency of the helmets. “Let him loose—let Modred loose, hear?”

I understood. I gave her my spear and I plunged back past Viv, back through the lock again and over the debris—no questioning; and still in my suit com I could hear my comrades’ anguished breaths and sometimes what I thought was Lance, a kind of a sobbing that was like a man swinging a weight, a sword, and again and fainter still ... Griffin’s voice, and louder—Dela’s.

“Get them back,” I heard. That was Lance for sure; and an oath: that was Lynette.

I had the awful sights in my eyes even while I was feeling my overweighted way over the debris in the corridors; and then my own breath was sobbing so loud and my heart pounding so with my struggle to run that the sounds dimmed in my ears. I reached the open corridor; I ran in shuffling steps; I made the lift and I punched the buttons with thick gloved fingers, knees buckling under the thrust of the car as it rose, one level, another. Up here too I could hear a sound ... a steady sound through the walls, that was another attack at us, another breaching of the Maid’s defense.

Get Modred.There was no one else who might defend the inner ship, and that was all we had left. I knew, the same as my lady knew, and I got out into the corridor topside and shuffled my clumsy way down it with my comrades’ voices dimmed altogether now, and only my own breaths for company.

I pushed the button, opening it. Modred had heard me coming—how could he not? He was standing there, a black figure, just waiting for me, and when I gestured toward the bridge he cut me off with a shove that thrust me out of the way ... ran, the direction of the bridge, free to do what he liked.

“Go,” his voice reached me over com, in short order, but I was already doing that, knowing where I belonged. “Elaine ... get everyone out of the corridors.”

“Modred,” Dela said, far away and faint. “We’re holding here ... at the lock. We’ve lost Griffin—”

“Get out of the corridors,” he said. “Quickly.”

I made the lift. I rode it down, into the depths and the glare of lights beyond the ruined corridor. They might have taken it by now, I was thinking ... I might meet the serpent shapes the instant the door should open; but that would mean all my friends were gone, and I rushed out the door with all the force I could muster, seeing then a cluster of human shapes beyond the debris, three standing, two kneeling, and I heard nothing over com.

“My lady,” I breathed, coming as quickly as I could.

“Elaine,” I heard ... her voice. And one of the figures by her was very tall, who turned beside my lady as I reached them.

Lance and my lady and Vivien; and Gawain and Lynette kneeling over Percivale, who had one arm clamped tight to his chest, his right. But of Griffin there was no sign; and in the distance the ranks of the enemy heaved and surged, shadows beyond the floods they had set up in the tube.

“Modred’s at controls,” I said, asking no questions. “He’ll do what he can.” And because I had to: “I think they’re about to break through up there.”

My lady said nothing. No one had anything to say.

Modred would do what was reasonable. Of that I had no least doubt. If there was anything left to do. We were defeated. We knew that, when we had lost Griffin. And so Dela let Modred loose, the other force among us.

“Lady Dela,” Modred’s voice came then. “I suggest you come inside and seal yourselves into a compartment.”

“I suggest you do something,” Dela said shortly. “That’s what you’re there for.”

“Yes, my lady,” Modred said after a moment, and there was a squealing in the background. “But we’re losing pressure in the topside lab. I think they’re venting our lifesupport. I’d really suggest you take what precautions you can, immediately.”

“We hold the airlock,” Dela said.

“No,” Modred said. “You can’t.” A second squealing, whether of metal or some other sound was uncertain.

And then the com went out.

“Modred?” Dela said. “Modred, answer me.”

“We’ve lost the ship,” Lynette said.

“Lady Dela—” Lance said quietly. “They’re moving again.”

They were. Toward us. A wall of serpents and taller shapes like giants, lumpish, in what might be suits or the strangeness of their own bodies.

Dela stopped and gathered up a spear, leaned on it, cumbersome in her suit. “Get me up,” Percy was saying. “Get me on my feet.”

“If they want the ship,” Dela said then in a voice that came close to trembling, “well, so they have it. We fall aside and if we can we go right past their backs. We go the direction they took Griffin, hear?”

“Yes,” Lance said. Gawain got Percy on his feet. He managed to stay there. Lynette stood up with me and Vivien. Out of Vivien, not a word, but she still held her spear, and it struck me then that she had not blanked: for once in a crisis Vivien was still around, still functioning. Born-man tapes had done that much for her.

The lines advanced, more and more rapidly, a surge of serpent bodies, a waddle of those behind, beyond the hulking shape of the machinery they had used to breach us, past the glare of the floods.