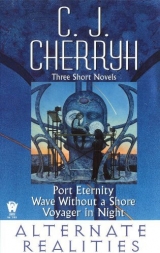

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

X

Master Herrin Law: Does emotion originate from within or without your reality?

Apprentice: Within. There are no external events.

Master Law: Is the stimulus to emotion also internal?

Apprentice: Sir, no external events exist.

Master Law: Am I within your reality?

Apprentice: (Silence).

Master Law: That is a correct answer.

Waden Jenks tolerated the sitting, suffered in silence, because to admit discomfort and then go on to bear it was to admit he was constrained. Herrin prolonged the misery in self-contained humor, took whatever shots might be minutely necessary, sketched from several angles, after resetting the lighting with meticulous care.

And Waden, perched on his uncushioned chair, sat rigidly obedient.

“The lighting,” Herrin said, “will be from a number of sources. I take the seasons into account; apprentices are running the matter in the computer, so that the lighting will be exact from season to season, the sun hovering hour by hour in a series of what appear to be design-based apertures. The play of—”

“Spare me. I’ll see the finished effect. I trust your talent.”

Herrin smiled, undisturbed. Darkened an area beneath the chin and smiled the more.

“A little haste,” said Waden. “I have appointments.”

“Ah?”

“A ship in orbit. An ordinary thing.”

“Ah.”

“There is some hazard. This is McWilliams’s Singularity.”

Herrin lifted an eyebrow, nonplused.

“An irregular client, one of the more troublesome. I’d like you to be there, Artist.”

Both eyebrows. “Me? Where, at the port?”

“The Residency, my friend.”,

“What, you want sketches?”

Waden smiled. “I find the opinion of the second mind of Freedom—an asset. You have an insight into character. I value your assessment. Observe the man and tell me what you’d surmise about him.”

“Interesting. An interesting proposal. I bypass your naïve assumption. I’ll come.”

“Of course you will.”

He stopped in midshadow, made it a reflective pause, studiously ignoring Waden, refusing at this moment to interpret him.

XI

Apprentice: Master Law, what is the function of Art in the State?

Master Law: The question holds an incorrect assumption.

Apprentice: What assumption, sir?

Master Law: That Art is in the State.

And on the morrow the shuttle was down and Camden McWilliams was in the Residency.

Herrin wore Student’s Black; it was stark and sufficiently dramatic for confrontations. He sat in the corner of Waden’s office, refusing to be amazed at the splendor of the decoration, much of the best of the University culled for the private ownership of the First Citizen. He knew the individual styles: the desk with the carved legs, definitely Genovese; the delicate chair which bore Waden’s healthy weight, Martin’s; the paintings, Disa Welby; the very rugs on the floor, work of Zad Pirela, meant as wall hangings, and here trod upon as carpet.

He was offended. Vastly offended. He observed, catalogued, refused to react. It was Waden’s prerogative to treat such things with casual abuse, since Waden had the power to do so; he recovered his humor and smiled to himself, thinking that there was one work Waden could not swallow, but which engulfed him.

Meanwhile he sketched, idly, and looked up with cool disinterest when functionaries showed in captain Camden McWilliams.

A black man of outlandish dress, bright colors, a big man who assumed the space about him and who had probably given the functionaries difficulty. Waden greeted McWilliams coldly, and Herrin simply smiled and flipped the page of his sketchbook to begin again.

“McWilliams of the irregular merchanter Singularity,” Waden Jenks said, failing to hold out his hand. “Herrin Law, Master of Arts.”

“McWilliams,” Herrin said cooly.

McWilliams took him in with a glance and frowned at Waden. “Wanted to see,” he began without preamble, “what kind of authority we have here. You’re old Jenks’s son, are you?”

“You’ve been informed,” Waden said. “Come the rest of the way to your point, McWilliams of Singularity.”

“Just looking you over.” McWilliams studiously spat on the Pirela carpet. “Figure the same policies apply.”

“I follow old policies where pleasant and convenient to me. That I see you at all is more remarkable than you know, for reasons that you won’t understand. Outsiders don’t. You’ll accept the same goods at the same rate and we’ll accept no nonsense. Trade here is not necessary.”

“We,” said McWilliams, “have the ability to level this city.”

“Good. I trust you also have the ability to harvest grain and to wait about while the new crop grows. Perhaps the military will assist with the next harvest.”

McWilliams chuckled softly and spat a second time. “Good enough, Jenks. Go on about your business. We’re loading at port. You know my face now and I know yours.”

“Sufficient exchange, McWilliams.”

“What’s this—thing—in the city?”

“Thing, McWilliams?”

“This thing in the middle of town. Scan doesn’t lie. What are you doing out there?”

“Art. A decorative program.”

McWilliams’s eyes rested coldly on him. “Nothing military, would it be?”

“Nothing military.” For once Waden Jenks looked mildly surprised. “Take the tour, McWilliams. There’s no restriction in Kierkegaard. Wander our streets as you will.”

“ Thiscity? Hell, sooner.”

“The driver will take you to the port.” Waden made a temple of his hands and smiled past them. “A safe trip, McWilliams.”

“Huh,” McWilliams said, and turned and walked out.

Herrin filled in a line, shadowed an ear, languidly looked up into Waden’s waiting eyes. “Barbarian,” he judged. “Limited in formal debate but abundantly intelligent. Canhe level the city?”

“Undoubtedly.”

Herrin’s insouciance failed him. For a moment he almost credited Waden with humor at his expense, and then revised his opinion.

“Freedom,” said Waden Jenks, “navigates a black and perilous sea, Herrin. And Iguide it. And I see the directions of it. And I shape things beyond this city, beyond Sartre, beyond Freedom itself. I am a power in wider affairs, and when they come calling ... I deal with them. This much you should see, when you portray me, Herrin Law.”

For a moment Herrin was taken aback, “My art will encompass you,” he said. “And comprehend you in all senses of the word. The man saw my work, did he not? From that great height, he saw it.”

“That pleases you.”

“It’s an intriguing thought.”

“Their vision is considerably augmented to be able to do it. Kierkegaard is a very small city, by what I know.”

“We are at our beginning.”

“Indeed. So am I. Freedom is my beginning, not my limit.”

“We once talked of hubris.”

“And discounted it. Shape your stones, Artist. My way is scope. We talked about that too. You’ll never see the posterity you work toward. You’ll only hope it exists ... someday. But I’ll see the breadth I aim for.”

“But not the duration.”

The words came from his mouth unchecked, unthought, un-cautious. For a moment Waden’s smile looked deathly, and a very real fear came into his eyes.

“You serve my interests. Go on. Pursue your logic.

“You’ll carry my reputation with yours.” Herrin followed the argument like a beast to the kill, savoring the moment, hating the role in which perpetual caution had cast him with this man. “Mutual advantage.”

Waden smiled. That was always a good answer. It was effective, because he had then to wonder if Waden conceived of an answer. It was possible that Waden did; his wit was not easily overcome.

And Herrin smiled, because it was a good answer for him to return.

So henceforth alone, he thought firmly. Each to his own interests.He was linked to Waden in one way and severed from him irrevocably in another, because the war was in the open.

“You’ve seen,” Waden said, “all that could interest you. I won’t keep you from your important work.”

Herrin slowly completed a line, shaded one, sealing the image of the foreigner in all his dark force. Flipped the notebook shut and rose, left without even an acknowledgment that there was anyone else in the room but himself.

Creative ethics, Keye called it.

But in fact the visit did shake him; and when he walked out under the sky, leaving the Residency, he could not but think of a vast machine orbiting over their heads, observing what passed in Kierkegaard from an unassailable height ... that there was a force above them which had a certain power over their existence.

He did not look up, because of course there was nothing of it to be seen; and he shrugged off the feeling of it. Laughed softly, at the thought that Freedom ignored outside forces as they ignored the invisibles; that in effect he had just spent a time talking to an invisible.

The man had spat on the Pirela weavings, had spat to contemn Waden Jenks and all Freedom, and Waden had treated that affront as invisible too, but it did not remove the spittle from the priceless artwork.

That man, the thought kept insinuating itself into his peace of mind, that man despised the greatest political power on Freedom, and the work of one of Freedom’s great artists, and walked out, because there had been nothing to do.

Waden Jenks might have had him killed on the spot. Might have, potentially. But that ship was still up there with the power to level Freedom. Camden McWilliams had refused the rare chance for a closer sight of Kierkegaard, from fear? from distrust? ... or further contempt?

He refused to think more on such matters. The man was an invisible. Meditating on invisibles was unproductive. Invisibles had nothing to do with reality, having rejected their own.

The analogy was incomplete: the ship and Camden McWilliams possessed power.

Herrin shivered in the daylight and walked on the way that the outsider had rejected, into the town.

The work progressed. He reached the Square, where the eighth course of stone was being moved into place, and even while that work progressed, apprentices were at work on the lowermost courses, some mapping the places to cut, some actually cutting with rapid precision, so that already the three shells, the touch-points of the interior curtain-walls, and the foot of the central support, showed some indication of shaping, troughs, folds, incisions.

A further portion of the view which had existed on this site since the initial layout of Kierkegaard—was gone. He refused to look up toward Keye’s apartment. She might be there, might be at the University. She would spend her evenings at least contemplating what went on below. The noise would intrude on her sleep, impossible for her to ignore. He wondered how she reasoned with that.

He walked round the structure, actually inside it with a palpable feeling of enclosure. The art of it began. Other walkers, ordinary citizens, had ventured into it cautiously, because it sat in the main intersection of Kierkegaard. They gawked about them in spite of their personal dignity, avoiding the ominous machinery, touching the stone in furtive curiosity. This satisfiedhim. He found himself immensely excited when he watched a stray child, more outward than her elders, stand with mouth open and then run the patterns of the curving walls until a stern parent collected her.

And for the second time, he saw one of the Others.

The workers saw nothing, nor did the walkers, who continued without attention to it, perfectly in command of their realities at least as regarded invisibles.

But Herrin saw it, midnight-robed, walking through the structure, lingering to examine it as the child had, walking the patterns.

And that did not satisfy him. He turned from the sight, trying to pretend to others that he had noticed nothing, and perhaps their own concentration on their own reality was so intense that they could not notice his action in connection with the apparition.

Suddenly he suffered a further vision. Having seen the one midnight robe, he saw others on the outskirts, standing there, outside one of the half-built gateways. Three figures. He was not aware whether he noticed them now because he had seen the one and the shock of the night encounter was still powerful, or perhaps it was in fact the Work which drew them, and they had never been there before.

He wiped them from his mind, turned to his own work, which was the central column. Leona Pace was not at hand, presumably being off about some important business. He interrupted an apprentice to look at diagrams, found everything in order, bestowed no compliments. They were not expected to exercise their own inspirations, but to execute his, and they were all doing so with absolute precision: had any failed, that one would have been discharged with prejudice. He pushed the apprentice aside, made a minor change, sketching with black on the stone itself, and the apprentice obediently altered the computer-generated sheet which was the master plan.

So doing, he put himself back to work and put the external from his mind. He worked until suppertime, and involuntarily thought of Keye, looked from the incomplete hemisphere of the dome, and saw the warmth of her window light in the dusk. He recalled sweet scents and a meticulous order, and the servant’s excellent taste, and suffered a spasm of regret for their continued separation. His mind flashed back to Law’s Valley, and to other such warm comforts, now lost. He prepared to make his solitary way back to University, and left the work in the capable charge of Leona Pace, who had returned from the shipping terminal and her own selection of the stone, a zeal he silently approved. Pace looked shadowed, hungry, exhausted; she kept at the work nonetheless, for her reasons, probably having to do with insecurity in her subordinates. He did not blame her: Pace was extraordinary, and anyone of lesser ability had to be a frustration and a worry to her.

He valued Pace, might have made closer acquaintance with her, with the thought of filling some of that solitude; there were looks he received from her which hinted a desire for his approval, which might lead to dependency on it, which might in turn lead to a relationship different and more controllable than he had known.

But no, experience of Keye and Waden argued caution was in order. Pace was zealous. Ambitious. He was at the moment too weary to deal with someone of ability and possible labyrinthine motive. Such entanglements with apprentices were all potential hazard.

Dinner, he told himself, at the Fellows’ Hall; he still wore his black, and he would be inconspicuous as Herrin Law could ever be. A solitary dinner. Solitary tea. Solitary bed.

XII

Master Keye Lynn: How do the realities of Freedom coexist?

Master Law: They don’t.

Master Lynn: How do you reconcile the realities of Freedom?

Master Law: I don’t.

Master Lynn: How are lower degrees of intelligence able to maintain their separate realities?

Master Law: They delude themselves, they’re part of mine.

He departed the structure, where lights had come on, glaring with their nightly brilliance, and walked along an increasingly deserted street past the ever-same buildings, taking no thought for his safety,

The slight traffic of Main vanished entirely at the hedge of Port Street. He passed through the arch of the firebushes, and experienced ever so slight a fear, outraged by it as soon as he had come out again into the deepening dusk of the street, out in front of the Residency, in which rows of lights showed interior life. He was not accustomed to fear. He was the most confident of men; had every reason for confidence. Suddenly he took on caution in harmless streets, as if there were something there which nagged at his attention, an eroding of safety, a thing which appeared only in the corner of the eye, as the blanking color of the Others and the invisibles had screened them from eyes which had learned not to see that color and that robed shape. He had never been so troubled, had never had such sick fantasies.

He was an Artist, and sawdetails which others could not see. That was his art.

And did he then, in his skill, begin to lose that ability which screened out madness and the irrational?

I, he insisted to himself, and looked to the Residency façade.

MAN IS THE MEASURE OF ALL THINGS. MAN. MAN ... and nothing else.

I.

There was a rumbling. Shuttles had come and gone at the port many times in his life in Kierkegaard; no one heard them or deigned to pay them notice, except those whose business it was to deal with the fact. But in the dark, and the slight chill, the disturbance of the air could not be ignored. The thunderclouds gathered like a summer storm, and he lifted his eyes to the far end of Port Street, where a light rose in the sky. And because he was alone and had no shielding distraction he found himself looking up, and up, and up, following the moving light of the shuttle, against a sky utterly black near the glare of the port lights, and then sprinkled with stars as the light climbed higher.

He was not wont to look up at all. He knew vaguely that the stars were suns like their own and that such suns had planets like their own and that organization drew those worlds together into complexities of politics. Knew that there were renegade powers, like Camden McWilliams. But for the first time he saw how manystars there were.

It was like looking down from a height, realizing that number. For a moment his balance deserted him. The Ibecame less than it had been, a reality valid on Freedom, in Freedom’s context.

Scope.Waden’s art reached for those points of light. His art—bound to Waden—would go out there. Waden called himself Apollonian, orderly, light-loving and logical, but what he perceived in that scattering of dust was disquietingly Dionysian, chaotic, dark, and random.

Why do they stay in order?he wondered of the stars; and recalled half-heard tapes of natural structure, and forces, and his own art, which had to do with the architecture of a dome, and of inner, chemical structures of stone, vision plummeting from macroscopic to microscopic in one dizzying contraction and out again. He realized that he was staring, that someone might see him and think him gone mad, but he had never been concerned for the opinions of lesser minds; had disturbed Jenks Square with equanimity, uncaring. Now he felt exposed, catching a glimpse of something, like the Others, which refused to fit.

I, he reminded himself, defying the stars, and lowered his eyes to the street and walked across it.

Why?The question echoed in his mind, unwelcome; along with how far?and how wide?and how old?

I.

The invisibles looked at Reality and flinched from it, retreating into madness. His art was to see, and to go on seeing. It occurred to him that something dangerous was happening, that he had started a chain of events which led precipitately somewhere, and there was no stopping it.

He heard Waden asserting an exterior reality as valid. The University had been founded for Waden.

And might not other things have served Waden Jenks?

If he were sane, he thought, he would back off from such questions, which kept demanding others and others until the perspectives went spiraling up and down from molecule to star and back again.

He kept walking, past the safe front of the University, ignoring the hunger which he had nursed past a neglected lunch, the faint savor of food in the air from all the houses in Kierkegaard. He followed the avenue, which was deserted, and came closer and closer to the port.

Fear was there. He knew that it was. Fear was what he pursued. He walked as far as the open gate in the wire fence which ran the circumference of the port area—fenced for what reason was not clear, for there were no guards, no one defending the access. There were lights, glaring in the night like the lights which he could see if he looked back, where the glow of the work in Jenks Square lit the darkness above the hedges and the tops of buildings. Lights glared in the area from which the shuttle itself might have lifted, a bare circle, of machinery fit with floodlamps all up and down its ugly and yet interesting height, like the cranes which labored to place the stone in Jenks Square.

And figures, robed, walked among booths garishly draped under the fieldside floods. He stared, recognizing them as Others, or invisibles, there for trade.

He knew that invisibles somehow pilfered by night in the port market, where citizens of Kierkegaard traded by day, disdaining any robed intruders out of their time, but there was no mention that thiswent on by night, organized, booths manned—if they weremen—money changing hands from opened cashboxes. ...

He walked farther, facing fear, because it was there, as he would have faced down Waden or Keye or anyone else fit to rival him. Fear ran the aisles, skipped along almost visibly in the rippling shadows of robes which should have been invisible to his trained perceptions; but it was night, and robes cast shadows, and shadows were everywhere, There was no one like himself, a citizen. Pilfered goods disappeared and no one cared to complain, because had the invisibles been a problem, something would have been done about it, the solution so often proposed and never, because they did not care for the untidiness, carried out.

To kill them all, some had argued in University, would remove a blight. And whoever proposed the solution stood self-consciously admitting that they existed.

And who knows how many there are? another had proposed. Or how we should track them all? They do no harm.

In point of fact, no one knew ... how many there were, who had gone mad. No one knew how many ahnit there were, or how many robes here might conceal one or the other. The invisibles had stopped being human.

Perhaps they bred, making more invisibles. If so they were quiet about it, and perhaps the offspring, lacking proper care, died; no one asked. No one noticed. It was not good health to take overmuch thought in the matter.

As for ahnit, they were not even in basic question. They were a separate rationality. The proper study of man is man,the maxim ran.

Who had proposed such a thing, when their ancestors had been merchants, or at least merchants had been among their ancestors? Who had made the decisions, when they found this perfect world that was Freedom and laid down the Reality which existed here? A Jenks?

But once ... all their ancestors had been up, out there, far away.

Once....

He cancelled that reality, preferring to start time over again. It was his Reality, his option. He smiled self-confidently, walked up to a booth manned by an invisible and found the meat pastry there attractive. He gathered up two of the hot pies, not seeing the invisible who sat there watching him, and humorously walked away, eating the invisible pie and quite pleased with the taste of it. Men could pilfer under the same law as invisibles. No one was going to ask him for payment. No one dared, because they did not want to be noticed.

Much more savory than what was served in the Fellows’ Hall. He recalled an old saying about stolen fruit and, finishing one pie, sought a beer amongst the booths.

Quite a different reality, he thought, intrigued now that the disturbance of the day had been settled—food was what he had evidently needed to settle his stomach and his metaphysics. He was fascinated by the swirl of no-color and no-substance against the powerful glare of the port lights where the shuttle had gone back to the invisible ship and its invisible threat. Quite, quite fascinating, this walk through an invisible’s dream of reality, where madmen went about commerce and no-men stalked about on their own inscrutable business.

There must be a certain economy to allow it to function. Sane farmers grew crops, which invisibles pilfered, which in turn hepilfered, and it all somehow balanced, because what was pilfered was sold, turnabout day and night and his small consumption merely fed the engine that was Kierkegaard and Sartre itself, which fed this mass as well as the daylight trade.

And how did the ahnit fit in? Some of the goods in the booths—the clothes—the robes which ahnit and men wore ... ahnit robes. Ahnit Jewelry. He paused and tooka piece, turned it in his hand, found it, with its convolute patterns, of passing skill. He pinned it to his collar, laughing at the conceit. An economy which functioned on universal theft, with sales only among like and like; founded on the principle that no one stole, just pilfered. He walked on, saw one of the University stamped hammers for sale, doubtless pilfered from Jenks Square, from hiswork. Amazing. He declined to repossess it. It was a minor item and heavy to be carrying about. Let them have it.

He found his drink in a brightly draped booth which passed out an assortment of mugs. He appropriated what was destined for another hand, right from under the invisible’s reach, and walked his way, consuming his second pie, tasting cool beer and dazzled by amazements right and left.

When he had done he set the mug down, reckoning it would be pilfered back along the circuitous route, likely back to the very same booth from which he had taken it. Nothingcould get lost in the labyrinthine system. He had lived within it all his life and had never quite seen it so clearly delineated, so vividly exercised ... for even in Law’s Valley things had vanished, to turn up again in market in Camus, and it was not good form to question.

Kill the invisibles? He wondered. How would civilization survive if not for them? Where would be the humor in that?

Not to go searching the market for a lost plowshare? Not to have the confidence it would turn up again? No one ever hungered because of it. And a good many times were never missed, or were missed with gratitude, and discovered by another with pleasure, whenever some citizen bought it back again. This was somewhat like the country markets, indeed it was, and the few new-goods warehouses in town were dull by comparison. Only in Camus there had been just the Place, where goods tended to appear, and remain, and perhaps—he had never wondered—there was also this nighttime activity.

By day, simple citizens; by night, invisibles. The same merchandise.

A balance, indeed.

He had quite shed his fear and walked now in utter abandon.

An ahnit set itself in his path, and from within the hood a glitter of eyes regarded him with such directness that he forgot himself, and stopped, and then had to recover his self-possession and walk around the obstacle, instead of employing that graceful sidestep one used when the obstacle was expected. He was shaken. It was deliberate. It was very near aggression. The thought occurred to him that if a citizen should ever be found dead in Kierkegaard—and it happened—the inquiry did not extend beyond citizens and natural causes.

He kept going in his chosen path, which took him again to the gate, and to Port Street.

He looked back. For the first time in his adult life he committed such an indiscretion, and there was an ahnit there.

A shadow, a robed shadow on the street, beneath the lights by the gate. It had followed.

He had looked—and never meant to again—but this one time he had looked, simply to prove himself wrong. His apprehension had been correct, and thereafter, alone or in public, whenever beset with the temptation to yield to the urge to look behind him, whenever insecure in his own reality he would remember ... once ... there had been something there. He shivered. He hurried.

The University doors received him, solid wood, carved, safe and sturdy. They closed behind him and he walked down the corridors toward Fellows’ Hall, hearing the slight boisterousness from it long before he reached it. He sought the familiar, the banal, desperately.