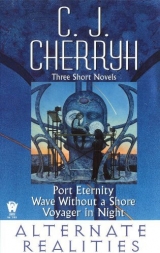

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

XXVIII

Master Lynn: Where were you?

Waden Jenks: Where I chose. Is that your concern?

Master Lynn: You were out there again. In the Square. Consider your appearance. You pay homage to that thing. Your curiosity has you, not you it.

Waden Jenks: I find its counsel superior.

Master Lynn: He was your enemy. Do you consider that?

Waden Jenks: Are you my friend?

Master Lynn: Is anyone, Waden Jenks?

There was no particular direction. Sbi walked east, this day, and sat down after a time, munching a grass stem, and seemed content to sit. Herrin lay down full length on his back and stared at the clouds drifting, fleecy white and far, with such a weight on his mind that it seemed apt to break.

“Sbi,” he said at last, “teach me.”

“Teach you what, Master Law?”

“My name is Herrin.”

“Herrin. Teach you what?”

“What reality is.”

“What do you see?”

“Sky.”

“What do you feel?”

“Pain, Sbi.”

“Both are real.”

“Whose reality?”

“Everyone’s.”

“What,” he snorted, having finally discovered Sbi’s depth, “ everyone’sforever and however far? That’s hardly reasonable.”

“Throughout all the universe.”

“You’re mad.”

Silence.

“How can external events be real to you, Sbi?”

“I feel them.”

It angered him. In frustration he slammed his hand against the ground and rolled a defiant look at Sbi, with tears of pain blurring his eyes. “You tell me you felt that.”

“Yes. All the universe did.”

Sbi proposed an insanity. He retreated from it, simply stared at the clouds.

“I’ve taught you,” said Sbi, “all I know.”

“You mean that I’m not able to perceive it.”

“Where shall we go, Herrin?”

He bit down on his lip, thought, trying to draw connections through the maze of Sbi’s logic. He gave up. “How long are you prepared to sit here, Sbi?”

“Is this where you wish to be, then?”

“What does it matter what I want?”

Silence.

“Sbi, I was wrong. I’ve spent my life being wrong. What can I do about it?”

Silence. For the first time he understood that answer. He turned on his side and looked at Sbi, who sat chewing on another grass stem. His heart was beating harder. “What were you waiting for all those years in the city? For me? For someone who could see you?”

“Yes.

“And what difference does it make whether I see you?”

Silence.

“It makes a great deal of difference, doesn’t it, Sbi?”

“What do you think?”

“That it makes everything wrong. That the whole world is crazy and I’m sane. Where does that leave me, Sbi?”

“Invisible. Like me.”

He found breathing difficult, not alone from the bandage. He pushed himself up on his elbow. “You had to let me go back to my own house to find that out.”

“I had no idea what would happen. Reality is not in my control. Nor are you.”

“You’ll wander all over Sartre taking care of me if that’s what I decide, is that so?”

“I will stay with you, yes. And keep you from harm if I can.”

“Why?”

Sbi sucked in the grain-bearing head and chewed it. “Because I want to. Because when you struck your hand I had the pain, Herrin.”

“I could ask you; I could ask you question after question and when I got close to what I really want to know you’d say nothing.”

“The important questions are for you to answer. It is, after all, your world that’s in jeopardy; mine is long past that.”

“Why were you among us?”

“If someone had destroyed your world, would you not have an interest in those who had done so?”

“They did. And I don’t want to go back. I don’t want to see them again or be seen.”

Sbi simply stared at him.

There was no relief for the silence, none. He sat up with his bandaged hands in his lap and contemplated them, flexed his hands slightly against the splints and bit his lip at the pain which won him no great degree of movement.

“Who broke your hands, Herrin Law?”

He shut his eyes, weary of the repeated question.

“Why?” Sbi asked inevitably.

He shook his head slowly, drew a breath which suddenly stopped in his throat. His eyes unfocused. He thought to Fellows’ Hall, a certain evening, and a conceit which had gripped them both, him and Waden. “I’d begun to see you. I’d begun to see things the way they were; and Waden was never dull. I think he saw too, Sbi. I think he did. He does. Sbi, I’m going back.”

“Yes,” said Sbi.

He had reached for the bundles of toweling and grass rope which were all his possessions; and suddenly he caught Sbi’s expression, and Sbi’s tone, and it was not the same as when he had proposed going to the valley. Then there had been disappointment, vague reluctance. Now it was different.

“You’ve pushed me to this,” he said, wrapping his arms about the bundles and staring at Sbi. “Sbi, have I guessed enough of what you want? Or do you go on the way you have?”

“I don’t know that you’re right,” Sbi said. “But your logic seems irrefutable save by Waden Jenks. I will tell you what I want, Herrin. I have found it: a human who can see. I’ll tell you what I’ve waited for all these years as you say ... to learn what that human will do, when he sees. But one thing frightens me: what those who don’t see will do to him.”

“They won’t be ableto see me,” he said, disliking Sbi’s proposition. But he thought about it. “There are the Outsiders, aren’t there? And they see.”

“To my observation—yes.”

He sank down off his heels and frowned with the pain and with the fear the pain set in him. He stared straight before him and thought about it for a long while.”

“Now it’s hiding,” he said finally.

“How, hiding?”

“Before, I was surviving. Now it’s hiding, staying up here in the hills. Now I don’t go back because I’m afraid. Or if I don’t go back I amafraid.” He rolled a glance at Sbi. “You’re good; you’ve had the better of me. You set it all up. Located the best of us ... studied how to intervene. You had your best chance when I came out of the University and worked in the open. Then you could get to me. Accosted me in the dark that night, on Port Street. That wasyou. Drove Leona Pace over the edge. Came back to plague me. Worked at me—constantly.”

“Yes,” said Sbi.

“Now I should go back to the city. Now I should take on Waden Jenks and finish drawing him into this.”

“Yes.

“Why, Sbi?”

“Our survival.”

“Reasonable,” he said, trying at least to admire the artistry of it.

“What are you going to do?”

He shook his head. “Surrender Freedom to your manipulation? That’s what you’ve set me up to do, isn’t it? Me, and Waden Jenks; one of us set against the other ... myself, taken out of influence; and on the other hand given the chance to change the world. I’m one of the invisibles. It occurs to me that murder is possible for one of us. That I can push Waden over the edge ... I can do that, because I’ve nothing to lose, have I? Or I can sit here in the hills and know that the greatest thing I ever did fitted your purpose.”

“All that humans have done is bent around us, Herrin Law. The way you live, the pains you take to ignore us, the insanity which claims some of you ... are these things spontaneous? Were you ever—reasonable?”

He stared at the horizon, colder and colder. “No,” he said.

“Herrin. I’ll go withyou. I’m concerned for you.”

He thought of the statue in the hills; of a small dead creature in Sbi’s hands; of Sbi’s hands caressing what Sbi had killed.

Of his parents going about their business not seeing him.

He rested his face against the back of his hand, wiped at the left eye. “So, well, tell me this, Sbi, what do you expect to happen?”

“I don’t know. But it will be of human choosing, and my choosing, both, my friend. Both at once. Is it not reasonable?”

It was, as Sbi said, reasonable. “I’ve taught students,” Herrin said. “I thought I knew, and thought I saw, and I taught. For them, I’m going back, and Waden ... I don’t know about Waden.” He struggled to his feet, started to bend for his belongings again, but Sbi anticipated him and caught them up.

“It’s not far,” Sbi said.

He had guessed that too, that Sbi had brought him generally in the direction Sbi wanted him to go.

XXIX

Waden Jenks: Do you know what frightens me most in the world, Herrin? Not dying. Discovering—that I’m solitary; that my mind is the greatest one, and that I’m damned to think things beyond expression, that I can never explain to any living being. Have you ever entertained such thoughts, Herrin?

Master Law: (Silence.)

Waden Jenks: I think you have, Herrin. And how do you answer them?

Colonel Olsen: The module’s come through; the station begins its construction. Now there’s a matter of the other agreements. Of supply. My aides will draw up a list of requirements.

Waden Jenks: Of no interest to me. Consult appropriate departments in the Residency.

Colonel Olsen: We find no cooperation in these departments of yours.

Waden Jenks: You intrude, colonel, we have our ways. You persist in coming in person. Use the liaisons we are training in University, that’s their purpose, after all.

Colonel Olsen: Nothing you’ve given us has been of value; not your information; not your promises of cooperation.

Waden Jenks: Yet you remain; you and I both know you are obtaining something you desire: a base. Supplies have become important to you. Let’s then admit that you want them badly and that it’s a matter for my personal attention; let’s adjust the price accordingly. Let’s talk about agreements that keep your bureaus from disturbing us. From setting foot here.

Colonel Olsen: We have policies....

Waden Jenks. They don’t get you what you want.

A ship passed in the night sky, a shuttle, headed offworld. Herrin watched it go, from the hills above Kierkegaard. He looked down on the city, with its dimly lighted streets, with the bright glare of the port like a bleeding wound. He felt Sbi’s presence at his elbow without needing to look. “Do you know what that was, Sbi?”

“One of the shuttles. I know. You taught us about other worlds.”

“Does it occur to you that we two don’t control everything?”

“Ah, Herrin, I understand more than that.”

“What more, Master Sbi?”

“That somewhere among those points of light stand others who misapprehend their limits; that somewhere at this moment someone is in pain; that somewhere a life has begun; that somewhere one has ended; I feel them all tonight.”

“I’m trying to feel them.”

“Somewhere,” said Sbi, “is someone else wrestling with dilemma. Somewhere is someone wondering the value of life itself. The universe is always asking questions.”

“Somewhere,” said Herrin, “someone is scared.”

“Beside you, Herrin Law.”

He turned and looked at the ahnit, who almost blended with the night, a shadow among shadows. A strange impulse possessed him, a melancholy; he opened his arms and embraced Sbi’s alien shape, gently, because contact hurt. He had done so in his life with his parents, with his sister when they were both small; with Keye when he made love; with Waden when Waden had a public gesture to make; with the workers when they helped him from the scaffolding ... only those times in his life had someone touched him; and with Sbi again it was different. Sbi embraced him very gently, and he stepped back and looked at Sbi sadly. “I don’t see you have any need to go down there.”

“Probably you don’t see,” Sbi said. “In some things you’re very complicated. Why did you go to your old house, Herrin Law, and to those people?”

“I don’t know.”

“A Master does something and confesses not to know why?”

“I wanted shelter. It didn’t quite work out, did it?” Heat came to his face. “I’ve made that mistake several times; it brought me here. Possibly it’s got hold of me again. Why else am I going down there? Stubbornness. I have some perverse desire to try it again, to talk to people I knew, to shake them till they see. I’m sure the Outsiders will see. I’m sure those who did this to me will.” He thought a moment. “I’m mad, aren’t I? Invisibles are. So why should you go?”

“Why did you go to your old house, and to those people?”

“Not satisfied with my answer?”

“No.”

He folded his arms across his ribs and stared at all the lights. “Well, it doesn’t make sense.”

And after a moment: “Why go, Sbi? Answer myquestions.”

“But this is what I’ve lived my life for.”

“What, ‘this’? What this?”

Sbi rested a hand on his shoulder. “That you give me back my faith. That I see our destroyers have the capacity to create. For one who believes in the whole universe, to one who doesn’t ... how can I explain?”

Herrin looked up at the sky above the city.

“We’ve become part of it again,” Sbi said.

“And if we all die, Sbi? Somewhere in your universe, somewhere out there—is there some world dying tonight?”

“Do you feel so?”

“O Sbi.” He shivered, and shook his head. And started down the slope, losing sight of the city among the hills.

Sbi overtook him, a soft pacing beside him in the grass, company in the dark.

“I don’t think,” Sbi said, “that the port market is likely to be open. The Outsiders were unfriendly to it. And without it—invisibles will go hungry; and some will pilfer in-town and some will trade for what those pilfer; and some who are ahnit will have gone away.”

“Best they should,” he said glumly. He considered what he should do, what there was to say ... to Waden Jenks.

Try reason again?He had no doubt that Waden could kill him. Likely there were Outsiders about who would never let him close enough to say anything at all. They walked among the hills a long while, back and forth among the troughs and through the sweet-smelling grass. He savored the time finally, for what it was, because of the grass and the smell and the sounds and the hills and the sky. And Sbi’s presence. That too.

Then he rounded the shoulder of a hill and had a limited view of the city again, faint jewels against the dark.

And some of them were red.

“Sbi?—Sbi, what do you make of that?”

“The port,” Sbi said.

“It’s not fire. It’s not that.” The lights flashed. There was a whole cluster of them. The unwonted sight disturbed him. It was an Outsider phenomenon. He recalled the shuttles which had lifted, more activity than Freedom had ever had from Outsiders. He thought of Waden, and increasingly he was afraid—for Waden, for Keye, for all of them down there who had started to disturb more than they knew how to see.

“Let mego to explore this thing,” Sbi said. “I know where to go, how to move and when to move. Let me go ask questions. Some of us will have seen this thing close at hand.”

“No,” he said at once, and started off again, hurrying. “No, we’re both going. I have a place to go, too, and questions to ask, and I know where to ask them.”

“A ship,” said Sbi. “Herrin Law, look, see it.”

Something was lifting from the port. He began to laugh, a breath of relief. “A launch, that’s all. Maybe it looks like that from up here.”

“No,” said Sbi. “I’ve seen, and it doesn’t.”

The ship climbed, shot off with blinking lights.

And exploded.

“Sbi!”

“I see,” the ahnit said.

The flower died in the heavens. Suddenly there were bursts on land, flares which curled up silent, firelit smoke that traced toward the city.

Herrin began to run, downhill. “Wait,” Sbi called to him, hastening after. Herrin ran, slid, slowed when his ribs shot pain through him and shortened his breath ... he walked then, because that was all he could do, and the bursts of fire continued, stitching their way through Kierkegaard.

“Waden’s Outsiders,” he mourned to Sbi. “Waden’s ambitions . . .”

XXX

Colonel Olsen: (by com) That’sSingularity. You’ll be gratified to know, First Citizen, that we’ve finally found McWilliams and his lot. So much for your information.

Waden Jenks: (by com)Do s omething.

Colonel Olsen: Oh, wegot him, First Citizen. That’s a certainty. Only how many others are there?

Waden Jenks: (Silence).

Colonel Olsen: First Citizen, what damage to landing facilities?

Waden Jenks: (Silence.)

There were fires, in the grass, a wall of fire which swept away to the sea, a curtain of red and orange two stories high that made black skeletons of trees and bushes and glared eerily in the water of the Camus.

There were fugitives, who straggled away from the city along the Camus-Kierkegaard road, and crossed the bridge over the firelit waters. Some were terribly burned, in shock; some, perhaps mad, had flung themselves into the river and drifted there, dark pinwheels in the red current.

“Stop,” Sbi pleaded, catching gently at Herrin’s cloak. “Stop and consider.”

Herrin did not, but wove his way across the concrete bridge of the Camus, past scarecrow figures headed away, past a cloaked figure who reached out hands and caught at his companion, telling Sbi something in urgent booms and hisses. Herrin delayed, wanting Sbi if Sbi wanted to stay with him—saw Sbi accept the other’s cloak and fling it on, bid the other some manner of farewell, but the other ahnit, naked of the cloak, stood staring as Sbi came away to go with him. “It’s bad in the city,” Sbi said. “Some of the buildings are afire.”

He had reckoned so. He thought of his work, vulnerable in the center of the city, and hastened along the paved highway. It occurred to him that another burst of fire could come down on them at any time. He looked up as they walked and saw nothing but the smoke, the stars obscured.

Breath failed him finally, where the road bent from the riverside, where the buildings began and he could see the city street-lights dark as they had never been, and fire. He saw the dome, distant from him, outlined against burning, and stood there, trying to get his wind. There were no fugitives here. He could see figures beyond, but those who were running for the highway had already run. Here, from this perspective up Main from the highway, there was only himself and Sbi, Sbi a reliable, comforting presence.

“Herrin,” Sbi said quietly. “Herrin, were they weapons and not some accident?”

“I think they were.” He drew a deep and painful breath. “Waden said ... of a certain man ... that he could level the city. It’s not so bad as leveled, Sbi, but it’s all gone wrong; and whatever I could do—it’s too late. Waden’s new allies haven’t helped. And I don’t think my people will want this reality.”

“They’ll see.”

“They’ll go mad. They’ll not survive this.”

“I thought,” said Sbi, “that ahnit had learned all the bitter things humans had to teach. I had not imagined this.”

“Come on. Come on, Sbi, or go back. This can’t be what you waited so long to find. Maybe I’d better go from here on my own.”

“No,” said Sbi, and stayed with him.

He walked slowly in the dark streets, deserted streets, with pebblestone and concrete buildings, faces all alike, eyeless black windows, open doors likewise black. Ahead of them a wall of flame burned in the city, outlining the dome and everything beyond. “It’s the hedge,” Herrin realized suddenly. “The hedge is burning, up by the Residency, the University. ...”

So was a building close to them, somewhere near First and Main, beyond, the dome, a steady spiral of firelit smoke. A warehouse, perhaps, or something more tragic: apartments were everywhere.

The dome was before them. Fire showed through the perforations here and there like tears of light. There was, even here, a wound, a fall of broken stone where the outermost shell of the dome was damaged. Herrin saw it and ached, walking across the paving and up to the entry and within.

People huddled here, citizens, invisibles ... there was no telling in the deep shadow; the dome had become a shelter. Children wept, setting off bell-like echoes, a cacophony of mourning and sad voices. Herrin walked through, and Sbi with him, past the outer, triple shell and the curtain-walls, into the central dome, where the face of Waden Jenks survived untouched. Fire provided the light through the perforations now, dim and baleful, and cast the features into torment.

Herrin shut his eyes from the sight, looked back at Sbi’s hooded form, saw beyond him dark masses of refugees. His own workers would be among them. If anyone would have come here, they would have come, as they always had. Fearfully he lifted his clumsy hands, pushed back his hood, knowing well the enormity of what he was doing; but they had seen far worse tonight than an invisible’s face.

“Gytha,” he called out, setting off sharp echoes which shocked much of the other echo into silence. “Phelps?” And because he committed other unthinkable things: “Pace? Are you here?”

Master Law, some voice said, somewhere in the dome. There was a flood of echoes, other voices whispering it, and one calling it out... “Master Law!”

People came to him, some that he knew, some that he did not, and suddenly he panicked, because in the dark there was no color, and he had deceived them. They came, and near him Sbi stood, still hooded. Someone tried to take his hand, and he flinched and saved himself, looked into Carl Gytha’s tear-streaked face and flung his arms about him, which hurt too. He could not make himself heard if he tried: the whole dome rang with voices. Master Law!the shout went up, and people surged in until they pressed on him and Gytha and someone thrust at the crowd trying to clear him room.

“Let me out,” he pleaded of Gytha, of Sbi, of anyone who could hear him. He shouted into the noise and could hardly hear himself. “Let me out!” The whole place was mad and Waden Jenks’s firelit face presided over it in rigid horror.

Perhaps Gytha understood. A tide started in the press which surged toward the other side of the dome, which swept him along with Gytha’s arm to protect him ... or Sbi’s ... in the confusion he was no longer sure. The crush compressed his ribs, threatened his hands, and he would have fallen but for an arm which encircled his waist and pulled him.

They broke forth into the air, a spill of the crowd like a wound bleeding forth onto the firelit paving. He had a momentary view of the distant, dying fires of the hedge, of ancient shrubbery gone skeletal and black as winter twigs.

“Sir,” someone was saying to him, but he shook his head dazedly, finding even breathing hard. The crowd was pouring out after him, threatening to surround him here as well. Panic took him and he pushed at someone with his arm, saw Gytha’s anxious look directed to the outpouring crowd.

And there in shadow, a taller, hooded figure, which unhooded itself and stood with naked head facing the crowd, which wavered, which slowed. Sbi turned and purposefully came and took him by the arm, drew him away in the moment’s shock, even away from Gytha, even from those he would have wanted to see. He yielded to Sbi’s encircling arm, walking farther up Main, slipping into what fitful shadows there were from the light of the burning, where Second Street offered them shelter.

Herrin stopped there, sank down on the doorstep of a dark and open doorway, his arm locked across his aching side.

“You are hurt?” Sbi asked him, touched his face with two gentle fingers, wiped sweat from him.

“Drink?” Herrin asked, for shock threatened him and somewhere—he could not even remember where—he had lost the bundles of his belongings, everything. Sbi bent and touched his lips, transferred a mouthful of sweetish fluid to him, caressed his brow in drawing away and regarded him with great black eyes, pursed mouth bearing an expression of ahnit sorrow.

“Sit,” Sbi wished him. “O Herrin, sit still.”

“Waden,” he said. “He and Keye ... won’t know what to do. Can’t know what to do. I have to go to the Residency, Sbi, and talk to them ... if I can help there—I have to.”

He tried to get up. Sbi did not help him at first, until he had almost made it and almost fallen, and then Sbi’s arm encircled him. A dark runner passed them, slowed, looked back and ran on, quick steps fading. Soon there were others, straggling after. Sbi’s arm tightened protectively. “I don’t trust this, Herrin.”

“Come on. Come on. Let’s get back to Main, into the light.”

“Your species frightens me.”

“Come.” He walked, insisting, anxious himself until they were back on the main line of the city, with the smoldering hedge in front of them and the fire from the burning buildings still lighting the smoke which hung over the city like a reddened ceiling, casting light to all that was below it. It all looked wrong; and then he realized that he had never seen the buildings on Port Street without the façades lit. Only a few windows showed light on the Residency’s uppermost floor. He could not see the University clearly, but they had emergency power over there too, as they did at the port, and it was all dark, as far as he could see.

He was afraid ... on all sides, afraid. More runners passed them, one screaming: he thought it screamed his name, and flinched. Back at the dome they were still shouting, still in uproar, and the echoes made it like the voice of some vast single beast.

They left the concrete for the berm, which was powdered black with the burning of the hedge. Smoke obscured their vision. Fires still crackled, knee-high flames in a line down the remnant of the hedge on either side as they passed what was left of the archway and crossed onto Port Street, in front of the Residency.

The whole west end was a shambles, the roof of the fifth level caved in, making rubble of that level and the next, where he had had his rooms ... and cracking walls beneath. The east wing, the source of the lights, stayed apparently intact, but the cracks ran there too.

I would have died here,he thought dazedly, reckoning where his rooms were. He crossed the street with Sbi close beside him. No one prevented them, no one appeared on the street or on the outside steps. The doors gaped dark and open, showing only a little light from somewhere up the interior stairs when they walked in. The desk at the entry was deserted, dusted with fallen cement and there was rubble on the floor.

“Waden?”he called aloud, and his voice echoed terrifyingly in the empty halls. Something moved, scurried, ran, stopped running in some new hiding. The skin prickled on his nape, and he felt the touch of Sbi’s hand at his arm as if Sbi too were insecure. He started up the stairs, careful in the shadows and the litter of rubble. Sbi imprudently put a hand on the wooden railing and it tottered and creaked.

They came into the uppermost hall, where light showed on the right and wind from the ruined west wing came skirling in with a stinging breath of smoke. “Waden?” Herrin called again, fearing to surprise whatever guards Waden Jenks might have about him. He trod the hall carefully, toward that closed door where Waden’s office was.

He called again. Something moved inside. He heard a voice, used his bandaged hand to press the latch and pushed it open.

Keye met them. She had been sitting opposite the door in the long room, and rose, and her hands came up to shield her face. She cried out: Keye ...cried aloud, and Herrin reached out a hand to prevent her dissolution. “Keye,” he said, but she darted—for him, he thought for the instant—and then slid past him, past Sbi, for the dark hall, out, out of his presence and the sight of him. He looked back again to the room, dazed and of half a mind to go after Keye, to stop her if he could and reason with her if there was any reason. But there was movement in the doorway beyond the ell, and Waden was there, his face quickly taking on that look that Keye’s had had.

“Waden,” Herrin said, before he could do what Keye had done. “What happened?”

Waden only stared at him, in frozen stillness.

“The Outsiders,” Herrin said. “Waden, you see me. You see I’m not alone; you always have, haven’t you? Wake up and see what’s going on, Waden. The city’s afire; your Outsiders have run mad. It was a lie. From the beginning, everything University set up—was a lie.”

“Your reality,” Waden said from dry lips. “This is your reality, Herrin Law.”

He blinked, caught up in that fancy automatically, for one mind-wrenching instant that made all the walls shimmer, that rearranged everything and sent it inside out. “No,” he said, and reached his clumsy hand for Sbi, for a blue cloak, drawing the ahnit forward, into Waden’s full view. “Real as I am, Waden; real as you are, as the fire is real. You can’t cancel it.”

“It’s yours,” Waden said bleakly. “I would not have imagined this. I failed to kill you, and you did this.”

“You’re mad,” Herrin said. “ Idid this? I did nothing of it. It was your doing, from the first time you brought them here. What ship attacked us? Was it Singularity? Or your own allies?”

“Whatever you imagine,” Waden said. It was a lost voice, a lost look in his eyes, which spilled tears. “I should have had them finish you; I neededyou. That should have warned me where control was ... really. O Herrin, your revenge is excessive. Remake it. Revise it.”

It was an ugly thing to see, a hurtful thing. He closed his eyes to it and looked again, saw Waden still standing there, hands open, face vulnerable. “I wish I could, Waden. But you see—” He sought, half humorous, some logic to devastate logic, to break through to Waden Jenks. “—I let it go. The reality I imagined was a reality that would become universal, that would exist on its own in time and space ... that I myself could no longer interrupt, that’swhat I imagined. And now the world has to take its course under those terms. Sbi exists. We’ll all see each other. We’ll listen to the ahnit and see them. We’ll not do things the way they were; we’ll not teach dialectic to shut down minds; we’ll not bewhat we were. And I can’t stop it. That’s what I imagined.”

Waden’s eyes were terrible. Not vacant but following that speculation, gazing into possibilities. “What do you imagine that I’lldo?”

“I imagine ... that you’ll do things that are natural to this reality. Whatever they are. I can’t stop it. You can’t. We have no more control, Waden. Nor do the ahnit. We share this world and it comes down to that. It has its own momentum and it can’t be canceled.”

Waden turned away, fending himself from the door frame, walked back into the dark.

“Waden,” Herrin objected.

“You created paradox.” Waden’s voice came back out of the dark. “And you abdicated. You’ve done this, Herrin Law, you’ve done this.”

Herrin started forward, to go in, but Sbi’s arm intervened. “No,” Sbi said. “No, don’t go in there. Come with me. Please, come away from this place. Now.”