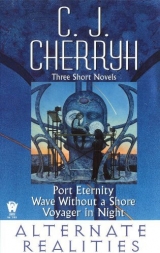

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

IX

In love, if love be love, if love be ours,

Faith and unfaith can ne’er be equal powers:

Unfaith in aught is want of faith in all.

We fled into the crew quarters, Gawain and Modred, Vivien and I ... quietly as we could, but Lynn and Percy lifted their heads from their pillows all the same. We started taking off boots, settling down for a little rest.

“Where’s Lance?” Gawain asked, all innocent.

“Dela called,” I said, from my cot where I had lain down next Lance’s vacant one; and Gawain’s face took on an instant apprehension of things. Viv looked up from taking off her stockings. I closed my eyes and folded my hands on my middle, uncommunicative, trying to shut out the sound from the hull. It was down to a familiar pattern now ... tap-tap-tap. It grew fainter. I thought of the tubes like branching arteries. Maybe they were working somewhere farther up, at some branching. I imagined such a thing growing over the Maid, a basketry of veins, wrapping us about. I shuddered and tried to think of something pleasant. About the dinner table with the artificial candles aglow up and down it, dark wood set with lace and crystal and loaded with fine food and wines. I would like a glass right now, I thought. There were times when I would have gone to the gallery and stolen a bottle. I didn’t feel I should. Share and share alike, my lady had said; and the good wine was a thing we would run out of.

Supposing we lasted long enough.

There was silence. I opened my eyes.

“It stopped,” Percy said, very hushed.

“Whatever they’re doing,” Modred said, “they’ll have it done sooner or later. I’m only surprised it’s taken this long.”

“Stop it,” Vivien said, very sharp, sitting upright on her bed, and I rolled over to face them, distressed by Viv’s temper. “If you’d done your jobs,” Viv said, “we wouldn’t be in this mess. And if you did something instead of sit and talk about it we might get out.”

“Someone,” Lynn said, “might go out on the hull with a cutter.”

“In that?” Percy asked. That was my thought; my stomach heaved at the idea.

“I could try it,” Lynn said.

“You’re valuable,” Modred said. “The gain would be short term and the risk is out of proportion to the gain.”

Like that: Modred’s voice never varied ... like Viv’s sums and accounts. I had had another way of putting it all dammed up behind my teeth. But the crew wasn’t my business, any more than it was Viv’s.

“What are you going to do?” Viv asked. “What are you doing about this thing? Our lady depends on you to do something.”

“Let them be,” I said, and Viv looked at me, at me, Elaine, who did my lady’s hair and had no authority to talk to Vivien. “If it was your job to run the ship you could tell them what to do, but they’ve done everything right so far or we’d none of us be alive.”

“They left us grappled to this thing. Was thatright? They talkedto that thing instead of breaking us loose on the instant. Was that right?”

“Grappling on,” Modred said, unstoppable in locating an inaccuracy, “was correct. We would have damaged the hull had we kept drifting.”

“And talking to it?”

“Let them be,” I said, because that argument had bit them: I saw that it had. “Maybe it was right to do. Wasn’t that our lady’s to decide, and didn’t she?”

“Griffin,”Viv said. “Griffin decides things. And he wouldn’t be deciding them if the crew’s incompetency hadn’t dropped us into this. We were in the middle of the system. You can’t jump from the middle of the system. And they did it to us, getting us into this.”

“We were pulled in,” Gawain said. “There wasn’t any warning. No evasion possible.”

“For you. Maybe if you were competent there’d have been another answer.”

That was Vivien at her old self again: she did it in the house at Brahmani Dali and sent some of the servants into blank. Now she tried it on the crew. I sat up, shivering inside. “Maybe if Viv’s hydroponics don’t work out, shecan go out on the hull,” I said. It was cruel. Deliberately. It left me shivering worse than ever, all my psych-sets in disarray. But it shut Viv down. Her face went white. “I think,” I said between waves of nausea my psych-sets gave me, “you’ve done all the right things. So it breaks through. It would do it anyway; and so you’ve talked to it: would it be different if we hadn’t? And so it’s got us; would we be better off if we’d slid around over the surface until we made a dozen holes it could get in, and it grappled us anyway?”

They looked at me like so many flowers to the sun. Percy and Gawain and Lynn looked grateful. “No,” Modred said neatly, “the situation would be much the same.”

Viv could scare them. She could scare anyone. She had my lady’s ear ... at least she had had it when she did the accounts; and she had that reputation. But so did I have Dela’s ear. And I would say things if Vivien did. I had that much courage. Dela’s temper could makethe crew make mistakes. She could order them to do things that might endanger all of us. She could order Lynn out on the hull. Or other dangerous things.

“We’re supposed to be resting,” I said. “It’s against orders to be disturbing the crew.”

“Oh. Orders,” Viv said. “Orders ... from someone who skulks about stealing. I know who gets tapes they’re not supposed to have. Born-man tapes. I suppose you think that gives you license to tell us all how it is.”

“They might do you good. Imagination, Viv. Not everything comes in sums.”

That capped it. I saw the look she gave me. O misery, I thought. We don’t hate like born-men, perhaps, but we know about protecting ourselves. And perhaps she couldn’t harm me: her psych-set would stop that. But she would undermine me at the first chance. I was never good at that kind of politics. But Viv was.

It didn’t help my sleep. I was licensed to have that tape, I thought; I was justified. My lady knew, at least in general, that I pilfered the library. It was all tacit. But if Vivien made an issue, got that cut off—

I had something else to be scared of, though I persuaded myself it was all empty. Bluff and bluster. Viv could not go at that angle; knew already it would never work.

But she would suggest me for every miserable duty my lady thought of. She would do that, beyond a doubt.

The hammering started up again, tap, tap, tap, and that hardly helped my peace of mind either. We quarreled over blame, and itmeanwhile just worked away. I rolled my eyes at the ceiling, shut them with a deliberate effort.

Everyone settled down then, even Vivien, but I reckoned there was not much sleeping done, but perhaps by Modred, who lacked nerves as he lacked sex.

I drowsed a little finally, on and off between the hammerings. And eventually Lance came back—quietly, respecting our supposed sleep, not brightening the lights. He went to his locker, undressed, went to the bath, and when he had come back in his robe he lay down on his bed next to me and stared at the ceiling.

I turned over to face him. He turned his head and looked at me. The pain was gone. It could not then have gone so badly; and that hurt, in some vague way, atop everything else.

I got up and came around and sat on the side of his bed. He gave me his hand and squeezed my fingers, seeming more at peace with himself than he had been. “I was not,” he said, “what I was, but I was all right. I was all right, Elaine.”

Someone else stirred; his eyes went to that. I bent down and kissed him on the brow, and his eyes came back to me. His hand pressed mine again, innocent of his difficulties.

“Griffin knows,” I warned him. I don’t know why it slipped out then, then of all times, when it could have waited, but my mind was full of Griffin and dangers and all our troubles, and it just spilled. He looked up at me with his eyes suddenly full of shock. And hurt. I shivered, that I had done such a thing, hurt someone for the second time, and this time in the haste of the hour.

“They quarreled,” I said, walking deeper into it. “Lance, we’re supposed to help him ... you understand ... with the ship. Lady Dela says so. That we’re to help. She’s afraid, and there’s something going on—” The hammering stopped again. This time the silence oppressed me, and a cold breeze from the vents poured over my skin. I put my hands on Lance’s sides, and he put his on my shoulders, for comfort. There was dread in his face now, like a contagion. “Bridges,” I said. “Whatever-it-is means to use a Bridge to get to us. All the other ships ... have tubes going in and out of them. They’ve seen it ... the crew ... when they fined down the pictures on the bridge. That’s what that hammering is out there.”

He absorbed that a moment, saying nothing.

“Lady Dela’s not to know yet,” I said. “Griffin doesn’t want to frighten her.”

Lance nodded slightly. “I understand that.” He lay there thinking and staring through me, and what his thoughts were I tried to guess—I reckoned they moved somewhere between what was working at us out there and what small happiness I had destroyed for him.

“What are we going to do about it?” he asked finally.

“We’re supposed to be back up on the bridge at 1000. All of us. I think Griffin’s got something in mind. I hope so.”

“It’s after 0800, isn’t it?”

I turned around and looked at the clock. It was 0836. “I think I should have gotten everybody breakfast. There’s still time.”

“I don’t want it. Others might.”

“Lance, you should. Please, you should.”

He stayed quiet a moment, then got up on his elbow. “You go start it, I’ll come and help.”

I got up and started throwing on my clothes again. There was time, indeed there was time; and it was on my shoulders, to see that everyone was fed. Everyone would think of it soon, and maybe our spirits wanted that, even if our stomachs were not so willing.

It took all kinds of strength to face that thing out there, and in my mind, schedules were part of it, insisting that our world went on.

But I kept thinking all the while I rode the lift down to the galley and especially before Lance came to help me, that it was very lonely down there. The hammering was stopped now; and I was in the outermost shell of the Maid, so that the void was out there, just one level under my feet while I was making plates of toast and cups of coffee. I felt like I had when I had first to walk the invisible floor and teach my eyes to see—that maybe our Beast didn’t see things at all the way our senses did, and maybe it just looked through us whenever it wanted, part and parcel of the chaos-stuff.

Lance came, patted me on the shoulder and picked up the ready trays to take them where they had to go. “I’ll take those topside,” I said purposefully, meaning Dela, meaning Griffin; and I took them away from him.

He said nothing to that. Possibly he was grateful. Possibly his mind was somewhere else entirely now, on the ship, and not on Dela; but I doubted that: his psych-set didn’t make that likely.

Dela was abed, where I looked to find her. She stirred when I touched her bare shoulder, and poked her head up through a curtain of blonde hair, pushing it back to discover breakfast. “Oh,” she said, not sounding displeased. She turned over and plumped the pillows up to take it in bed. ‘Is everything all right then? It’s quiet.”’

“I think it’s given up for a while,” I lied, straight-faced and cheerfully. “I’m taking breakfasts round. May I go?”

“Go.” She waved a dismissing hand, and I went.

Griffin I found asleep too—all bent over his desk in his quarters, the comp unit still going, the papers strewn under him on the surface. “Sir,” I said, tray in hand, not touching him: I was wary of Griffin. “Sir.”

He lifted his head then, and saw me; and his eyes looked his want of sleep. I set the tray down for him and uncovered it, uncapped the coffee and gave that into his hands.

“It’s stopped,” he said.

I nodded. “Yes, sir, off and on. It’s been quiet about half an hour so far. It’s 0935, sir.”

He turned with a frown and dug into the marmalade. I took that for a dismissal on this occasion and started away.

“Have you slept, Elaine?”

I stopped. “Much as I could, sir.”

“The others?”

“Much as they could, sir.” My heart started pounding for fear he would ask about Lance or discuss my lady, and I didn’t want that. “They’ll be eating now. They’ll be on the bridge soon.”

He nodded and ate his breakfast

So we came topside at the appointed time, to the bridge. The crew took their posts; Lance and Viv and I stood. The quiet about the hull continued, the longest lapse in hours. And that quiet might mean anything ... that whatever-it-was had finished out there, that the Bridge was built and we had very little time ... or that it really had given up. But none of us believed the latter.

1005. Griffin delayed, and we waited patiently, no one saying anything about the delay, because a born-man could do what he liked when he had set the schedule. Viv found herself a place on the cushion by the door, alone, because I wasn’t about to sit by her; and Lance stood by me.

“Nothing more has come in,” Modred said after checking the records from the night. “Everything’s as it was.”

Transmissions, he meant. All around us the screens showed the old images, the unrefined images, just the glare and the light, the slow creep of measled red and black shading off to purples and greens.

There were footsteps in the corridor outside. Griffin arrived, and Dela was with him, in her lacy nightclothes, her hair twisted up and pinned the way she would do when I wasn’t convenient to do it in its braids.

She looked us all up and down, and looked round the bridge, and Viv and the crew rose from their places and stood respectfully—as if she had just come aboard, as if she had just come here for the first time. As if—I don’t know why. Neither, perhaps, did the others, only it was a respect, a kind of tenderness.

She looked around a moment at things I knew she couldn’t read, at instruments she didn’t know, at screens that showed only bad news, but not the worst. And she kept her hands clasped in front of her, fingers locked, and looked again at all of us. All of us. And Lance: her eyes lingered on him; and then on Gawain. “Griffin has talked to me,” she said after a moment. “And he wants to fight this thing, whatever it is. And he wants you to help him. You have to. I see that ... that if it tries to get in, someday it’s going to. And that means fighting it. Do you think you can?”

We nodded, all of us. We had no real compunction about it, at least I didn’t, small damage that I could do anything because it threatened our lady; and it wasn’t its feelings we were asked to hurt.

“You do that,” Dela said, and walked away.

And out the door, past Viv. Very small and sad, and frightened.

I wanted to run after her; I looked at Griffin instead, because we had our orders, and on Griffin’s face too there was such an expression of pain for our lady—I looked at Lance, and it was the same. And Gawain and Percy and Lynn. Only Vivien scowled; and Modred had no expression at all.

Griffin made a move of his hand, walked to the counter where he could face all of us at once. “Here it is,” Griffin said. “They aregoing to get in. Maybe they’ll come in suits and blow our lifesupport entirely, and rearrange it all, because they need something else. They could be some other ship who’s trying to survive here and doesn’t mind killing us. But I don’t think so. The tunnels are general; they’re everywhere. And that points to the wheel itself. The station. Whatever it is we’re attached to. I’ve talked to Dela about it. There’s no gun aboard; but we’re going to have to set up some kind of a defense. If they blow one compartment, we can seal it off, so we’ll just redraw the line of defense. But they’re going at it so slowly ... I think it’s more deliberate than that. They’ve done it—to all the ships. And maybe time isn’t important to it. To them. Whatever.” He looked from one to the other of us. “What we can’t have is someone panicking and blanking out at the wrong time. If you don’t think you canfight, tell me now. Even if you’re not sure.”

No one spoke.

“Can you, then?” he asked.

“We’re high order,” Gawain said, “and we don’t tend to panic, sir. We haven’t yet.”

“You haven’t had to kill anything. You haven’t come under attack.”

That posed things to think about.

“We can,” Lynette said.

Griffin nodded. “You find weapons,” he said. “Cutting torches and anything that could do damage. Knives. If any of those decorations in the dining hall have sound metal in them—those. Whatever we’ve got that can keep something a little farther away from us.”

So we went, scouring the ship.

X

... but in all the listening eyes

Of these tall knights, that ranged about the throne,

Clear honor shining like the dewy star

Of dawn, and faith in their great King, with pure

Affection, and the light of victory,

And glory gain’d, and evermore to gain.

It was one of those longdays. We scoured about the ship in paranoid fancy, cataloguing this and that item that might be sufficiently deadly.

Of course, the galley. That place proved full of horrors.

And the machine shop, I reckoned: the crew spent a long time down there making lists.

And of course the weapons in the dining hall and Dela’s rooms. They were real. And it was time to take them down.

That was Viv and I. I stood on the chairs and unscrewed brackets and braces while Viv criticized the operation and received the spears and the swords below. And my lady sat abed, so that I earnestly tried to muffle any rattle of metal against the woodwork, moving very slowly when I would turn and hand a piece to Viv, who was likewise quiet setting it down.

I thought about the banners, whether we should have them; the great red and blue and gold lion; the bright yellow one with green moons; the blue one with the white tree; and all the others. And I thought of the stories, and it seemed important, if we had the one we should have the other—at least the lion, that was so gaudy brave.

“That’s not part of it,” Vivien said when I attacked the braces.

“Oh, but it is,” I said. I knew. And Viv stood there scowling. I handed it toward her.

“It’s stupid. It doesn’t do anything.”

“Just take it.”

“I’m not under your orders.”

“Quiet.”

“ Who’squiet? Put that back and get down off the chair.”

“I’m not going to put it back. At least get out of my way so I can get down.”

“Elaine?”

Dela’s voice. “See?” I said. It was stupid, the whole business. I turned the cumbersome standard with its pole so that I could gather the banner to me, and stepped down from the chair, having almost to step on Viv. We can be petty. That too. And Viv was. Too good for menial work. It was me my lady called and we don’t call out loud like born-men, shouting from place to place. I hurried across to the bedroom door and through, with my silly banner still clutched to me and all the while I expected Viv was right.

“Elaine, what’s that you’ve got?” My lady sat abed among her lace pillows, all cream lace herself, and blue ribbons.

“The lion, lady.”

“For what?” my lady asked.

“I thought it should make us braver.”

A moment Dela looked at all of me, my silly notions, my other self, thatElaine. Her eyes went strange and gentle all at once. “Oh my Elaine,” she said. “Oh child—”

No one had ever called me that. It was only in the tapes. “Lady,” I said very small. “Shall I put it back?”

“No. No.” Dela flung off the covers, a flurry of lace and ribbons, and crossed the floor; I stepped aside, and she went through into the sitting room, where we had made a heap of the weapons, where Viv stood. And she bent down all in her nightthings and gathered up the prettiest of the swords. “Where are these to go?” She was crying, our lady, just a discreet tremor of the lips. I just stood there a heartbeat, still holding the lion in my arms.

“Out to the dining hall,” I said. “Master Griffin said we should bring all the things there because it was a big place and central so—”

–so it wouldn’t get to our weapons store when it got in; that was the way Griffin put it. But I bit that back.

“Let’s go, then,” said Dela.

“Lady,” Vivien said, shocked. But Dela nodded toward the door.

“Now,” Dela said, taking up another of the swords and another, and leaving Vivien to gather up the heavy things. Me, I had the lion banner, and that was an armful. Dela headed out the door and I followed my lace-and-ribboned lady—not without a look back at Vivien, who was sulking and loading her arms with spears and swords.

So we came into the dining hall turned armory, and I unfurled the lion and set him conspicuously in the center of the wall, to preside over all our preparations. There was kitchen cutlery and there were pipes and hammers and cutters, and the makings of more terrible things, in separate containers—

“What are those?” Dela asked.

I had no wish to answer, but I was asked. “Chemicals. Gawain says we can put them in pipes and they’ll blow up.”

Dela’s face went strange. “With us in here?”

“I think they mean to carry them down to the bow and not make them up till then. They’re working down there—Master Griffin and the others. They don’t mean they should get through at all.”

“What else is there to do?”

I thought then that she wantedsomething. I understood that. I wanted to work myself, to work until there was no time to think about what was going on outside. From time to time the hammering stopped out there and then started again. And I dreaded the time that it would stop for good, announcing that they/it/our Beast might be ready for us. “There’s all of that to carry and more lists to make; we’re supposed to know where all the weapons are; and food to make and to store in here and the refrigeration to set up—in the case,” I finished lamely, “we should lose the lower deck.”

Viv had arrived, struggling with her load, and dumped it all. “Careful,” my lady said sharply, and Viv’s head came up—all bland, our Viv, but that was the face she gave my lady.

“And they’re welding down below,” I finished. “They’re cutting panels and welding them in, so if they think they’ve gotten through the hull, they’ve only got as much to go again.

“We should all help,” my lady concluded. “All.”

“I have my work upstairs,” Viv said; she could get away with that often enough, could Viv. I have my books; I have accounts to do; and Go do that, my lady would say.

Not now. “You can help at this,” my lady said, very sharp and frowning. “Make yourself useful. You’re not indispensable up there.”

Oh, that stung. “Yes, lady,” Vivien said, and lowered her head.

“I’ll get the rest of the weapons,” I offered.

“No,” my lady said, “Vivien can start with that. Get the galley things in order.”

“Yes,” I said. It was no prize, that duty, but it was the one I well understood.

“I’ll be down to help,” my lady said.

“Yes, lady,” I murmured, astonished at the thought, and thinking that I would have one more duty to care for, which was Dela herself, who really wanted to be comforted. I left, passed Vivien on my way out the door and hurried on to the lift, wiping my hands on my coveralls.

I took the lift down. The ship resounded down there not alone with the crashes and thumps of the thing outside, but with the sounds of Griffin and the others working, trying to put a brace between ourselves and the outside.

The galley was close enough to hear that, constantly, and it reminded me like a pulsebeat how the time was slipping away, and how we had so little time and they had all the time that ever might be in this dreadful place.

Other ships must have fought back. Nothing we had seen gave us any true hope. But I went about the galley reckoning how we could store water—we have to have water in containers, Griffin had said, because they might find a way to cut us off from the tanks. And we have to have the oxygen up there; the tanks and the suits. The whole ship had to be replanned. We had to think like those would think who wanted to kill us; and I was never trained for such things—except in my dreams. I set my mind to devious things, and reckoned that we must take all the knives and dangerous things out; and my lady’s good silver too, because they should not have that, nor the crystal. And all our medical supplies must come up.

And the portable refrigeration. That came first. We had it in the pantry, and I got down with a pliers I had from upstairs, and on my hands and knees I worked the bottom transit braces loose. Then I climbed up on the counter and attacked the upper braces.

So Dela found me, sweating and panting and having barked my fingers more than once—but I had gotten it free. “Elaine, call Percy,” she said: it was always Percy we called for things like this.

“Lady, Percy’s helping Master Griffin. They all are. I can manage.”

My lady looked at it uncertainly; but when I pushed from the back she wrestled it from the front, and the two of us got it out. I looked at her after, Dela panting with maybe the first work but sport she had ever done; her eyes were bright and her face flushed. “To the lift?” she asked.

I nodded, dazed. And she set her hands to it, so there was nothing to do but push ... through the galley and over the rough spot of the seal track, down the corridor toward the lift. And all the while that frenetic banging away toward the bow of the ship, toward which Dela turned her head distractedly now and again as we pushed the unit up to the lift door. But she said nothing of it.

We took it up; we wrestled it down the corridors and over section seal tracks and into the dining hall pantry where we decided was the best place to put it. “We have to brace it again,” I said. It was too heavy to have rolling about if the ship should shift or the like. So my lady and I contrived to get it hooked up and then to get it fastened into a pair of bottom braces.

And we sat there in the floor, my lady and I, and looked at each other. She reached over and put a hand behind my neck, hugged me with a strange fervor; but I understood: it was good to work, to do something together when it was so easy to feel alone in that dinning against our hull, and in our smallness against thatoutside.

We got up then, because there was the food to fetch up, and the water tanks. It was down again in the lift, and filling carts with frozen food and taking it up again; and hunting the tanks out of storage.

“The good wine,” Dela said. “We should save that.”

“And the coffee,” I said. My knees were shaking with all this pushing and climbing and carrying. I wiped my face and felt grit. “My lady, I think everyone might like to have something to eat.”

She thought about that and nodded. “Do that,” she said. “We can take something to Griffin.”

“I can do that,” I said, thinking how grim it was forward, where they were building our defenses.

But Dela was determined. So I made up as many lunches as I knew there were workers forward, which was everyone but Vivien; and we took the trays into that territory of welding stench and hammering, where the crew and Lance worked with Griffin.

They stopped their work, where the hallway had suddenly shortened itself in a new welded bulkhead improvised of a section seal and some braces. They were scorched and hot—the temperature here was far too high for comfort. And eyes widened at the sight of Dela: people stood up from their work in shock, Griffin not least of them, and took the trays Dela brought, and looked at her in a way that showed he was sad and pleased at once.

“We’ve got a lot of the upstairs work done,” Dela said, “Elaine and I.”

Griffin kissed her: we had washed, my lady and I, and were more palatable than they—a tender gesture, and then the They across the division boomed out with a great hammering that made us all flinch, even Griffin. “No need for you to stay here,” Griffin said.

But my lady took a tray and sat right down on the floor, and I did; so all the rest settled with theirs. I saw the crew dart furtive disturbed glances Dela’s way: she shook their world, and even Modred, who was too close-clipped to be disheveled ever, still looked disarranged, sweating as we all began to, and with exhaustion making lines about his eyes. Percy had hurt his hand, an ugly burn; and Gawain had his beautiful hair tied back in a halfhearted braid, and some of it flying about his face; and Lynette, close-clipped as Modred, had her freckled face drowned in sweat that gathered at the tip of her nose and in the channels of her eyes. Lance—Lance looked so tired, never lifting his eyes, but eating his sandwich and drinking with hardly a glance at us ... or at Dela sitting next to Griffin.

“We’re going to make braces for sealing more than one point in the ship,” Griffin said. “Lower deck; and the middecks. If they get to top—they’ve got everything. Only the topmost deck and the hydroponics ... we draw our final defense around that, if it has to be.”

“One of us might still go out there,” Lynette said. “Might still try to see what they’re up to.”

“No,” Griffin said.

“We could try.” Lance lifted his head for the first time. “Lady Dela, if one of us went out and tried to get into the thing—”

“No,” Dela said, with finality.

“They could learn us,” Griffin said. “It’s not a good idea. With one of us in their hands.... No. We can’t afford that. But we’ll see; it’s possible—they have rescue in mind. One can hope that.”

It was a thought to cherish. But I remembered that voice on the com, and how little it was like us. And the ships, pierced by the tubes like veins, bleeding light through their wounds.

Perhaps everyone else thought of that. The surmise generated no cheer at all, not even from my lady.

And time, as time did in this place, weighed heavy on us, so that it felt as if we had been all day at work instead of only half. Maybe it was the battering at our hull, that went on and on; and maybe it was a slow ebbing of the hope that we tricked ourselves with, that wrung so much struggle out of us, when a little thought on the scale of things was sufficient to persuade us we were hopeless.

I longed for the plains of my dreams, I did, and the horns blowing and the beautiful colors and the fine brave horses Brahman had never seen. But here we sat dirty and scorched with the welding heat and with the hammering battering at our minds; and never room or chance for a good run at our Beast. I looked up at Lance, wondering if he longed the same. I saw his eyes lifted that once, but it was a furtive glance toward Dela with all that pain on his face that might have been exhaustion. Might have been. Was not.