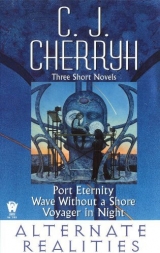

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 34 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

XXIII

Student: What if Others existed?

Master Law: Have they relevancy?

Student: Not to man.

Master Law: What if man weretheir dream?

Student: Sir?

Master Law: How would you know?

Student: (Silence.)

There was a long time that he shut his eyes and yielded to the motion, and passed more and more deeply into insensibility, jolted out of it occasionally when some stitch of pain grew sharp. Then he would twist his body to ease it, faint and febrile effort, and the ahnit would shift him in its arms, seldom so much as breaking stride. Most of all he could not bear to have his hands dangle free, with the blood swelling in them, with the least brush at the swollen skin turned to agony. He turned to keep them tucked crossed on his chest and thus secure from further hurt. He trusted the steadiness of the arms which held him and the thin legs which strode almost constantly uphill. It was all dark to him. He was lost, without orientation; the river lay behind them—there was no memory of crossing the only bridge but his memory was full of gaps and he could not remember what direction they had been facing when the ahnit had pointed toward the hills. Acrossthe river, he had thought; and up the river; but then he had not remembered the bridge, and he trusted nothing that he remembered.

They climbed and the climb grew steeper and steeper. Grass whispered. The breeze would have been cold if not for the ahnit’s own warmth. We shall stop soon, he thought, reckoning that it had him now within its own country, and that it would be content.

But it kept going, and he had time for renewed fear, that it was, after all, mad, and that he was utterly lost, not knowing back from forward. In time exhaustion claimed him again and he had another dark space.

He wakened falling, and flailed wildly, hit his hand on an arm and cried out with surprised misery. His back touched earth gently, and the ahnit’s strong arms let him the rest of the way down, knelt above him to touch his face and bend above him. “Rest,” it said.

He slept, and wakened with the sun in his face. Waked alone, and with nothing but grass and hills about him and a rising panic at solitude. He levered himself up, squeezing tears of pain from his eyes, broken ribs aching, and his hands ... at every change in elevation of his head he came close to passing out. Standing up was a calculated risk. He took it, swayed on his braced legs and tried to see where he was, but there were hills in all directions.

“Ahnit!” he called out, panicked and thirsty and lost. He wandered a few steps in pain, felt a pressure in his bladder and, crippled as he was, had difficulty even attending that necessity. It frightened him, in a shamed and inexpressible way, that even the privacy of his body was threatened. His knees were shaking under him. He made it back to the place where he had slept and sank down, hands tucked upward on his chest, eyes squeezed shut in misery.

There was sun for a while, and finally a whispering in the grass. He looked toward it, vaguely apprehensive, and an ahnit came striding down the hill, cloakless. By that, it was the one which had left him here: it came to him and knelt down, regarded him with wet black eyes and small, pursed mouth, midnight-skinned. It reached beneath its robes and brought out a ball of matted grasses, contained in some inner pocket; it spread it and revealed a loathsome mass of gray-green pulp. “For your hands,” it said.

He was apprehensive of it, but suffered it to take the cloak on which he sat and to shred strips from it ... finally let it take his right hand and with its three-fingered hand—two proper fingers and opposing member—begin to spread the pungent substance over it. The touch was like ice; it comforted, numbed. “Lie down,” it advised him. “Lie still. Take some of it in your mouth and you will feel less.”

It offered a bit to his tongue; he took it, mouth at once numbed. In a moment more it dizzied him, and he tried to settle back. It helped him. It took his numb hand then and bound it, and while it hurt, it was a distant hurt and promised ease. “The swelling will go,” it promised him. “Then I shall try to straighten the bones. And then too I will be very careful.”

He drew easier breaths, drifting between here and there. It tended the other hand and probed his whole body for injury. “Ribs,” he said, and with its cautious touches it exposed the bruises and salved them and bound them tightly, holding him in its arms when it had done, for the numbness had spread from his mouth to his fingertips and his toes. He breathed as well as he could, eyes shut, out of most of the pain that he had thought would never stop. Only his mouth was a misery, numb and dry; he tried to moisten his lips over and over and it seemed only worse.

It let him back then, and pillowed his head. “Rest,” it seemed to whisper. He was aware of the day’s warmth, of sweat trickling on him, of a lassitude too great to be borne. The sweat stopped finally, and the torment of his mouth grew worse.

“Water?” a far, alien voice asked him, rousing him enough to focus on its dark face and liquid eyes. “I can give it from my mouth to yours if you permit.”

The thought made his throat contract. He shut his eyes wearily and considered the incongruency of their mutual existence, finding their situation absurd and his fastidiousness merely a shred of the old Herrin Law, before he had begun to see invisibles and lost himself. The ahnit in his silence delicately bent to his lips, pressed his jaw open, and moisture hit the back of his throat with the faint taste of the numbing medicine. He choked and swallowed, and it let him go, letting his head back again. His stomach heaved, and the ahnit held him down with a hand on his shoulder. The spasm ceased and the pain which had shot through his ribs at the convulsion ebbed. The taste lingered. He moistened his lips and found some vague relief, suffered a flash of image, himself staring vacant-eyed at a too-bright sky because he was too drugged to care. The ahnit sat between him and the sun and shaded his face.

“It hurts less,” he said thickly.

And eventually, when thirst had dried his lips again: “My mouth is dry.” He did not want another such experience; but misery had its bearable limit. It leaned above him again, pressed its lips to his and this time brought up a gentle trickle that did not choke him. It drew back then, but from time to time gave him more, until he protested it was enough. It kept holding him all the same; and it spoke its own language, softly, nasals and hisses, in what seemed kindly tones. He rested, finally abandoned to its gentleness, too numb to rationalize it or puzzle it, only accepting what was going to be because of what had been.

Far later in the day the ahnit took up his hand and unwrapped it. “It will hurt now,” it said, and it was promising to, little prickles of feeling. The color—he focused enough to look at it—was green and livid and horrible, but the swelling was diminished. The ahnit probed it, and offered him more of the drug; he took it and settled back, trying to gather himself for the rest of it, resolved not to let the pain get through to him.

It did, and though he held out through the first tentative tug and the palpable grate of bone against bone, the subsequent splinting with knots to hold it, he moaned drunkenly on the next, and it grew worse. The ahnit ignored him, working steadily, paused when it had finished the one hand to mop the sweat from his face.

Then it started the other hand and he screamed shamelessly, sobbed and still failed to dissuade it from its work. He did not faint; it was not his good fortune. If it were my reality, he told himself in delirium, I would not have it hurt.It seemed to him grossly unfair that it did; and once: “Waden!”he cried out in his desperation, not knowing why he called that name, but that he was miserably, wretchedly alone. Not Keye. Waden. He sank then into a torpor in which the pain was less. He rested, occasionally disturbed by the ahnit, who held him, who from time to time gave fluid into his mouth, and kept him warm in what had begun to be night.

He was finally conscious enough to move his arm, to look at his right hand, which was swathed in fine bandage, fingers slightly curved in the splints. He was aware of the warmth of the ahnit which held his head in its robed lap, which—when he tilted his head back—rested asleep, its large eyes closed, lower lid meeting upper midway, which gave it a strange look from this nether, nightbound perspective,

The eyes opened, regarded him with wet blackness.

“I’m awake, “ Herrin said hoarsely, meaning from the drug.

“Does it hurt?”

“Not much.”

Its paired fingers brushed his face. “Then I shall leave you a while.”

He did not want it to go; he feared being left here, in the dark, but there was no reason he knew to stop it. It eased him to the ground and arranged the cloak about him, then rose and stalked away so wearily and unlike itself he could see the drain of its strength.

He lay and stared at the horizon, avoiding the sky, which made him dizzy when he looked into its starry depth; he looked toward that horizon because he judged that when the ahnit came back it would come from that direction, and he had no strength to do much else than lie where he was. All resolve had left him. Breathing itself, against the bound ribs, was a calculated effort, and the hands stopped hurting only when he found the precise angle at which he could rest them on his chest, fingers higher than his elbows. His world had gotten to that small size, only bearable on those terms.

XXIV

Waden Jenks: Does it occur to you, Herrin, that I’m using you?

Master Law: Yes.

Waden Jenks: If youwere master, you wouldn’t have to argue from silences. But you must.

He was on his feet when it returned, when the sun was just showing its first edge, when he had decided to climb the sunward slope to see what there was to see. Of what he expected to see—the river, the city—there was no view, just more hills; but a shadow moved, and that was the ahnit, which stopped when it seemed to have caught sight of him, and then came on, more wearily than before.

It said nothing to him; it simply stopped on the hillcrest where it met him and rummaged in the folds of its robes, offered something. He started to reach for it and the pain of moving his hand reminded him. “Food,” it said, and offered a piece to his lips. He took it, and found it to be dried and vegetable; he chewed on it while the ahnit started downslope and he followed very carefully, aching and exhausted.

It sat down when it had gotten to the nest it had made in the grass; it was breathing hard. When he sat down near it, it offered another piece of vegetable to him, and he took it, guiding it with bandaged fingers. “Better,” it said to him.

“Yes,” he said. The pain had been enough to fill his mind; and then the absence of it. Now he discovered that both states had their limit, that the mind which was Herrin Law was going to work again; he had had his chance for oblivion and chosen otherwise, and now—now oblivion was not so easy. The sun was coming, and day, and he was alive because of that same stubbornness which had robbed him of rest and sleep in Kierkegaard ... which, drugged, had wakened again, incorrigible. It saw ahnit, and existed here, robbed of its body’s wholeness; it just kept going, and that frightened him.

“More?” the ahnit asked, offering another piece to his lips. He used his hand entirely this time, though it hurt. “Why do you do this?” he asked the ahnit. There it was again, the curiosity which was his own worst enemy, wanting understanding which another, saner, would have fled. The ahnit, wiser, gave him no reason.

“What’s your name?” he asked it finally, for it was too real not to have one.

“Sbi.” It was, to his ears, hiss more than word.

“Sbi,” he echoed it. “Why, Sbi?”

“Because you see me.”

“Before,” he said. “Sbi, did you—meet me before? Was it you?”

“I’ve met you before. I’ve been everywhere ... in the University, in the Residency.”

He shivered, hands tucked to his chest.

“Why,” it asked, “are you blind to us?”

“I? I’m not. I see you very well. I’d be happier if I didn’t.”

“We exist,” Sbi said.

“I know,” he said. “I know that.” It left him nothing else to know.

“Do you want water?”

He thought about it; he did, but undrugged he was too fastidious.

“It disturbs you,” Sbi said.

“All right,” he said, and Sbi touched his chin to steady him, leaned forward and spat just a little fluid into his mouth. Herrin shuddered at it, and swallowed that and his nausea.

“I simply store it,” Sbi said, and hawked and swallowed.

“An appalling function.”

“Our nature,” said Sbi.

Herrin stared at Sbi bleakly. “Your reality. I’d not choose it.”

Sbi made a sound which might be anything. “Mad,” it said. “ Look, at the sunrise. Can you or I make it last?”

“Material reality. Mancounts where I’m concerned, and we can’t agree.”

“You’ve made things so complicated out of things so simple. There is the sun.”

In a single flowing movement Sbi rose and walked to the hillside, stood there with hands slightly outward and face turned to the sky ... sat down then, and ignored him entirely, seeming rapt in thoughts.

“Sbi,” Herrin said finally, and Sbi looked over a shoulder at him. “What do you intend?”

“When can you walk, Master Law? I’ve spent too much to carry you.”

“I can walk until I have to stop,” he said. “A while.”

“Don’t harm yourself.”

“What amI to you?”

“Something precious.”

“Why?”

Sbi stood up again. “Will you walk now?”

He considered the pain of it, and nerved himself, took the cloak in his hand and used his legs more than the ribs getting up. He used his splinted hands to put the cloak to his shoulders, and Sbi helped him. The act depressed him. He bowed his head and clumsily pulled the hood up, no different finally from other invisibles; safe—no one but Sbi would see him—even in the city no one would see him. He supposed that was where they might go.

But they walked slowly, and something of directional sense, the sun being at his back, argued that they were bound only into more hills.

I shall be further lost,he thought. He did not wholly mind, because while in one sense he was dead, he was still able to see and to feel, and the mind which sometimes frightened him with its persistence of life began to yield to its besetting fault, which was at once his talent and his curse.

“You don’t care,” he prodded at Sbi on short breaths, “to go back to the plain. Where are you leading?”

“Where I wish.”

He accepted that. It was an answer.

“See the hills,” said Sbi. “Smell the wind. I do. Do not you?”

“Yes,” he said. What the ahnit asked frightened him. “How much else?”

“Tell me when you know.”

It took the pose of Master. His face heated, and for a little time he thought, on the knife edge of his limited breaths and the weakness of his legs in matching strides with the ahnit. “I will tell you,” he said, “when I know.”

He walked, with the sun beating down on him, with the gold of the grasses and the sometime gold of flowers, and it occurred to him both that it was beautiful; and that humans did not come here—ever.

He looked to the horizon, where the hills went on and on, and it occurred to him that Freedom was full of places where humans had never been.

He thought of the port, where Kierkegaard played its dangerous games with Outsiders, and Waden sought to embrace the world; there were things Waden himself did not see, choosing his own reality, in Kierkegaard, and outward.

I could make it visible,he thought, and at once remembered: Icould have. Once.

He stopped on the next hillside, out of breath, stood there a moment. “I’m not through,” he said, when Sbi offered to help him sit down.

“Rest,” said Sbi. “Time is nothing.”

He started walking again, hurting and stubborn, and Sbi walked with him, until he was limping and his ribs were afire. “Stop,” Sbi said, this time with force, and he did so, got down, which jarred his ribs and brought tears to his eyes. He stretched out on his back, resting with his hands where they were comfortable, on his chest, and Sbi leaned over him and stroked his brow, a strange sensation and comfortingly gentle.

“Why are you blind to us?” it whispered to him.

It had asked before. “Do you play at Master?”

“Why are you blind to us?”

“Because—” he said finally, after thinking, and this time with all earnestness, “because if we shed our ways on each other ... what becomes of us and you, Sbi? How do we choose realities?”

“I don’t,” said Sbi softly.

He rolled his eyes despairingly skyward and shut them because of the sun. “You don’t care,” he said. “Your whole existence is of only minor concern to you.”

“There was a time humans saw their way to come here to Freedom; there was a time you were so wise you could do that; and there was a time you saw us, before my years. But you took your river and built your cities and stopped seeing us; you stopped seeing each other. Why are you blind to each other, Herrin Law?”

He shook his head slowly, not liking where that question led.

“Why did they cripple you?”

“Because I saw.” He lost his breath and tried to get it back, with a stinging in his eyes. He felt cold all the way to the marrow. “We’re wrong, aren’t we, Sbi?”

“What do you think, Master Law?”

“I don’t know,” he said, and blinked at the sun, which could not drive the cold away. “I don’t know. Where are we going, Sbi? Where are you taking me?”

“Where you’ll see more than you have.”

He shivered, nodded finally, accepting the threat. Sbi slid a thin arm under his shoulders and supported him as if the cold were in the air, resting with arms about him and sleeves giving him still more warmth.

And finally he found his breath easier again and knew he had strength for more traveling. “When you’re ready,” he said quietly to Sbi, “I am.”

Sbi’s three-fingered hand feathered his cheek. “Are you so anxious?”

“I won’t like it, will I?”

“I might carry you a distance.”

“No,” he said, and began to struggle, with Sbi’s careful help, to sit, and then to stand up. He was lightheaded. It took Sbi’s assistance to steady him.

Perhaps, he thought, there was much of Waden in Sbi, to persuade, to create belief—to prove, at the last, and cruelly, that he was twice taken in. Perhaps Sbi also had a Talent, and perhaps Sbi was coldblooded in his waiting, since he had learned to reason with a human Master. Waden Jenks had disturbed a long stability between man and ahnit; and he had had no small part in it.

Perhaps there was a place that Sbi would turn as Waden had.

He pursued it, to know. It was all the courage he had left.

And late, after hours of sometime walking and walking again, when the sun had gotten to the west and turned shades of gold, they crossed the final hill.

He had been ready to stop. His side hurt, and tears blurred. “I’ll carry you a little distance,” Sbi had offered, but he hated the thought of helplessness and kept walking, wondering deep in his muddled thoughts why of a sudden Sbi was so anxious to keep going.

Then he passed one hill and looked on the base of another mostly cut away; on a gold, pale figure which stood in a niche beneath the hill. There had been no prior hint that such existed, no prelude nor preface for it, in paths of worn places or adjacent structure. “Is that it?” Herrin asked. “Is that where we’re going?”

“Come,” said Sbi.

Herrin started downslope, and his knees threatened to give with him and throw him into a fall he could not afford; he hesitated, and Sbi took his arm and steadied him, descended with him, sideways steps down the slick, dusty grass until they were in the trough of the hills, until he could look close at hand at the figure sculpted there, in the recess of living stone.

It was ahnit. It was not one figure but an embrace of figures, a flowing line, a spiral ... he moved still closer and saw ahnit faces simplified to a line which be would never have guessed, ideal of line and curve in a harmony his human eye would never have discovered, for it did not, as he would have done, try to find human traits, but made them ... grandly other, grandly what they were. They shed tranquility, and tenderness, and, in that embrace, that spiral of figures, the taller extended a robed arm, part of the spiral, but beckoning the eye into that curve, in the flow of drapery and the touch of opposing hands. It was old; on one side the wind had blurred the details, but the feeling remained.

Herrin reached to touch it, remembered the bandages in the motion itself, and with regret, not feeling the stone, stroked it like a lover’s skin. He looked up at alien form, at something so beautiful, and not his, and loss swelled up in his throat and his eyes. “Oh, Sbi,” he said, “Did you have to show me this?”

There was silence; he looked back. Sbi had joined hands on breast and bowed, but straightened then and looked at him, head tilted. “You made such a thing too,” said Sbi. “For all the years the city was plain and people walked without meeting ... but you found something else.”

“I createdsomething else.”

“No,” said Sbi. “Don’t you know yet what you did? It was always there. It was always real. Your skill found it.”

It offended him. He was acutely conscious of the presence above him, the alien pedestal on which he rested his hand. “So where does it exist to be found?”

Sbi folded upright hands to brow, indicating something inward, a graceful gesture.

“Then I created it,” said Herrin. “It wasn’t there before.”

“No,” said Sbi. “You only shaped the stone. You made nothing that was not before. There is one maker; but an artist only finds.”

“A god, you mean. You’re talking about an external event. A prime cause. You believe in that.”

Sbi made a humming sound. “You believe in Herrin Law. Is that more reasonable?”

Herrin shook his head confusedly, suspecting the ahnit mocked him. And the work above him oppressed him with its power. He looked up at it, shook his head hopelessly. “Who made this?” he asked.

“Long ago,” said Sbi. “Long dead. The name is lost. Few come here now, so close to your kind; the place goes untended and the grass grows. If humans came here, they couldn’t see it; not minds, not eyes. But you see us.”

“We share a reality,” Herrin said. “That’s what you saw ... that this ... is in common. What I made, and this.”

“What you found in the stone,” said Sbi. “What you found in Waden Jenks.”

“I was mistaken about Waden Jenks,” he said bitterly.

“Perhaps not,” said Sbi.

Pain welled up in him the more strongly. He shook his head a second time and walked back from the statue, the entwined figures which beckoned his eyes into the heart of them. He made a helpless gesture, shook his head a third time, seeing things in the statue he had not seen before, the delicate work of the hands which touched, the faces which looked one almost into the other, suggesting a motion caught in intent, not completion.

“It’s triangular,” he said. “There should be a third. It’s missing.”

“No,” said Sbi. “It’s here.”

His skin contracted. “Myself. The one who sees.”

“Whoever sees,” Sbi said. “You stand in the heart of them. You’ve become their child.”

“Child.” He looked at the faces, the embracing gesture, and the contraction became a shiver. They were alien. And not. “It’s good,” he said. And in despair: “I might have attained to this. Sbi, I would have. But it’s better than mine. Old as it is ... whatever it is ... better. Before the wind got to it. ...”

“It was a strong thought,” said Sbi, “and it will take very long to fade away entirely.”

“You just leave it here to be destroyed. Alone. For no one to see.”

“Humans have this land now. Only a few of us remain to watch. You walk past such things and don’t see them; you don’t see them.”

“What do you see? Sbi, when you look at this, do you see things I don’t?”

“Perhaps,” said Sbi. “Perhaps not. We’re alone in our discoveries. It’s only such things as this that bind you and me together, by making us see what we thought we alone had found.”

He went back, aware of the trap set up for the eye, and was drawn in all the same, into gentleness like Sbi’s. He flexed at his hand and had no movement, reached out again to touch the stone, the shaping of a dead and three-fingered hand. He passed his fingers over the stone and felt very little of it but pain.

“Better than I,” he said.

“At seeing us. But looking on it has reached something in you. It finds, Herrin Law.”

He looked aside, his knees aching and unsteady, went back to the hillside and dropped down. He absorbed the pain dully, holding his breath, settled, holding his side with his arm, looking away from the statue which dominated the place. His eyes shed moisture, passionlessly; he hurt and he was tired and empty until he looked back at the statue which still beckoned.

Sbi had come; Sbi sat down by him. He thought of thirst and hunger when Sbi was there, needs which had begun to be obsessive with him, because he was unbearably empty, and the tremors had come back.

I shall die,he thought with a certain fatigued remoteness; and remoteness failed him. He wept, wiped his eyes with a bandaged hand, simply sat there, and Sbi edged close and patted his knee. He flinched. “I can’t take from you anymore,” he said. “Sbi, it ... upsets me. I can’t do it. And I’m not sure I can walk anymore. Are we done? Is this the place? If you leave me here I’m going to die.”

Sbi said nothing. In time Sbi got up and walked away and Herrin watched him go, saying nothing, only despairing. There was only the statue then, aged, anomalous in the sea of hills and grass, giving no indication it had ever borne relationship to anything understandable. It offered love. It was only stone. He had sent Sbi away and Sbi had simply gone. The sun sank and the wind grew cold, and he listened to it in the grass and watched the change of light on the stone.

And then, at dark, a stronger whispering, and Sbi was back.

Herrin sat still, the wind cold on the tears on his face, and still did not hope, because whatever Sbi intended, Sbi’s care of him was not sufficient to keep him alive, a simple mistake, a lack of comprehension.

Sbi came, squatted down, knees shoulder high as usual, held forth a small dead animal. “I have killed,” said Sbi in a voice quivering and faint. “Herrin Law, I have killed a thing. Can you eat this?”

He considered the small furry animal, and looked from that to the distress in Sbi’s eyes, sensing that the ahnit had done something on his behalf it would not, otherwise, have done. It looked, if ahnit could shed tears, as if it would. “Sbi, if we can get a fire, I’ll try.”

“I can make one,” Sbi said, and set the little body down, stroked it as if in apology.

“It’s not,” Herrin asked in apprehension, “something of value to you.”

“It was alive,” said Sbi, ripping up grasses and digging a bare spot. “I don’t wish to talk about it.”

Sbi worked, furiously, hands shaking in an agitation Herrin had never seen in the ahnit ... went off again for a prolonged time and came back again with sticks. Herrin watched in bewilderment as Sbi coaxed warmth, smoke, and then fire out of twirling wood, and then, comprehending, bestirred himself to push grass over for Sbi to add. Fire crackled in the night, a tiny tongue of brightness in the cleared circle.

“In this place,” Sbi mourned, and rose. “Eat. Please, when you are done, bury it, I don’t want to watch.”

Sbi fled. Herrin touched the small creature it had left, edged the limp, furry body close to the flames and suffered qualms himself, not knowing what to do with it but to push it into the fire and char it into edibility.

Oh, Sbi,he thought, trying not to inhale the stench or to think about what he was doing. Sbi had probably found a place remote from the smell and the memory. He swallowed the tautness in his throat and looked past the smoke to the statue under the moon, that mimed love. Sbi.