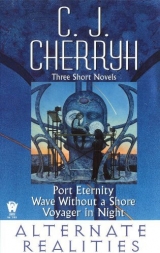

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

XIX

Waden Jenks: Inspire me, I defy you to do more.

Master Law: When I defy you to do more, I fear you can.

Waden Jenks: Then have you not, Herrin, met your master?

Master Law: Then have you not met the thing you say you fear most?

The finish came at night. The Work stood complete and it was all done—in the dark and with no admirers. The night was cold as nights in the season could be, with a beclouded moon and puddles of rain in the dome, water which had drifted through the perforations as a light mist that haloed the lamps.

Herrin had seen the finish near, so near, had pushed himself on after dark. “Light,” he had asked of Carl Gytha and Andrew Phelps who remained with him; and John Ree, who was there for reasons unexplained; and some of the others who had decided to work the off shift of other jobs they had gotten since the project finished, or after classes they had joined after the finish of the project and nighttime strollers who had found a place to be and something going on ended up lending a hand with the carrying of this and that. “Light,”he would say, his back turned to all of this activity, and peevishly, for his arms ached and he had bitten through his lip from the sheer strain of holding his position to polish this place and the other. It did not occur to him to inquire whether holding that light was a strain; or it did, but he was having trouble reaching a spot at the moment and forgot to ask afterward. His own pain was by far enough, and he was beset with anxiety that he could not last, that they would face the anticlimax of giving up, and coming back at dawn to do the last work, all because hisstrength might give out. He worked, and gave impatient orders that kept the beam on the sculpture so that he could see what he was doing; he ran sore hands over the surface which had become like glass, seeking any tiny imperfection.

“We’ll doit,” they said about him, and, “Quiet, don’t rattle that,” and, “The foundry hasit; we can get it. ...” The plaque, they meant: he had asked about that, in a lull for rest, and he trusted they were doing something in the matter, because he had shown them where it should go, had picked a paving-square which could come out, out where the square began to be the Square, and not Main. They had hammered the paving-square out during the day, and prepared the matrix, not only to set the names in bronze, but to seal the bronze to protect it from oxidation and from time. He heard some activity outside, and ignored it, locked in his own concentration on his own task.

He stopped finally and took the cup a worker thrust to his lips, took it in his own aching hands, drank and drew breath.

“Get the scaffolding down now,” he said, a mere hoarse whisper. “It’s done.”

“Yes, sir,” said Carl Gytha, and patted his shoulder. “Yes, sir.”

He swung his legs off the platform.

“It’s done,” someone said aloud, and the word passed and echoed in the acoustics of the dome ... done... done... done... drowned by applause, a solemn and sober applause, from a whole array of people who had no obligation to be there at all. He slid down into steadying hands, and there was a rush to get him a coat and to hand him his drink, as if he were their child and fragile. “What about the plaque?” he asked, remembering that.

“In, sir,” said John Ree. “Got it set and setting, and not a bubble.”

“Show me.”

They did, held their breath collectively through his inspection of it, which was exactly the size of one of the meter square paving blocks. It was set in and true as John Ree had said. They had lights on it to help dry the plastic.WADEN ASHLEN JENKS, the plaque said, FIRST CITIZEN OF FREEDOM, BY THE ART OF MASTER HERRIN ALTON LAW and ... Leona Kyle Pace, Carl Ellis Gytha, Andrew Lee Phelps, master apprentices ... Lara Catherin Anderssen, Myron Inders Andrews. ...

The names went on, and on, and filled the surface of the plaque, down to the foundry which had cast it.

Pace.That name was there, and how it had gotten there, whether they had used an old list and no one had wanted to seethe name to take it off before they had given it to the foundry, or no one wanted to take it off at all, or both of those things ... it was there, and an invisible was atop the whole list of workers and apprentices. He fingered the pin he wore, tempting the vision of those about him, and nodded slowly, and looked back past the encircling crowd of those who had gathered in the dark, where light still showed inside the dome and the scaffolding was coming down,

“Let’s get it all done,” he said, “so the sun comes up on it whole, and finished.”

They moved, and all of them worked, carrying out the pieces of the scaffolding, worked even with polishing cloths and on hands and knees, cleaning up any hint of debris or stain, polishing away any mark the scaffolding itself might have made.

The lights went out, and there was only the night sky for illumination, a sky which had begun to be clear and full of stars. Those who walked here now shed echoes, and began to be hushed and careful. The sculpted face of Waden Jenks, gazing slightly upward, took on an illusory quality in the starlight, like something waiting for birth, biding, and lacking sharp edges.

Some went home to bed, a trickle which ebbed away the bystanders, and more went home nursing sore hands and exhaustion, probably to lie awake all night with aches and pains; but some stayed, and simply watched.

Herrin was one, for a time. He looked at what he had created, and listened, and it still seemed part of him, a moment he did not want to end. Gytha and Phelps were still there. He offered his hand to them finally and walked away, out through the silent gates of the dome and into the presence of Others, who had come as they often did, harming nothing.

The silence then was profound. He looked back, and stood there a time, and enjoyed the sight, the white marble dome in the starlight, the promise of the morning.

Keye’s window ... was dark.

Not at home, perhaps.

He looked aside then, and walked on up Main, occasionally flexing a shoulder, recalling that he had missed supper. He resented the human need to eat, to sleep; there was a sense of time weighing on him. The mind, which he had vowed not to anesthetize again, was still wide awake and promised to remain so, working on everything about it, alive and alert and taking no heed of a body which trembled with exhaustion and ached with cramps. He thought of the port, with Waden’s guests; of Keye, with Waden; of Pace, whether shemight have come this night and gone away unnoticed; of Gytha and Phelps; of dinner and what it was he could force his stomach to bear; of Outside and ambitions and stations and the other continent and what he should do with that and how the morning was going to be and whether it would rain; and how he could keep going if he were to go to bed without supper, whether he could force himself to have the patience for breakfast, and how long he could keep going if he skipped both—and whether Waden Jenks, in perverse humor, would not try to make little of the day and the moment and all that he had accomplished. All this poured through his mind in an endlessly recycling rush, robbing him of any hope of sleep.

He was alone on the street; it was that kind of hour, and a chill night, and sane citizens were not given to walking by night without a purpose. He passed the arch in the hedge which led onto Port Street and remarked with tired relief that there were no Outsiders about and no prospect of meeting any.

“Tell the First Citizen I expect him at the Square tomorrow morning,” he told the night secretary. “Master Law,” said the secretary, “the First Citizen has it in his appointments.” That relieved his mind, and when he was about to walk away, “Master Law,” the secretary said to him, “is it finished?”

The interest, the question itself pleased him. “Yes,” he said, and walked away, suddenly possessed of an appetite.

He slept, on a moderately full stomach, in his own bed and without the wine.

And he wakened with the sense of a presence leaning over him, stared up startled into the face of Waden Jenks.

“Good morning, Artist. What a day to oversleep, eh?”

He blinked, gathering his wits, decided no one just wakened was capable of matching words with Waden, and rolled out of bed in silence, stalked off to the bath and showered and shaved while Waden waited.

“Hardly conversational,” Waden complained from the other room.

“What shall I say?” He negotiated the razor past his moving lips. “People who break into rooms shouldn’t expect coherent responses. What time is it?”

“Nine. I didn’t want to go without you.”

“Well, I wasn’t sure I’d go. After all, mypart’s done.”

“You’re incredible.”

“Meaning you don’t believe me?”

“Meaning I don’t.”

Herrin smiled at the mirror, ducked his bead, washed off and dried his face. He walked out where Waden was standing, searched the closet for clean clothes, nothing splendid, but rather his ordinary Student’s Black. Waden was resplendent in gray, expensive, elegant; but he usually was.

“You know,” Waden said, watching him, “that you could havebetter than that.”

“I don’t take care of things like that. I forget. I start to work and ruin clothes. I’m afraid I’ll never achieve elegance.” He pulled on trousers and pulled on his shirt and fastened the collar and the cuffs, sat down and put on socks and boots, all sober black.

“You really mean to wear that?”

“Of course I do.”

“Incredible.”

“I’m simply not ostentatious.” He finished, stood up, and combed his hair in the room mirror ... paused there, recalling the invisible brooch which was his private absurdity, his only ornament. He found Waden’s presence intimidating in that regard, and for a moment entertained the thought that thisday at least he should not play the joke.

No. On those terms he had to, or Waden did intimidate him.

He hunted out the clothes he had dropped the night before, unclipped the brooch and stood up, smiled at Waden, clipping it to his collar. “I’m ready to go if you are. Will Keye come?”

“She’s waiting outside.”

“ That’sremarkable. She’s always refused. Possibly a taste for the finished and not the inchoate.”

“Do you suggest so?”

“Ah, I was speaking of art.”

Waden smiled tautly. “Such deprecation isn’t like you. Areyou hesitant?”

“What, to offend you? Never. You thrive on it. But we’re both finished now, while before, you’d achieved and I’d done nothing. Somethingstands out there now.”

“Not to win Keye’s attention.”

Herrin laughed. “Hardly. Keye’s attentions are to herself and always have been.” He opened the door, stopped because there were Outsiders there. Blue-uniformed Outsiders.

“Something wrong?” Waden asked.

Half a heartbeat he hesitated, seeing the game and still finding it early in the morning for maneuvers like this. Invisibles. He wore a brooch. Waden Jenks had attendants. He stepped aside to let Waden out and closed the door. Keye was there, sitting in a chair a little distance down the hall, reading, legs crossed and nonchalant.

“Keye,” he said, and she looked up, folded the book and tucked it into her pocket, rising with every evidence of delight in the day.

“Good morning,” she said.

“Good morning.” He looked back at Waden. The escort was still with them. He smiled, oblivious to it all, and the three of them and their invisible companions trooped down the several turns of the stairs to the main level and out, into the pleasant sunlight.

“The light is an advantage, he said.

“I should think,” said Waden.

They walked across Port Street and the escort kept with them, dogging their steps. Notice them, Waden defied him; Herrin drew a deep breath and strode along briskly with Keye and Waden on either side of him, but in his heart he wasdisturbed, angered that Waden had found a way to anger him, a means which he had not anticipated to try to make this day less for him than it might be. Waden was Waden and there was no forgetting that. This troublesome fragment of his own reality existed to vex him—and that Waden took such pains to vex him—was in itself amusing.

Through the archway in the hedge and onto Main itself, the escort stayed; he heard them, a rustle and a crunching step on gravel and on paving. Looking down Main even from this far away he could see an unaccustomed gathering, where the dome filled the square at the heart of Kierkegaard.

His own people would be there, of course, and by the look of it, a good many citizens ... an amazing number of citizens. The street was virtually deserted until they reached the vicinity of the dome, and then some of the bystanders outside saw them, and the murmur went through the crowd like a breath of wind.

People moved for them, clearing them a path, and the main gateway of the dome emptied of people, as the crowd moved aside to let them pass; people flowed back again like air into a vacuum, with a little murmur of voices, but before them was quiet, such quiet that only the footfalls of those retreating echoed within the dome.

“Master Law,” some whispered, and “Waden Jenks,” said others; but Keye’s name they did not whisper, because the ethicist was not so public; the whispers died, and left the echoes of their own steps, which slowed ... even Herrin looked, as the others did.

Sun ... entered here; shafts transfixed the dark and flowed over curtain-walls and marble folds, touched high surfaces and faded in low, touched the clustered heads of the crowd which hovered about the edges, the first ring, the second....

And the third, where the central pillar formed itself out of the textured stone and dominated the eye. The face, sunlit, glowed, gazed into upward infinities; there was little of shadow on it. It seemed to have force in it, from inside the stone; it was hero and hope and a longing which drew at the throat and quickened the heart.

It was not Waden as he was; it was possibility. And for the first time Herrin himself saw it by daylight without the metal scaffolding which had shrouded it and let him see only a portion of it at a time. It lived, the best that Waden might be ... and for a moment, looking on it, Waden’s face took on that look, a beauty not ordinarily his; others, looking on it, had such a look—it was on Keye’s face, but quickly became a frown, defensive and rejecting.

Herrin smiled, and drew in the breath he had only half taken. Smiled when Waden looked at him.

And Waden’s face became Keye’s, doubting. “It’s remarkable, Artist.”

“Walk the interior, listento it, it has other dimensions, First Citizen.”

Waden hesitated, then walked, walked in full circuit of the pillar, and looked at the work of the walls, let himself be drawn off into the stone curtains of the other supports and of the ring-walls. Herrin stood, and cast occasional looks at Keye, who once stared back at him, frowning uncertainly, and at the invisible escort, who had also entered here. He knewthat they saw something remarkable, and for a moment had lost themselves in it. Waden walked temporarily unescorted; and if the escort was supposed to watch him, that failed too. Herrin looked beyond them, smiled in pleasure, because he saw members of his own crew, who grinned back at him.

Walking the circuit of the place, appreciating the folds and complications of it, took time. Herrin clasped his hands behind his back and waited, in the center and under everyone’s eyes, until at last Waden Jenks finished his tour and came back.

Waden nodded. “Fine, very fine, Artist. But I expected that of you.”

Herrin made a move of his hand toward the central pillar, the sculpted face, on which sun and time had now passed. Waden looked, for a moment surprised: the stone face had changed, acquired the smallest hint of a more somber look to come.

“It’s different, isn’t it?” Waden asked. The change was small and to the unfamiliar eye, deceptive. “It’s different.”

“It changes every moment that the sun touches it, with every season, every hour, with storm and morning and nightfall and every difference of the light ... it changes. Yes.”

Waden looked at it again, and at him, and reached and pressed his shoulder, standing beside him. “I chose you well. I chose you well, Artist.”

“A matter of dispute, who chose whom. I don’t grant you that point.”

“But how do I see it? How does anyone see it, in its entirety?”

Herrin smiled. “It’s for the city, First Citizen; for everyone who walks here and passes through it for years upon years, at varied hours in different seasons of his life, and for every person, different because of the schedule he keeps; different vision for anyone who cares to stand here for hours watching the changes progress. You’re a moving target, Waden Jenks, a subject that won’t hold still, and not the same to any two people. It’s time itself I’ve sculpted into it, and the sun and the planet cooperate. Done in one season it had to be. It’s unique, Waden Jenks.”

Waden had not ceased to look at the face, which grew steadily more sober, the illusion of light within it in the process of dying now. And the living face began to take on anxiety. “What does it become? What are the changes going toward?”

“Come at another hour and see.”

“I ask you, Artist. What does it become?”

“You’ve seen the Apollo; Dionysus is coming. It achieves that this afternoon.”

“This thing could become an obsession; I’d have to sit hour after hour to know this thing in all its shapes.”

“And, I suspect, season after season. Look at the time and the sun and the quality of the light, and wonder, First Citizen, what this face is. You don’t live only in the Residency any more: you’re here. In this form, in changing forms.”

“Would I likeall the faces?”

Herrin smiled guardedly. “No. In Dionysus ... are moments you might not like. I’ve sculpted possibilities, First Citizen, potential as well as truth. Come and see.”

Waden stared at him, and said nothing.

Whatever you see in it,” Herrin said, “will change.”

“I’m impressed with your talent,” Waden said. “I accept the gift, in both its faces.”

“No gift, First Citizen. You traded to get this, and you were right: it will give you duration. It’s going to live; and when later ages think of the beginnings of Freedom, there’ll be one image to dominate it. This. All it has to do is survive, and all you have to do is protect it.”

Waden sucked at his lips, as he had the habit of doing when pondering something. “Now time is my worry, is it?”

“It always was; it’s your deadliest enemy.”

The sober look stayed, and yielded to one of Waden’s quizzical smiles. “And your ally?”

“My medium,” Herrin said, and for a moment Waden’s smile utterly froze.

“We remain,” said Waden then, recovering the smile in all its brilliance, “complementary.”

There was Keye, frowning; and the invisibles, who stood with their hands tucked into their belts looking at the place and at the crowd, and the crew, who watched them. On the fringes of the crowd were the pair no one else might see, midnight-hued and tall and robed, skeletons at the feast—Herrin imagined wise and unhuman eyes, baffled—and Waden’s Outsiders watching them.

People did not make crowds in Kierkegaard; citizens were rational, cautious and conservative of their own Reality, avoided masses in which they could lose their own Selves. People gathered here, in this shell. And suddenly, when he looked at them in general and Waden did they began a polite applause, as people might, to express approval of something they had accepted as real and true—something they desired.

Strangers applauded, and the sound went up into the triple perforated dome, and echoed down again like rain. “Herrin ...” he heard amid it, “ Herrin,” “ Herrin Law,” as if his name had become their possession too. “Master Herrin Law.”

He smiled, sucked in the air as if sipping wine and nodded his head in appreciation of the offering. More, he spread his arms, seeing some of his chief apprentices near at hand, and invited them. “Carl Gytha,” he said, “Andrew Phelps. ...” He went on naming names, and the gathering applauded and faces grinned in pleasure. “Were you one of them?” people asked each other, and when one claimed to be, those standing next would all ask his name and touch him. Theirs were names written in bronze; names to last ... and it was the only art which had come out of the cloistered University into the streets of Kierkegaard.

“It’s unprecedented,” said Keye, gazing with analytical eye on the chaos.

“Of course it is,” said Herrin.

Waden laughed and squeezed his shoulder. “ Youare unprecedented, Artist; nowit’s unveiled, not before. That’s the nature of your art, isn’t it? It’s not stone you shape—time, yes, and Realities. You’re dangerous, Artist. I always knew you were.”

“Complementary powers, Waden Jenks.” He lifted his arm toward the face, which had lost its inner glow, which began to shadow with doubt, which led toward the other shadows of itself. “That... will be with generations to come. The weak will emulate it; the strong will be obsessed by it—because it challenges them. You’ll always be there. Give me substance, you asked, and there you stand.”

“I chose you well. Dispute what you will, I chose you well.” Waden grinned like a child, pulled him round and embraced him in public, to the applause of all the crowd; and the doorways were jammed with more people seeking to know what happened there. “Walk back with me, to the Residency. They’ll give you no rest here; walk back with us and let’s celebrate this thing.”

Herrin hesitated; he had planned to stay, or to do something else; to talk to Gytha and Phelps, he supposed, but the crowd overwhelmed him. He nodded, agreeing, and walked with Waden, with Keye, with the escort of invisibles who suddenly organized themselves to stay with them.

At the first wall of the dome, Waden stopped and looked back, with awed reluctance, but Keye watched him, and Herrin watched him and Keye.

Then they parted the crowd and headed back the way they had come, changed, Herrin thought, as everyone who came inside that place must be changed.

No one followed them—no one would dare—but the invisibles stayed at their heels, silent as they had been from the beginning.