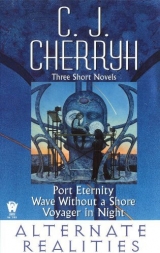

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

VIII

There was silence in the corridor, among Lindy’s pieces, the silence of waiting, when everything had been said, when the only needs were his own, and Rafe moved about those when he must, under the eyes of those whose remaining necessity was breathing, and that only because they could not forget to do it.

To eat, to drink—these things seemed cruel to do while they witnessed; to sleep—Rafe did sleep as he sat against the wall, a nodding of his head, a panicked look to see whether they were still there.

“All accounted for,” said Rafe Two, who read all his body language with more skill than Jillan ever could. “None of us have been anywhere.”—Meaning they were all intact, and as much themselves as they had been when he went to sleep.

“I’d think,” said Jillan, “it could have gotten its business together by now.”

“It’s waiting for something else,” Rafe said.

“What would it be waiting for?” asked Paul.

Rafe shrugged.

“You know something we don’t?” asked Rafe Two.

He shrugged again, wiped his face, got up and went about his toilet—shaved, because he needed it.

“Not sorry to miss that.” Rafe Two perched on the counter edge, transparent and only partly phasing with it. In the mirror, Jillan and Paul leaned against the console of Lindy’s dead panel, watching him with proprietary interest.

“I wish you wouldn’t stare,” he said.

“Sorry,” Jillan said. “It’s the only action going.”

Rafe-nothing crept along in the dark, blind as he had become. At times he thought he wept; but maybe that was illusion like the dark, for his hands felt nothing when he touched his face.

He had seen horror. Some of it still lived inside, and consciousness came and went; but he had seen his chance and slipped away, crawling in the dark.

He had had many limbs. And few. Now he had no understanding what shape was his. He only traveled as he could, as far as he could, and he supposed that limbs took him there.

Then something began to move beside him in the void, shadowy at first, with the outlines of some leggy, rippling beast. It brushed against him and the touch of it sent a shock through all his nerves.

He screamed. “Aii! Aiii!”it shrieked back at him, which so unnerved him he rolled aside from it and sat staring at this nest of coils and legs that swayed closer and closer, towering above him in black-glistening segments outlined in yellow light.

“Help,” it cried, “help, help—” It was not himself which understood this, but one of those ruptured areas of his mind, one of those places that hung in painful ruin, like threads that went into the dark, into inside-out perspectives.

He stared at it, and it oozed from its heap and surrounded him with its coils. He heard it sobbing, felt the shock of its nibbling up these stray threads, and the tears ran on his face.

“Come, come, come,” it wished him. He understood it through these threads. He recalled in horror what he was, and what pursued. “Get up and run,” the worm-thing wailed. “It will take you. Run!”

He wished to run. He tried to. A murkish glow came about them and the worm-thing fled.

“No,” said Paul’s chill voice above him, and a firm grasp gathered him up again.

He wept, having again more than several limbs, being in pain, while that monstrous shape enfolded all of them, in a welter of disturbed perspective. It swallowed up the threads, and he was blind.

“Paul,” he tried to say, “Paul, that isn’t right.”

“Rafael Murray,” the tall man said, taking him by the hand, bending down to their level. “Jillan—”—taking hers, so they knew something bad would come: nothing good ever came of Welfare strangers, not especially official ones in expensive suits, and he wished this man away with the horror of foreknowledge. “There’s been an accident,” the man would say next. “Out in the belt—”

That was what Paul did to him for revenge. It used his memories, put him back in that, time until he had no more recollection of any worm-thing.

“No,” the shining girl said, the star-jumper who had come to Fargone docks in her wealth and security. “No.” And he could see in her eyes the long-hauler’s prejudice against insystemers, that he would ever approach the likes of her and offer to sleepover with her, in this place longhaulers frequented and insystemers dared not come. She looked him up and down. She was all of, maybe, seventeen at most, unsure and offended in her inexperience. “Better get out of here,” she said.

And he: “My name’s Murray.”

“There a ship that name?”

“There was, “ he said, realizing it had been so small, so long ago, even spacers had forgotten. “Lindy was her name.”

Dead ship. He saw the pity. “Buy me a drink,” she said with fortitude. And maybe because she knew he had so little: “No, you have one on me.”

“No thanks,” he said. Desire had cooled in him. It was the first approach he had ever made to a woman of spacer-kind, after weeks of nerving himself. He guessed he might be her first, and even pitied her courage. She wanted her first with someone better. Someone memorable. She was good-hearted and would take him and never talk about it. Ever. The wound in both of them would live for years ... whatever he did now. “No. Give it to someone else,” he said. And he walked away.

was, at depth, dismayed at the near escape of Rafe-mind, <> detected it clear across the ship.

“Good for you,” <> sent the damaged Rafe-mind in a pulse transcending boundaries. “Good for you,”—in terms Rafe-mind might understand.

And a part of <>self, that portion which had several times participated in Rafe-mind—stirred.

“Good for me,” it said.

And foreseeing crisis, <> raised a simulacrum, and pushed it to the light.

The pain stopped. Rafe caught his breath, lying on the floor among Lindy’s ruins—seeing himself in duplicate beside Jillan and Paul—“O God,” he said, third of his kind, and gathering himself shakily to his feet, stood dazed in the shock of too many changes, far too fast.

“Damn you,” his brighter image shouted, and he thought he was intended, that the outrage was aimed at him.

“Damn you,” Rafe shouted at the walls, “—Kepta!”

“He’s real,” said Rafe Two. “Don’t frighten him worse than he is.”

Another duplication happened, another Jillan, another Paul, wide-eyed and terrified, who confronted their startled selves in voiceless shock.

“What are you up to?”Rafe screamed, himself, original, fists clenched. “Kepta– They’re not toys! They’re alive, you hear me, Kepta? They don’t just turn off. It’s not a bloody game! Stop—stop it, hear?”

There was riot among the passengers. “Stop!”<^> wailed. “Stop, stop, stop—”

<> did more than that. The pulse went through the ship in no uncertain strength.

Paul One flinched, dropped his tormenting of the Rafe-simulacrum and turned fierce attention toward the duplicates and the corridor <> protected.

“Diversions,” said . “Don’t regard them. <> means to lure you into reach.”

“I know,” Paul said, having gotten Iback wider than it had been. Iwas wide as all the universe. Iwas unstoppable, having tendrils in Rafe-shape, and in his own; and extensions into . He pulled at another memory, warped it out of shape, and Rafe-mind writhed in agony.

gained another section of the ship by complete default, for = = = = realigned = = = = self: the Cannibal had ambitions, and <>’s indirection and ’s aggressiveness advised = = = = which allegiance was, at the moment, the better choice.

<> sent out another pulse which resounded painfully through the ship.

But it did not deter desertions.

There was silence, dreadful silence, among Lindy’s ruin. Rafe recovered himself, wiped at his eyes, ashamed of the terror he had created. He was theirs, in common, their stability, the one thing impossible to counterfeit. He sensed their dependency. He sniffed, unheroically wiped his nose, sat down in the command chair and wiped his eyes again. None of them could touch him, none lay the least substance of a comforting finger on him, his sad-faced, devoted ghosts. They only waited in a half-ring about the console, two of everyone, even of himself.

I’m sorry,” he said to them. “Really sorry.” Another wipe at his eyes with the heel of his hand.

“That’s all right,” said one of his doppelgangers—he did not even know which one. They had a right to be ashamed, he thought; and upset; and they looked to be.

“Someone want to fill me in?” the other of his doppelgangers said. “I’m lost. I think several of us are. I think—” with a frightened glance at the one transparent as himself: “I was here; and talked to Rafe—about leaving the ship. Then it got me—in the dark. Am I far off? How lost am l?”

“Hours,” Rafe said, himself. “No farther.”

“You’re still hoarse.”

“Yes, he said, looking at the two Jillans. He could not tell them apart. There was no difference. That, more than anything, hurt him. He wanted there to be a difference. He wanted one to be real, an original, his sister; and there were two, both hurting, both claiming the right to existence and to him.

“We’re all right,” said the leftmost Paul, who had the rightmost’s steadying hand on his shoulder. The speaker’s voice was thin. “We understand. I think we’ve got the drill down pat. It’s just the shock. ...”

“Dammit,” said Rafe One. He stood up, holding out empty, helpless hands, to him, to the Jillan-newcomer. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry, hear.”

“I know,” said Rafe Three. “It’s what he says—the shock of it. Waking up—finding we’re not ... what we were prepared to be.”

“But we are,” said one of the Jillans. The other’s mouth was set hard; this one had Jillan’s most brittle look, don’t-touch-me, don’t-pity-me. “It’s what I said. We never know—we never know, after a copy’s made—which one we are.”

“Shut up,” the other Jillan said.

“You don’t need me,” said Jillan (he was sure now) One. The chin firmed, the head lifted. “I’m not your self.Stop thinking of me that way.”

“Sister,” Rafe said, to comfort Jillan. Both faces looked his way, instinctively, and the horror overwhelmed him.

“I didn’t plan—” Rafe Three said in his default. “I didn’t plan to be superfluous. Wasn’t that the word I just used of you? How many of us does it need, for God’s sake?” He walked off from them, through Lindy’s console. Rafe winced, knowing the self-torment behind that move. “It could get real crowded here,” Rafe Three said, recovering his humor, a desperate look back at all the surplus of them, a look upward as something went howling through the speakers overhead. “ Damnthat thing!” And then, with a futile reach at the com controls: “Com light’s on—Rafe, Rafe—for God’s sake, I can’t touch it—”

Rafe moved, dived through the simulacrum, pushed the button; but the light went out under his hands and the sound was gone.

“Games,” he said. “Dammit, it’s playing games with us!”

“((()))!” <> shouted at the culprit, but ((())) ran, evaded a wandering segment of = = = = and kept screaming.

“Lonely,” ((())) said when ((())) had stopped eventually. This was improvement of a kind. ((())) had acquired an opinion after eons of raving lunacy. ((())) peered from behind a weak barrier ((())) had erected and looked doubtfully at <>.

“Away!” <> raged at ((())). “Get out of here!”

((())) drew ((()))self up on all ((()))’s legs and dropped the barrier. “((())) remember,” ((())) said, “flesh—”

And that word whispered through the ship with a multitude of connotations as ((())) fled.

<^> leapt out of ((()))’s path and shuddered, coming close to <>.

“Why haven’t <^> deserted too?” <> wondered.

“Bravery,” said <^>.

“I was the last it copied,” Paul said, in the silence, in the devastation of them all. “I think—I think I know things. I think my double understands best what’s going on. I was the last it took.” He walked over to the counter, settled on the edge in a parody of sitting, for it was hard to recall after a lifetime of having a body that it made little difference where it rested, except it put him near the one of them that could occupy a seat and make its fabric give. Rafe looked at him—bruised, shadow-eyed. Rafe Two stood godlike in his handsomeness; Three had a foredoomed look, brooding and quiet. And Jillan, his Jillan, was the image of her brothers, her face so much like theirs and so much more delicate, so doubly resolute, in both her shapes. His own doppelganger came to settle at his side– so tired he looks,Paul thought, shocked at himself. He drew an unneeded breath, straightened his shoulders, looked once and achingly at Jillan.

“Kepta and I,” he said, “had a real frank talk. I don’t know all it expects of me. I suspected it might lie, in several ways. Eventually I—had another impression. That Kepta’s got a problem and he’s scared. I don’t know what he’s up to now.”

“Do you know more than I do?” his doppelganger asked him.

“No,” he said. “More than that, no. God help us.”

“God help us,” it echoed. “Both.”

“What’s it want?” one of the Rafe-doubles asked. Three, Paul thought. “I wish someone could bring me up to date.”

“There’s one of me,” Paul said quietly, “my first version, Kepta said. Said he’s got some kind of enemy—Kepta has. And that other version of me is on that enemy’s side and crazy as they come. Maybe I know how. But that’s all I know—” he said to Rafe, slid a glance at Rafe Three. That Rafe was afraid—he saw it, and felt a dim, ugly affirmation of himself.

My darker side,he thought, because it gave him, deeply, secretly—satisfaction. Rival.He seized on that idea, refused to let it go until he had turned all sides of it to the light. Because I’m not strong, and he is. And Jillan is.He lifted his head and looked at the Original.

“Barriers,” he said. “Barriers, Rafe. Jillan—I love you two, you and Rafe. That’s the one thing I have to keep telling myself over and over. Kepta said I have to figure out why I love you. And now that I do try to figure it out it’s very simple. I’m not a good man without that.”

“That’s nonsense,” Jillan said.

“Oh, but it’s not. Without someone to trust I’m not trustable myself. I work on reciprocities. You provide me—environment. You’re my morality. And if you fail me I’m worse than lost. You get my other side. Or it gets me. There’s a part of me wants more than anything to be like you, independent. Capable. There’s a part of me wants to prove you’re not capable at all; wants to see you’re like me, in need of props and braces. Wants to—affirm my own humanity, I guess, by proving you’re like me—Don’t say anything,” he said to Jillan, because she began to protest the mandatory, affirming things. “You’ve never seen my insides. I think you needed me, all right. Needed my station credit, someone to work with you, another strong back; my—friendship. I believe that. I really do. You and Rafe. I don’t think you really have the least idea what I wanted when I dragged a merchanter into marrying. It was that kind of thing. Affirmation. Environment. Something to define meand give me the props I need.”

“You’re not like that,” Jillan said. HisJillan, the older one. “That isn’t why I married you.”

He looked at her, smiled sadly at loyalty reflected in both her versions. “But I am,” he said. “That’s what you got, Jillan-love. A bad man who’s told you the truth for once, because he had to tell it to himself.” He gathered himself to his feet and walked off from them, their eyes. Looked back again, having remembered suffering beside Jillan’s and his own. “Kepta said a lot would rest on me; and knowing me,” he said to Rafe Three, “Kepta judged I needed help. Maybe that’s why you’re here. I don’t know. You’re stronger than I am. I need you.” And having admitted that: “I’m full of shadow-spots. He said you had only one secret. I won’t ask you what that is.”

“I have a thousand,” said Rafe Three in uncomfortable charity. “Doesn’t any human born?”

“You have one,” Paul said.

“Damn that thing!” Jillan cried, leaping to her feet. “It’s got no bloody right to mess with us!”

“And you,” Paul said, staring at her directly, “ useyours.”

Her eyes fixed on him in sudden, white-edged shock. “He told you? He told you that?”

“Not what it was. Just how you work.”

“What does it know about humanity?”

He listened to that. Secrets wielded like a shield, deflecting questions that could go through to the heart. He nodded, quite calm about it, armored in the truth. “Trust isn’t the way you work. You never trusted me with the truth. Maybe I couldn’t have stood it. You always protected me.”

“What’s that supposed to mean? You’re not making sense, Paul.”

“You are. Making sense, I mean. To me. Don’t change. I love you. Love me back. That’s all I want. Does it cost too much?”

“No,” she said, not understanding him. She would not, he thought, understand him; or believe truth when she heard it, though she was wise in other ways. And in the wickedness of his heart he found that he was in one way stronger, and wiser, and for once he had something to give away.

He smiled at her. Watched both her versions frown.

“Rafe,” he said, looking back at the Original. “I figure when the stuff starts to go, hard, you know?—we’ll be separate. Could be any minute. Maybe when we figure something essential Kepta wants he’ll snatch us out of here. I want you to know—you’re brother, father, mother to me. She,my real family—they made her mother in a lab; she and gran did the best they could with me. Ma wasn’t any rebel like I told you. They shot her by accident. She just got in the way. That was the way she was. Like gran. Wrong place. Wrong time. That’s all.”

“Guessed she wasn’t any rebel,” Rafe said in the faintest, most diffident of voices. “They gave you that station share. They never would have, if she’d been on the rebel side. However young you were.”

He nodded, head up, discovering the nakedness he had always suspected with them. “Couldn’t impress you, could l?”

“Didn’t have to,” Rafe said. “Not that way. You’re family, Paul.”

“Family,” he said back. “Yes, you are. All the love and hate and everything that is. Everything that holds me together. I want you to know that.”

He felt a hand slide past the hollow of his arm, his own Jillan’s slim, smooth touch; her head pressed against him.

And beside the counter, the other two, the new-made set, not touching, nonparticipant and already alive, because they had chosen not to touch, because they had not consented to what he felt. He put his arm about his Jillan. At last his doppelganger did, for whatever his own thoughts were—put his about the other Jillan, who drew a deep, insubstantial breath for hers.

“It said,” said that other Jillan, “that twoof you went wrong.

“One of me,” said Rafe.

“Or me,” said Rafe Two, moving finally, to sit on the counter edge. “We don’t really know which one.”

“Does it make a difference?” Rafe one asked

“As to how far off it is,” said Rafe Two, “as to how it adapts to the dark—it might.”

The Original shook his head. “No. If it came from as early as I think it might—no difference, except in what it’s been through.”

“Isn’t that always the difference?” Paul asked, discovering this in himself. “Events change us. Isn’t that why we all exist? I’m not that other Paul. He’s not me. We’re all of us—very real.”

“I feel that way,” Rafe Three said with a small, desperate laugh. “I feelalive.” And looking distractedly at Jillan: “You said that once.”

So <> had made <>’s move. was not impressed.

“Mistake,” said, and unleashed the entity had made, Paul-Rafe, while stalked larger quarry.

“See,” <^> wailed, knowing this, skipping along at <>’s side as they proceeded elsewhere in the ship. “<> have lost.”

“Not yet,” <> said.

<^> remained. Puzzled; and angry. And frightened, that foremost, as <> and <^> built barriers.

“This is retreat,” <^> said.

“Maneuver,” said <>.

“It’s late for that,” said <^>.

“Everything is late,” <> said.

“<>,” <> heard, a pulse that made <> wince. had gathered strength. “<> , am waiting for <> to cross the line.”

Meanwhile, Paul One had moved, slipping through the corridors. = = = = went at Paul One’s side, in all = = = =’s segments. Some of them shrieked in protest, but they all went, having no choice in this new alignment.

There was dark in the side-corridors of Fargone docks, the kind of deep twilight of betweentimes, between main and alterday, and someone stalked. Rafe ran, in starkest terror.

“Hey, miner-brat,” security yelled and he ought to have turned and faced the man, but he had no pass to be across the lines at this hour, a miner in spacer territory.

He rounded a corner, slid in among shipping canisters awaiting the mover to pick them up. Their shadows passed and his heart crashed against his ribs in regular, aching pulses.

They searched. If they caught him they hauled him in for questions; questions led to Welfare, and Welfare to assigned jobs. Forever.

“Please,” they would ask of spacers, shyly on the docks, asked them daily, nightly, in the shadows of twilight hours, “sir, got a fetch-carry? Just a chit or two?”

Most had no job for them. Some trusted Jillan but not him. Docksiders stole. Now and again one gave him a message to run—payment at the other end. Sometimes he was cheated. Once a white-haired woman offered him money and a bed and he took the key she offered and went to that sleepover, humiliated when he discovered what she had not wanted at all. Just charity, for a starving kid trying to stay off Station Welfare lists.

He was humiliated more that he had been willing to sell himself, for what she gave away.

And he did not tell Jillan about that night. He did not tell it even to Paul.

“The time has come,” <> said, and made two simulacra. “Wear this,” <> said to <^> of Jillan-shape. “<^>’ll find things in common with her.”

“I don’t know what to do,” Paul said to Rafe’s question. “I don’t—”

And there were two more of them: a fourth Rafe; a third Jillan standing there, in front of the EVA-pod that reflected them and the hall askew in its warped faceplate.

A pair of them, with that deep-eyed stare. There was horror in newcomer-Jillan’s eyes.

“Kepta,” Paul said, guessing.

And: “Kepta,” said Rafe, getting to his feet as the rest of them had, “dammit, let Jillan be!”

“Call him Marandu,” Kepta said of the anxious Jillan-shape beside him. “That was something like his name. Hedoesn’t quite describe him. But shedoesn’t do it either.”

“More games.”

“No,” Kepta said. “Not now.” Jillan/Marandu had hold of Rafe/Kepta’s arm. Kepta shook off the grip and walked aside with a glance upward and about as if his sight went beyond the walls. “It’s quiet out there now. It won’t be for long. It’s moving slowly, expecting traps.”

“What are you here for?” asked Jillan One.

“You,” Kepta said, and turned a glance at Paul; “It’s time.”

“Leave Jillan here,” Paul said.

“Which one?” it asked him, and sent a chill through his blood. It faced him fully. “You choose. A set of you will stay here safe. A set of you will face it. Likely the encounter will ruin that set. Which?”

“ Noneof them,” Rafe said. “Leave them alone.”

“ Itwon’t,” Kepta said, and looked back at Paul. “I sent a full set here—to keep the promise; I brought them early so that they would have some contact with the oldest. Continuity. That’s as much as I could give. Now it’s time, and no time left. Four to stay and three to go. Shall I choose? Have you not discovered difference?”

“I’ll go,” Paul said. He cast a look at his doppelganger, poor bewildered self, standing there with its mouth open to say something. “No,” it protested. “ No.It’s why I was born, isn’t it?”

Then things seemed clear to him, clear as nothing but Jillan had ever been. “Take Jillan and Rafe of the new set,” he said, “and me, of the old.” He looked straight at his doppelganger as he said it, proud of himself for once. “I know what the score is.”

And the dark closed about him.

“No!”he heard Rafe’s hoarse shout pursuing them. He felt a hand seek his in the dark—Jillan’s. Felt her press it hard. He trusted it was the latest one, as he had asked. “You did the right thing,” Rafe Three said—unmistakably Rafe, clear-eyed and sensible, as if he had drawn his first free breath out of the bewilderment the others posed. “What now?”—for Rafe was not senior of this group.

They were gone, just gone, and there was silence after. Rafe stood helpless between Rafe Two and Jillan; and Paul’s hours-younger self, his substitute, whose look at Jillan was apology and shame.

She just stared at that newborn Paul, with that dead cold face that was always Jillan’s answer to painful truths.

“What’s happening out there?” Rafe Two asked. “What’s happening?”

“War,” said that Paul, in a faint, thin voice. “Something like. That Paul that changed—it wants the rest of us. And he’s got to stop it. Paul has to. The real one. The one I belong to. The one I am.”

“It can make more of us,” Jillan said. “It can keep this thing going—indefinitely.”

“It won’t,” Paul Three said, “It won’t take the chance. It said it wouldn’t risk the ship. Kepta’s words.”

“It—” Jillan said; and: “O God!”—her eyes directed toward the tunnel-length.

Rafe spun and looked, finding nothing but dark; and then the howling sound raced through the speakers, leaving them shivering in its wake.

made haste now, sending tendrils of self into essential controls. encountered elements of <>, which had expected, but <>’s holdouts were growing few. There had been major failures. <>’s resistance collapsed in some areas, continued irrationally in others.

Other passengers, such as |:|, declared neutrality and retreated to the peripheries.

Paul, meanwhile.... wielded Paul/Rafe like an extension of self.

The variant minds of the simulacra were the gateway, reckoned. <> had invested very much of <>self in the intruders, which had proved, in their own way, dangerous.

The passengers were mobilized, as they had not been in eons. There was vast discontent.

“<> has lost <>’s grip,” whispered through the passages, everywhere. “<> has been disorganized. am taking over. Step aside. Neutrality is all ask—until matters are rectified.”

“Home,”said one of [], with the ferocity of desire. [] forgot that []’s war was very long ago, or that []’s species no longer existed, and whose fault that was. But they were all, in some ways, mad.

Kepta joined them, a Rafe-shape with infinity in its eyes. It stood before them in the featureless dark, and Paul faced it in a kind of numbness which said the worst was still coming; and soon.

He was, for himself, he thought, remarkably unafraid; not brave—just self-deprived of alternatives.

“It will be there,” Kepta said, turning and pointing to the dark that was like all other dark about them. “Distance here is a function of many things. It can arrive here very quickly when it wants.”

“What’s it waiting for?”

“My extinction,” Kepta said, “and that’s become possible. You must meet it on its own terms. You must stand together, by whatever means you can. You will know what to do when you see it, or if you don’t, you were bound to fail from the beginning, and I will destroy you then. It will be a kindness. Trust me for that.”

And it was gone, leaving them alone; but a star shone in the dark, a murkish fitful thing. Rafe pointed to it; Paul had seen it already.

“Is that it?” Rafe wondered.

“I suppose,” said Paul, “that there’s nothing else for it to be.”

“Make it come to us,” Jillan said. “Get it away from whatever allies it has.”

“And what if its allies come with it?” Paul asked. “No. Come on. Time—may not be on our side.”

They advanced then. And it moved along their horizon, a baleful yellow light.