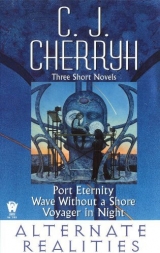

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

“How long were you awake?” Paul asked. “I died.” His voice went faint; the muscles of his insubstantial face shook and jerked with such semblance of life it jarred. “I am dead.Isn’t that what you’ve been insisting? I remember what it did. I remember the pain, Rafe. And it wasn’t any damn humanitarian concern.”

Rafe sat and stared at him, looked away finally, for Paul had begun to cry and to wipe his eyes, and finally faded out on them.

Jillan went after that, just winked out.

“How do you do that?” Rafe asked his double, hollow to the heart. “Where do you go when you go out? That dark place?”

“Don’t get superstitious about it. It’s just a place, that’s all. You think hard about it—I think we’ve got a simple off-on with a transmitter somewhere.”

“It wouldn’t be simple.”

“Bad choice of words.”

“Dammit, I don’t like arguing with you. It gives me the shakes.”

“You ever wonder how I found you,” Rafe Two asked, waving a hand toward the vastness of the hall, “in all this? Coincidence?”

“Something’s pushing the buttons.”

“Don’t put it that way,” Rafe Two said and hunched his bare shoulders, hands tucked between his knees. “You make me nervous, twin.”

“You scared of dying?”

Rafe Two nodded, slowly, simply. “So are they, I think. Jillan and Paul. They’ve got experience.”

“I’m hungry. My knees ache. Do yours?”

“No body left—brother. Got nothing like that left to bother me.” The eyes were his own, and worried. “I’m going to go after them.”

“Don’t leave me here!”

Rafe Two looked at him. “It’ll see we get back together. Won’t it?”

“I have to go back to the ship. I have to. We’re gaining nothing out here wandering these passages. Get them back. Come back yourself. To the ship. When you can.”

“The ship.” The doppelganger gave a dry and bitter laugh. “It won’t let you lose that either, will it?”

“I’m afraid for them.”

“So am I.”

The doppelganger left, a winking-out more abrupt than Paul’s.

So there had been violent parting of the ways; one fled: two gave chase; the living one pursued a painful trek back, <> surmised, to origins.

is gathering malcontents,” said = (+) =, on leave from its cannibalistic whole.

<> was amused, with that part of <>’s attention it had to spare. Trishanamarandu-keptarode inertia at the moment. <> had figured (accurately thus far) that this carbon-life, having ships capable of FTL, having the tendency to cluster together as they seemed to do, would not disperse themselves in long solitary voyages in between the stars and points of mass, so this vacancy seemed a likely place to coast undisturbed. <> preferred a few problems at a time: there were the passengers, after all, who were disturbed enough at three outsiders in their midst. So <> did not court attack from this carbon-life at large. The species might, <> judged, with the example of Jillan-mind, be very quick to attack if it had the chance.

<> was learning things. Jillan-mind and Rafe-mind in particular were responsive to the logic <> discovered in the primitive machinery, while Paul-mind refused focus, being a flood of strong responses on every level. They were not structurally the same, but there were strong similarities. Conclusions suggested themselves, but <> did not rush headlong into judgment, having wide experience which made surmise both slow and elaborate.

Throughout the ship other passengers were waking, more and more of them during this interlude, some of which had not waked in a very long time. Often they blundered into the barriers <> had made. But nothing got into the area where the visitors were at liberty.

This defense <> managed with one part of <>’s mind, and used another small probe on the Jillan-consciousness.

<> erased one temporary image, which began to disintegrate in subtle ways; but it was no effort now to enter the Jillan-mind on the level <> had already achieved, and <> integrated another.

Trishanamarandu-keptahad found a large bit of debris, meanwhile, and stored it for conversion, as it dealt with dust and interstellar hydrogen. <> constantly attended such things.

<> called up the Rafe-mind, and probed him with some sophistication, seeking out the differences, both physical and otherwise.

Rafe was, <> decided, less resilient but more stubborn. His barriers lasted longer, and snapped with a suddenness and disintegration that made <> suspect for a moment <> had met some clever trap, so disorienting and painful the reaction.

It was shock, <> decided. Rafe-mind had simply no experience with losing on that level, and he had met defeat without expectation, absolute and devastating, when he had planned to endure pain and outwait it.

From this collapse, Rafe-mind did not reintegrate, though <> observed him patiently and gave him every chance. So he would perish, ultimately. <> destroyed him and recreated him afresh.

It was paradoxical defense at best. It hinted irrationalities, capacities that would be augmented by physical systems in the living one, and Rafe himself had been, <> thought, stunned by his own failure.

<> suspected then why this one had survived in physical form, and why <> had so quickly broken him.

<> had robbed him of motives, that was what. That was why Rafe-mind had come apart, in solitude, without the other two.

<> did not intend Rafe-mind to learn this about himself; not yet.

Distress continued among the three newcomers. The simulacra which had gotten loose ran at hazard through their confinement, emitting terror as they went.

Paul, <> thought; it would of course be Paul in the lead, and <> was right in <>’s assessment, <> discovered, reaching out to prevent him from a meeting with = = = =, which lurked in anticipation.

= = = = was outraged. But <> pent Paul Gaines safely out of harm’s way, diverted Jillan elsewhere, and established barriers in haste, having <>’s mind on a dozen other matters.

“Robber!” = = = = hissed.

“Out,” said <>. And = = = = went, calling in = = = =’s segments that were still at large. Most howled in protest. But they came. And the idle curious scattered.

Trishanamarandu-keptafound a second bit of rock, and sucked that down as well, while automata attended small repairs.

<> considered Lindywith another part of <>’s large mind, its structures, its simplicity, for <> had not yet sent the mote to feed Trishanamarandu-kepta’s needs. It might. But <> thus far refrained, finding interest in it.

Then because Paul continued to batter himself unreasoningly at the barriers, <> gave Paul a Rafe-simulacrum to keep him calm and let him wonder why that Rafe should be difficult to wake. Paul shook at him and wept and cursed. That, <> judged, would keep him out of mischief.

For more immediate purposes <> chose the Jillan-face.

V

Rafe went striding through the dark, calling Jillan and Paul by name, tireless in his pace and wishing desperately that endurance made some difference—for they would not grow tired here any more than he would, and he could not overtake them by all the laws he knew of this place. He could never overtake them until one of them came to his senses and stopped.

Paul was running; that was what Rafe guessed, running in hurt and fear. Paul had always been the gentle one, the little boy who had played at explorer and shuddered at the dark—

—Space frightens me,Paul had confessed to him once. I’m all right in ships; just keep walls around me. When I have to go EVA, I just keep looking at the ship, the rock, whatever. Give me boundaries.

Paul was station-born. He had a stationer’s way of looking at things, and large concepts got to him, like the idea of staring time in the face when he looked out at the stars. The inside-out of jump frightened him. There were dimensions of time and space Paul staunchly refused to believe in, or at least to think of, even while he used and traveled through them.

I’m not dead,Paul had insisted; Paul Gaines could not die; no stationer could be so much alone as that. The universe would not permit so gross a violence to the devoutly nonviolent.

“Paul,” Rafe called, aching for him. His own ill-timed joking, his bloody sense of humor, the other Rafe’s—Paul did not support the contradictions. “Paul! Jillan, come back!”

Eventually a light came toward him, looking like a star at first, then a figure walking with that gliding, too-rapid stride that was the law within this place.

It was Jillan, by herself.

“Where’s Paul?” he shouted at her, but Jillan kept coming without answering, and that silence chilled him, intimating that something dire had happened—Jillan, without Paul.

Her face was dreadful when they met, her eyes vast and shadowed, and again the illogicity of themselves overwhelmed him, that whatever they were could suffer– Have we flesh of a kind,he wondered, bodies somewhere, beyond this dark? Metal bodies standing in a row or going through pointless motions? O Paul, Jillan—

“Where’s Paul?” he asked his sister.

“R-r-r-aaa-ffe,”the lips shaped, a hoarse, rasping effort with Jillan’s voice. It reached for him.

“O God. God, no!” He flung himself back and ran with all his might.

He hit a barrier, not a hard one, but a slowing of his force until he could not move more than a few feet in any direction. He felt a touch on his shoulders. He turned and met Jillan’s eyes, encountered its embrace.

It was strong, stronger than he was by far. “Let me go,” he cried, and struck at this thing, beyond any fear of harming Jillan. “Let her go, damn you!”

It hugged him to its heart. “R-r-raaa-ffffe,”it said, handling him with irresistible force, as if he had been a child in Jillan’s arms.

He screamed, yelled out names—his own was one– “Rafe!”as if his other self could hear him, help him, at least know that he was lost.

Jillan carried him some distance and stopped at last, just stopped, and let him go. Free,he thought, having wild hope of escape. He flung himself away as she winked out, but he came up against a barrier, solid as a wall.

Pain hit, and he screamed and went on screaming, from shock at first, and then because he could not stop.

“Rafe,” he heard Jillan say out of a vast void darkness; and he waked again, blind and numb at first, lying on nothing, face up? face down?

Then Jillan was by him, kneeling there bright with gold-green glow, with seeming tears glistening in her eyes and spilling down her face. He felt her hands as she shook at him. “Come on, Rafe, wake up, you’ve got to wake up, hear me?”

He moved: he could, and writhed out of her reach, sat there shivering and staring back at her.

“Paul’s lost,” she said in a hoarse and hollow voice.

He shivered then, not for Paul, whose fate seemed a thousand years ago to him; but for himself, for the inexplicable that happened to him and went on happening in this blind dark.

“We’ve got to get back,” he said at last, for it was truly Jillan. He convinced himself it was. He forced sense past numb lips, going on living, desperately ignoring memory as something unmanageable. “We’ve got to get back to the ship, tell him—” as if his living half would know what to do, would have some holistic view he lacked. He no longer trusted himself or anything he saw. He had dreamed his kidnapping. He had dreamed the pain. He wanted to believe in none of it. “Jillan—how did you find me?”

“I just kept walking back,” she said. “Paul’s lost.He’s out there somewhere and he’s not answering or something’s happened to him—”

Something happened to me,he started to tell her, facing her hysteria; and some reticence held the truth dammed up. It was Jillan. He kept looking for flaws and cracks, but it was indeed his sister. He had to believe it was. “Let’s get out of here,” he said, not wanting to be touched by her, not wanting to look in her eyes. Have you met something too?he wanted to ask. Have you already met it?

Is it somewhere still inside you?

Is it alive in me?

“I’ve tried to get out,” she said.

“What do you mean, tried to get out?”

She nodded toward the dark in general, or in a particular direction. “A few paces off—there’s just a wall.” She hugged her knees against her, tight, muscles rigid in her arms. “It’s got us penned here. That’s what.”

He stood up and tried, all round, but it was like hitting some painless wall of force, insubstantial and absolute at once. He battered it with his fist, and his arm simply stopped short, impotent and forceless.

“Aaaaaaiiiiiieeeeeee!”something wailed, just the other side.

“God!” he said, and staggered back, crouched down in primate tuck, shoulders hunched, facing the barrier with Jillan at his back. He felt vulnerable so, deliberately kept staring into the dark, determined to believe in her, that it wasJillan behind him.

Sister,he thought, sister.They had called him the Old Man, she had. Paul had. The thinker, captain, planner, head-of-family, for all he was only twenty-two. He had outright failed them, all down the line; and he saw it now, how they had looked to him, Paul in his way, Jillan in hers, because he told her he could do it all for her and Paul, and she trusted that he could. She handed her life and future to him– Here, brother, I’ve got what I need; I’ve got Paul: you take us, and do something, make something of yourself and us–

–merchanter-man, who was nothing without his ship, his sister to give it children—

He was not sure of Jillan now. He was not sure of Paul. If Jillan was truly gone nothing mattered, not even Paul.

But he would, he discovered, go on fighting, as long as it was not Jillan herself who struck the blow. Being a merchanter brat, he had a certain stubbornness: that was all he could call it at this point, a certain rock-hardness at the center that did not know where to quit.

Not revenge. That was nothing. It was Murray-stubbornness, that lasted through the War, the mines, Lindy’s making, the Belt. He had always wondered if there was anything in him but Jillan.

Now he knew.

And he was, he thought with a jolt that ached, only the merest shadow of the man. The real substance of him was back in the lighted corridor, waiting for him, depending on him.

Two of us,he thought, and it occurred to him that, being Old Man, he still had one living crewman to protect. He was father to one at least. Himself.

“Rafe’s our business,” he said to Jillan at his back. “You understand me. Not me-Rafe. The other one. They can still hurt him. We’ve got to do something.”

“You got an idea?” she asked. No protest. That other Rafe was her brother too, the living one. “You got an idea?”

“No,” he said, “just a priority. Paul’s no worse off than we are. No better either. But our brother—” It was easier to think of Rafe that way. “They’re going to some trouble in his case. They saw to it that we found him. Didn’t they? That wasn’t accident.”

“There’s still the outside chance, like Rafe says—they’re not altogether hostile. Maybe we can’t figure the way they think. Maybe they’re too different.”

He twisted on his knees and looked back at her, snatching up a hope from that innocence of events. “I met one,” he said. “It wore your shape.”

Jillan blinked rapidly in shock, stared at him, seeming then to put things together.

“I figure you’d better know that,” he said, “so you don’t trust everything you see. It hurt. Quite a bit. Like at the beginning. It’s still got us here, wherever here is.”

The shock was real in her eyes. He saw that.

“Paul and Rafe,” she said, putting that together too. “It can get at them that way.”

<> was pleased in <>’s acquisition. It had been a question whether to shock Rafe Two with any kind of contact, any apprehension at all of his circumstances before securing his template, but <> had decided in the affirmative. The second Rafe-mind’s difference was precisely, after all, its knowledge, its adjustment to the environment more extensive than Rafe One’s. And the Jillan-face provided a certain insulation in the contact.

<> tried out what <> had gained, this Rafe with a little bit of knowledge where he was and what he was. The flexibility was greater. <> had hoped for that.

The solitude was worst, the long, gnawing away of expectations until the loss of the most dreadful fear seemed like the parting of a cherished possession, leaving increasingly remote and strange possibilities.

One could only pace so much, eat so often, meddle with the few active circuits Lindyhad left just so many hours, and bathe and sleep and bathe and sleep and make-work at the console, like the visual analysis of stars, the infinite working of infinite problems, calculation of space and acceleration and distances given things that would never, from his vantage, ever be true. But those hypotheses filled the mind and kept it focused, for a little while, on sane outcomes.

Rafe worked at guesses, had pegged several high-magnitude stars, two of which were conspicuous, almost touching. He tried one and another theoretical perspective on them, tormented himself with hopeful and despairing suppositions.

“Hey!” he shouted at the winding corridor more than once, frustrated and desperate. But no sound came back, from either direction.

He called the others’ names; he called his own, and had nothing but silence.

“You can’t take them away,” he muttered to himself, to God, to whatever ran this place, and bowed his head on the console. Finally, which he had never yet done, he truly mourned his dead and sobbed hysterically.

Even that wore thin. There was only so much grief, so much anger, not even so much as when he and Jillan were orphaned. Then there had been guilt—a child’s kind of guilt– Maybe if I’d been good they’d be alive—

It’s my fault. I should have loved them more—

There was no guilt here. Not with Jillan and Paul. He sat there with the last of the tears still cold on his face and judged that whatever mistakes they had made, they were paying for all of it together; Jillan and Paul’s being dead was not final but drawn-out, shared, a life-in-death which still could make jokes about its state, shed tears for itself, know fears for the future. The same thing waited for him, he reckoned, when whatever-it-was got around to his case.

It’s going to do that soon; they don’t want to watch what happens to me.

Or maybe they’re just gone. Turned off, of no more use.

No pain that way, at least.

And at last, all but sobbing in self-pity, he thought: But Rafe’s afraid to die.

He shuddered away from that entanglement and wiped his face with both his hands until the tears went down.

He thought of taking another long, long walk. His bruises had gone to livid green by now. He was stronger. He might take food, fill his pockets with it, use a plastic bag for a canteen—just walk, walk until he ran out of everything and those in charge had to do something about him, either meet him face to face or let him die.

But: Come to the ship,he had told his doppelganger. Perhaps their time sense was different. Maybe for them it was only a little while. If he left they might come and he would never know.

He flung himself down against the wall where he often sat and just stared at Lindy’s remains, not looking down the corridors which led into the dark.

“Rafe,” his own voice said.

He started half to his feet, braced against the wall, levered himself the rest of the way up. “Where have youbeen?” It came out harsh. He had not meant that. He was all but shaking, facing his naked self, which stood over against the dark of the corridor. “Did you find them?”

“Were you worried?”

“Was I worried? Don’t joke with me, man. I’m not laughing. Where are they?”

The doppelganger pointed, vaguely up and off beyond the walls. “There.”

“They won’t come?”

“Paul’s not coping well with this.”

He let go his breath, found his hands shaking, walked over to the console and sat down, firmly, in a place he knew. “Not coping well.”

“Not at all.”

“Jillan?”

“Better. She’s all right.”

“She’s with him.”

The doppelganger shook his head. “No. She’s not.”

“Cut the riddles. Where’s Jillan?”

“You’re upset.”

“God, what’s wrong– wrong with you?”

“Nothing’s wrong.”

“I know what it’s like—talking to myself; I do know; and you don’t follow my lead, not half right—” He put himself on his feet, leaning on Lindy’s board. “What are you?”

The doppelganger winked out.

“What are you?”Rafe screamed after it. He hit the useless board. “Jil-lan!”

And he sat down again, fell into his seat, trembling from head to foot.

“Clever,” said the doppelganger voice, off to his side.

He spun the chair, faced it where he sat. It stood over by the EVApod, dimmer, for the light was brighter there.

“You,” he said to it, gathering up his mind, “you’re the one I’ve been wanting to get in reach. Why don’t you come in here in person?”

“You want to kill me.”

“Maybe.” He sucked in a copper-edged breath and stood up. “Where’s my sister? Where’s Paul?”

“The physical entities? Dead. I tried to hold them. They died.”

“Dead. And their copies—” He did not want to admit how much it meant, but his knees were weak. He held onto the counter. “Do they still exist?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Bring them here.”

“I’ll let them loose again. Soon. I came to talk with you.”

“Why?” he asked, staring at the mirrored face before the blank visage of the EVApod. “To say what? What shape is Rafe going to be in? Do I get my own doppelganger back?”

“Yes. He’s safe. Is that a concern to you?”

He did not answer. It already knew weaknesses enough in him; it wore his doppelganger like a skin. He straightened his back and moved back to the console, turned around again. “Why not your own shape?”

“It would distress you.”

“You think this doesn’t?”

“A question of degree.”

“You’re not very like us.”

“No. I’m not.”

“You’re fluent.”

The image blinked. “It did take time.”

“How did you do it? How did you learn?”

“It would distress you. Say that I know you pretty well. From inside. I have a lot of your character right now.”

“And my memories?”

“That too.”

Rafe sank again into the chair, wiped a hand across his mouth to still the tic that plagued him. “And the way I think about things. I don’t suppose you’ve got that too.”

“There is a great deal of congruency at present. I’ve walled off some of myself; that’s the nearest analogue. I’m larger. Smarter. Far more educated.”

“Modest too.”

The doppelganger grinned.

“God,” Rafe said, “a sense of humor.” It sent a chill up his back, lent him other thoughts. “You can feel anything I’d feel. Do you?”

“Everything.”

“Like—loving them. Like that.”

“I do.”

He sat silent a moment, trying not to shiver.

“While I’m you,” it said. “In my full mind there are other considerations, I assure you. But within this configuration, I do love them. I understand perfectly what you mean.”

“You hurt us. Do you know that?”

“You can assume I remember. You don’t have to ask. You’re concerned about your safety, about the others. Let me destroy your illusions—”

“Don’t. Please. Don’t.”

“Not those.” The mouth twisted in a smile that left no residue of humor. “Not physically. ...”

had made a move. In the rest of <>’s mind, extended elsewhere in the ship, <> was well aware of this. gained access to apparatus could not otherwise have touched, and grew suddenly knowledgeable. It was the file on the intruders had gotten. gained sudden capability.

“Help,” (#) cried, rushing through the ship. “Help, help!”

“I told you so,” said <^>.

“... but I won’t tell you any more than you really have to know, if you’d rather not. I do mean to take you back.”

“Where?”

“To the star where I found you.”

“Is this a game?” Rafe’s heart was beating hard. “Why? Why do that?”

“A capsule with a beacon. They’ll pick you up, so this mind believes.”

“Why go to the trouble?”

“Why not? Harm to me? I don’t think they could.”

“You’re lying.”

There was long silence. “I understand your caution. Believe me. I do understand.”

“More humor.”

The mouth—his own—quirked up in a touch of mirth. “It doesn’t depend on your belief anyway.”

“You mean you’ll do what you like.”

“Aaaaiiiiiiiiii!”The sound began from far away; it roared closer and closer, speakers coming alive right overhead and fading away again, lightning-fast, blinding pain that hit and left: Rafe leaped up, trembling in its wake.

“Is that for effect?”

“That one’s mad,” the doppelganger said. “And a little upset right now. Don’t let it trouble you.”

“Sure. Sure I won’t. Cheap trick, hear? Like all the rest. Real cheap.”

“I’ll leave now. Something wants my attention. A minor thing. But I’ll put in somewhere soon at a human port and drop you off. Don’t worry for the jump drugs. I don’t know the composition of what you take. You don’t. But I can make you sleep; that should be enough.”

“Why does it matter? You’ve killed two people, damn you! Why does it matter now?”

“Because it’s easy,” the doppelganger said, and faded out altogether.

“Why?”he yelled after it until his voice cracked. He fell down into the chair, being alone again, in the silence. “Rafe?” he said aloud, querulously, hoping for the old one, the friendly one. “Jillan.” And last and with least hope: “Paul?”

No one answered. No one came. He was scared finally, finally terrified for himself, sitting and staring at nothing at all.

Going home, he thought. With human beings. Living ones. He did not believe it. He did not believe it loved. He did not believe it told the truth at all, or that it cared.

But there remained the possibility.

There remained the greater likelihood it had other motives. And it wore a human shape and used a human mind.

“Paul,” said, having penetrated the barriers <> had imposed about the stranger, having, momentarily, seized control of that territory. “Paul.”

And took the Rafe-image on self.

“You’re awake,” Paul said. “You’re awake.”

“Paul,” said, getting to ’s human feet. “Paul.” had that word down pat. snatched Paul in ’s borrowed arms and carried him rapidly out through barriers, along passages.

Paul screamed, and stopped screaming, simply clinging to what he feared, a logic that , in Rafe’s mind, understood with curious poignancy.

<> was too late to prevent the theft.

<> simply recreated the Paul-simulacrum of which <> had been robbed and left him asleep in a safer place, far inside <>’s boundaries.

Paul was not a serious loss. Paul had never adjusted and likely never would, but <> was still nettled.

“<> wish you success,” <> taunted , for <> had shed the Rafe-mind and felt differently about many things.

There was a division in Trishanamarandu-kepta. It had happened long ago. There was a place where did very much as pleased; and another where <> was the law. This was an agreement they had, one which made diversions, and <> cherished those.

Slowly, as <>’s humor improved, <> found a sense of ironical amusement in the theft, for the Paul-entity was unstable; and the Rafe-one had been unwaked and was now vastly disturbed. One did not intrude into a simulacrum and leave it intact.

“Do something,” <^> mourned.

“<> have,” <> said, for <> was still controlling the moves: had, being flawed, acquired two flawed entities, one flawed by nature, the other by invasion.

The important two were safe.

<> was awake again. All the way.

And the passengers scurried this way and that in panic, examining old alliances and likely advantage.

Only ((())) ranged the passages, wailing in ((()))’s madness. Perhaps only ((()))’s lower mind was left; perhaps some memory remained, what side ((())) had taken once. “Aaaaiiiieeeee,” ((())) cried. “Help us, help us all! O strangers, rescue us!”

“Paul,” Rafe said, who was not-Rafe, and something very strong.

Paul lay still and stared, heaving for breath in the all-enveloping dark while Rafe changed into something huge and slightly blurred. Paul flinched at this transformation and started to twist away, but Rafe’s touch was gentle, very easy, on his shoulder.

“You’re not him,” Paul said, and his own voice seemed very distant in his ears, as if he had been drugged. Everything seemed far.

“You’re safe,” it told him, which he wanted now desperately to hear. “You’re safe with me.” The strangeness had gotten to the all-enveloping point and battered at his mind; and just when it was at its worst, it promised him safety and protection. He was ready to believe.

“I have you,” the blurred shape said. The voice was Rafe’s, but strange and deep, like a motor running. “You’re very safe in my company. You don’t have to worry while I’m here.”

He let it hold him like a child. The voice sank to be one vast burr that filled everything, replaced everything. It touched him, mother-gentle, spoke to him in a language eloquent of protection; and he shut his eyes, trusting finally, because he could only sustain the fear so long in such closeness, in an existence in which he could not tire or sleep: the voice went on and on.

“Let go,” it hummed, “listen to me. You’re safe.”

“I’m dead,” he said. “What’s safe in that?”

“Not dead. Not truly. Not at all. You exist. You can come and go at will. You have long life ahead of you; and a comfortable one, with me. Be still, be quiet, rest. Nothing can reach you in my heart.”

“We don’t get hungry,” Jillan said. “I could wish we got hungry. I miss—” She shook her head and stopped, wisely.

Rafe stared at her bleakly, remembering many things he missed. At length he got up and tried the barrier again. It still held and he came and sat down again, letting his shoulders fall. There was no pretending with Jillan. Finally they had passed all embarrassment, all other pretenses; he was naked inside and out with Rafe and stopped minding: now he could be that way with Jillan, at least in most things.

“Beats station life,” he said, which was an old joke with them, that anything did. Even dying.

“Got ourselves a ship,” she said, rising to it valiantly, but the grief never left her eyes. Paul, Paul, Paul,they said, wrath and divided loyalties.

“Got ourselves a big one,” he said.

“What we have to do,” she said, “we find our way to controls—in our android shapes—and then we take this thing.”

“Deal,” he said.

But they sat there, with a barrier about them. With Paul missing, and neither of them made guesses about Paul.

He’ll find a way to rescue us,Rafe thought, trying to convince himself. He’s still loose, he’s smart—So’s Rafe—without modesty. But Paul can move through the ship....