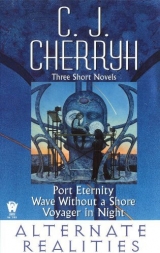

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

III

... and from them rose

A cry that shivered to the tingling stars,

And, as it were one voice, an agony

Of lamentation, like a wind that shrills

All night in a waste land, where no one comes,

Or hath come, since the making of the world.

Idon’t like to think of that time, and it was a long, long while before it dawned on me that I could move, and draw myself back from the void where I was. Things were all distorted. It seemed I could see through the hull, and through myself. Sometimes the chaos was red and sometimes the red became black and red spots crawled here and there like spiders. I cried, and there were other sounds that might be other voices, or the Maidherself still screaming.

Then like in the time before I left that white place where I was made, I had to have something to look at, to control the images, to sort truth from illusion, and I concentrated simply on getting my hand in front of my face. Knowing what it ought to look like, I could begin to make it out, bones and veins and muscles and skin. Not red. Not black. My own true color. I concentrated on it until it took the shape and texture it ought to have, and then I was able to see shadows of other things too, like the deck, and the rest of my own body lying there.

“Gawain,” I cried, and by concentrating on shapes I could see the controls, and Gawain, who looked dead hanging in the straps; and Modred, who lay on the floor ... his restraint had given way, as mine must have, and it should have broken my ribs, but it had not ... there was, at least, no pain. Modred was trying to move too, like something inky writhing there on the deck, but I knew who it was, and I crawled across the floor which was neither warm nor cold nor rough nor smooth ... I made it and got his hand, and hoped for help, because Modred was frightened by nothing, and if there was any of us who had a cold enough mind up here to be able to see what to do, I had most hope of Modred.

“Hung in the between,” he said. “I think we’re hung up in the between.”

His voice did strange things in my head, echoed round and round as if my brains had been some vast room. For a moment I didn’t want to look down, because there wasa Down and we were still falling into it. Gawain had to get us out of this; that was all I could think of, and somehow Modred was pulling himself to his feet and heading in Gawain’s direction. I scrambled up to follow him, and stood swaying with one foot on one side of a chasm and the other foot on the other side, stars between, the whole flowing like a river in born-men’s Hell, all fire and glowing with the stars like brighter coals. Don’t move, my brain kept telling my body, and I didn’t for a moment. I stood there and shut my eyes.

But there is an advantage in being what we are, which is that wherever we are, that’s what is, and we don’t have such problems as some do, trying to relate it to anywhere else. I was upright. I set one foot out and insisted to feel what was under it, and after that I knew that I could walk. I moved after Modred, though the room kept shrinking and expanding insanely, and sometimes Gawain was very far away and sometimes just out of reach, but two-dimensional, so that he seemed pressed between two pieces of glass, and his beautiful hair hanging down at an unconscious angle seemed afire like the river of stars, streaming and flowing like light.

“Gawain!” Modred shouted, all distorted.

“Gawain!” I shouted too.

Gawain finally began to move, slow reaching of an arm which was at the moment two-dimensional and stretched all out of proportion. He tried to sit upright, and reached for the boards or what looked like an analogue of them in this distortion of senses, a puddle of lights which flowed and ran in swirling streams of fire.

He’s there, I insisted to my rebel senses, and he began to be solid, within reach, as I knew he had to be. I grasped Modred’s arm and reached for Gawain’s, and Gawain twisted around and held onto both of us, painfully tight. “What you want to see, you cansee,” I said. “Don’t imagine, Gawain. Don’t imagine.”

He was there, all right. I could feel him heaving for breath, and I was breathing in the same hoarse gulps, and so was that third part of us, Modred.

“We’ve been malfunctioned into jump,” Modred said, carefully, softly between gasps for breath. Voices distorted in my ears, and maybe in his too. “I think we’re hung up somewhere in subspace and there’s no knowing what happened back there. We could have dragged mass with us into this place. We could have dragged at the sun itself. I don’t know. The instruments aren’t making sense.”

“Lady Dela,” I said, thinking about her caught in this disaster, Dela, who was the reason for all of us existing at all.

“No drugs,” Gawain murmured. “We’re in this with no drugs.”

That frightened me. We drug down to cope with the between of jump, that nowhere between here and there. But we were doing it without, if that was where we were ... and like walking a tightrope across that abyss, the only hope was not to look down and not to lose our balance to it. One necessity at a time. “I’m going for lady Dela,” I said.

“You’ll get lost,” Gawain protested, because the floors were still going in and out on us, taming reds and blacks and showing stars in the middle. “Don’t. If we ripped something loose back there, if those corridors aren’t sound. ...”

“Use com.” That was Modred, clearer headed than either of us. Modred passed me like a great black spider, and reached into the pool of lights, perhaps able to see them better because he knew what ought to be there. “Lady Dela,” he said. “Lady Dela, this is Modred on the bridge. Do you hear me?”

“Modred!”a voice wailed back like crystal chimes. “Help!”

“Lady Dela!” I said. “Make up your mind to see ... can you see? Look at something familiar until it makes sense.”

“Help me,” she cried.

“Do you see anything?” Gawain asked her. “Modred says we’ve had a jump malfunction. I agree. I think we’re hung up in the between, but what I have on instruments looks like the ship is intact. Do you understand me, Lady Dela?”

“Get us out!” she screamed.

“I’m trying, lady. First I have to know where we are.”

And to anyone who was thinking, that answered it, because even I knew enough to know we weren’t anywhere at all that our instruments were ever going to make sense of.

Com was open. There were voices in from all over, like tiny wailings. I could make out either Lynette or Vivien, and Percivale and Lancelot. And Griffin, giving orders.

“I can’t,” Gawain was saying. It was to his credit that he didn’t blank, nor did Modred; but this was not an emotional crisis, this was business, and we were in dire trouble with things to do—if we could do them under these conditions.

I shivered, thinking that I had to navigate the corridors and somehow get to lady Dela. I clung to something solid on the bridge, trying to remember what the hallways looked like down to the last doorway, the last bolt in the walls, because if I forgot, I could get very, very lost.

“We may have been here a while,” Modred’s voice came to me out of the surges of color that filled my vision, and I made him out, black and slim, in front of the pool of lights. “Our senses are adjusting to interpret by new rules. If we’re very careful, we should be able to keep our balance and find our way about.”

“How long?” I asked. “How long can we have been here?”

“We play games with time and space both,” Gawain’s near-far voice returned, loud and soft by turns. “Jump ... does that. Only we haven’t come out of it. We’re somewhere in subspace. And in the between, haven’tis as good a prediction as we can make.”

“Time,” said Modred, “is the motion of matter; and relatively speaking, we’re in a great deal of trouble. We don’t know how long. It means nothing.”

I grasped that. Not that I understood jump, but I knew that when ships crossed lightyears of distance by blinking here and there through jump, there had to be some kind of state in between, and that was why we took the drugs, not to have to remember that. But of course we were remembering it now: we were sitting in it, or moving through it, and whether time was stretched and we were living all this in seconds or whether we were really what Modred and Gawain said—hung—my mind balked from such paradoxes Theyjuggled such things, Gawain and Modred and Percy and Lynn, but I had no desire to.

All at once Lynette came wading through the red and black toward us, stained with the glow that was everywhere, and walking steadily. It was a marvelous feat, that she had gotten from the lower decks up here, and gotten to her post, but there she was, and she pushed me out of the way and sat down in the phantom of a chair, reached into the pool of lights and started trying to make sense of things.

“Percy’s coming,” she said. And he was. I could see him too, like a ghost striding across the distances which behaved themselves better than they had been doing a moment ago. Everyone was getting to their posts, and I knew mine. I stood up and reached out my hands so that I wouldn’t crack my skull and I walked, having less trouble about it than I feared. Spatial relationships were still giving me trouble, so that things looked flat one moment and far away the next, but I kept my arms out for balance and touched the sides of the corridors when I could, shutting my eyes whenever the chaos got too bad.

It meant going far back through the ship, and the corridor writhed like a transparent snake with a row of lights down its spine. At times I shut my eyes and felt my way, but the nerves in my hands kept going numb from time to time and the walls I couldn’t see felt sticking-cold and burning hot if I let them.

But they were only feelings, lies my senses tried to tell me, and once and long ago I had lived in that white place where only the tapes are real—where I got so good at seeing that I could make pictures crawl across the walls of my cell just as if the tapes were really running. Reality—that doubtful commodity that I had learned to play games with a long time ago, because my own reality was dubious: I knew how to make up what I liked; and I had flown and flashed from world to world with my lady Dela; and I had sat in country meadows under blue skies at Brahmani Dali and talked to simpler-trained servants who thought the blue was all there was, and who patted the ground and said that thatwas real—but I knew it wasn’t. Their up and down was all relative, and their sitting still was really moving, because their world was moving and their sun was moving and the whole relational space of stars was spinning out in the whirlpool eddy of thisgalaxy in the scattering of all galaxies in the flinging-forth that was time.

But their time, these servants’ time, was the slow ticking away of decay in their cells, and in the motion of a clock toward the date that they would be put down, and their reality would end.

They would have gone crazy here, walking down a heaving belly of a snake in that place which somehow bucked the flinging-outward that made all they knew; and Idid not break down, being sensible, and having an idea from the beginning that it was all like the tapes back in the labs, that told our senses what to feel and do and pay attention to. There was no sense being emotional over it: new tapes, new information.

So I kept telling myself, but my nerves still would not obey the new rules and my brain kept trying to tell me I was falling and my stomach wanted to tell me I was upside down.

I sent strong orders to my eyes. The wall straightened itself marvelously well when I really bore down on it, but shadow was really shadow, like holes into nothing. Like snippets cut out of the universe. I saw space crawling there, with hints of chaos.

Left turn. I felt for a doorswitch, wondering if anything was going to work with the ship where it was, but com had worked; and the instruments back in controls were still working, even if they picked up nothing sensible. And the door did open.

I kept going, down a corridor which seemed nightmarishly lengthened. The door at my right was open, and these were my lady’s compartments. I held out my hands and walked along quite rapidly now, felt my way through the misshapen door.

Someone was sobbing, a throaty, hoarse sound that moaned through the walls: that guided me. I tripped over something that went away like chimes, over and over again, caught myself on something else I could not recognize and tried to get my bearings. There were points of light, shimmers of metal—the artificial flame lamps and the old weapons that Dela loved. That puddle of color up/down? was one of the banners, a lion in gold and red and blue. And beyond that puddle was a doorway I knew. I went to it, and through the corridor inside, to the open door of her bedroom ... a lake of blue, a great midnight blue bed, and a cluster of shapes amid it.

My companions ... they had reached her. Lance sat there holding my lady in his arms, and Viv huddled next to him.

“Who is it?” my lady wailed.

I came and joined myself to the others, and we held and comforted her. “It’s all right,” Lance kept saying. “It’s all right.” And I: “You know our faces. Lookat us and everything will be what you tell it to be. It’s Elaine. Elaine. Tell your eyes what they should see, and make them believe it.”

“Elaine.” Her hands found my face, felt for it, as if to be sure. “Go. Go help Griffin. Where is Griffin?”

“He’s well,” I said. “I heard him giving Wayne orders.”

“Go,” she pleaded, so abjectly I knew she was upsetting herself. I gathered myself up and steadied my own nerves, felt Lance’s hand clinging to mine. I pulled loose of it, reached out my own toward the doorway and found it—better, much better now that I had walked this way once. I forced the room into shape and got to the corridor, felt my way along it past the library doors on the left and toward Griffin’s door at the end. I got it open and a voice bellowed out at me, echoing round and round in my head.

Griffin was sick, blind sick and raving. I found the bed, found him, and stripped sheets to do what I could to comfort him. He lay on the mattress and writhed, and when I tried to make him be still he fetched me a blow that flung me rolling. It was some few moments before I could clear the haze from my eyes again, with the floor going in and out of touch with my hands, but I made it behave itself, felt the carpet, made myself see the texture of it. When I could sit up and rub the starbursts from my eyes, Griffin was sitting up and complaining; and demanding Gawain get us out of this place.

“Can’t, sir,” I said, hanging on the back of a chair. “We’re in the between and we don’t know where we are.”

“Get away from me,” he said. I couldn’t, because my lady had told me to stay, but I pulled myself around to the front of the chair and sat down there with my knees tucked up in my arms, listening to Griffin swear and watching him stumble about the room knocking into furniture.

Eventually he discovered what we had discovered already, that he could control his stomach, and see things, and he finally seemed to get his bearings. He stood there the longest time, holding onto the dressing counter and looking at me with an expression on his face that clearly said he had not known I was there. He straightened back, stood up, felt with spidery moves of his hands toward the wall close by him. Ashamed. That was clear. And that surprised me despite everything else, because it was the first time Griffin had ever looked at me, really seemed to notice whether I existed. He turned away, groped after the bed and threw the remnant of the bedclothes over the side. Then he sat down and leaned his head into his hands, in brittle control of things. I think it took Griffin longest of all of us because he was used to having his own way, and when the whole world stopped being what suited him, it really frightened him. But our lady Dela, who lived in fantasies, she was mobile enough to attack the corridors, and showed up unexpectedly, using Lance for her help, and with Vivien trailing anxiously after.

“Worthless,” lady Dela snapped at me, finding me still perched on a chair and her precious Griffin evidently neglected, sitting on the bed. I started to warn my lady when she swept down on Griffin, but at least he refrained from hitting her. He cursed and shook her hand off ... her precious Griffin, I thought, who had never once asked about Dela.

“Out,” Dela ordered me, so I got up and left her to her ministries and her lover, finding the floor a great deal plainer than it had been and the walls at least solid. I walked out, and she cursed Lance and Viv too, telling them they ought to be about their proper business, so I waited for them outside, and caught Lance’s hand and held onto it for comfort when they came outside the door. What we were supposed to be doing, what our business was now, I had no least idea. Lance looked vastly shaken. Vivien looked worse than that, her eyes like one vast bruise, her hair disheveled, her fingers locked like claws on Lance’s other arm, as if she were afraid he would dissolve at any moment. I reckoned that Vivien, who was so very good at books and figures, really had the least concept of all what had happened to the Maidand to her; she was narrow, was Viv, and so long as her accounts balanced, that was enough. Now they did not.

“I think maybe we should get Viv to bed,” I said, and Lance pried her fingers loose and took her hand. We put our arms about her and guided her between us, all the long confusing way back to the lift; and that was the worst, that little loss of vertical stability after all the rest had been ripped away from us. Viv simply moaned, too dignified to scream, and leaned on us. We got her out again at the bottom and back to the crew quarters. She was better when we had put her into bed, not troubling to undress her. I tucked the sheet up over her and Lance patted her forehead and got her a drink, holding her head with great tenderness despite all his own distress. It seemed strange how Lance and I managed better than Dela and Griffin and even Vivien, who until now had managed our lives and told us what to do. But we didn’t have to cope with the whys and the what-nows, just do little things like walk the halls and keep ourselves on our feet. The ones I least envied in this calamity were the Maid’s crew, who were up in controls trying to figure where we were and even when—with no reference points.

IV

... but Arthur with a hundred spears

Rode far, till o’er the illimitable reed,

And many a glancing plash and sallowy isle,

The wide-wing’d sunset of the misty marsh

Glared on a huge machicolated tower....

Hour by hour, if that was really a word we could use any longer, the world grew clearer, and Vivien confessed she would live. Then came peevish orders from my lady, who complained she was deserted by the whole staff: she wanted Lance—which meant Griffin was better, I reckoned, since she sounded more angry than hysterical.

Lance went off in his pained despair, called up there to be near Griffin, which he hated, and with Dela, which was all he ever wanted. That left us with Vivien in the crew quarters then, in disfavor, I suspected. Vivien had drifted into quiet, exhausted, and we had given her a little sedative we had had ready for jump, belatedly, but it let Viv rest, not quite out, not really tracking on much either. And in a ship the walls of which were none too stable yet in my senses ... the lonely quiet seemed to put me all too far from everyone else. I was also conscious suddenly that my stomach was terribly empty. If time had gone as wrong as we thought it might have, then it might have been a long while that we had not wanted food or water, but now it hit me all of a sudden, so that I found my limbs shaking, as if all the demands of some long deprivation were coming due.

And sure enough about the same time came Lynette’s voice ordering one of us to get food up to the bridge as quickly as we could, claiming they felt faint. I was not sure that my lady Dela and particularly Griffin or Viv wanted to see food yet, but I staggered down to the lift and out on the lowermost level to the galley, and tried to put food for all of us together, out of the shambles our wild careering into jump had made of the place.

Then Vivien showed up in the doorway, a little frayed about the edges, it was true, muzzy with the drug, but moving along without touching the walls. She said nothing. Her face was set and determined with more fortitude than I had reckoned existed in Viv, and she had put most of the strands of her hair back into place so that she looked more herself. She was hungry, that was what: discomfort had gotten her moving again the same way it had sent her to bed, and without a by-your-leave she started into one of the trays. So had I, truth to tell. I had been stealing a bite and a drink while I was making the rest, because I wanted to stay on my feet to do it.

“Do they know anything yet?” she asked.

“No,” I said. I refrained from adding that they weren’t going to, not to pull the props out from under Viv a second time. The intercom came on: “My lady Dela wants a breakfast sent up,” Lynette advised me, from the bridge, and I frowned: it was a lunch I had just put together. “If she wants it quick,” I said back, “she can have a lunch that is ready. She’d have to wait ten minutes for the breakfast.”

A delay. “She wants it now,” Lynette relayed back. “Anything.”

“It’s coming.” I stacked up the trays in a carrier, along with the coffee, looked up at the sound of a step in the corridor. Lance showed up and leaned there in the doorway, a shadow of himself. “Tray for you too,” I said. “Here.”

“She’s sent for breakfast.”

“I got the call. She takes what she can. Here.” I put a hot roll into his hand and he ate that while I finished stacking the other carrier for the crew. I gave Dela and Griffin’s carrier to Lance.

“I’ll go,” Vivien said, swallowing down her milk. She dried her hands, wiped possible wrinkles from her clothing. “I’ll go with you.”

Lance nodded, the carrier in one hand. He left, and Vivien went with her arm locked in his ... up where Dela was. I might have gone. I might be where there was Dela to make sense of things. But I remembered the other carrier and Lynette, the whole crew up there, and then I realized what Vivien had done, leaving the work all to me.

I picked it up, grabbed another roll for myself and carried the box to the lift, rode it up, swallowing a mouthful of the roll and trying to keep my stomach down as well.

They were anxious for the food when I arrived, shadow-eyed and miserable. Percivale came and took the carrier from me and passed it round, looked puzzled at me when there were not enough. “I had a roll down below,” I said, settling on a counter edge, still chewing the last of it and knowing it must sound as if I had fed myself first of all. “While it was in the oven.”

They said nothing, but peeled back the covers and drank out of cups that shook in their hands ... working harder than the rest of us and using up their reserves far faster, I thought, wishing I could have hurried it. As for me, I could go now to my lady, find what comfort there was now in her—but that was none, I thought. The screens all looked full of the same bad news. “Where are we?” I asked, after lingering there a moment, after they had at least had a chance to get a few swallows of the food down. “What’s happening? Can you tell anything?” I thought—if there was any hope, I would like to take it to Dela. But they would have done that: they would have called her at once, if there were.

“We’re nowhere,” Lynette said sourly.

“But moving,” said Modred.

The idea made me queasy. “Where?”

Modred waved a hand at the screen nearest Percy. It showed nothing I could read, but there were a lot of numbers ticking along on it.

“We’ve tried the engines,” said Gawain. “We’re moving, but we don’t get anything. You understand? We’ve tried to affect our movement, but what works in realspace won’t work here at all, wherever here is. We’ve tried the jump field and it won’t generate. We don’t know whether there’s something the matter with the vanes or whether we just can’t generate a field while we’re in this space. Nothing works. We’re without motive power. No one’s ever been here before. No one knows the rules. Jumpships only skim this place. We’re init.”

I nodded, sick at my stomach, having gotten the bad news I had bargained for.

“But there’s something out there,” Percivale said. “That—” He indicated the same screen Modred had. “That’s a reading coming in, relative motion; and it’s getting stronger.”

I thought of black holes and other disquieting things, all impossible considering the fact that we were still alive and functioning, and kept arguing with myself that we had been safe where nothing like this should have happened, in the trafficked vicinity of a very normal star—which might or might not be normal now, the nasty thought kept recurring. And what about all the rest of the traffic which had been out there with us when we went popping unexpectedly into jump, presumably with some kind of field involved, which could tear ships apart and disrupt all kinds of material existence. Like planets. Like stars. If it were big enough.

“How—fast—are we moving?” I asked.

“Can’t get any meaningful referents. None. Something’s there, in relation to which we’re moving, but the numbers jump crazily. The size of it, whether the thing we’re picking up is even solid in any sense ... or just some ghost ... we don’t know. We get readings that hold up a while and then they fall apart.”

“Are we—falling into something?”

“Can’t tell,” said Modred, with the same calm he would have used ordering another cup of coffee.

I sat there a long time, letting the fright and the food settle. By now to my eyes the ship interior had taken on normal aspects, and my companions looked like themselves again. I reckoned that the same sort of thing must be happening with all of us, that about the time our bodies began to trouble us for normal things like food, our sensory perceptions were beginning to arrange themselves into some kind of order too.

We wouldn’t starve, I thought, not—quickly. The lockers down there had the finest food, everything for every whim of my lady. The best wines and delicacies imported from faraway worlds. An enormous amount of it. We wouldn’t run out of air. The interior systems were getting along just fine and nothing had shut down, or we would have had alarms sounding by now. Bad air or starving would be easiest, at least for us, who would simply blank and die.

I was terrified of the thing rushing up at us, or that we were rushing down into, or drifting slowly, whatever it was that those figures meant ... because we had just had a bad taste of being where we were not designed to be, and another fall of any length did not sit well with my stomach.

But we could take a long time to hit and it seemed there was nothing to be done about the situation. I stood up, brushed my suit out of wrinkles. “I’m going to see my lady,” I said. “Is there anything I can tell her?”

“Tell her,” Gawain said, “we’re trying to keep the ship intact.”

I stared at him half a beat, chilled cold, then left the bridge and walked back out through the corridors which now looked like corridors ... back to my lady’s compartments.

Griffin was there when I arrived. They had gotten him up and mobile at least, into the blue bedroom, to sit at a small table and pick at the food. My lady sat across from him. I could see them through the open door. And Viv and Lance waited outside the bedroom doors, Vivien sitting on a small straight chair which had ridden through the calamity in its transit bolts. Lance was picking up bits of something which had shattered on the carpet, and some of the tapestries were crooked in their hangings.

I sat down too, in a chair which offered some comfort to my shivery limbs. Lance finished his cleaning up and took the pieces out, came back and paced the floor. I did not. I sat rigidly still, my fingers clenched on the upholstery. I was thinking about falling into some worse hole in space than we had already met, feeling that imagined motion of those figures on the bridge screen as if it were a hurtling rush.

“Where are we?” Vivien asked, my former question. Her voice was hushed and hoarse.

“In strange space,” I said. And then, because it had to be said: “The crew doesn’t really expect we’re going to get out of it.”

It was strange who came apart and who did not. Lance, who was always so vain and so worried about his appearance and his favor with my lady—he just stood there. But Vivien sat and shivered and finally blanked on us, which was the best state for her, considering her upset, and we did not move to rouse her.

“I think,” Lance said, looking on her sitting frozen in her chair, “that Vivien planned to live a long, long time.”

Of course that was true. Poor Vivien, I thought. All her plans. All her work. She stayed blanked, and kept at it, and finally Lance went over to her and patted her shoulder, so that she came out of it. But she slipped back again at once.

“It’s a ship,”Percivale’s voice broke over the intercom uninvited. “It’s another ship we’re headed for.”

That brought my lady and Griffin out of their bedroom refuge, all in a rush of moved chairs. “Signal it!” my lady ordered, looking up at the sitting room speaker panel as if it could show her something. “Contact it!”

Evidently they were doing something on the bridge, because there was silence after, and the lot of us stood there—all of us on our feet in the sitting room but Viv. Lance was shaking her shoulder and trying to get through her blankness to tell her there was some hope.

“We’re not sure about the range,” Modred reported finally. “We’ll keep trying as we get nearer.”

Griffin and lady Dela settled on a couch there near us, and we turned from Vivien to try to make them comfortable. Lady Dela looked very pale and drawn, which with her flaxen hair was pale indeed, like one of the ladies in the fantasies she loved; and Griffin too looked very shaken. “Get wine,” I said, and Lance did that. We even poured a little for ourselves, Lance and I, out of their way, and got some down Vivien, holding the glass in her hand for her.