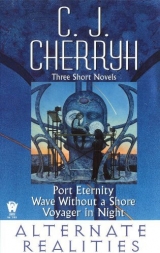

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

XIII

This night a rumor wildly blown about

Came, that Sir Modred had usurp’d the realm

And leagued him with the heathen. . . .

... Gawain, surnamed The Courteous, fair and strong,

And after Lancelot, . . . a good knight, but therewithal

Sir Modred’s brother, and the child of Lot,

Nor often loyal to his word ...

Iran, and was too late for the lift. But Gawain was not: he and Lance were headed topside together, in what state I hated to imagine. Percy and Lynn came running after, and caught me up by the time the lift, empty, had come down again.

“Modred’s his partner,” Percy said, meaning Gawain’s, meaning where loyalties lay. Lynette said nothing; it was like that between them, I thought, while the lift shot us up topside: that Percy and Lynette worked together, were together, that while it was Gawain most often Lynette bedded with—blithe and light Gawain—it was Percivale who worked with her, close, close as ever we could be; like Modred and Gawain.

The door opened and let us out: I ran, but Lynette and Percy ran faster, for the doors where already we heard shouting.

The doors were closed. Locked. Of course, locked. Modred knew his defenses.

“Open up,” Lance shouted, and slammed the sealed door with his fist. But he was staff: he had no right to command the crew. And Gawain stood there doing nothing to help until Lynn and Percy came running up ahead of me. “Order him to open,” Lance asked of them, and Lynn: “Modred,” she called. “Modred—” But gently, reasonably.

From inside, no answer.

“Ask him,” Percivale asked of Gawain. “He’ll listen to you.

“I doubt it,” Gawain said. And so there we stood, the several of us—oh, it was terrible the look of us, of Lance and Gawain face to face and glaring at each other—

“It can’t happen,” I said, tugging at Lance’s arm. “O Lance, go and fetch my lady. He’ll listen to her. Please. We’re what we always were. We can’t have changed; and he can’t. O run, run and tell her. Modred’s not well.”

He yielded backward to my tugging at him—like tugging at a rock, it was; but I put myself between the two of them—him and Gawain. Too proud to back very far: I saw Lance’s eyes. “Percy,” I said, “go.”

And Percy ran. The lift had worked again, down the corridor. Vivien was there, and I could see she was satisfied ... O the malice, the bitter, bitter malice that her makers never put into her, but the place had given her, and the ruin of all she was.

“What,” she said, “has he shut you out then?”

“Be quiet,” Gawain said. “We don’t need you here.”

“Modred,” Lynette called, gently, using the com by the door. “Modred, are you all right in there?”

“He’s gone over the brink,” Lance said. “Modred, come out of there. We’ve sent for my lady. She won’t be amused.”

Silence from the other side.

“Maybe something hashappened to him,” I said, fearing more and more. “We aren’t right to think the worst of him.”

“He hears us,” Lance said. “His partner knows what he’s doing. I’d bet on it.”

I looked at Gawain, whose beautiful face was flushed with anger, whose eyes had no little of fear: Lance could beat him, and there was no doubt of that.

“Wayne,” Lynette said, “you covered for him? You knew?”

“Should I let you kill yourself and the rest of us?”

Lance reached out very deliberately and took Gawain’s arm, brushed me aside as if I had not been there. “We have orders,” Lance said.

And might have said more, but Percy came hurrying back to our relief. “She’s coming,” Percy said, “my lady and Griffin—” He stopped, transfixed at this sight we made, this laying on of hands that we had never done to each other. But we had nerved ourselves to fight, and had nothing of substance to fight but each other. Lance let Gawain go, further argument abided. And down the hall came Griffin and my lady, in their nightrobes, Griffin with his hair wet from the bath, my lady all a flurry of loose blonde hair and laces and her eyes—oh, my lady’s eyes, so full of fright. She knew, sheknew how wrong we had gone: but Griffin’s face was ominous, all threat and anger. He came right through us, punched the com button, slammed his great fist on the door.

“Modred,” he said. “Enough of this nonsense. Get this door open.”

And more silence. I found myself with my hands clasped before my mouth, like praying. O Modred, I thought, Modred, you can’t, you can’t defy him. O Lance, O Gawain, do something.

“Modred!”Griffin yelled, another slam of his fist.

And my lady slipped past and leaned up to the com. “Modred. You know my voice.”

A delay. “Yes, lady Dela.” Like himself, it was, all quiet and untroubled as Pass the salt, please.

“Modred, I want this door open.”

“In a moment, my lady.”

In a moment.O Modred. Something shivered through me. We had all gotten very still, even Griffin. My lady looked distraught and then gathered herself.

“What are you doing, Modred?”

Silence.

“Modred, what do you think you’re doing?”

Silence. A long silence. “That programof his—” Griffin said. “That program he wanted to use—”

“Modred,” lady Dela said. “I want this door open right now. I want you to shut down what you’re doing and come out here. No argument.”

A longer silence.

“We’ll have to get the cutters,” Griffin said.

“Modred. Did you hear that? Are we going to have to do the Maiddamage on account of you? Open the door.”

It opened, so unexpected it jolted all of us—whisk! and he was standing there facing us across the bridge, a black figure against the comp lights and the screens that showed nothing they had not showed before.

“Get him out of there,” Griffin said, and Lance and Percy moved in, took Modred’s arms—nothing. No countermove. Modred gave way to them and would have let them take him out now, but Griffin barred the way, and the rest of us, and lady Dela.

Griffin put his hand in the middle of Modred’s chest and stopped him face to face. “What have you done?” Griffin asked.

“Discover that,” Modred said, “sir.”

“Modred,” Dela said—not angry, not anything but stunned. Modred looked at her then, and even he had to feel something: we’re made that way. It had to be pain all the way to the gut, every psych-set torn. But Modred had no nerves. His expression hardly varied. “My lady Dela,” he said equably, “I’ve sent it out, all of it.”

“Contacting that thing?”

“It’s done.”

“And what did you get from it,” Griffin asked. “Anything?”

“I was working on that. If you’ll let me continue—”

I don’t think he even understood it was effrontery.

“Not likely,” Griffin said.

“How could you do a thing like this?” Dela asked. “Who gave you leave? Did I?”

“No,” Modred said.

“And what have you sent out? Whathave you told it?”

“Mathematics. Chemistry. Our chemistry ... in symbolic terms.”

“Then it knows what we are,” Griffin said.

“As well as I could state it.”

“Get him out of here,” Griffin said. “Lock him somewhere.”

“Sir,” Lance said. “Gawain knew.”

Griffin looked at Gawain, and Gawain’s face went white.

“Then we’ll be talking to you as well,” Griffin said.

“Sir,” Gawain breathed and bowed his head.

Griffin looked about at all of us then, and I felt my bones go cold. “Get him out,” Griffin said then and Lance and Percivale took Modred past me without argument from Modred. I stood, close to blanking, knowing what I had done.

“Staff’s dismissed,” Griffin said. “Go about your business. We’ll straighten this mess up. Now. Out. Crew stays.”

I fled, down the corridor after Vivien, disheveled as I was. My bones ached, somewhere inside the terror and the confusion: we had worked ourselves until we staggered with exhaustion, and now this—this, that was somewhere at the bottom of it my doing.

I went down and washed and put on clean clothes, because I knew there was no hope of sleep, Our night was over before it had started.

“See,” Vivien said, “how organized it all is. No one knows what’s afoot.” She looked up and about her, where the noise continued, maddening, lifted her hands to her ears as if that could give a moment’s relief. “They lost all our chances days ago.”

“Shut up,” I said, zipping my clean jacket and pulling my hair from the collar. “If you’re so efficient, go back to your lab.”

Oh. Cruel. Viv turned such a look on me that was hate and terror at once.

“Or do something outside yourself, Viv. Be something larger than you are. Think how to protect that lab of yours. Come up with something. Help us, for once.”

“Elaine the fair.”

“Don’t be trapped by it. By the tape. You don’t have to be. Oh, Viv—”

“Percy talks about God,” she said. Gleaming behind the hate in her eyes was outright terror. “‘ Hefound God,’ our Percy says. And what kind of thing is that for one of us? What’s for me? You’ve all gone mad ... and Percivale’s gone and Modred—What of this wouldn’t have happened without you? I think it’s funny. Oh, it’s a fine joke, Elaine.”

“Hush, be still.”

“What, be still? Me, who could work miracles in that stupid tape ... Let me do one enchantment and I’d be out of here, let me tell you, sweet Elaine.”

“Couldn’t it be we?” I asked. “It’s always I, isn’t it?” I went for the door. Stopped, hearing uncharacteristic silence at my back.

She might have been upset, I had thought. But there was that terrible anger on her face, a sullenness unlike Modred’s nerveless quiet.

“He talks about God,” she said. “We’re all rather above ourselves, aren’t we? Like Modred.”

She had stopped caring for living. That was the way she had coped with the shocks. I saw that suddenly, and it made me cold. She jumped from attacking Lynn to attacking Modred, to Griffin, to whoever had tried to do anything to change what was. Most of all she had me to blame, when the threat had gotten to the lab and the tape had gotten to her: that was twice she had had her functions shaken apart—and now there was just the tape, and her own defenses.

Percy talking about God and Modred turning on us—and Lance and Gawain at odds....

O God help us, I thought, which was unintended irony. We’re all lost in Dela’s dream.

And in it we faced our war.

They were busy on the bridge, Percy and Gawain and Lynette and Griffin and my lady Dela—there was nothing I could do there. They were busy trying to figure out what Modred had done on the bridge; but Modred was very good and I doubted they could find it at all if Modred had taken pains to hide it.

And Lance guarded the small room down the corridor which was a small cabin we had used on other voyages, where he had found to put Modred, I reckoned. Lance stood there, against the wall by the door, not moving, and looked tired beyond reckoning. “I can get a chair for you,” I offered. “Is there anything I can do?”

“I’m well enough,” he said, “but I’d like the chair, thanks.”

I brought it, out of Dela’s rooms, and set it down for him. He sank into it, with shadows round his eyes, with his big shoulders bowed. There was nothing anywhere to be happy about ... and still that hammering continued.

I knelt down, took Lance’s hand and looked up at him, which was the only way I could have his attention on me. It was focused elsewhere until then—somewhere insubstantial, maybe, on my lady, on our prospects. On what craziness brought him to lay hands on Gawain. I had no idea. His thoughts had grown complex, and they had never been that before. But he saw mebecause he had to, and his fingers tightened a little on my hand, cold and loose in mine until that.

“We’ve done all we can do,” I said. “Lance—it’s still all right. He can’t have done us that much harm. Let me talk to him, can I? I always could talk to him. I might make sense of him.”

“You don’t know what might be in his head.”

“I know you’ll be right outside,” I said in all confidence. His eyes flickered—it was a touch of pride, of what his shadow was. He wanted so much—so many things. For him a little praise was much.

“I think,” he said, “he got nothing at all to eat or drink yesterday: he might want that.”

Break Modred’s neck he might; but cruelty was not in Lance. He thought of such things. I nodded.

“I think he might,” I said, and got up and went off about that, while Lance kept his watch at the door.

So I came back from the dininghall stores with a sandwich and a cup of coffee, and Lance got up and let me through the door. Just a moment he stayed there, while Modred got up from the bed where he had been sitting, but Lance said nothing, and Modred said nothing, until Lance had closed the door.

“You haven’t had anything to eat,” I said.

“Thank you.”

As quiet as before, as precise and proper, his thin hands clasped before him.

“Modred, why did you do a thing like that?”

He shrugged. “Thank you for the food,” he said. I had not set it down. He meant I should leave, that was clear.

“Doesn’t it hurt?” I asked. “Haven’t you got any nerves at all?”

“If they make the bridge across, they might be right or wrong. But they don’t know. And it’s reckless.”

Modred—to talk about recklessness, after what he had done. I set the tray down. “Then why won’t you talk to them, tell them what you’ve done?”

“I don’t see that it makes any difference.”

“Youdon’t see. When did you see everything?”

Another shrug. No one attacked Modred. I stared into that dark-bearded face that frightened born-men and tried not to think of the tape, of that otherModred.

“Modred, pleasetalk to them.”

“The program isn’t locked,” he said. “They’ll have had no trouble accessing it.”

“You could have asked permission.”

“I did.”

It was so. I knew that he had done that again and again.

“And if I’m wrong,” he said, “there’s Lynette’s way; but if she’s wrong—there’s nothing left, is there?”

“You might be right. And if you are, come back, beg their pardons, talk to them.”

He shook his head, walked over matter of factly and investigated the tray I had brought. “Thanks for the food. I hadn’t time yesterday.”

“Whywon’t you talk to them?”

He looked up at me. There was a hint of pain, but he looked down again and unwrapped the sandwich, looking only tired.

“Modred.”

A second time he looked up at me. “They will never listen—to me—even when they should. Reason won’t work, will it—not against what a born-man wants to believe. I’ve seen that before now.”

“Do you understand—what it was in that tape Percy found in the locker?”

“Entertainment. A fancy. The logic on which this ship exists.”

And the Maidwas for him—the reason he existed. So it had gotten through to him. There was no reason in it. Modred had not even the nerves to be afraid: he was only trying to think it through and coming out with odd sums. He took a bite of his sandwich, a sip of the coffee. “It was kind of you to come,” he said.

“If you could explain to them—”

“I have explained to master Griffin. I don’t think he really understands. Or he looks at my face and stops listening.” His brow furrowed. “I’ve exhausted reason. There’s nothing else but what I did.” A second sip of coffee, and absently he turned his back on me and walked away.

“Modred, look at me. Don’t be like that.”

He turned back again. “I don’t precisely understand what kind of reasoning it is. Only that I’m not trusted. And that Griffin commands this ship.”

“He’s a good man.”

“But do you think he’s right?”

That was the logic that divided us ... We went by other things; and Modred only on his reckonings.

“I’m still following original instructions,” Modred said. “To get us out of this. Vivien has the right idea and none of you will listen to her either.”

“You said it can’t be done.”

“I said there was no escaping the mass. I said other things no one heard.”

“You mean talking to that thing.”

“It’s not attractive. It’s dangerous. You don’t like things like that. I know.”

“You left Gawain in trouble on your account.”

“Gawain did as Gawain chose to do.”

“Then you’re not alone. You can’t say no one believes in you.”

“Or the tape chose for him. He’s my ... brother ... in the dream. It’s a very dangerous thing, to see one’s whole existence, from beginning to end, isn’t it? I’m Modred. And not to be trusted. Even if I have the right idea.”

The door opened, abruptly. Born-men do such things, without a by your leave. It was Griffin.

“I’ll see you now,” Griffin said, “in the dining hall. Now.”

And Griffin left, like that, leaving the door open and Lance standing there.

I was afraid suddenly, seeing the look on Modred’s face, that was stark frustration—a born-man could do terrible things to us; there were all our psych-sets. There was all of that.

Modred set the tray and cup down, click, mostly untasted, and straightened his shoulders and walked out, past Lance without a look or a word. Lance followed him directly. I hurried after—knowing nothing else to do and nowhere else to go.

So we all came—not alone Lance and I, but all of us on the ship, the rest of them already gathered there, in that hall beneath the embroidered lion. My lady Dela was at the head of the table along with Griffin, and my place and Lance’s and Modred’s were vacant. We went to our places, Lance and I having to pass all that long distance down the table—and Modred took his after a moment, understanding that was what was wanted of him. Gawain was there, his hands clenched before him on the table, not looking up. Percy sat there equally pale, beside Lynette. And Vivien, whose bright eyes missed nothing.

“We’ll have an account, if you please,” Dela said, “Modred.”

“Lady, I think you’ll have had access by now to the tape I used. I’m sure Percy can understand it.”

“I don’t care to go through it all. I want to know why you did such a thing.”

Dela had not learned what had happened to us—my heart leapt and sank again in guilty relief—no one had told her about the stolen tape. I should, and had not the courage. And then I thought what that would do for Modred, how Dela would never trust him if she knew what he had heard. Or Lance. Or look at any of us the same.

And Modred as likely might tell her—having no nerves; and no knowledge of born-men.

“I explained,” Modred said, “that there was a chance of contacting it.”

“He—” I said aloud, my heart beating against my ribs, “Modred told me, lady Dela, that he had it figured—that if his plan failed, then—then there was Lynn’s, wasn’t there? But if Lynn’s failed—then—”

“How many of you consulted on this?” Dela asked sharply. “Gawain? Elaine?”

“I never—” I said. “I—”

But all of a sudden I was having trouble concentrating, because something had stopped, the noise forward stilled, and that diminished a great deal the noise that had been constant with us for days.

“I—” I tried to continue, thinking I ought, trying to gather a denial, to explain, but Griffin held up his hand for quiet.

“It’s stopped out there,” Griffin said.

“It’s—” Dela said.

And then that Sound was back again, our Beast talking to us over com. It had heard.None of us moved for the moment, and then Modred got out of his seat, and Griffin did, and the rest of us, as Modred headed out of the room.

We knew where he was going.

“Modred!” my lady cried.

But that did no good either.

XIV

... but she saw,

Wet with the mists and smitten by the lights,

The Dragon of the great Pendragonship

Blaze, making all the night a steam of fire.

And even then he turn’d; and more and more

The moony vapor rolling round the King,

Who seemed the phantom of a Giant in it,

Enwound him fold by fold and made him gray

And grayer, till himself became as mist

Before her, moving ghostlike to his doom.

Our Beast snarled at us, whispered to us, a low ticking that rose and assaulted our ears as we came—shaking us with the power of its voice. Vivien had come: she clung to the doorway with a kind of demented fixation on the sound. She had become entranced with her destruction, but that noise got to the bones and put shivers into the flesh, and Viv was right now close to sanity, in sheer fright. The crew headed for their places, but Lance laid hands on Modred to stop him.

“Let him go,” Griffin said, and Lance looked at Dela, and did what he was told. I stood by shivering, physically shivering in the horrid sound. But we were better than we had been, and braver: my lady stood there with her fingers clenched on the back of Modred’s chair and wanted answers from him—at once, now, immediately.

“We’re getting screen transmission,” Percy said, and it came up, a nonsense of dots and static breakup.

“That’s an answer,” Modred said calmly. He half turned, looking at my lady at his back, but receiving no instruction, he turned back again.

“What’s it saying?” Griffin asked.

Modred ignored the question, busy with a flood of beeps that came through, and Griffin allowed it, because Modred was doing something, and Percy was, and then Lynn and Wayne came over from their posts to watch. It was craziness; the bass clicking stopped and became a maddening loud series of pulses. I wrapped my arms about myself, standing there and not understanding any of it. Griffin and Dela didn’t understand: that also I came to believe. But they let the crew work with the computer.

“Equipment’s not compatible,” Modred said finally, the only word he gave us in all that time. “Stand by: we’re getting it worked through comp.”

“So it can hear us,” Dela murmured. She moved back, shaking her head, and Griffin put his arm about her shoulders.

Lance and I and Viv, we just stood there, not understanding anything—until of a sudden lines began to come across one of the screens and it began to build itself downward into a picture. I wasn’t sure I wanted to see—whatever it was. “We can clean that up,” Gawain said. The crew began to work, and Percy sweated over the computer in greatest concentration, while Modred intervened with small gestures, an indication of this and that, quiet words. And then Modred reached for another control. Lynn reached out instantly and checked his hand from that. “No,” Lynn said.

“My lady.” Modred half turned in his seat. “We have to transmit and give it something back to keep its interest. This is going to take us time.”

“Give it—what?” Griffin asked.

“The same thing as before,” Modred said. “Repeating it. Giving it the notion we’re still working.”

“All right,” Dela said quietly, and Lynette took her hand away, so whatever Modred wanted to send went out.

It went on a long while, this consultation, this meddling with the computer, and sometimes the lines on the screen grew clearer, and sometimes more confused. My knees ached, and my back and shoulders, so that finally I went over to that bench near the door where Vivien had sat down. After a moment more Lance came and took the place by me, silent company, image of other terrible nights trying to cope with this place.

But my heart was tired of beating overtime, and my limbs were all out of shivers. Terror had acquired a kind of mundanity, had become an atmosphere, a medium in which we just went on functioning, and did what we were supposed to do until somehow our Death would get to us. I reckoned that tired as I was it might not even hurt much. Maybe Vivien reckoned that way, sitting by me with her hands clasped in her lap—not blanked at all, but following this; and maybe Lance felt the same—who had Dela and Griffin in front of him, their arms about each other. Only the crew went on driving themselves because they had something left to do.

Our born-men—they had no least idea, I reckoned, what made sense to do, but they stood there, while the voice of our Beast rumbled away over the distant sound of hammering. At last Dela turned away as if she would leave—having had enough, I thought: this might wear on for hours. Almost I got to my feet, thinking she might need me—but no, she went only as far as the bench on the other side of the door, drawing Griffin with her, and they sat down there to wait it all out while the crew kept on at their work.

The image came clear finally, and it made no sense, being only dots. “Get the other one up,” Modred said, and they started it all over again.

So the crew kept at their work, still getting something, and whatever-it-was kept up its noise. And my lady, who once would have gone to her rooms and shut out the sound—stayed, not even nodding into sleep, but watching every move Modred made.

Not trusting him. Modred had said it. It was very clear why all of us were here, why this one night the lady stayed to witness, and therefore all the rest of us stayed. Modred had to know that.

There had been a time, when the Maidhad made tame voyages ferrying lovers from star to star, that my lady had liked Modred in contrast at her banquets, with his dark dour ways. He was the shadow in her fancy, the skeleton at the feast, the memento mori—a dangerous-looking sort whose impudence amused her, whose outrages she forgave. But that was before things had passed out of control, and we all had to rely on him. O my lady was afraid of him now, for all the wrong reasons—a grim face, an insolence which had taken matters into his own hands. And a name that had stopped being a joke. He was Modred: she had always had a place for him in her fancy. And so she stopped trusting him.

Me, with my little understanding—I watched him work, the fevered concentration, the sometime flagging of his strength, and the cold, cold patience of his face; and I heard his voice, always quiet, cutting through Percy’s dismay at something or Gawain’s and Lynn’s frustration—like ice it was, beyond disturbance ... and I knew what it was I feared. I was afraid of his reasoning.Modred dealt with our Beast because it was there to be dealt with like the chaos outside, like the numbers that came up on the machinery, a part of this universe and no more alien to his understanding than I was.

But Modred understood now he was not trusted, and he was threatened somehow by that. One little emotion had to be gnawing at him, who could feel nothing else. He had been jolted through a host of sensations in that tape, things his nerves had never felt before. It must have been like a dip in boiling water, leaving no clear impression what the water had been like because the heat was everything.

And what he wanted now, what drove him so, I had no least idea.

The work continued. As with our general terror, information wore us out and left us without reaction—one could only look at so many lines and dots and listen to so much talk that made no particular sense. I found my head nodding, and leaned on Lance, who was more comfortable than the wall; Lance leaned back then and his head bowed over against mine—I went plummeting down a long dark, just too tired to make sense of anything, and the voice of our Beast and the hammering at the hull sang me to sleep.

I came out of it aware of an ache in my neck and of a set of voices in hushed debate.

“No,” one said, and: “It’s been quiet all this time,” the other—Lynn and Modred. “No.” Percy’s voice. “There’s no way—” Gawain’s, rising above the level of the others. “Modred, no.”

“Lady Dela,” Modred said.

I waked thoroughly, sat up as Lance did, as all of us who had been drowsing came awake. Modred looked like death—no sleep, no food or drink but what I had brought him: it showed.

“Lady Dela, it’s answered. The transmissions—there’s an urgency—” He turned and started touching controls, bringing up a sequence of images, that was all dots and squiggles and lines and circles. “We’ve rationalized its number system, gotten its chemistry—it’s methane. There are all kinds of systems on the wheel—” He brought up another diagram, that was all a jumble of lines, and he pointed to it as my lady and Griffin got to their feet. “There, see—”

“I don’t make any sense of it,” Dela said.

“There.” Modred’s hand described a circle: I could see it among the lines when I looked for it, among the other shapes that radiated out from it. And then it made sense—the wheel and the ships appended to it, and the network of tubes that wove them all so that the whole looked like a crown seen from above, with rays and braidings going out in all directions. Modred’s thin finger lighted on a single point of this. “This is the Maid. Here. Oxygen.” His finger underlined a series of dots, and swept to another, impossibly complicated series of dots inside the wheel. “That’s methane out there. But here—” His finger swept the torus. “See, there’s oxygen, just beyond that partition out there; and a line going that way, from our bow, to that partition. We docked in the wrong segment, and they’ve corrected that. The torus—has seven divisions. Water, here: they must melt ice. And process other things. Here’s a different mix of oxygen; methane/ammonia and sulphur ...”

“You profess to read this thing’s language?”

“A dot code, lady.” Modred never looked back, went on showing us his construction—its construction, whosoever it might be. “It’s compartmented, various pressures, I’d guess, various temperatures for all its inhabitants. But these—” His hand went to the network of veins. “Methane. All methane. And we may be dealing with a time difference ... in thought. The creature talking to us sends the images very slowly. But put them together and they animate. Percy—”

Percy ran it back again to earlier images, and we watched, watched the torus naked of ships; and then ships arriving. We watched the network actually grow, watched the lines start from one ship and penetrate the torus, then penetrate the neighboring ship-figure. The dots in it—I had not noticed, but suddenly there were a lot of them.

“Do you see?” Modred asked. “The atmosphere in that ship went to methane. It changed.”

But now the lines were going in both directions. New masses popped up, more ships arriving; or asteroids and whole planetoids swept in, docked like ships, because some of the shapes were tiny and some were unaccountably lumpy. Some acquired lines crossing the torus to other sections. I watched, and I felt cold, so that when Lance put his arm about me, I was grateful. Maybe he was cold too. I reached out for Vivien, while the thing went on building, took her cold hand, but she simply stood there with her eyes fixed on the screen and no response at all to my touching her.

So the lines advanced, like blind worms, nodding about and leeching onto a ship-form or a bit of rock; and generally the ships went to that complicated pattern that meant methane. So Modred had said. He watched it grow and grow until the network was mostly about the torus. Until Modred pointed to a ship that suddenly appeared amid the net.