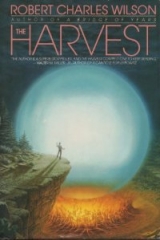

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Chapter 11

Kindle

The dream, in Tom Kindle s opinion, was just what it appeared to be: an invitation to submerge himself in a cozy, communal immortality. And while Kindle found the idea repulsive, he harbored no illusions about the attraction it would hold for his fellow men.

Therefore, in the two weeks and some days since that peculiar night, Kindle had stayed out of town. He wasn’t sure what Buchanan would look like when he saw it again. He wasn’t sure he wanted to know.

He had hoped to postpone any journey into town as long as possible, but that desire became academic when he slipped on a muddy hiking trail and came to rest twenty vertical feet down the west slope of Mt. Buchanan, his left leg broken at the hip.

* * *

Maybe he shouldn’t have been on the trail at all. Nothing had forced him out here. His cabin was well-stocked and he had plenty to read. Currently he was working his way through Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The book was not much more entertaining than yesterday’s dishwater, but Kindle had bought it as part of a five-foot shelf of the Classics of Western Literature, and he was determined to get his money’s worth.

Nor had claustrophobia driven him out. The cabin was spacious enough. He had bought this little property—some miles from Buchanan up an old logging road—in 1990. The cabin itself was a kit-built project he had put up with the help of a few friends, one a building contractor with access to quality tools. Since then, every penny that didn’t maintain his boat or buy food had gone into improving the property.

He paid for town water, since the municipality had run a public works line up here during the real-estate rush of the eighties. But his only electric power came from a gasoline generator in a shed out back. Winters were sometimes snowy, but Kindle had insulated the building and installed a woodstove to keep himself warm. No need for that this time of year, not just yet.

It was a cabin—not quite big enough to be called a house—but it was a comfortable cabin, and he wasn’t suffering from cabin fever. The impulse to take a long walk up these back trails had been only that, an impulse, obviously a stupid one. The dry spell had broken last week; rain had fallen for three consecutive days and the trails were wet. The trails were also, in places, steep.

And Kindle was, he hated to admit, not awfully young anymore. When asked, he gave his age as “about fifty.” In truth, he paid little attention to his age and disliked doing the calculation. When you live alone and work alone, who gives a doughnut hole about birthdays? Who counts ’em?

But he had turned fifty-three in January and wasn’t as agile as he used to be. Consequently, when he came up a muddy switchback where a fallen pine had carried off a square yard of the hiking trail, he wasn’t quick or canny enough to grab at the nearest root or sapling as his boots rolled under him and the world turned suddenly vertical.

He lost consciousness when the leg snapped.

* * *

When he woke again, some vital instinct kept him immobile. He did not dare to move, only blinked up at a sky crowded with moist conifers and worked at interpreting this sensation of something gone terribly wrong.

He was light-headed and not ashamed of talking to himself—not that he ever had been.

“You fell down.” The basic datum. “You slipped off the trail, you asshole.”

He swiveled his head and saw his own flight path traced in broken saplings and churned topsoil. Long way down. He had fetched up here: in a sort of gully in the hillside, his ass soaking in a cold stream and his legs curled at the trunk of a mossy old hemlock.

He took particular note of something he did not like at all: the way his left knee had rotated at such a peculiar crooked angle.

“Well, shit!” Kindle said. The sight of his broken leg made him feel both frightened and angry. Of the two, the anger was more vocal. He cursed eloquently and loudly, and when he was finished the forest fell silent—blushing, perhaps. And then there was the new and essential question that had to be faced, like it or not: “Tom Kindle, have you killed your idiotic self?”

Maybe he had. The cabin was a quarter-mile downslope—more like a mile by trail. Suppose he made it back: The cabin lacked a telephone. Help was in Buchanan, or anyway no nearer than the closest neighbor—another three miles downhill on a dirt and gravel road.

And there was no guarantee he could move even as far as the next sapling without passing out again.

He shifted his body experimentally and nearly did pass out. The pain when he moved was a brand-new thing, a burning stick thrust into his leg all the way up to. the small of his back. He let out a shriek that sent birds wheeling from a nearby tree. When he was still, the agony subsided but did not entirely retreat. It was concentrated in his left leg between hip and knee; everything below that was numb.

The leg needed a splint. It needed to be immobilized, or he simply could not move.

He raised his head and inspected the injury. There seemed to be no blood, no exposed bone; and that, at least, was good. Kindle had once worked at a logging camp in British Columbia, and he had seen a man suffer a leg injury that left his femur projecting from his thigh like six inches of bloody chalk.

The bad news was that this might not be a simple fracture; the knee might be involved. If Kindle recalled his first aid correctly, you don’t try to realign a joint injury. You immobilize it and “transport to medical care.”

He scanned the immediate area and located the burled walnut walking stick he always carried on these hikes. Good old stick. Friendly presence. Sturdy enough to splint a bad break. It’ll do, he thought. But it was about a foot and a half out of easy reach.

He pulled himself toward it, screaming.

He screamed throughout the process of binding his leg, an act that seemed to progress in waves. The waves were of pain, and when they crested—when he felt consciousness begin to slip away—he would lie still, panting and dazed, until his vision cleared; then he would work at the splint a while longer.

In the end, after a measureless time, the walnut walking stick was lashed around his thigh and lower leg with torn strips of his cotton shirt—a job he admired as if someone else had done it.

And if he moved?

The splint kept the leg more or less still and minimized the pain. Kindle dragged himself a short distance along the wet bed of the stream. The water was only a trickle, inches deep, but very cold. Not too bad on a warm afternoon like this… but it was late afternoon, and some of these end-of-summer nights got chilly when the sky was as clear and high as it was today. All this heat would leak away after the sun went down. And then he’d be wet and cold. “Hypothermia,” Kindle said out loud. Not to mention shock. Maybe he was in shock already. He was shivering and he was sweating, both at once.

He inched downhill along the bed of the stream. The stream crossed a trail some yards down. Then he could get out of the water. But not until then. There was no way he could drag his fiery, useless leg through the undergrowth of this dense Pacific Coast forest.

It occurred to him as he crawled along the rocky creek bed that if he had accepted the offer of the aliens he might not be in this position. He would be immortal. There would be a Place Prepared For Him, as Kindle’s mother used to say. His mother had been religious. Dakota Baptist. Cold winter Baptist. Her philosophy went something like: Kick me till I go to heaven. Kindle’s natural father had died of a heart attack while he was driving a snow plow for the municipality; two years later his mother married a carpet installer who got drunk every Saturday night. Oscar was his name. On the coldest Saturday night of a cold Dakota winter, Oscar had been seen, and become famous for, pissing out the second-story bedroom window while singing the Hank Williams tune “I Heard That Lonesome Whistle Blow.” Which was all well and good, and nothing Kindle would hold against a man, but Oscar was also a mean and petty drunk who used his fists more than once on Kindle’s mother. It was all right, she said, marriage was always a rough road and anyhow there was a Place Prepared For Her. Kindle, who was fifteen, put up with six months of this before he decided that if there was a place prepared for him, it was somewhere outside the city limits. He rode to New York City on a Greyhound bus, lied about his age, and served an apprenticeship as a merchant seaman. Five years later he took a trip back home. Oscar was unemployed, drinking Tokay on the steps of the Armory, not worth beating up even for the cold comfort of revenge. His mother had left long since. No forwarding address, which was probably a smart move on her part.

Thus Kindle was alone and suspected there was no Place Prepared For Him, a suspicion the following thirty-three years had done nothing to dispel. He did not believe in heaven, and he had turned it down when it was offered. Now, however, he wondered if he’d been too hasty.

A Place Prepared might be better than this damp forest, which was getting darker, now that he noticed.

The sky had turned a deep and luminous blue. Had the sun set? Yes, it had, but only just. These old firs and hemlocks were heavy with shadow.

And he was on the trail now, inching along the dirt, caked with mud. When had that happened?

And his throat was raw with screaming, though he did not remember screaming. He wasn’t screaming now. The sound he was making was more like a moan. It was a kind of song, not entirely tuneless. It reminded him of the song the flying monkeys sang in the movie The Wizard of Oz.

This thought made Kindle feel almost jaunty. He looked up at the stars—now there were stars—and wondered if he could sing a real song. Somewhere under all this pain, he had developed a conviction that everything was actually very funny. This was a funny position to be in. Singing would make it even funnier.

The trouble was, he didn’t know very many songs. Oscar’s bedroom aria aside, he had never paid attention to songs. He had learned “Jesus Loves Me” at the Baptist Sunday School, but he was damned if he’d sing a Sunday School song when there wasn’t even a Place Prepared For Him. He knew “The Streets of Laredo,” but only one verse. Maybe one verse was enough.

“As I went out walking the streets of Laredo—”

Mind you, he shouldn’t have gone out walking.

“As I went out walking in Laredo one day—”

No longer day, but night.

“I met a young cowboy all dressed in white linen—”

He began to wonder if he liked the direction this song had taken.

“All dressed in white linen and cold as the clay.”

No, it was the wrong song entirely.

But he went on singing it, and his sense of giddy detachment failed him, and he grew miserable with the thought that, he couldn’t even decide for himself what song he ought to sing.

* * *

He came within sight of his cabin as the Artifact rose in the western sky. A kind of moon, it cast a little light. That helped. But the sight of it was a fearful thing for Kindle.

He couldn’t say he hated the Artifact. It hadn’t given him any cause for hatred. But he had always been suspicious of it. Well, so had everyone else; but Kindle’s suspicions had been broader than most. Most people suspected it was an alien spaceship come to wage war or blow up the earth or some such thing. Kindle had doubted that. His experience of the passage of time was that the thing that happened was never the thing you expected. Whatever came of this Artifact, Kindle had thought, it would not be the monster-movie scenario everyone feared. It would be something, certainly not better, but surely different—new, unexpected.

And hadn’t events proved him right? No one had expected this visitation in the dark, this whisper in the ear about Life Eternal.

Certainly Kindle had never guessed that tiny machines in his nervous tissue would ask him whether he wanted to give up his body and certain habits of mind and grow beyond Kindle into something that was both Kindle and much more than Kindle.

His answer had been immediate. No, by God. He had clung to his aging body and intemperate ego all these years and he wasn’t eager to give them up. He disliked the idea of his soul mingling with other souls. He was alone by choice and by nature, and he wanted to keep it that way.

But he wanted to live, too. It was not a love of dying that made him turn down the offer. He wanted desperately to survive. But on his own terms.

He wanted to live, and that was why he was here, prostrate at the door of his thirteen-year-old Ford pickup truck, singing “The Streets of Laredo” in a faint raw voice and wondering how to endure the thing he must do next.

* * *

To enter a vehicle one must stand up.

Even a one-legged man can stand, Kindle thought.

Unless his pain prevents him.

Unless the act of pulling himself up by the door handle of an old pickup truck grinds bone against ragged bone and causes him to stop singing and makes him scream again instead.

Unless he passes out.

But Kindle remained conscious even as the landscape performed a pirouette around the fiery axis of his spine.

His useless leg, bound and curled at the knee like the leg of a dead fly, flopped against the door of the truck.

Key! Kindle shrieked to himself.

He carried his keys with him always. He braced himself with his right hand and fished in his pocket with his left. Maybe it was stupid to lock up his truck when he lived this far from people. Who would come out here to steal such a wreck? But it was his habit to lock up the things he owned: his truck, his boat, his cabin.

He found the key, transferred it to his right hand, somehow fumbled it into the lock without moving the rest of his body.

Then he took a deep breath, slid away from the door and opened it a crack.

Good work.

But his left leg was splinted, and he dared not tamper with the splint—so how was he supposed to cram himself behind the wheel? Once behind the wheel—what then?

He took the key from the door and clasped it tight in his right hand. “Tom,” he said in a hoarse whisper, “this is the hard part. That other part was easy. This is the hard part.”

Easier still to lie down and go to sleep. Drive in the morning. Or die before dawn.

More likely that second possibility, Kindle thought. Dying would be the easiest thing of all. Maybe he could even drag himself to the cabin and die on his own sofa, which would at least lend some dignity to the event. People would find him after a while. Maybe they would find his worm-track leading down from the mountain. Goddamn, they would say, look at what this man did! What an admirable man whose corpse is lying on this sofa!

Was this his sofa? Nope, Kindle realized: This was the front seat of the old Ford pickup, and he was stretched out across the length of it.

* * *

These memory lapses were disturbing, but he imagined he could hear the echo of his own screams fading down the hillside. So perhaps it was better not to dwell on the past.

He pulled himself into a sitting position with his back against the driver’s-side door and both legs stretched out across the seat. He could see over the dash well enough. But there was no way to get a foot down to the floor pedals.

At least he was out of the wind. That was no mean accomplishment. He looked around for a way to push the pedals. His resources were meager. Within reach: an empty styrofoam cup, a snow brush, and a copy of Guns and Ammo. Not too helpful.

Oh, and one other thing. The walking stick he had used to splint his leg. The leg had swollen enormously. From crotch to knee, it looked like a cased sausage. The rags he had used to bind the splint were deeply embedded, the knots pulled tight by the pressure.

Don’t make me do this, Kindle thought. No, this is too much. I can’t even begin to do this.

But his traitorous hands were already fumbling against the feverish flesh down there.

* * *

When he came to himself again, he found the walking stick clutched in his trembling left hand.

It was still nighttime, though the Artifact had set. Maybe it was coming on toward morning. Kindle didn’t know; he didn’t wear a watch. The stars looked like morning stars.

He was shaking like a sick animal. This shaking was a bad thing, it seemed to him. Made it hard to keep the broad end of his walking stick secure against the floor pedals. And it would only get harder when the truck was moving.

He put the key into the ignition, pumped the gas pedal twice and turned the key.

The engine coughed but didn’t catch.

That was normal. Kindle sometimes thought of this old Ford as his “hiccup truck” for the way its engine fought him. It would catch, run, stall; or nearly stall, misfire, rattle and bounce for a time before it settled down. “Come on, you sack of shit,” Kindle whispered. “Come on, you lazy turd.”

The engine caught and lurched and Kindle screamed as the truck jogged on its ancient shocks. His broken leg was braced against the seat, but there was nothing to hold it and no way to prevent it flopping around in that sickening, loose way.

Kindle tried to sing “The Streets of Laredo” as he put the truck into gear and pressed the gas—a terrible stagger forward—and steered out of this dirt turnoff away from the cabin toward the logging road.

He switched on the lights. The pines crowding the roadside loomed in eerie grids of shadow.

He was sitting sideways and a little low. He wasn’t accustomed to steering with his left hand and his reflexes were shot, but he managed to aim the Ford approximately midway down this column of spooky-looking trees. God help anybody coming uphill, but who would be, at this hour?

From here into the outskirts of Buchanan was mainly a downhill ride, and Kindle found he didn’t have to work the gas pedal much; it was struggle enough to keep the walking stick pressed against the brake to impede the acceleration of the truck. It occurred to him he’d be in some profound trouble if he passed out again. “So stay awake,” he told himself. He remembered that a Place Had Been Prepared For Him in the regional hospital as long as he didn’t run his hiccup truck off the Streets of Laredo.

He passed two other cabins—the property of men as solitary as himself—but he didn’t stop. If he stopped, nobody might be home; and Kindle did not relish the prospect of starting up this truck again. Better to drive as far as possible toward Buchanan, or at least down to where the streetlights began.

But then—in a wash of fear that took him by surprise—Kindle remembered that Buchanan might not be the Buchanan he remembered.

Last week, the monsters had come to Buchanan.

Curious ambulatory sponge-things who had infected everybody’s blood.

Was this a real memory or some kind of trauma hallucination? Well, Kindle thought, it sure felt like a real memory.

Still: Monsters?

And if that was true…

He did not summon the images, but here they came: Monsters out of comic books, tentacle-headed things unloading from a flying saucer; or the zombie-eyed human eunuchs out of a dozen movies, slaves of the Overmasters and hungry for human flesh. They had Prepared a Place For Him on the communal barbecue.

Kindle shook his head. He couldn’t decide whether this was funny or scary. Maybe it would be smart just to press on the brakes and die in the dark up this mountain.

(He did, in fact, apply a sudden pressure there, because the truck had picked up a great deal of speed without his noticing.)

No, Kindle told himself sternly. No dying allowed. Go for help. Follow the plan.

See the monsters if you must.

The truck rattled on.

* * *

He had reached the suburban margin of the town just inside the city-limits sign when his pain and fatigue crested, and the truck rolled into an embankment and came to rest with its headlights pointed at Orion.

The impact dashed Kindle against the steering wheel, causing the horn to emit a squawk; then he rolled back, semiconscious, into the seat. The truck’s motor rumbled on.

The sound of the horn and the grinding engine woke a thirty-year-old insurance investigator named Buddy Winkler, who had recently become immortal but who still liked to get a good night’s sleep. He went to the window of his two-year-old tract house and gazed with sleepy astonishment at the semivertical Ford riding a dirt bank in the vacant lot next door. Then he phoned 911. He gathered up a blanket and hurried out to the accident, where he quickly surmised there was nothing he could do to help the injured man inside—a screaming and broken mortal man whose eyes rolled wildly at the sight of him.

Monsters, Kindle thought—dimly, when he thought at all.

Monsters leering down at him.

He screamed until he was mute.

* * *

And after a dark time he recognized hospital corridors, and understood for one lucid moment that he was lying on a gurney cart with medical staff bustling around him.

A frowning face lofted into proximity, and Kindle reached up with what remained of his strength and took this person by the collar of his gown.

“Get me,” Kindle gasped, “a human doctor.”

“Relax,” the entity pronounced. “I am human.”

“You know what I mean, you alien shitsack! Get me a human doctor, you monster!”

Kindle fell back gasping.

The man looming over him turned away. “Can we have some sedation here? The patient’s hysterical. Oh, and somebody call Matt Wheeler.”

Now I think maybe I am safe, Kindle thought, and embarked upon a sleep that would last for two days running.

* * *

Giddy light-headedness and fog. Kindle awoke once again.

He was in bed. His leg was bound and in traction. It hurt, but only a little. Kindle guessed he was sedated and that right now nothing would hurt very much.

He felt distant and vague, and he supposed if you tore off his arm and beat him with it that would be okay, too. Probably a nice opiate drip on that IV.

But the main thing was that he had made it to the hospital. He took a certain pride in that. His memory was fuzzy, but he recalled that it had been a long and harrowing journey.

A man in medical whites approached. Kindle watched this process with languorous detachment. He managed, “You must be the doctor.”

“That’s right, Mr. Kindle.”

“I asked for a human being.”

“You got one. My name is Matt Wheeler.”

Matthew Wheeler was an ordinary-looking man with a woebegone face. He’s too young, Kindle thought idly, for all those frown lines. “You’re human, Dr. Wheeler?”

“As human as you are, Mr. Kindle.”

“Not one of them?”

“No. But they can treat you as well as I can. There’s no need to worry.”

“Maybe,” Kindle said. “Has the town changed much? I’ve been up in the hills since, since—” Since what was it called? Contact.

“Not much.” Dr. Wheeler looked uncomfortable. “Not yet.”

“How’s my leg?”

“It should mend reasonably well. In time. May I ask how you broke it?”

“Walking out back of my cabin. Fell in the fuckin’ mud.”

“How did you get into town?”

“Dragged my ass down to my truck.” The memory was a little clearer now. “Then I drove.” He shrugged.

“That’s remarkable. That’s quite an accomplishment.”

Kindle was alert enough to recognize a compliment. “I guess I’m hard to kill, huh?”

“I guess you are. You were a sorry mess when the ambulance brought you in, or so I’m told. The leg will heal, Mr. Kindle, but you’re going to be here for a while.” The doctor made a notation on his clipboard. “I understand your attitude about… human beings. But I can’t be in the room twenty-four hours a day. You’ll have to cooperate with the hospital staff. Will you do that for me?”

“You’ll be around, though?”

“I’ll be around. I’ll make a point of it.”

Kindle nodded agreement.

“You’ll probably want some more sleep.” The doctor turned to leave the room.

Kindle closed his eyes, then opened them. “Dr. Wheeler?”

“Yes, Mr. Kindle?”

“How many of us are there? I mean—there are more of us in town, aren’t there?”

The doctor looked even wearier. “A few. I want to get us all together in a couple of weeks. Kind of a town meeting. Maybe you can be there. If you lie still and let that bone mend.”

Kindle nodded, but vaguely; he had already forgotten the question, was already easing back into sleep.