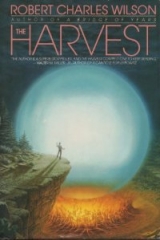

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Part Two

One in Ten Thousand

Chapter 8

Buchanan Awake

Simon Ackroyd, D.D., Rector of St. James Episcopal Church since his appointment to Buchanan in 1987, woke from a long sleep thinking about the Aztecs.

By the end of the fifteenth century, the Aztec Empire had brought the practice of ritual sacrifice to such a pinnacle of efficiency that on one occasion in 1487 eighty thousand individuals—prisoners of war—were systematically killed, their beating hearts extracted with obsidian knives. The lines of victims stretched for miles. They had been caged, fattened, and sedated with a plant drug called toloatzin so they would endure the nightmare without struggling.

The Aztecs, when Simon read about them in college, had been the first real test of his faith. He had grown up with what he recognized now as a sanitized Christianity, a pastel Sunday School faith in which a gentle Jesus had redeemed humanity from the adoration of similarly pastel pagan idols—Athena and Dionysus worshiped in a glade. The problem of evil, in this diorama, was small and abstract.

There was the Holocaust, of course, but Simon had been able to rationalize that as a terrible aberration, the horrendous face of a world in which Christ commanded but did not compel.

The Aztecs, however… the Aztecs had lodged in his mind like a burning cinder.

He could not dispel the persistent, horrible vision of those lines of prisoners snaking through angular stone colonnades to the temple at Tenochtitlan. It suggested whole worlds of unredeemed history: centuries fathomless, Christless, and unimaginably cruel. He envisioned the sacrificial victims and thought: These were men. These were human beings. These were their lives, alien and terrible and brief.

And then, one night in Episcopal Seminary, he had dreamed himself talking with an Aztec priest—a bony, nut-brown man in a feathered headdress, who had misunderstood his horror as religious awe and who responded with his own attempt at a compliment. Our knives are trivial, the priest had said. See what your people have achieved. All your missile silos, your invisible bombers, each one an obsidian knife aimed at the hearts of tens of millions of men and women and children; each one a temple, painstaking, ingenious, the work of an army of engineers, contractors, politicians, taxpayers. We have nothing to compare, the Aztec priest had said.

And Simon had awakened with the chilly suspicion that his own life, his own culture, everything familiar and dear, might in its essence be as twisted and cruel as the stone altars and kaleidoscopic deities of the Aztecs.

His faith sustained him through college, through his divinity degree, through his appointment to this parish. He was a thoughtful Christian, and on his good days he suspected his doubts only made him stronger. Other times—when the winter fogs enclosed Buchanan, or on moonless summer nights when the pines seemed to take on the barbed and thorny aspect of Tlaloc, the Aztec god of the underworld, in the repulsive mural of Tepantitla—he wished his doubts could be abolished, annihilated in a light of faith so intense it would wash away all these shadows.

Then—last night—he had had a very different dream.

* * *

He woke tentatively, as if exploring a world made new and unpredictable. Which perhaps it was.

Simon felt the world wake up around him. It was waking, he knew, from a very dramatic and peculiar kind of sleep.

But the immediate world, his world, was still the same: same bed, same bedroom, same creaking wooden floors.

The fair weather had not broken. Simon opened the bedroom drapes. The rectory was a wood-frame house erected in the boom years after the Second World War, next door to the church, in the old part of Buchanan riding up the foothills from the bay. A modest house: its luxury was this view. The morning sky was luminous above blue ocean water. Wind stirred up foam on the crests of the waves.

The world was transformed but not new, Simon thought. Or rather, it was the human landscape that had been transformed. They are at work inside us now.

He shaved and wondered at his reflection in the bathroom mirror. Here was a gaunt forty-five-year-old man, receding hair and graying beard, quite ordinary, but all of us, he thought, have become remarkable underneath. He dressed and padded downstairs in his bare feet. It was Simon’s special indulgence to go barefoot around the house on pleasant summer mornings. His housekeeper, Mary Park, disapproved. She would glare at his feet as if they were a display of obstinence or bad taste, then shake her head. In fact, Simon rather admired his feet. His feet were unpretentious, unadorned, unbeautiful. They appealed to his Protestant impulses. They were “plain” feet, as the Amish might say.

Mrs. Park knocked and entered as Simon was tuning his small television set in the parlor—actually the church’s television set, usually appropriated by the Sunday School for audiovisual displays. The rectory had been connected to cable last June at Simon’s expense and for the purpose of indulging his addiction to news broadcasts and PBS. He tuned in CNN this morning, where a dazed female announcer was describing the events of the last thirty-two hours in baffled generalities. Apparently Western Europe was still asleep. Simon had a momentary vision of the Earth as an animal, a bear perhaps, groggy after a winter’s hibernation, stumbling toward the light.

Mrs. Park offered a distracted “Good morning.” She ignored his bare feet for once and began to assemble his breakfast—two eggs, bacon, and buttered toast. It was a cholesterol sin he could never bring himself to renounce. In any case, he was hungry this morning: He had slept for a night, a day, and another night. He thought with some awe of the morning he had missed, of the silent afternoon no human being had seen.

Mrs. Park seemed to be keeping an eye on the television through the kitchen doorway. Simon turned up the volume for her.

“Evidence of this ‘enforced sleep’ is inescapable,” the newswoman was saying. “Reports of injuries, remarkably, are nil. Reports of the subjective experience suggest a direct, almost telepathic, contact with the orbiting Artifact.”

And so on. Simon wondered how long this pretense at objectivity would be maintained. Good grief, he thought, we know all this.

No one wanted to name what was looming in the future. Elysium, he thought. Jerusalem. The illud tempus.

He adjourned to the kitchen when Mrs. Park summoned him. Had breakfast ever smelled this good before? Or was his body already different in some way?

She hovered at his shoulder. “Dr. Ackroyd—”

“Yes, Mary?”

“You had the dream?”

“We all did.”

His housekeeper confessed: “I told them—I told them yes.”

“Yes, Mary. So did I.”

She was obviously surprised. “But you were religious!”

“Why, Mary, I still am. I think I still am.”

“But then how could you answer them yes? If it’s all right to ask, I mean.”

He considered the question. Not a simple one. Many of his deepest beliefs had been challenged in the last thirty-odd hours. Some had been abrogated. Had he been tempted? Had he yielded to temptation?

He pictured the temple at Tenochtitlan, the arc and fall of the obsidian knives.

“Because of the Aztecs,” he said. “Sir?”

“Because there won’t be any Aztecs in the world anymore,” the Rector said. “That’s all finished now.”

* * *

The question had been posed in democratic fashion and it was becoming obvious that the yeas outnumbered the nays.

Mary Park had said yes, and so had her husband Ira; and they had known this about each other as soon as they woke and exchanged glances across the bedsheets. Ira was sixty this year, seven years older than Mary. All spring and all summer his emphysema had kept him housebound and weak as a child—his day a slow rotation of morning game shows, afternoon movies, evenings rereading the sports magazines that came in the mail. This morning he sat up and took a deep, experimental breath… then coughed, but not as deeply or painfully as the morning before. The air felt good. Sweet summer morning air, fresher than hospital oxygen. It was like a memory long forgotten and suddenly recalled. Do you want to live? Yes, by God! This morning he wanted very much to live. Even if it meant—in the long run—a certain strangeness.

Lingering in bed, Ira Park thought briefly about the possibility of going back to work at Harvest Hardware, where he had labored behind the counter for twenty-five years. Then he figured not. He had spent twenty-five years in retail sales and that was enough for one lifetime. Find something new to do for the next twenty-five years. Or twenty-five hundred.

* * *

He had been replaced at Harvest by Ted Keening, eighteen, who had been described by his high-school guidance counselor (in a private joke in the teachers’ lounge) as “not exactly college material. Too dumb for an academic scholarship, too fat for a sports scholarship, and too poor to buy his way in.”

Ted was a television junkie and still some twenty pounds bigger than he’d like, but he’d lost weight since he started working at the store. There was a fair amount of physical labor involved, hauling stock up from the basement and so forth. But Ted was beginning to realize that his future contained more than a career in measuring chain and weighing nails. He had awakened this morning with the knowledge that he didn’t have to die and that pretty soon no one would be liable to call him fat or stupid—which was how he had thought of himself even before he paused by the east window of the teacher’s lounge and overheard his guidance counselor’s joke. His reaction to this morning’s revelation wasn’t triumphant or gloating, just… he guessed “astonished” might be the best word. He didn’t completely understand what was happening. It was too big to understand. But he felt the future. His own. The world’s. The future had become a curious and wonderful thing. It shimmered on the horizon like a heat mirage, as hard to see, as achingly bright, but much more real.

* * *

He told his boss he might not be working at Harvest much longer. Mr. Webster, who had also said yes to an unvoiced question during his long sleep, told him he understood and that, as far as he could tell, there might not be hardware stores much longer. Which would be kind of a shame, given the years and money he had invested in this place. “But what the hell. I’m sixty-five years old. I’d have to give up the store one way or another. I guess I’d sooner walk away from it than get shut in a coffin. Ted, I think we’re all bound for something we can’t even guess at. It’s as strange a thing as I have encountered, and you probably feel the same. But unless you’re done with us already, would you mind ringing up these items for Mr. Porter?”

* * *

Billy Porter, Beth’s father, was a fairly steady customer. Usually he came in for car parts from the automotive section. Billy was always fiddling with his ten-year-old Subaru, a car that stalled at intersections no matter what he did to the choke or the idle or any other part he could get his hands on. Or he came in to buy shells for his hunting rifle, Billy being an occasional hunter whenever his friends offered to drive him up into the mountains. Today he had bellied up to the checkout with a selection of garden tools, which Mr. Webster found vaguely amusing: The idea of Billy down on his hands and knees in the mulch… planting tulips, maybe…

But maybe it wasn’t so funny. “Becky always kept the garden in such fine shape,” Billy said. “I’m ashamed how I let it go. I thought it wouldn’t take much cleaning up. A little work, what the hell.”

“Taking the day off?” Mr. Webster asked.

“Taking an easy shift, anyhow. I don’t know how much longer they’ll need me down at the mill.” Billy had also said yes.

* * *

Some few had not.

Billy’s daughter Beth had answered No!—had understood the offer and rejected it. She couldn’t say exactly why. Something in her had grown sullen and hard and had drawn away from this alien touch. No, not me. You won’t steal from me my dying.

But she woke knowing what she had turned down and it made her a little sad. The real question was, What next? What threats and possibilities lurked in this soon-to-be-new world?

She hiked down to the mall and called Joey Commoner from a pay phone.

Joey didn’t want to talk about it, but Beth understood from his cryptic responses to her careful questions that Joey had also said No.

Wouldn’t you know it? Birds of a feather, thought Beth. Well, damn. The last real people.

The last Aztecs, Rector Ackroyd might have said.

* * *

There were others.

Miriam Flett, who woke that morning with her agonies and virtues intact, but with a new idea of whose Hand had touched her during the night.

Tom Kindle, who had lived on the slopes of Mt. Buchanan for five years in a cabin without city electricity. He came into town summer weekends, when he operated a private ferry to the bay islands, but he spent his winters alone and liked it that way. What he didn’t like was the shape of the miracle he had been offered in the night. A lemming future, Kindle thought. No damn privacy.

One junior member of the City Council and one city clerk. A salesman at Highway Five Buick.

Matt Wheeler.

Chapter 9

Many Mansions

When he woke, Mart’s first observation was that his fever had broken. He felt clearheaded and alert—there was nothing left of the sedation of the night before. But something was wrong.

He rolled over and reached for Annie, but his hand touched empty sheets.

Like everyone else, he had spent the night dreaming. His dream had seemed vividly real… was real, some part of him insisted. But Matt was equally determined that it must not be real, and he screwed down that determination like a carpenter’s clamp over all errant and contrary thoughts. A dream, he instructed himself, was only a dream.

The house smelled of frying bacon and buttered toast. Matt dressed in weekend clothes, Levi’s and a sweatshirt, and headed for the kitchen. A bar of sunlight crossed the tiled mosaic floor. A window stood open and morning air plucked at the curtains.

Annie and Rachel were collaborating on breakfast. Matt stood in the doorway a moment before they noticed him. They were giggling at some joke, heads together, Rachel in shorts and an old khaki shirt, Annie still in her nightgown. They cracked eggs into a blue plastic bowl.

It was Annie who turned and saw him. Her smile didn’t fade, exactly. But there was a hitch in it—a blink of uncertainty.

“Breakfast coming up,” she said. “For late risers. Jim and Lillian left early, by the way. They said thanks for the party and they’d stop for food at McDonald’s.”

“Wasn’t much of a party,” Matt said.

“Some wine, some friends. What else do you need?” Annie shooed him toward the table. “Go on, Matt, sit down. If you try to help you’ll just get in the way.”

He watched her move around the kitchen, tousle-haired and pretty in her nightgown. They hadn’t made love last night. Blame it on the Taiwan Flu. But it had been much, much too long since the last time. Matt recalled five separate occasions when he had considered asking Annie to marry him, and each time he had shied away from the question, diverted by some lingering guilt or just a fear of disturbing the status quo, their fragile dalliance. Should have asked her, he thought. We’d have had more of these mornings. More nights in bed.

Rachel was curiously cheerful serving up the scrambled eggs. It was a rare pleasure to see her smiling. When she was a toddler, that grin had been big and infectious. Celeste would take her shopping and strangers would offer compliments—“Such a happy baby.” She’d been a happy baby, happy toddler, happy little girl. It had taken Celeste’s death to erase that smile, and Matt was surprised at the depth of his own reaction now that he was seeing it again. How long since she’d smiled like that? Not a brave smile or a halfhearted smile but a big Rachel grin?

But this was a thought both maudlin and dangerous, and Matt suppressed it and focused his eyes willfully on the varnished tabletop.

Rachel joined him at the table; Annie did not. He said, “You’re not eating?”

“I ate. I have to dress. You two take your time.”

She left the room, but not before Matt noticed a glance that traveled between Annie and Rachel like a semaphore signal.

He looked at his watch and saw that the date crept ahead an extra day. How had that happened? In his dream he had seemed to sleep much too long—but that was only a dream. Focus, Matt thought. He suffered a momentary fear that the world might fade around him, the walls of reality shatter to reveal… a void.

“Want to hear the radio?” Rachel asked.

Christ, no, Matt thought. “No—please.” He was afraid, for reasons he could not admit, of what the radio might say. She recoiled a little. “Sorry, Daddy.”

“It’s all right.”

She picked at her eggs. The silence in the room was suddenly weighty, and Rachel’s smile had faded.

“Daddy,” she said, “I’m okay. Really.”

“Of course you are.”

“You’re worried about me. But I’m fine. I really am. Daddy?” She looked at him intently. “Daddy, did you dream last night?”

He would not endure the weight of the question. He fought a childish urge to close his eyes and cover his ears. He looked away from Rachel and said, through a wave of shame that seemed to thicken his tongue, “No, honey, I didn’t. I didn’t dream at all.”

* * *

He drove Annie home along the bay shore.

Buchanan was quiet again today, but it was a normal Saturday quiet, not yesterday’s odd and uneasy tranquility Folks were out in the morning cool, mowing lawns, weeding, making grocery runs. Matt allowed himself a moment’s appreciation of all this suburban peace.

A blue haze rode up the slope of the mountain. The air through the wing window carried a rich bouquet of pine resin and sun-warmed asphalt. Matt followed the lazy curve of the road past the commercial dock, where a trawler stood in rust-colored repose, through the business district and beyond a high bluff of land to the apartment complex where Annie lived.

He had never understood why she chose to live in this down-at-the-heels corner of town, in an old walk-up building with pasteboard walls. She had never explained. There were a lot of things Annie had never explained. Where she disappeared to the second Saturday of every month, for instance; or why she had never replaced her genteel but ancient furniture.

But she invited him up, and he accepted the invitation. For all its apparent poverty, this was still very much an Annie kind of place: a bedroom and a big living room overlooking the bay, sparsely furnished, clean wooden floors, the elderly tabby-cat Beulah snoozing in a patch of sunlight. The apartment was as economical as a haiku: Every detail mattered.

Annie spooned out coffee into the basket of her coffee maker. Beulah had been fed by a neighbor; she paid no attention to the kitchen noises. The machine began to burble. Annie said, “We have to talk, Matt.”

He knew that “we have to talk” was polite code for an impending emotional meltdown, and he didn’t like it. He stood at the window and watched the ocean roll out blue and calm to the horizon. Did they have to talk? Was silence such a bad thing?

“Matt?” she said. “Did you dream last night?”

It was almost possible to hate her for the question.

He said, “Rachel asked me the same thing.”

“Oh? What did you tell her?”

“I told her no.”

“I don’t think she believed you.”

“She didn’t say.”

“J don’t believe you.”

He turned away with enormous reluctance from his view of the sunlit sea. “What’s this about, Annie?”

“I had a dream,” she said. “Rachel had a dream. I think every living human being on the surface of the Earth had that dream. Even you.”

He fought an urge to bolt for the door. He was sweating, he was tense, and he couldn’t resist his own diagnosis: Denial, announced the premed hotshot inside him. You’re denying what you don’t want to face.

He sat down at Annie’s lacquered pine dinner table and closed his eyes. Beulah bumped against his leg. He picked her up. Beulah began to purr.

“All right,” he said flatly. “Tell me what you dreamed.”

* * *

But it wasn’t a dream, Annie said, not really. It was a visitation, and the agency of that visitation had been the microorganisms—or machines—Jim Bix had warned him about.

(“No, Matt, don’t ask me how I know these things. I just do. Let me finish.”)

The microbes were neither organism nor mechanism, Annie said; they were an amalgam of both, or something beyond either. They were capable of reproduction and were even, in their own dim way, intelligent. They had been distributed into the atmosphere by the trillions upon trillions, had ridden the jet stream to the extremities of the Earth, and by the end of July they had colonized every human organism on the surface of the planet. Within the last week they had begun to reproduce; their growth and their activity was what had produced the alarming hematology results.

Their job was to function as the voice of the Artifact. That is, of the Travellers.

Annie called them “Travellers” because that was their name for themselves: It defined them. Like the microbes they created, they were not organic beings. Unlike their creations, they once had been. They had been both organic and planetbound: creatures like ambulatory sponges, building their cities in the methane-rich tidal sinks of an Earth-sized moon orbiting a Jovian planet of an unimaginably distant star.

They had outgrown their world. They had poisoned it with organic and machine wastes, a catastrophe averted only by their abandonment of both organism and mechanism. In the wake of that crisis they became Travellers: planetless, bodiless.

The Artifact was their world now. It was both a physical structure and a much larger virtual environment. They inhabited it, a greater number of souls than the Earth contained human beings, but only a few of them occupied physical bodies at any given time, and then only for the purpose of repairing and maintaining the Artifact itself.

They were, she told Matt, not a hive or a computer or any such easily imagined thing; they were separate creatures, individuals, unique—but capable of so much more, being immaterial; of complex joinings and indefinite sleeps, of enduring the long journeys between stars without boredom or decline, of learning without ending. Their lifespan was indefinite, unlimited. They had achieved a kind of immortality.

They had been Travellers, Annie said–knowing some of these things only as she said them—since the Earth was a whirl of dust and the sun a hot new star, and they had forgotten nothing of what they had seen in those millennia. They were a vast library of inconceivably ancient wisdom, and they had arrived at the Earth at what they considered a critical and fortuitous moment, because, Annie said, we are what they had once been: intelligent, planetbound, and poisoning a world with our waste products.

It was obvious, she said, why they hadn’t communicated with governments or world leaders. They had a better means of communication, the cybernetic microbes, a kind of arm of themselves with which they could touch each human being individually. This more intimate contact was the only communication worthy of the word. The microbes, which might be called neocytes, interfaced with nervous tissue, touching but not changing it. At the brink of Contact they had soothed the frightened population of the Earth—sedated us, Annie said, yes, but only long enough and deeply enough to prevent panic. Then they had induced a kind of long, deep sleep, and in that sleep the Travellers had spoken. They had spoken to six billion human beings over the course of the next thirty hours, and what they spoke was not merely language but a complex of, for lack of a better word, understandings, deeper and more profound than language could ever be. And they had explained all this and more, much more than Annie could tell.

But Matt, she said, you must have felt it: All the possibilities… the literally infinite possibilities… the lives they led… and their place, the Artifact, like a nautilus shell, not dead, as it had seemed, but filled with lives strange and various beyond belief. They must have showed you that.

They must have offered it to you, Annie said. Because they offered it to me.

They said I could have it, too.

Do you want to live? they had asked. Live without dying? Live, in effect, forever?

And Annie had said yes.

Do you want to live, they had asked, even if you change? Even if you become, in time, something no longer entirely human?

And that had given her pause; but she thought again of their long, complex, interesting lives; she understood that everything changed, that death itself was a kind of change, that of course it was impossible to live forever without changing—change was to be expected.

And again she said yes.

* * *

She poured coffee and put the cup in front of Matt. Matt examined the cup. It was a solid thing, gratifyingly real. A familiar thing.

Beulah yawned and jumped out of his lap; preferred, apparently, the sunlit floor.

Annie put her hand on his shoulder. “What did you tell them, Matt?” He pulled away from her touch. “I told them no.”