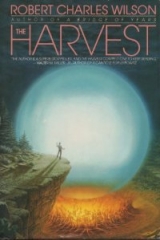

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Tyler never actually met this man, who preferred to remain safely distant; he was a retired lawyer, Tyler understood, who paid his way into a military boarding school of some repute. The boy was bright; everyone admitted that. Sullen sometimes. Given to fantasy. A loner. But smart as a whip.

He enlisted in the Army with good prospects, earned his lieutenant’s bars, earned a bachelor’s degree at the government’s expense, faced a bright future as a commissioned officer.

He did carry a few black marks on his record. During basic infantry training, he had come close to killing another man, a memory that still troubled him. It was an impulse. There was no other word to describe it. One moment he was practicing a takedown; the next he was strangling the man. It was nobody in particular. It happened to be a stringbean named Delgado, who was actually a friend of his, more or less. But that didn’t matter. What mattered was the sudden and overwhelming need to do harm, to carve his name on a stranger’s life as painfully as strangers had carved their names on his. Plus it gave him an erection.

Three other men had dragged him off Delgado, who gagged and vomited. No permanent damage had been done, however, and in view of Tyler’s otherwise excellent record, the event was written off as an anomaly. It was a pattern he would come to recognize. The phrase in light of this soldiers otherwise commendable performance decorated a whole drawer of complaints. Not insubordination—never that. Drunkenness, fistfights, slovenly dress, once a speed run through Saigon with the military police behind him. But only at certain intervals, certain dark passages in his life, certain times when he heard Sissy’s voice too often in his head—that is, only during his madnesses.

It had slowed his rise from the ranks. When you reach a certain point, Tyler discovered, your private life begins to matter. You start being seen at parties with embassy personnel, in a decorative role, offering dances to the wives of ambassadors and the daughters of diplomats; consorting with people who want you to be their little brother in uniform, an American Centurion with a cute little pixie wife and maybe a freckled three-year-old in military housing somewhere. They didn’t want you trafficking, for instance, with Asian prostitutes, unless you were very discreet, and they didn’t look kindly on the rumor that you’d been seen in a different red-light district altogether, where the traffic leaned toward young Asian boys.

It was only that his passions inclined to youth, a certain androgynous beauty he craved but couldn’t define. He came to the Asian boys, Asian girls, telling himself it was simply a need to be satisfied, and he left hating them for their grace, their wantonness, their doe-eyed acquiescence.

He learned discretion. Discretion served him well for some years. Discretion did not fail him until his posting to West Germany, where his military career came to an end. He had found a whorehouse in Stuttgart, in a pretty little building next to a pretty little beer garden in a part of the city not much frequented by Americans; and he had selected a Turkish immigrant girl who claimed to be thirteen years old and by her looks might not have been lying; and he had been upstairs with her, the girl naked and mumbling “Bitte, bitte,” through a mouth filled with the Colonel’s erect penis, while he held his service revolver to her head and stroked its trigger, gently, not even near the point of firing the weapon—when the house matron came through the door screaming at him.

Apparently it was her custom to keep an eye on her employees through a number of peepholes in the old plaster walls, and she had seen Tyler put his revolver to the girl’s head—but it was really only a kind of play; was that so hard to understand?—and believed he was about to commit a murder.

Tyler was startled by the woman, and when he turned the revolver did go off—he shot the girl through her skinny left arm. It was a mistake.

An ambulance came, the police came, he was arrested. He was held for questioning by a red-faced man who told him, “This is not the Wild West! This is not where you shoot and fuck!”

He was never charged. But he was held for three days, and the incident was reported to his superiors; there was an investigation, some local scandal-mongering. People began to look at him differently. That was the hard part. People knew. They looked at him… well, the way people used to look at Sissy.

He resigned his commission. He had made enough friends to ease the transition into civilian life, but it was a difficult time. The Stuttgart incident seemed to be always at his heels, seemed to follow him like some odorous lost dog.

It fades, Sissy said. Memory fades. Everyone forgets everything. That’s the rule.

But the nights were long. Some nights were too long, and on those nights he would drive his second car, an anonymous brown sedan, along dark city streets where the girls were usually black or Hispanic and very young, to cheap hotel rooms that stank of insecticide and perspiration, where he would sometimes, even after Stuttgart, play the Gun Game with them.

And in the aftermath, home before dawn, alone, he might toy with his service revolver, pick it up, put it down, put it to his temple, the touch of the steel a familiar sensation after all these years, the oily smell of it a comforting smell. Sissy always talked him out of pulling the trigger. The Sissy in his head. Sad ghost. Don’t kill yourself and be like me.

And in time his daylight life grew bearable. He was trustworthy, he was discreet—he had learned all about discretion—and he was smart. He moved between the military, the defense contractors, and the congressional committees with a growing familiarity. His job was to say plainly what his employers could only hint at, and to hint at what his employers would publicly deny.

And his madnesses came and ebbed in their own slow, tidal rhythm; never predictable and impossible to resist. And the years passed.

Meeting A.W. Murdoch and wearing himself out on the firing range had postponed the madness for now. But it would come again, Tyler knew. It always came. And came again.

* * *

When he had learned the basics of the TOW, he drove with Murdoch to an empty stretch of U.S. 95 and parked in the breakdown lane under a stand of shade trees.

Yesterday Murdoch had roamed up and down this pike in a commandeered sports car making notes on the position of the Helpers. A stream of the devices had been flowing through Baltimore on 95 for some weeks now, always travelling at a steady forty miles per hour and at regular intervals. Some turned west on 70 or installed themselves in road towns like Columbia or Wheaton ; most continued south on 95. One had taken up a position on the White House lawn.

Tyler himself hadn’t seen one with his own eyes, only the TV pictures. It was worse close up, Murdoch told him. “They aren’t just black, like painted black or anodized black. They don’t shine in the sunlight at all. They’re blacker than their own shadows. And when they move, Colonel, they don’t tremble or bounce. They glide. You ever play a computer game, sir? You know how things move on a video screen? Like math. Like oiled perfection. That’s how these things move.” The idea of trying to stop one, Murdoch confessed, as much as it appealed to him, it also… well, it scared him a little.

“You can deal with it, though?”

“Oh, hell, yes. Sir, I’m anxious to deal with it.”

So here they were, parked on a sunny stretch of road at the edge of a cow pasture where a few Holsteins grazed, or perhaps they were Guernseys, Tyler got those confused; a dairy breed, in any case. Crickets sang in the high grass and faint clouds dappled the horizon. The air was cool. November was only a day away.

“Any old minute now, sir,” said Murdoch, who had calculated this somehow.

Tyler focused his attention on the highway where it crossed a low ridge a couple of thousand yards north. The Helper would be coming over that ridge. Well within range. But nothing moved there now, not even traffic. The roads were sparsely travelled these days.

Murdoch popped a can of Dr. Pepper, which made Tyler jump. “Christ’s sake.”

“Sorry, sir.”

Tyler’s mouth was dry. He envied Murdoch that can of pop fresh from the cooler. But he had to be ready to man the TOW. He guessed this was Murdoch’s revenge for not being allowed first shot at a Helper. Tough luck, Tyler thought. I guess I can wait for a cold drink.

“Sir? I think you have a target, sir.”

Tyler stood up on the shooting platform and manned the weapon.

The TOW was manufactured by Hughes, a company Tyler had done some business with. He had a lot of respect for the TOW. It was a wire-guided weapon, almost mind-numbingly complex, but reliable in service. It was designed to penetrate heavy armor plate and render even the best-protected tank functionally unserviceable, i.e., blow it the hell up.

He got his first good look at a Helper through the cross hairs of the 13x optical sight.

The Helper looked like a death-black ball and cone—the aliens seemed to love these Euclidian shapes—and it was travelling well below the speed limit along the slow curve of the road. The image rippled slightly in the heat rising from the asphalt.

The cattle shuffled and raised their heads as if they sensed this presence.

Tyler was suddenly nervous—suddenly this seemed like real combat—but he didn’t let the anxiety affect his timing. He kept the Helper in his sights until it cleared the high spot in the road. He wanted this target clean.

“Sir,” Murdoch said nervously. “We’re a little exposed here.”

“Keep your shirt on, Mr. Murdoch.”

A long pause, then: “Sir?”

Tyler triggered the weapon.

The TOW performed a number of complex tasks between one eyeblink and the next. Tyler’s finger on the firing button ignited a rocket motor, which popped the missile from its launch container. All the rocket fuel was used up before the missile left the tube, which was what protected Tyler, Murdoch, and the vehicle they were sitting in from the backwash. The sound of the launch was blisteringly loud. It was a sound Murdoch had compared to the hiss of Satan’s own steam press.

When the missile was well clear, a sustainer motor ignited; the missile unfolded four wings and accelerated to 900 feet per second.

Tyler’s eyes were on the Helper.

The TOW missile trailed two fine wires attached to the launcher. Tyler actually used the sight and a joystick to drive the missile, which never failed to astonish him, this video-game aspect of it. He steered the missile down a trajectory that seemed eternally long, but was not. He kept the cross hairs centered on the moving Helper. Picture-book launch.

The missile arrived in the vicinity of its target travelling at 200-plus miles per hour.

The warhead was fitted with a standoff probe that exploded fifteen inches from the target.

The main warhead detonated a fraction of a second later. Hell of an explosion, Tyler thought, his ears ringing. “Holy damn!” Murdoch whooped. The cows and crickets had fallen silent.

* * *

Tyler had once seen a movie called War of the Worlds, loosely based on the H. G. Wells novel.

Martians land in California and build monstrous killing machines.

Conventional weapons fail. At last, the Air Force drops a nuclear device.

Explosion. Mushroom cloud. Nervous observers wait for visibility to improve. The firestorm abates, the dust settles… The Martian machine is still there.

Tyler leaned against the hot mass of the TOW launcher, scrutinizing the spot on the highway where the missile had detonated.

The smoke swirled up and away in a lazy easterly breeze… And nothing at all was left behind.

* * *

Murdoch couldn’t resist driving to the spot, though Tyler’s instinct was to get away as quickly as possible.

He stopped and idled a few feet from the scorch marks.

Nothing remained of the Helper but a fine, sooty-black dust—a thick arc of it clean across the highway.

“Nice shot,” Murdoch said.

“Thank you.”

“Spose you’re right, though, Colonel. Spose we ought to scoot.”

“Commence scooting,” Tyler said.

It was a small beginning. But it was also, Tyler thought, the first human victory after a long humiliation. He closed his eyes as Murdoch raced the Hummer into the cool October air. It had been a genuinely lovely autumn, Tyler thought. A beautiful fall.

After a time, the crickets started up again.

Chapter 17

Two Eagles

Northwest autumn weather moved in from the ocean on the third of October and settled over coastal Oregon like a contented guest. The sky darkened, the rain came in mists and drizzles, dusk began at lunch and lingered till dinnertime.

Matt was afraid this would go on through the winter, that they wouldn’t see the sun again until April. He was happy to be proved wrong. Five days before Halloween, the clouds parted. One last bubble of warm air, drawn across the Pacific from Hawaii, paused above Buchanan. The dew dried on the pine needles and the grass wondered whether it ought to start growing again.

Over breakfast, Matt recalled what Cindy Rhee had told him.

Talk to your daughter.

The child was right, of course.

He had barely spoken to Rachel since Contact. He’d been busy—spending time at the hospital, trying to keep the ER functional, then organizing the Committee.

But even when he was alone with her in the long evenings, too silent, when the sun declined and the Artifact cast its bony light, or the rain talked to the roof… still, he couldn’t bring himself to speak.

Not to say the important things.

He was too much aware of the change in her, of the neocytes, so-called, at work inside her skull.

Changing her. Carrying her away.

To speak of it would be to invite the grief, which he could not allow, because there had been too much grief in his life already. He couldn’t afford more grief. He was tired of grief.

* * *

But maybe the time had come.

He found her sitting at the kitchen table eating a bowl of cereal and reading a library book. The book was propped against the cornflake box and braced with her left hand. It was Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, and it seemed to Matt she was turning the pages a trifle too quickly. Better not to dwell on that. Her hair was uncombed and she was wearing a blue nightgown. She looked at him as he entered the kitchen, a look both hopeful and wary.

He moved to the counter and started measuring out coffee. His hands were hardly shaking at all. “Busy today, Rache?”

“No,” she said.

“Feel like a drive? I thought maybe we could ride out to Old Quarry Park. Last nice day of the year, maybe.”

“We haven’t been up there for a long time,” Rachel said. “In the mood for it?” She nodded.

* * *

Rachel understood that her father wanted to talk, wanted to make sense of what had happened; and she knew how hard it was for him. She wanted to help but didn’t know how.

He drove the long way up toward Old Quarry Park. As the road rose along the flank of Mt. Buchanan, she could see the town sparkling in its bay, polished bright as a jewel by all that rain. There was no plume of smoke from the Dunsmuir pulp and paper mill down south. There’d been no smoke from the mill for a couple of weeks now.

The car turned down a side road past the reservoir, and Rachel realized where this detour was taking them: “The Old House!”

Her father nodded.

They always called it the Old House. It was the house where Daddy had grown up. Back in the old days, before her mother died, they would go on this drive every once in a while… maybe twice a year, when Daddy was in the mood. They would drive past the Old House, and Daddy would talk about what Buchanan had been like long ago; and Rachel would picture him as a child, as strange as that seemed, her father as a ten-year-old in jeans and a grubby T-shirt, trekking through the power company clearcuts on his way to school, or carrying peanut butter sandwiches out to the bluffs on warm Saturdays like this.

The street where he had grown up was called Floral Drive, a grand name for ten 1950s box houses on a cul-de-sac with backyard views of the distant bay. Rachel recognized the Old House at once as Daddy slowed the car. There was nothing special about it. It had a shake roof and aluminum siding painted brown. The number 612 was marked on a gatepost with ornate brass numerals. Daddy didn’t know who lived here now. Strangers. He hadn’t lived in the house himself for more than twenty years.

There was no traffic; he stopped the car and let it idle.

“My grandfather died here,” he said. He was looking at the house, not at Rachel. “I was ten. He lived with us for the last three weeks of his life. He died of a bone cancer just before Christmas. But he loved to talk, and he was fairly lucid those last three weeks. I sat in the bedroom with him so he’d have somebody to talk to. He was born one year before the century turned, if you can imagine such a thing. He was twenty during the labor troubles in 1919. He talked about that a lot. Seattle was the big IWW capital of the Northwest, but there was a lot of labor trouble in Buchanan, too. Buchanan was a logging town back then. Some bars, a hotel, City Hall, the harbor, loggers in on weekends to drink and carry on. The Wobblies were organizing at the Dunsmuir mill. In 1919 they called the big general strike up in Seattle. Buchanan had its own sympathy strike. Just like Seattle, the strike was put down with clubs and cops. Your great-grandfather—this was Willy, on the Hurst side of the family—he worked at Dunsmuir. He was part of the labor parade. Two hundred men marched into the City Hall Turnaround with red banners. The mayor in those days was Bill Gunderson, he was in the pocket of the Dunsmuir family—he called out a bunch of Army regulars and they advanced with fixed bayonets. Three people were killed before the fight was over. Everybody went home bloody. Willy said the big fight was over the IWW banner. Everybody was yelling, ‘Protect the flag!’ Two guys got hurt, one blinded, the banner went down, but Willy and another man grabbed it and carried it up the hill behind City Hall and planted it in the Civic Gardens—it stood there ten minutes before the troops fought through the crowd and pulled it down.”

He turned to face Rachel. “That was his victory. That bloody flag. Ten minutes. He wanted me to know that before he died. He wanted me to know he wasn’t just an old man sick in bed. He was Willy Hurst, and he had saved the flag from the soldiers.”

“You never told me that before,” Rachel said.

“It was the first time I really understood this town had a history… that people had histories. A town is a living thing, Rachel. It has memories.”

“Yes,” she said.

“I can’t walk away from it. Not without trying to save it.” She nodded unhappily. “I know.”

“That’s how it is for me.” He shifted gears and drove away from the Old House, back toward the road, toward Old Quarry Park. The morning sunlight was hot through the car windows. “Now you,” he said. “I want to know how it is for you.”

* * *

Old Quarry Park was a wooded ridge running from the northern slope of Mt. Buchanan to the sea, a mile southwest of the abandoned mineral quarry that had given it its name. Hiking trails wound through the tall coastal firs, but the center of the park had been developed in the 1970s: There was a bandstand, a Little League diamond, a playground. Rachel had been taken to play here on summer weekends since she was three years old.

On one of those long-ago summer Saturdays, she had fallen and cut her forehead on the rim of the whirl-around. Matt had cleaned and bandaged the cut. She remembered his hands, huge and warm. Doctor hands. Their confident touch.

These memories had been coming back to her lately. It was part of the change.

He walked beside her from the parking lot through the trees to the picnic grounds. He was superimposed on her memory of him, an older version of himself. It seemed as if he had aged years in the last few weeks.

They sat at a wooden table at the western end of the picnic grounds where they could see through the trees to the ocean. The sun was bright and high. A couple of jays made a quarrelsome sound overhead, but the bees, a summer peril, had deserted the park altogether.

I want to know how it is for you. She was a dutiful daughter and she meant to give him an answer. But it wasn’t easy.

There was so much to say.

“Daddy, you know what Contact was like. You must remember, even if you said no. That feeling of doors opening up… of a promise of something wonderful. Of being something that doesn’t live and die but goes on, changing all the time but not stopping.”

“I remember,” he said. His face was drawn, expressionless, pale in the sunlight. “That didn’t frighten you?”

“Not when I understood what it meant. It was hard at first being so… transparent. They talk to you, but they’re talking to the inside of you. Your, I guess, soul. And your soul talks back. That’s scary. You can’t hold anything back, you can’t hide anything. But then you understand they’re not sitting in judgment, it’s not St. Peter at the Pearly Gates. They’re not even offering forgiveness, that’s not their business—their business is understanding. And then you start to realize how big they are. Big with all the growing and learning they’ve done over the centuries. Like some kind of beautiful seashell that gets more complicated and more colorful the longer you look at it, every chamber with a smaller chamber on one side and a bigger chamber on the other, all echoes and alabaster.…”

Her eyes were closed, and she realized she’d drifted into rhapsody. This Contact memory was strong. But she wasn’t accustomed to talking about it and she was probably scaring her father.

She glanced at him. His lips were drawn tight.

“I couldn’t say no,” she finished, inadequately.

“Even though it means giving up so much?”

“Giving what up?”

“Life. A normal life. A family. The way human beings have lived since they came out of the trees.”

“But I haven’t given that up. People used to say, is there marriage in heaven? Well, this isn’t exactly heaven. But I think there will still be marriage. People are people, Daddy. They’re each unique, they want different things from each other. They find partners. They fall in love. Maybe they don’t get married at the First Baptist anymore. But we’re not turning into loveless monsters.”

“It’s hard for me to know that.”

Rachel said, “I don’t know how to convince you.”

“What troubles me is that there’s a mechanism that’s altering your brain. Physically changing it. Rachel, that’s where love is. Loyalty, trust—even the way we perceive the truth. I tell myself this is all voluntary, you’re not being deceived. But I’ve seen surgeons produce bliss with an electrode in the cerebral cortex.”

“Have I changed?”

“Yes. You don’t talk the same way. Aren’t you aware of it?”

“I know about that. But me. Everything that makes me Rachel. Has that changed?”

He was silent for a long time. Finally he looked away from her, and the pain in his eyes was nearly unbearable. “I don’t know, Rache. I honestly don’t know.”

She felt herself on the verge of tears. She didn’t want to be understood.

She wanted to be held. She wanted him to wrap his arms around her, tell her it was okay, tell her he still loved her.

Voice trembling, indignant, she could only manage: “I’m not different.”

Not inside, she meant. Not where it counted.

* * *

On the day Rachel turned four years old, Matt had caught her drawing on the living room wall with her birthday crayons—big lime-green loops and whorls. The wall had been painted two weeks previously, and it must have looked to Rachel like a big blank sheet of paper.

Matt had paid for the painting the same week the car insurance came up for renewal. The household budget had bottomed out; Celeste was cooking Kraft Dinner instead of steak. Rachel’s tricycle, which she had ignored since this morning, had pushed their VISA card to the credit limit.

He went a little crazy when he saw the wall.

He grabbed the crayon out of her clenched fist and pushed her back. “Bad,” he said, “bad, Rachel, bad, bad!”

Her legs went out from under her. She sat down hard and her face clouded instantly.

Almost as immediately, Mart’s remorse began to flush away the anger. Rachel stammered through tears: “I’m… not… bad!”

He thought it was a cogent moral point. He also thought he wanted to shoot himself.

He picked up his daughter and held her. “You’re right, Rachel. You’re not bad. But it was a bad thing to do. Even good people do bad things sometimes. That’s what I meant to say. It’s a bad thing to draw on the wall. But you’re not bad.”

It was the way she phrased her objection in Old Quarry Park that convinced Matt he still had a daughter—at least for the time being.

I’m NOT different.

He felt those old father tears well up.

“Ah, Rache,” he said. “This is all… so confusing.”

She came around the picnic table to him. He stood up and barked his knee on the pineboard tabletop. It was an awkward ballet, but the hug went on a long time.

* * *

After a while, she went to a swing and asked him to push. A little bit of old times, Matt supposed. Maybe it was good for her to be ten years old for a few minutes. Maybe it was good for him.

He pushed her, she laughed, the sky was blue.

After that they walked the short trail that looped into the forest, but the track was muddy after all the rain. When they emerged into the sunlight, Rachel said, “We should have packed a lunch.”

“I have a better idea. Lunch at Dos Aguilas.”

“Really?”

“My treat.” He added, “If it’s open.”

“I think it is,” Rachel said… and he wondered how she knew.

* * *

Dos Aguilas was a Mexican restaurant at the bayshore. Matt recalled that Celeste had once classified it as a “linen-tablecloth” restaurant, as opposed to the plastic-booth kind at the malls. It had a cook, not a controlled-portion dispensing machine.

Arturo, the manager, had inherited the business from his father. The restaurant itself had been here since 1963. A landmark. It was still open for business. Empty, but open.

Arturo welcomed them in, and Matt nodded to him, but he understood by the glance that passed between Arturo and Rachel that they were of the same tribe now; Matt was the outsider here.

He chose a table by the window where they could watch the sunlit water lap the pier.

“It means Two Eagles,’” Matt said.

Rachel opened a menu over her cutlery. “What?”

“Dos Aguilas. It means Two Eagles.’ The story is that a pair of harbor eagles have a nest near here. You can have dinner some nights and maybe see them circling over the crab boats, diving for fish.”

“Really?” She gazed out across the water. “Did you ever see them?”

“Nope. Don’t know anybody who ever did. The story’s almost half a century old. But people still look.”

Rachel nodded, smiling at the thought.

Arturo came to the table. He took their order and headed for the kitchen, disappearing into a foliage of decor: sombreros, pistol belts, pottery. Matt said to his daughter, “You knew the restaurant would be open.” She nodded.

“You know things. Not just you. Other people, too.” He told her about the figure Tom Kindle had been quoting, one in ten thousand. “Rachel, how would anyone know that?”

She looked thoughtful. “It’s approximately the right number.”

“Okay. But how do you know?”

“Oh, I just… shift gears.” Tm sorry?”

“Well, that’s what I call it. It has to do with making connections.” A pause. “Daddy, do you want all the details of this?”

“Yes.”

“Because it’s strange.”

“I kind of took that for granted, Rache.”

She gave him a look: Well, okay… if you insist.

“It has to do with the neocytes,” she said. “One of the things they are is a kind of connector. You can think of them as drawing invisible lines—between people, between people and the Artifact.”

“Like telepathy?”

“In a way. But I think that gives the wrong impression. The lines they’re drawing are knowledge lines. The Travellers think there should be as few barriers to knowledge as possible. People’s lives are private, if they want them to be, but knowledge—knowledge is infinitely sharable.”

“What kind of knowledge?”

“More or less any kind.”

“Give me an example.”

“Well… suppose I want to know how to get from here to Chicago. Used to be I’d have to look at a map. Now I can just remember it.”

“Rachel, you’ve never been there.”

“No, but I’m not remembering it from myself, I’m remembering it from somebody else. Anyone who’s ever looked at a road map. It isn’t my knowledge, but I can get to it if I need it.”

“That’s all there is to it? Remembering?”

“That’s hardly all there is to it, but that’s what it feels like. I suppose it’s more like data sharing or something computery like that. But it feels like remembering. You have to actually do it, I mean there’s a mental effort involved—like thinking really hard. Shifting gears. But then you just… remember.”

“What if it’s something complicated? Quantum theory, say. Neurosurgery.”

She frowned, and Matt wondered if she was shifting gears right now, as they spoke.

“You can do that,” she said, “but it has to be orderly. In the Traveller world, knowledge is infinitely available but functionally hierarchic. You have to take the logical steps. What’s the good of knowing, for instance, that you can derive classical probability from the squared modulus of the quantum complex amplitude, if you don’t know what a modulus is, in physical terms, or an amplitude? The knowledge is available, but if you want to understand it you still have to eat it one bite at a time. Like this salad. Thank you, Arturo.”

“My pleasure. Get you something to drink?”

“A Coke,” Rachel said.

“For you, sir?”

“Anything.” His mouth was dry.

* * *

Rachel said, “I didn’t mean to be scary.”

“No. You took me by surprise, that’s all.”

“I surprise myself sometimes.”

The meal passed in awkward silence. Matt noticed Rachel glancing off across the water—checking for eagles. Once you started, it was hard to stop. “You still look sad,” she said when Arturo had brought his coffee. “Do I?”

“You were happy for a little while. Because we talked. But only for a while. Because of what’s happening.”