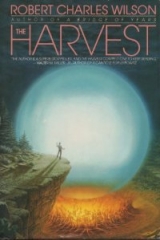

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“You don’t want that?”

She shook her head fiercely. “I’m not ready for that. Christ, no. It’s hard even being around him since he changed. He even looks different now. You remember how big he used to be? Now he’s almost skinny. None of his clothes fit. He looks—” She chose a word. “Empty.”

She used the nail of her right index finger to draw an oval in the fog on the passenger window. She gave it eyes, eyelashes, a pursed mouth. A self-portrait, Matt thought. “So I’m staying at the Crown Motel. The one by the waterfront, past the ferry dock.”

Matt turned right at the next intersection, toward a blankness of fog and rain, the ocean. “You could have done better than a motel. Look at Tom Kindle.”

“The room is big enough. It has a kitchenette, so I can cook. I get along.”

The rain turned icy again, clattering against the roof of the car. Matt eased past the sign that said CROWN MOTOR INN, the car fishtailing on a slick of ice. He realized he hadn’t seen a single other vehicle during this drive from Tom Kindle’s house–no traffic of any kind.

A light was burning in Beth’s room. She left it on, she said, so she could find the door at night. “It gets lonely in this big parking lot.” She cocked her head at him. “You want to see the place?”

“The roads aren’t getting any better, Beth.”

“You could walk me to the door, at least.”

He agreed… though it seemed somehow careless to leave the dry enclosure of the car.

Beth had appropriated a ground-floor room. The number on the door was 112. The door wasn’t locked. It opened into yellow light. “Just take a look,” Beth said. “Tell me it’s a nice place. God, it would be nice to have somebody tell me that.”

He stepped inside. The room was hot; the thermostat was turned up. She had decorated this ordinary suite with cheap art prints—pastel water-colors, kittens and farmhouses. A quilt, obviously homemade, had been thrown across the bed. She followed his look. “It’s the only thing I took with me when I left home. I slept under this quilt since I was little. My grandmother made it.” She sat on the bed and stroked the quilt with one hand. “Do I have to call you Dr. Wheeler? Everybody at the party called you Matt.”

“You can call me Matt.”

“Matt… you can stay here tonight if you want.”

Some part of him had expected the offer. Some part of him was surprised, even shocked.

“Because of the weather,” Beth said. “The weather being so shitty and all.” She began unbuttoning her shirt. “I hardly see Joey anymore. He just plays with that fucking radio over at Kindle’s. It wouldn’t be so bad—I mean, Joey’s hardly a prize—but he was the only person who ever… I mean, he used to say I was pretty.” She paused to gauge his reaction. “Nobody else ever said that.”

She slid out of the shirt. Her skin was perfect, blemishless, flushed pink. Her breasts were small, the nipples almost childlike. There was a line of freckles across her breastbone. Why couldn’t he say anything? He felt as if his mouth had been disconnected from his body. He was mute.

WORTHLESS, said the small blue letters on her shoulder.

“I’m twenty years old,” Beth said. “I guess you’ve seen me naked since I was ten. You never said if you thought I was pretty. I guess doctors don’t say things like that. Matt. Matthew. Matt—do you think I’m pretty?”

“Beth, I can’t stay here.”

She unzipped her jeans and stepped out of them, then sat back on the bed. She frowned. Then she folded her hands in her lap in a gesture that was oddly shy. “I don’t know why I do this shit.” She looked imploringly at him. “It’s hard being alone all the time. The town is empty. It’s not just that no one comes out on the street—I think people are actually missing. And I don’t know what happened to them. And I lie here and I think about that and it’s just so fucking scary. Sad and scary. And I would like not to be alone. But you can’t stay?”

“I’m sorry.”

“Is it as easy as that?”

“It’s not easy.”

It wasn’t. She was twenty years younger than Matt… but he wasn’t old, and she wasn’t a child, and the sight of her was deeply arousing. He hadn’t shared his bed with anyone since that August night with Annie Gates. And Beth was right about the town, Matt thought: It was empty, and it was scary, and the touch of another human being would be a powerful magic on a bitter winter night.

But she was vulnerable and too needy, and it was an act that might have unforeseen consequences.

She managed a small, embarrassed smile. “Telling the truth?” She looked him over, perhaps noticed the obvious bulge in his blue jeans. “I guess you’re telling the truth. You want to stay but you think if you stay it might be… dangerous? Can I use that word?”

He managed a nod.

“Hey,” she said. “I’m dangerous.” She stretched out across the bed in a motion that was both sensual and weary. “Maybe I had too much to drink.…”

“Maybe we all did.”

“Or maybe I’m a round-heeled little cunt. As my daddy used to say.”

* * *

He drove home on ice, through ice, a night all ice and darkness.

The house was dark when he arrived. The baseboard heaters stuttered and creaked. Rachel wasn’t home.

He hoped she was sleeping in a warm place this Christmas Eve.

But it wasn’t Christmas Eve anymore, Matt realized; it had been December 25 since midnight, since before he left the party. It was Christmas morning.

* * *

By Christmas noon, most of the ice had melted from the streets. Matt drove to the City Hall Turnaround and confronted the Helper a second time.

He wore his winter coat and a scarf Celeste had knitted for him in a time so remote it seemed like prehistory. Blades of grass, stiff with frost, crackled under his feet.

He stood close to the Helper—close enough to touch it. Rachel had said the thing could speak; but where was its mouth? Could it see him? Did it have eyes? Did it know he was here?

He supposed it did.

He began by cursing it. He called it a fucking intruder, a monster, a stony heartless motherfucking monument to all the needless cruelty that had been visited on the Earth.

He had to restrain himself from striking it, because he sensed its invulnerability, knew how easy it would be to beat his hands bloody on that unyielding surface.

He cursed it until there was nothing left in him but speechless hatred.

The silence, after that, was almost shocking.

He waited until his voice came back—he had worn it raw.

“Tell me,” he whispered. “Tell me what you know. Tell me what we have to do to survive.”

He took a quick step backward—surprised in spite of himself—when the Helper opened its eyes, or what seemed to be eyes, twin patches of sleeker blackness on the black orb of its head, weirdly mobile, like two slick dots of oil.

And it spoke—a voice deeply resonant, somehow artificial, completely terrifying.

“This is not a safe place any longer,” it said.

Chapter 21

Skin

It was good, at first, cruising through these southern towns, drowsy little November towns in Virginia, North Carolina, parts of Kentucky and Tennessee.

The towns were much alike. Each had its church, its central school, its highway mall—and each town had its Helper, nested at the center of it like a worm burrowed into an apple.

John Tyler personally destroyed several of these devices, and his friend A.W. Murdoch dispatched more. Murdoch was a surer hand at the TOW, much as Tyler disliked to admit it. We each have our talents, he told himself, and Murdoch was an excellent shooter.

At first they took elaborate precautions. Tyler thought the M998 was too obvious a vehicle; to conceal it, they navigated the highways in a stolen eighteen-wheel A P truck with the Hummer and its TOW platform parked in the rear.

Murdoch argued that this was a simpleminded piece of sleight-of-hand, not likely to fool anyone. The Artifact was probably as effective a surveillance tool as the average military satellite, and the Contactees were an unlimited source of information on the ground. “Sir,” Murdoch said, “if they want to get us, face it, they can get us—we’re mostly counting on their pacifism.”

Tyler yielded to the argument. After a week or so they abandoned the container truck and simply drove the Hummer from place to place, along highways and secondary roads that were generally empty, following a route Tyler hoped would seem random but that tended to the south. Tyler had not been warned about the weather, but he had already noticed an odd restlessness of wind and rain; he thought they’d be safer wintering below the snowbelt.

All this, plus his friendship with Murdoch, served to keep despair comfortably distant. At least for a time.

* * *

Tyler’s first warning that things had changed came in a little Georgia town called Loftus.

They had driven through dozens of towns like it. These little towns seemed emptier as the days passed, Tyler thought. One seldom saw the populace; either they had gone elsewhere or were locked indoors. Only a few lights came on at night. It was disturbing. It was even, if you let yourself dwell on it, frightening; but at the same time it made travelling easier. They spent nights in deserted motels; they drove freely in the daylight.

They arrived in Loftus at noon. These buildings, the three-story hotel and restaurant, the barber shop bedecked with Wildroot Cream Oil stickers, had probably not changed in any important way since the Korean War. There was a Helper, of course. It stood on a traffic island where the highway passed between a hardware store and a yellow-brick Kresge’s. Murdoch fired the TOW and Tyler watched what he had come to think of as the customary fireworks: an explosion that shattered windows on all sides and left the road littered with glass and black dust.

Murdoch drove on through Loftus in moody silence. Murdoch had been moody since they left D.C., but hadn’t wanted to talk about it. Tyler mentioned that they would need to locate another source of missiles before too long: the munitions they had carried from Virginia were about to run out.

“If there’s any point to it,” Murdoch said. “We’re pissing in the ocean, if you ask me.”

Tyler gave him a hard look. Murdoch’s uniform was ragged, oil-spotted, and torn from working on the Hummer. He wore a jacket he had stolen from a retail shop in an empty mall. His hair was long and matted.

“There’s more of these Helpers than we can ever hope to shoot,” Murdoch added, “and I don’t see any evidence we’re doing any real harm—and shit, Colonel, maybe that’s as it should be.”

“I don’t understand,” Tyler said.

“Don’t you? Are you sure? After Contact, I figured everybody was turned into zombies, it was like a horror movie, Invasion of the Body Snatchers.… I just wanted to kick some ass. Show somebody the human race wasn’t that easy to knock over. You know what I mean?”

“Certainly.”

“But it isn’t like that. Fuck, I knew all along it wasn’t like that.” Murdoch kept one hand on the wheel and used the other to unscrew the lid from the coffee thermos. “Didn’t want to admit it.” He took a long swallow. “But maybe they aren’t getting such a bad shake—all those zombies. Life eternal. Not such a shitty deal.”

“Christ, Murdoch,” Tyler said. “After all our work, you can’t tell me you believe that.”

“Don’t you? I mean, down where it counts? When they came to you that night, didn’t some part of you want to go along? Even if you said no, some part of you thought, shit, I don’t want to live and die and never understand what it’s all about… Wasn’t it like that?”

“Stupid question.”

“Seriously.” He startled Tyler by stopping the vehicle, standing on the brake until they were poised motionless on the white line of this country road. “Cutting all the crap,” Murdoch said.

Tyler just stared.

“What do you think we’d find,” Murdoch pressed, “if we turned around and drove back into that little pissant town?”

“Some evidence of our ability to harass an enemy. Were you asleep when you fired that TOW?”

“So we knocked down one of their ducks. I’m sorry, Colonel, but big fucking deal. How long till they send another Helper? They can have another unit there in a couple of days. Probably hours. They’re that efficient. The more I think about this, the more pointless it seems. The only reason we get away with it is that they don’t care. We’re like fleas on an elephant. Too insignificant even to scratch.”

He jerked the Hummer into a U-turn. Tyler said, “You really mean to go back there?”

“We need supplies. We should have stopped before we fired that missile. Plus I’d like to see just how long it really does take to repair the kind of damage we’ve been doing. Think of it as target assessment.” He gave Tyler another long look. “If you don’t mind, Colonel.”

Tyler minded a great deal, but he didn’t say so. It might be dangerous to linger at the site of an attack, but it might be more dangerous still to override Murdoch when the younger man was in this hostile mood.

Everything since Contact had become a matter of balances, Tyler thought. One thing weighed against another. What was buoyant might suddenly sink; what fell might rise.

* * *

They parked the Hummer out of sight– Tyler’s precaution—in the service bay of an Exxon station. Because Murdoch intended to stay the night in this village, they located two adjoining rooms in the brick hotel overlooking the remains of the Helper. The hotel was empty. The afternoon sky was dark and the corridors rattled with the sound of distant thunder.

Murdoch left to scrounge for food. Tyler stayed in his room, dwelling on the problem of the younger man’s doubts.

Maybe he should have seen this coming. Murdoch had been a technician in his old life, more loyal to the weapons he maintained than to the abstractions they served—the country, the Corps, the national defense. It was a thin reed to cling to, and lately Murdoch had grown sullen. The decline had been gradual but marked.

Maybe it was predictable. All the standards had fallen, Tyler thought. There was no propriety anymore, no decency. The norms had become fluid.

It was a frightening thought. Tyler had spent a lifetime negotiating the borderline between sanity and compulsion, and he had learned what Sissy in her madness had forgotten: Appearances matter. In the question of sanity, you were allowed to pretend. You were supposed to pretend. Everyone pretended. We prove we’re sane by pretending to be sane. To fail at the pretense, or not to bother, was the definition of insanity.

But now… it was as if gravity had failed, as if every solid thing had come unhooked from the earth. In an empty world, who was to judge? Where were the boundaries to separate one thought from another? What impulse might surface unobserved? How to distinguish the daylight from the dark?

We’re naked in this place, Tyler thought, and God help us for that.

He dozed for a time on the hotel bedspread and woke with a skull-splitting headache.

Murdoch came in the door with bags of canned food and bottled water. He dumped these on the bureau and took a towel from the bathroom—he was wet, his hair streaming water; it had begun to rain.

“It’s funny,” Murdoch said. “Most of the towns we’ve been through, you see at least a couple of people. This place—I’d swear it’s deserted. Didn’t see a living soul out there. For a while I thought I heard music. But I couldn’t track it down—not in this weather.”

Murdoch toweled his hair vigorously. The window was open a notch, and the room smelled moist and cool.

Murdoch gave him an odd, cautious look. “By the way, Colonel, have you seen the Helper?”

Tyler came alert. “What about it?”

“Well, it’s doing something,” Murdoch said.

“We destroyed it—what could it be doing? 7’

“Well, sir, it’s more or less putting itself back together.”

* * *

A.W. Murdoch followed Tyler down to the lobby, where the Colonel stood rigidly at the shattered front window and stared across the road at the remains of the Helper… at all that black, sooty dust that had begun to move as if stirred by an imperceptible wind, to heap itself into a crude, wet mound where the Helper had been.

Murdoch hadn’t been too surprised to see the Helper putting itself together. All the Traveller technology seemed to use subordinate but independent parts—the octahedrons, which were part of the Artifact; the Helpers, which were smaller fractions of the octahedrons… and all this. impact dust, which was just the smaller constituents of the Helper, he guessed, mobile and smart enough to crawl back into the original order.

Or the microbes that had infected everybody, come to that. Murdoch supposed those were machines, too, tiny but intelligent. There must be some irreducible level—a disorganization from which a Helper, for instance, couldn’t recover—but they hadn’t achieved that with a simple TOW.

Murdoch thought, It’s like punching mud. We should have known.

But Tyler hadn’t known, and Tyler was plainly horrified. He stood at the frame of the broken window shaking his head. Murdoch approached the older man cautiously. “Colonel?”

“Is it a threat?” Tyler said. “Are we in danger from it? Maybe we ought to move on.”

“I don’t imagine so. I don’t think we really damaged it. I doubt we even annoyed it. If these things carried a grudge, we’d be dead by now.” He felt a little guilty for breaking this news to Tyler in such an abrupt way; he felt he should make up for it. “Sir, we might as well go upstairs. You’re getting all wet. Cook us some food up there. I got some Coors from the grocery.”

When Tyler decided to leave D.C., they had assembled a kit that included a hot plate, pots and pans, plastic cutlery Upstairs, Murdoch plugged in the hot plate and started frying eggs. The hotel room filled with the smell of hot butter.

Tyler cracked open a beer and stared out the window. His manner, Murdoch thought, was frankly a little crazed.

Murdoch had decided weeks ago that Colonel Tyler might not be firing on all cylinders, but so what? Who was? Maybe all the sane people accepted that nighttime offer last August; maybe only a pair of lunatics would be driving around the country taking shots at these machines, like two kids soaping windows on Halloween.

He came to understand that Tyler lived in a world of orders given, rules obeyed, limits respected—a world as fragile as the egg Murdoch had just cracked and as hard to repair. Naturally, Tyler was finding it hard to adjust.

“My father only gave me one piece of advice in his life,” Murdoch said, “and that was to play the hand they deal you. I think he got it from a song. Or Dear Abby. But you can’t argue with it, right? Colonel, we got a shitty hand here. But we’re not dead yet.”

Tyler looked away from the window. “You never talked about your father much, Mr. Murdoch.”

“Not much to say.”

“What did he do for a living?”

“Raised sinsemilla up in Mendocino County.” To Tyler’s uncomprehending look Murdoch added: “He grew marijuana.”

“Christ. Really?”

“Honest to God.”

“He was a drug dealer?”

“Well—more like a bootlegger. That was the spirit of the enterprise.”

Tyler absorbed this information. “He must have hated it when you joined the Marines.”

“I can’t say it pleased him. But he told me it was my life, I should make my own mistakes. When I got on the bus at Ukiah, he said, Try not to shoot anybody!’”

And I never really did, Murdoch thought—unless you count the Helpers. Even then, he hadn’t done them much harm, apparently. Tyler shook his head. “It’s always a surprise. People’s families.”

“You don’t talk about your own family much.”

“No,” Tyler said. “I don’t.” Murdoch let it drop.

He served the eggs; but Tyler put his plate aside. “Sir,” Murdoch said, “speaking frankly, are you all right?”

The Colonel, who had been sitting stoop-shouldered in the chair by the window, drew himself up, almost into a sitting brace, his chin tucked, frowning, as if the question had stung him. “Of course I am.”

And they ate in silence and listened to the hiss of the rain on the window.

* * *

Murdoch told the Colonel he thought they should stay in Loftus until the cold rain passed, and Tyler had surprised him by agreeing. It seemed to Murdoch that the Colonel had grown both very unhappy and very agreeable recently.

Privately, Murdoch was curious about this little town. There were some questions that had piqued his interest during this shooting-gallery trek across the South, and he hoped to find some answers here.

For instance, exactly what was happening to the people in these little road towns? Where were they going? They weren’t on the highway, for sure; the highways were deserted. But so—increasingly often—were the towns.

Tyler disliked these questions and refused to discuss them, but Murdoch was simply curious.

In the morning he left the morose Colonel and wandered out into the street.

The rain had eased, but the sky was dark and restless with cloud. While he was asleep, the Helper had achieved a blurry approximation of itself. Minute grains of black dust moved over its surface, giving it the look of something swarmed by insects. It was as strange as anything Murdoch had recently seen, but he was growing accustomed to miracles… he watched for a moment, then shrugged and turned away from all these shattered storefront windows.

Yesterday there had been music. He’d heard it while he was scrounging for food at a grocery store a couple of blocks from here. The music had come very faintly through the rain, and Murdoch guessed it might have been imaginary, the kind of thing you hear when you’re alone in a strange place in a storm… but he remembered it as music, faint but unmistakable.

Today, he stood still and listened.

There was a faraway bark of a dog. A few wind sounds. The grit under his shoes as he shifted back and forth. No music. Spooky.

He turned a corner away from the main street. He had decided that today he would find somebody—a human being or a Contactee, it didn’t matter. Murdoch just wanted to look at a new face, ask some questions. The name of this little street, posted on a rusty sign at the intersection, was elm. Every one of these towns had an Elm, or an Oak, or maybe a Peach or a Magnolia as they pressed on into Georgia. What better place to find out what had happened to everybody? Everybody lived on Elm. He decided to knock on the door of the first house he came to.

The first house on Elm was a little bungalow with a tiny front yard. It had a wooden porch, and on the banister, five terracotta pots of dead flowers. Murdoch stepped up onto the sagging porch and nudged aside a child’s red wagon. He pushed the doorbell and listened as the buzzer rang inside.

Nothing stirred.

He opened the screen and knocked at the door. The sound of his knock seemed to make the silence heavier.

“Hey!” he said. “Hey, anybody in there?”

This was a strange thing to be doing, and he was suddenly aware of himself—a lonely figure, thin in his ragged uniform, his hair grown long and his stubble unshaven. Christ, he thought, I must look like a scarecrow. What if somebody did open the door? One look at me and they’d close it in a hurry.

But no one answered his knock.

He tried the knob. The door was locked.

He looked up and down the street. He’d never broken into a house before. Well, fuck it, he said to himself. I’m coming in there. Heads up, you ghosts.

He put his shoulder against the door and pushed. The door was old, and wood rot had gotten into the framing of it. The latch sheered out of the molding with a creak and a snap. Murdoch peered into the inner darkness.

Who had lived here? Somebody with kids, judging by that wagon. The room inside, now dimly visible in the watery daylight, was dusty but reasonably tidy. A brick-red sofa stood against one wall. Above it hung a framed oil color of a woodland sunset. There was a TV set, a stereo, an empty fish tank. Some kids’ toys were scattered on the floor.

Also on the floor…

Murdoch stared at it a long time before he recognized it for what it was: A human skin.

* * *

After he vomited over the porch railing, Murdoch selected a long willow branch from among the windfall on the neighbors’ lawn. He was reassured somewhat by the weight of the stick in his hand. He was otherwise unarmed—but what was there to shoot at?

All up and down this rainy street, nothing moved.

Murdoch clutched the stick and forced himself to climb the three steps up to the porch, to cross the intervening space to the door, open it, step once again into that terrifying dimness.

The skin lay at his feet. It hadn’t moved.

But it was definitely a skin. Fragile, empty—almost transparent. But human, Murdoch thought. Its shape was difficult to discern; it was folded into itself, accordioned together; but one arm projected, a fragile white papyrus, with a hand like an empty glove and five delicate, pale fingers.

It reminded Murdoch of a discarded skin of a spider he had once found in an empty locker—spider-shaped, but so delicate that a breath would carry it away.

He lowered the willow branch until it was almost touching the empty human skin, then pulled it back, revulsion winning out over curiosity.

He stepped over the hideous thing and deeper into the house.

The house was a bungalow with only a few rooms: this living room, the kitchen, two bedrooms, a bath. Murdoch investigated them all, flicking on lights where the daylight didn’t reach.

He found two more skins: one in the kitchen; one—smaller, which made it somehow more horrible—in the child’s bedroom.

Leaving that room, he felt dizzy; and realized he’d been holding his breath as if something in the house might infect him… might suck away his substance, might drain him as thoroughly as these people had been drained of themselves.

He hurried to the door, but stopped there.

He turned back. He took a firm grip on the willow stick and held it with its narrow end pointed at the first of the skins.

The urge to poke at the thing was as strong as the urge to turn and run. There was something childish about this, Murdoch thought. He was like a little child poking at a rattlesnake’s shed skin. He dreaded it… but he couldn’t help wondering about it. Would it crumble or would it fold? If it broke at his touch, would it make a sound? Would it move in leathery fashion, like parchment, or would it rattle like sun-bleached cellophane?

He touched the skin with his stick.

In fact, it made only the faintest noise as he turned it… a whisper of membranous surfaces, like the murmur of leaves in an autumn tree, or the turning of a page in an old dry book.

Murdoch thought he might vomit again. He turned and stumbled to the porch railing.

That was when he saw the girl.

* * *

“You don’t look so good,” she said.

Murdoch didn’t think he could stand much more startlement. One more shock and his ventricles might explode. He looked up from the railing with a terrible, emasculating dread.

But it was only a girl, standing on the sidewalk with a frown of concern.

A local girl, judging by her accent. She wore a too-big man’s windbreaker over a yellow T-shirt. Her blue jeans were tight, and she had sneakers on her feet. Murdoch pegged her at about eighteen, but she might have been younger or older. Her head was cocked and she was studying him with patient sympathy.

“You found those skins in the house, huh? First time you seen one?”

She was pretty in a stringy-haired kind of way. Her face was a perfect oval and her eyes were intelligent.

Murdoch tried to reassemble some masculine composure. “First time,” he admitted. “Christ! You’ve seen them before?”

“Yup.”

“Scary as hell.” She shrugged.

The nausea had passed. Murdoch straightened and undamped his hands from the railing. “You, uh, live here?”

“No—not this house. This’s where the Bogens used to live.” She pointed: “I used to live a couple doors down. But I moved out of there. Guess where I live now!”

He felt like saying: Girl, there are three dead people in this building—nothing left but their packaging. Under the circumstances, maybe a guessing game kind of verged on bad taste.

But here was a new face, which was what he’d set out to find, and he didn’t want to chase her away. “I can’t guess.”

“The Roxy,” she said.

The Roxy? A theater? Did this town have a Roxy Theater? Was there an old trestle town like this that didn’t?

“I turned the manager’s office into kind of an apartment,” she said. “And I taught myself how to run the movies.”

He said, “You were running a movie last night? Last night when it was raining?”

She brightened. “How’d you know?”

“Heard the music.”

“It was 42nd Street.There was an old-movie festival playing when Contact came. Those are the only films I can find. I got 42nd Street and Golddiggers of1934 and The Maltese Falcon.I don’t play ’em much. It’s pretty hard work by yourself. And if you see ’em too often, what’s the point? But on a cold night like that…”

“I understand,” Murdoch said.

“Already, I could sing that 42nd Street song in my sleep.”

“Uh-huh. Hey, what’s your name?”

“Soo,” she said. “Two ohs. It’s not short for anything. Soo Constantine.”

“I’m A.W. Murdoch.”

“What’s the A for, A.W.?”

“Abel,” he lied.

“Mmm… I like A.W. better.”

“So do I. Soo, tell me—are there more of those, uh, those—”

“Skins?”

“Are there more of those skins around?”

“Most every house,” she said. “If you look. I hope you’re not planning to look.”

“No, I just… well, Christ, it took me by surprise. I mean, is everybody in town like that?”

“Nearly. ’Cept me.”

“Well, what happened to them? Do you know?”

“They left, A. W.,” she said flatly. “They went away. But not their skins. They just used up their bodies and they left their skins behind.”

* * *

“A radio,” Colonel Tyler said. “Maybe that’s something we ought to have.”

Murdoch, cooking dinner over the hot plate, wondered what this might portend. “Sir, a radio?”

“To contact other people. Other human beings.”

Tyler sat in the hotel chair where Murdoch had left him this morning. He hadn’t shaved, which for the Colonel was a serious omission. Murdoch had pegged Tyler for the kind of man who’d shave in a hurricane and stock the storm cellar with Aqua Velva.

“I think we need that contact, don’t you, Mr. Murdoch?”

“Sir, how many of those Coors have you been into?”

Tyler looked at the can in his hand, then set it aside. “What are you suggesting?”