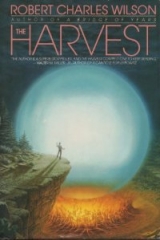

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

This wasn’t about Lillian. Jim sounded too disturbed. Not having-a-baby disturbed. There was a darker note in his voice.

Matt checked his watch. “Rachel’s home from school and she said she’d fix dinner tonight. Maybe we could have lunch tomorrow?”

“I’d prefer tonight.” Pause. “I’m working shift hours, but how would it be if I stopped by on my way home?”

“How late?”

“Eleven, say. Eleven-thirty.”

“It’s important?”

“Yes.”

Not maybe or sort of, Matt thought. Flat yes. It made the small hairs on his neck stand up.

“Well, yeah,” he said. “I’ll be looking for you.”

“Good,” Jim said, and promptly hung up the phone.

* * *

He caught Annie as she headed out the door.

When he told her about the party Friday night, she smiled and said she’d be there. It was the familiar Annie Gates smile. She thanked him, touched his arm. He walked her to the parking lot.

By God, Matt thought, we may be on-again-off-again, but I do believe at the moment we are definitely on.

He was surprised by the pleasure he took from the thought.

She gave him a brief hug as she climbed into her Honda. The touch was therapeutic. It wasn’t good to be alone, Matt thought, when the world had taken such a curious turn.

Chapter 2

Brookside

In December 1843, when the explorer John Fremont was mapping what would become the state of Oregon, he descended in a single day from a howling snowstorm in the high Cascades to a lake surrounded by soft green grass—from winter into summer. Winter Rim, he called his starting point, and Summer Lake, where his party pitched camp for the night.

A century and a half later, the state was still defined by its geography. The Willamette Valley, heartland and breadbasket, ran between the Cascades and the Coast Range for 180 miles south of Portland. East of the Cascades was a parched, cold desert. West of the Coast Range was coastal Oregon, 280 x 25 miles of farmland, forest land, and isolated fishing villages.

Buchanan was the largest of the coastal towns, a forest port situated on a broad, shallow bay. It had grown with the Dunsmuir Pulp and Paper Mill (est. 1895) to a population approaching 40,000 at the end of the twentieth century. Its shipping docks handled a respectable Pacific Rim trade, and its fishing fleet was the largest south of Astoria.

Buchanan had begun to cross the demarcation point between town and city, with all the possibilities and problems that implied: diversity, employment, anonymity, crime. But the municipality still held its Fishing and Logging Festival every July, and the local radio station still broadcast tide tables and Salmon Bulletins between sessions of softcore C W.

Like every town on the Oregon coast, Buchanan was accustomed to rain. Each winter, the ocean seemed to infiltrate the air. There was not just rain, there was a complex palette of mist, drizzle, fog, woodsmoke, and low clouds. Winter was the slow season, the melancholy season.

But even Buchanan occasionally saw a blue sky, and this summer had been drier than most. Ever since Independence Day, the town had basked under a dome of clear Pacific air. Reservoirs were low and a fire watch had been declared in the deep coastal forests. Crickets ratcheted in the brown fingers of dry lawns.

Afternoons evolved into long summer evenings.

Matt Wheeler’s thoughts had turned to Brookside Cemetery that afternoon, lingered a moment and turned away. Tonight he sat down to a meal of pan-fried steak and pondered a more immediate problem: that troublesome phone call from Jim Bix. Brookside had fled his attention.

It lingered in the minds of others.

Miriam Flett, for one.

Beth Porter and Joey Commoner, for two more.

* * *

SPEECH PROMISED ON SPACECRAFT

announced the headline in the Buchanan Observer.

Miriam Flett spread the front page across the kitchen table and attacked it with the pocket razor she had purchased this morning at Delisle’s Stationery in the Ferry Park Mall.

Miriam appreciated these disposable pocket cutters, a tongue of stainless steel that slid in and out of a round plastic sheath as you touched a button on the side. They were 590 each in a bin on the counter at Delisle’s, and they came in different colors. Miriam bought one every week. This week, she had chosen blue—a calming color.

The blade, not calming, was as bright and sharp as a claw.

Miriam attacked the newspaper. Four neat slashes separated SPEECH PROMISED from the lesser SHELLFISH POISONING SUSPECTED and LUMBER INDUSTRY FORESEES SLUMP.

She inspected the bottom-right corner of the article for a continued p. 6 or similar words—continueds were always annoying. But there was no such notice.

Good, Miriam thought. A good omen.

Miriam did not precisely understand the nature of the work she had undertaken, but she understood two things about it. One: It was important. And two: Neatness counts.

* * *

If Beth Porter and Joey Commoner had come roaring along Bellfountain Avenue on Joey’s Yamaha motorcycle—but they didn’t, not until later—they might have seen Miriam outlined in the window of her small bungalow, clipping newspapers as the sun eased down, a compact gray-haired shape hunched over a scarred kitchen table.

Miriam had lived all her fifty-six years in the town of Buchanan. For nearly half of those years she had presided over the reception desk in the principal’s office at the James Buchanan Public School. Last year Miriam had been reprimanded for handing out religious tracts to the children waiting to be scolded by Principal Clay. Principal Clay (whose first name was Marion, and heaven help him if the truth behind “M. Jonathan Clay” ever escaped into the playground) had hinted to Miriam that early retirement might be a wise option. Miriam Flett didn’t have to be told twice.

Once upon a time she might have held on to that job with both hands—gripped it until her fingernails tore free. Miriam was not fond of changes in her life. But she supposed the Miriam who couldn’t tolerate time and change had died last year, when the Eye of God appeared in the sky.

The message in that advent had seemed quite clear.

Places change. People pass on. Love dies. The world becomes, in time, almost uninhabitably strange.

Faith abides.

She seldom attended church. It was Miriam’s opinion that the local churches—even the Truth Baptist, which people thought of as a fundamentalist church—misrepresented the Bible. Miriam believed in God, but she did not have what the television evangelists called “a personal relationship” with Him. The very idea frightened her. The churches made much of redemption and forgiveness, but Miriam had read the Bible three times through without discovering much evidence in those pages of a loving God. Merciful—perhaps. On occasion. But Miriam believed most profoundly in the scary God of Abraham and Isaac, the God who demanded his sacrifices in flesh and blood; who swept aside humanity, when humanity displeased Him, the way a farmer might spray his crops with Malathion to eradicate a persistent infestation of beetles.

These thoughts were vaguely on her mind as Miriam directed her eyes to the clipping before her.

The White House announced today that the President would address the nation amidst growing rumors of a new breakthrough in communication with the so-called alien spacecraft orbiting the Earth.

Similar announcements have been made by the leaders of several major powers, including President Yudenich of the Russian Republic and Prime Minister Walker of Britain.

These announcements have led to accusations of a high-level conspiracy to conceal information. In a speech to Congress, Republican Whip Robert Mayhew accused the President of—

But Miriam sighed and pushed the scrap of paper away. Tonight she seemed to have no relish for the news, particularly political news. She settled her bifocals on the table and rubbed her eyes.

The kitchen table had been much eroded by Miriam’s work. Over the course of a year, her cutter blades—bearing down a little too hard on this clipping or that—had stripped away slivers of Formica. The table had come to look like a butcher block, and Miriam regretted it. The kitchen, otherwise, was quite tidy. She had always believed in a tidy kitchen.

She picked up her eyeglasses and pulled her scrapbook closer.

This was the current volume, Volume Ten. The other nine were stacked on a hutch beside the table. The upper shelf held spice bottles and cookbooks; the lower shelf, her work.

It was not long after she left the school board’s employ—shortly after the Eye of God appeared—that Miriam began to understand that she was quite alone in the world: friendless in Buchanan, considered an eccentric even by the churches. Of her family, only her father had remained alive—and that barely. He had been living in the Mount Bailiwick Care Community, incontinent and incoherent, but Miriam had visited him every day, had talked to him even when his pupils dilated with foggy disinterest. She told him about her project.

“I’ve started clipping the papers,” she said, and watched him carefully for some tic of surprise or discouragement. There was none. Unshaven, he sat in bed and looked at Miriam with the same passive stare he directed at the TV set as soon as Miriam left the room, or before she arrived.

Emboldened, she went on. “I think it’s what I’m supposed to do. I can’t explain how I know that. I don’t suppose anybody told me to do it. But I will take all the newspaper writing about the Eye of God and I’ll put those clippings in a book. And at the end of all this it will remind someone what happened. I don’t know what the end will be, or who will need to be reminded. But that’s what I’ll do.”

In the old days, Daddy would have had some answer. He used to have quite a lot to say about Miriam’s projects, almost always disparaging. Miriam had never quite lived up to Daddy’s expectations.

Since the stroke, however, Daddy had had no expectations whatsoever. Miriam could say and do what she wished—even in this room.

She had wished to quit her job when Principal Clay accused her of fanaticism. She had done so. She had wished to keep a scrapbook. So Miriam had done so.

She pulled down Volume One from the shelf. It was little more than a year old, but the newsprint inside had already begun to turn brittle and yellow.

All these clippings were from the Observer, mostly labeled UPI or Reuters. Miriam could have had more clippings if she’d taken a Portland paper or gone down to Duffy’s for The New York Times. But the point of the exercise wasn’t more. The point was enough.

NASA MYSTIFIED BY OBJECT IN SKY

Her first and fondly remembered. Miriam turned a page.

NOT NECESSARILY HOSTILE SAYS U.N. COMMITTEE

FEAR SWEEPS WORLD

MOBS TOPPLE GOVERNMENTS IN JORDAN, ANGOLA

Miriam turned a whole sheaf of pages.

NEW YORK CITY RESCINDS CURFEW;

PANIC HAS SUBSIDED SAYS MAYOR

Such a sweep of history enclosed in these books! She skipped ahead to Volume Three. By Volume Three, the screaming headlines were more sparse. Many of the clippings were from the Features section. So-called opinion pieces. In Miriam’s opinion, worthless. But she had collated them faithfully.

LIFE IN UNIVERSE INEVITABLE: SAGAN

Astronomer and popular writer Carl Sagan argues that the events of the past six months were “inevitable, in one form or another, given overwhelming odds that life has evolved elsewhere in the galaxy. We ought to be grateful that this has happened in our lifetime.”

Sagan does not see the artifact as a threat. “It’s true that no attempt at communication has been made. But recall that any journey between stars must take an immensely long time. The entities responsible must be capable of exercising an enormous patience. We should try to do the same.”

But Miriam recognized that song: it was a lullaby, whistled in the dark. Clipping the Observer, Miriam had grown tired of Sagan and all the other pundits to whom the media had so eagerly flocked. In the end, they were as plainly ignorant as everyone else. And as plainly misguided.

It is an Eye, Miriam thought, and was there any question just Who was peering through it? And an Eye must have a Hand: of Judgment. Volume Six.

April and May of this year. A very fat volume indeed.

ALIEN ARTIFACTS IN MAJOR CITIES

But the photographs told the tale best. Here was a telescopic view of the so-called Artifact, starry dots emerging from it like so much confetti or winter snow, a snow of some two hundred flakes dispersed equivalently across the world. Then, in the later pictures, not flakes of snow any longer but faceted obsidian structures hanging above all the world’s proud hives– New York, Los Angeles, London ; and Moscow, and Mexico City, and Amsterdam ; and Johannesburg and Baghdad and Jerusalem and too many others, all marked on a newsprint map of the world dated April 16. Grim octahedral slabs. Inhumanly perfect. They did not fly, veer, dash, dart, or glide; simply fell through the atmosphere like so many precisely aimed bubbles. They landed with the gentility of butterflies in available open spaces, and when they had landed they did not move. No visitors emerged. Having arrived, the octahedrons did nothing more spectacular than cast their own immense shadows.

Miriam supposed Mr. Sagan was continuing to advise patience.

It was not the Eye but these several Fingers of God that seemed to have worked an effect on the people of Buchanan. Miriam knew people had begun to take the Eye for granted, as people will take anything for granted if it stands still long enough. But the Fingers were a message. They said: Yes, I’ve come for a purpose. No, I’m not finished with you. And: I move slowly but inexorably and you may not lift a hand against me. It was a truth that penetrated the idiotic cheerfulness of her neighbors, a truth that bent, the backs of the proud and softened the voices of the mighty. The town of Buchanan seemed to acknowledge at last that this was the Endtime, or something like it—that nothing predictable would happen anymore.

Miriam opened Volume Ten to the first blank page and installed SPEECH PROMISED ON SPACECRAFT with a few dabs of her Glu-Stik, also from Delisle’s.

She hoped this was the only clipping from the Observer tonight. Miriam was tired. She had shopped for the week’s groceries today and felt worn out, maybe even a little feverish. Light-headed. The check-out girl at Delisle’s had sneezed three times into her hankie as Miriam was purchasing her cutter blade today. Miriam had paid with a one-dollar bill and hoped she hadn’t been handed a case of influenza along with her change. What were they calling it? Taiwan Flu? That was all she needed… what with the difficult times ahead of her.

But Miriam was dutiful and didn’t go directly to bed. Instead she turned the pages of the Observer and frowned through her bifocals at every article. There was nothing more for her collation in the first section. She observed with pleasure that Perdy’s, the big department store at the Ferry Park Mall, had stopped running their NEW MOON MADNESS sale ads with that ridiculous drawing of the Eye of God beaming at a Kenmore washing machine. Maybe Perdy’s advertising department had been talked out of this sacrilege. Or maybe they were just nervous—like everybody else.

Skimming Section Two, the only other section the Observer possessed, Miriam was startled by something she had not expected:

It was her father’s obituary.

Silly to be surprised. She had arranged for it herself. Daddy had been a respected instructor in lathe mechanics at the community college and Miriam thought his passing deserved notice in the Observer.

But the impending publication of the obituary, like so many of the other occasions and observances surrounding his death, had slipped from Miriam’s mind like a dew drop falling from a leaf.

Seeing the notice brought it all back. She had marked appointments on her calendar: a meeting Saturday with Rev. Ackroyd to arrange details of the memorial service. A check to the funeral director at Brookside. Notices to Daddy’s friends and colleagues, of whom only a handful were still living.

He had died Monday night in his sleep. The doctor at Mount Bailiwick said Daddy’s heart had simply stopped, like a weary soldier surrendering the flag. But she had not witnessed the death and still couldn’t encompass the simple fact of his absence.

There would be no more painful, wordless visits to his room. No more of the awful suspicion that his body had been vacant since the stroke—that he had been replaced by some respirating automaton.

But no more Daddy calling her name, either: not even the hope of it ever again. No smell of shaving soap and the razor white of starched collars.

No more his Try to do better today, Miriam, as she trudged out the door to school, woman and child.

Since the stroke, Daddy had been a ghost in a hospital bed. In death, he had evolved. When the man at Mount Bailiwick called to tell her Daddy died, Miriam had been startled by an involuntary memory of places: the house on Cameron Avenue where they had lived so many years, her room in it, her bedspread and her books, the way the lace curtains moved and sighed when she opened the windows on summer nights.

Things she had not thought about for thirty years.

In death, Daddy had entered into the world of all those lost things.

Sorely missed by his daughter Miriam, said the obituary. But that was only half a truth. All the unfulfilled expectations that had dogged her even in his hospital room—all those were gone, too. She had mourned him with tears the night he died… but mourned him also with secret relief and a childish, hidden glee.

She kept these feelings to herself, of course.

But the Eye—of course—could See.

* * *

She put the eviscerated newspaper in a pile to be bundled for the garbage. She filed Volume Ten in its place on the shelf.

She made a cup of tea. The sun was well down now. The sky was a transparent inky blue, the Eye already peeking through the big back window.

Miriam pulled the drapes.

She turned on the television and watched the ten o’clock news show, a Portland program on cable. But the anchors, a man and a woman, looked like children to her. Children playing dress-up. Where were the adults? Dead, probably.

She touched her forehead with the back of her hand.

I really am feverish, Miriam thought. At least a little.

She turned out, the lights, checked the lock on the front door, and retired to bed.

She was asleep as soon as she pulled the quilt around her shoulders.

She stirred only once—after midnight, when Joey Commoner’s motorcycle sped past the house, the sound of Beth Porter’s laughter mingling with the roar of the engine.

Miriam turned once restlessly and went back to sleep as the noise faded. But her sleep was not dreamless.

She dreamed of Brookside Cemetery.

* * *

At sunset, as Miriam Flett was gazing absently into the many volumes of her Work, Beth Porter stood at the south end of the parking lot of the Ferry Park Mall wiping her nose and waiting for Joey Commoner to show up.

She wondered whether she ought to be here at all. She felt hot and stupid in her leather jacket. She probably should be home lying down. She was sick, after all. Dr. Wheeler had said so.

The parking lot was empty—a lonely vastness in the last blue daylight.

The air was still hot, but the sky had a deep and vacant look, and by midnight there would be a cool wind running in from the sea.

Beth checked her watch. He was late, of course. Joey Commoner! she thought. You asshole! Be here.

But she still didn’t know what to do when he came.

Tell him to fuck off?

Maybe.

Go with him?

Maybe.

To Brookside? In the dark, with a motorcycle and this can of spray paint she had bought for no better reason than because he told her to? Well… well, maybe.

* * *

Ten minutes later, she recognized his bike making a noisy exit from the highway.

He zoomed across the parking lot driving gleeful S-curves, leaning with the motorcycle until it looked like his elbows would scrape the blacktop.

He wore a black helmet and a black T-shirt. The shirt was from Larry’s Gifts and Novelties on Marina, downtown. Larry’s had been what used to be called a head shop until they took away all the drug paraphernalia a few years ago. No more waterpipes, no more grow-your-own manuals. Now Larry’s specialized in leather pants, T-shirts illustrated with the gaudy iconography of heavy metal bands, and a few brass belt buckles in the shape of marijuana leaves.

Joey Commoner’s T-shirt showed a neon-blue screaming skull on a bed of blood-red roses. Beth couldn’t remember which band it was supposed to represent. She wasn’t into heavy metal or the Dead. Neither was Joey, really. She was willing to bet he’d chosen this shirt because he liked the picture. It was the kind of picture Joey would like.

He came to a stop a yard away with the engine roaring and bucking. What struck Beth as really bizarre was the combination of that shirt and his helmet. The helmet was gloss black and the visor was mirrored. It made him look utterly insectile. For lack of a face to focus on, your attention strayed to the shirt. To the skull.

Then he pried the helmet off his head and Beth relaxed. Just Joey. His long blond hair was matted by the helmet, but it came free in a gust of wind and trailed around his shoulders. He was nineteen years old, but his face looked younger. He had round cheeks and a lingering case of adolescent acne. Joey would have loved to look dangerous, Beth thought, but nature hadn’t cooperated. Nature had conspired to make Joey’s anger look like petulance and his hostility resemble a pout.

He stood with his bike between his legs and the setting sun behind him, waiting for her to say something.

Beth discovered her heart was beating hard. She felt as if she’d had too much coffee. Light-headed. Nervous.

The silence stretched until Joey took the initiative. “You sounded pissed off on the phone.”

Beth summoned all the blistering accusations she had rehearsed since she left Dr. Wheeler’s office. Eloquence fled. She struck to the heart of the matter. “You gave me the clap, you asshole!”

Incredibly, he smiled. “No shit?”

“Yeah, no shit, you made me sick, no shit!”

He stood there absorbing the information with his lip still curled in that faintly insolent smile. “You know, I wondered…”

“You wondered?”

“Well, it kind of hurts…”

“What hurts?”

He was beginning to sound like a twelve-year-old. “When I pee.”

Beth rolled her eyes. He was hopeless, he was really completely hopeless. It hurts when 1 pee. Well, damn! Was she supposed to feel sorry for him?

“So who have you been screwing, Joey?” He looked faintly hurt. “Nobody!”

“Nobody? You don’t get the clap from nobody.” He thought about it. “Last year,” he said. “My cousin took me to a place. In Tacoma.”

“A place? What, a whorehouse?” I guess.

“A whorehouse in Tacoma?”

“Yeah, I guess. Do we have to talk about this?”

She felt she could only repeat these verbal impossibilities he was pronouncing. She nearly said, “Do we have to talk about this?” Instead she gathered what was left of her composure. “Joey, you screwed a prostitute in Tacoma and gave me gonorrhea. I’m not happy.”

“It was before I met you,” he said. He added—grudgingly, Beth thought—Tm sorry.”

“Sorry doesn’t pay for the antibiotics.” She looked away. “It’s degrading.”

“I’m sorry. All right? What am I supposed to say? I’m sorry.” He pushed forward on the Yamaha’s seat. “Climb on.”

No, she wanted to tell him. It’s not that easy. Not just I’m sorry. Climb on. You can’t get away with that.

But maybe it was that easy, and maybe he could get away with it.

She felt something shift inside herself, the tumbling of a weight in the hollow of her stomach.

“You got the paint?” Joey asked.

She was condemned by the weight of the bag in her hand. She held it up to show him.

“Good.” He stepped on the starter until the motor caught and screamed. He lowered his helmet over his head. There was a second helmet strapped to the bike; Beth put it over her head and tucked her hair underneath.

Climbing onto the bike, she felt a sudden burst of something she realized was joy… the mysterious, dizzying pleasure of doing something she knew was wrong. Making a serious mistake, making it deliberately.

“Hurry up.” Joey’s voice was muffled by his visor and the roar of the bike. “Almost dark.”

She put the motorcycle between her legs and her arms around the bone and sinew of his hips.

* * *

He smelled like leather and grease and sweat and wind.

Beth remembered schoolgirl gab sessions, steamy telephone conversations, the inevitable question: But do you love him? The same question rattled in her head now, high-pitched and girlish and embarrassing. But do you love him, do you love him, do you love him?

Her first instinct was that the whole idea was ridiculous, even offensive. Love Joey Commoner? The words didn’t connect. It seemed to Beth that he was an inherently unlovable object, like… oh, a garter snake, for instance, or a bait shop, or a can of motor oil. Something only a grubby little boy could approach with affection.

But that was not the whole answer. If the question had truly been asked, Beth’s truest answer would have been something like: Yes, I do love him… but only sometimes, and I don’t know why.

She had met him last year during her first month at the 7-Eleven up the highway. Beth had divided the clientele into five basic types: little kids, high-schoolers, suburban family types, bikers, and “Pickup Petes”—the guys who drove pickup trucks with strange accouterments, roll bars or banks of what looked like kleig lights, and who wore those duckbill caps day and night. Joey didn’t fit any of these categories, not even “biker.” He didn’t ride a muscle bike and he didn’t travel with the bike crowd. He always came alone. He shopped for snack food: quarts of ice cream and frozen pies, usually, and almost always on a Friday night. She learned to expect him.

One Friday he got into an argument with a Pickup Pete who had parked his rig practically on top of Joey’s Yamaha. No damage had been done to anything but Joey’s sense of dignity and proportion, but Joey called the guy a “cross-eyed asshole” and spat out the words with such acidic clarity that Beth was able to hear him quite clearly through the window glass next to the checkout counter. The pickup guy’s response was inaudible but obviously obscene.

She had watched with startled interest as Joey hurled himself at the man, who must have been twice his age and nearly twice his weight. Suicide, she thought. He’s fucking crazy. But the b oy moved like a whirlwind.

By the time she remembered to ring for the night manager, the fight was over.

Joey, needless to say, had lost.

When she went off-shift at midnight, he was still sitting on the cracked sidewalk outside. His upper lip was split and dripping blood onto the dusty concrete. In the green-and-white glare of the illuminated 7-Eleven sign, the spatters of blood looked both ghastly and unreal—like alien blood.

She could not say why she stopped and spoke to him. It had seemed like a bad idea even at the time.

But, like many bad ideas, it had a powerful momentum of its own. Her feet paused and her mouth opened. “No ice cream tonight, huh?”

He looked up sullenly. “You saw that guy?”

She nodded.

“He was fat,” Joey said with a shudder of distaste. She learned later that this was one of Joey’s pet horrors: he was disgusted by fat people.

“Yeah,” Beth said, “he was.” She remembered the guy as a steady customer—remembered the distinctive way his jeans sagged below the cleavage of his rump. “Gross,” she contributed.

Joey’s look turned to cautious gratitude.

Later, Beth would realize that she had seen both sides of Joey Commoner that night. Joey the authentically dangerous: Joey who had called that impressive wall of flesh “a cross-eyed asshole” and leapt at him like a crazed monkey attacking a rhino. Joey had been all fingernails and spit and bony knees and her first fear had been for the bigger man.

And Joey the vulnerable, Joey the little boy. Joey bleeding on the sidewalk.

She wanted to mother him and she wanted to offer herself to him. The combination of impulses made her feel like the sidewalk was spinning. “How about a ride home,” she said.

“What?”

“Ride me home and I’ll fix up those cuts for you. I have Band-Aids and things. My name is Beth Porter.”

He climbed onto his motorcycle. “I know. I’ve heard of you.” Well, Beth thought, that fucks that up.

Same story all over again. She was inured to it; nevertheless it hurt. But he scooted forward. “Climb on,” he said. She didn’t hesitate and she concealed her surprise. She climbed on and felt the leather seat press up between her legs. “Joey Commoner,” he said.

“Hi, Joey.”

Zoom.

* * *

Tonight he took her south along the highway and across the bridge that spanned the Little Duncan River. He turned off the highway and circled back through a raw development of frame houses to the river’s edge. Beth hopped off the bike. Joey cut the motor and wheeled the vehicle down the embankment behind the concrete pilings of the bridge.

The air was quiet here. Beth listened as the crickets resumed their creaking along the riverside.

The Little Duncan followed this stony bed to the sea. South across an open field, beyond the hydroelectric towers, the lights of the houses looked too far to reach—the last margin of civilization. North beyond the river was only weeds and the greasy back lots of businesses fronting on the highway. East: the Duncan River cutting back into the foothills of Mt. Buchanan. West: the cemetery.

Joey knew what most high school graduates in the south end of Buchanan knew, that if you followed the Little Duncan beyond this rockfall and through the duckweed flats, you could sneak into Brookside Cemetery after the main gates were locked.

Joey took the can of cherry-red aerosol spray paint out of the bag. He balled up the bag and threw it into the moonlit flow of the creek. He tucked the can under his belt, to keep his hands free.

Beth followed him along the riverbank. She understood Joey well enough to know that talking was over: there would be no talking now, only motion.