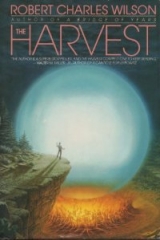

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

He hadn’t followed baseball since the 1978 World Series, the last time he’d owned a TV. The Yankees took the Dodgers that year, as Kindle recalled. Things had changed since then. He didn’t recognize names. Everybody looked too young. But he had watched the season progress on his hospital Sony, and he was determined to see the end of it.

Tonight it was an AL game, Detroit at New York. He thought Detroit looked good for the Series. He thought it would be a Detroit/Chicago Series, and his money was on Detroit.

The Tigers would take the Cubs, and then Kindle would pack up his possessions and move on.

* * *

He spent that night at the hospital, but he wasn’t sick enough to stay longer and he didn’t intend to. It was a charmless place at best. At the same time, it seemed pointless to move back to his cabin. He could get all the isolation he wanted much closer to town.

In the morning he phoned the local realty office. No one answered, but Kindle was ready for that. He knew a guy who worked there, or used to, a guy named Ira who sometimes hired his boat for fishing trips. Kindle reached him at home. Ira’s voice had the detached, bemused quality Kindle had come to expect from a Contactee. Kindle identified himself and came to the point: “Just a question, Ira, seeing as you’re in the business: Are houses free?”

“What do you mean… you want to buy a house?”

“Nope. I just want one. Yesterday I wanted a radio rig and I got one for free. Can I have a house?”

There was a pause. “Well.” Thoughtful. “I know of some empty properties. If you move in, I don’t suppose anybody will mind.”

“You’re shittin’ me!” Kindle couldn’t contain himself.

“Beg pardon?”

“Christ, you’re serious! I can move into any fuckin’ house?”

“Any empty one, I suppose.”

He recalled Joey Commoner’s remark about an antenna. “I want a house on a hill. No obstructions. Nice view all around.”

“Ocean view?”

“Doesn’t matter.”

“I can give you a few addresses.…” Kindle fumbled for his pen.

* * *

He spent the next day looking at properties. By mid-afternoon he’d picked one out: A two-bedroom frame house in Delmar Estates, a mildly upscale part of town, overlooking Buchanan and a northerly piece of the bay. The house was empty and unfurnished.

He moved in his single piece of property—the radio transceiver, still boxed. He put it in the middle of the living room floor.

The house had an empty-house smell. He guessed the broadloom had been cleaned before the property went on the market. Maybe the walls had been painted. He breathed in, breathed out.

He had never lived in such a place and never really wanted to… but he guessed a month or so here might be tolerable. Although, at the moment, there was nothing to sit on but the floor.

He drove to the Sears at the nearest mall and found the doors standing open but no one on duty at the cashiers’ stations. What else? He realized with some startlement that he could equip the house with any furniture he happened to like, price being no object. He’d always kind of admired these imitation-leather sofas, for instance. He tried one out, right there in the deserted Home Furnishings department. It was like sitting on a stuffed lizard. Sumptuous but probably sticky in hot weather.

But this was all academic—there was no way he could transport any of this stuff, not at the moment, not without grinding his bad leg down to bloody splinters. He sighed and moved on to the patio furniture. Two folding chairs and a chaise lounge, just about his speed. He tucked them under his arm and carried them to the car.

He went back for fresh clothes—a pair of jeans and an armload of cotton T-shirts and underwear.

It had been a long day and he was beginning to tire, but he made a second stop at the A P, where he picked up canned food, cold cuts, a couple of loaves of bread. The house was equipped with a refrigerator and stove… but hang on, was the electricity working? It hadn’t occurred to him to check the lights. He supposed he could phone the power company. If the phone was connected. If there was a phone. Okay, one more stop, back to the mall to pick up a touchtone telephone.

It was nearly dusk by the time he arrived back at the house.

Electricity, it turned out, wasn’t a problem. The refrigerator was humming vigorously. He switched on the kitchen lights and began putting away the food.

He noticed the wire shelves in the refrigerator were barely cool, and he frowned and checked the freezer. No frost. Not even a trace. Was that significant? Maybe it was a frost-free unit; Kindle had heard of such appliances, though he had never owned one.

But the refrigerator was humming like a son of a bitch. When he was here earlier… had he noticed that sound?

Maybe not.

Maybe, this afternoon, the electricity hadn’t been turned on. He plugged in the phone and called Ira. “Ira, I found a place.”

“I know,” Ira said cheerfully. “Up on Delmar. I was the listed agent on that property, by the way. Good view. I hope you’ll be happy there.”

“Pardon me, Ira, but how the fuck do you know where I picked to live?”

There was a pause. “The neighbors saw you leave some belongings. We assumed you were moving in.”

“What, you talked to the neighbors?”

“Well. In a way.”

By voodoo telegraph, in other words. “So tell me… did the neighbors also talk to the power company?”

“Well, Tom. Everybody more or less talks to everybody.”

“Well, Ira, doesn’t that more or less scare the shit out of you?”

“No. But I apologize if we alarmed you.”

“Think nothing of it.” He put the phone down in a hurry. Unfolded a chair and sat in it.

He’d forgotten to pick up a TV set. Was there a game on tonight? He couldn’t remember.

Kindle went to the kitchen, where the light was brighter, and unpacked the transceiver. Ungainly object. He tried to read the manual, but it was written in some language only theoretically English. “Do not allow to contact with moisture or heavily wet.” Words to live by.

He guessed Joey Commoner would be able to figure it out.

* * *

November was rainy; he postponed the chore of erecting an antenna. The ache in his leg retreated some. He began stocking up on groceries, beginning to suspect that Mart’s fears about the food supply were well-founded. The staples were still being trucked in, but luxury items had begun to disappear from the shelves. He stockpiled some of those, too. He felt like making a trophy list. Successfully hunted down in Buchanan, Oregon : Last bag of Oreos. Last bottle of gourmet popcorn.

He ferried down some items from his cabin, mainly tools and books. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire had been sitting where he left it last August and was a little musty, since he’d left the windows open, but still readable. A trudge through Gibbon might not be too bad, given all this rainy cool weather. Then on to Madame Bovary.

The Tigers took the American League pennant late that month.

He called Joey when the skies cleared for a couple of days.

“Been waiting to hear from you,” Joey complained. “I got a lot of tower parts from Radio Shack. And a beam antenna from Causgrove’s. But you weren’t at the hospital.”

Kindle gave the kid his new address. “You can transport all that?”

“Took a van out of the lot at Harbor Ford.”

Must do that myself one of these days, Kindle thought. “Are we talking hard physical labor here?”

“Some,” Joey said. “Bring beer,” Kindle said. “You got it.”

* * *

Kindle had worked erecting TV towers back in the sixties, and he remembered enough of that experience to temper Joey’s recklessness. He used a power drill with a masonry bit to anchor the antenna base in a concrete trailer pad in front of the house. He guyed the tower as it went up, extra guys on the first ten feet so Joey wouldn’t come plummeting down. Probably Matt Wheeler would resent being called in on another broken leg. Would resent it even worse if he lost one of his one in ten thousand—even if it was Joey Commoner.

They had the tower stabilized and the antenna installed by dusk. Joey did all the climbing, in deference to Kindle’s leg, a nice thought, or his age, which was insulting; he was careful not to ask.

Joey stood back from his work. “This ought to give us good access to the twenty-meter band, which I guess would be the busiest band under the circumstances, though who knows?”

“I sure as hell don’t.”

Joey had taken off his shirt during the final guying of the tower. As they entered the house, Kindle read the tattoo on his right bicep. Neat blue letters.

WORTHLESS, it said.

“You believe that?” Kindle asked.

Joey shrugged his shirt back on and began fiddling with the back of the transceiver. Kindle cracked a beer, waiting for an answer that didn’t come. This would have been a good time to order in a pizza, he thought, except nobody delivered anymore. He wondered who in Buchanan had eaten the last delivery pizza.

He persisted, “It just seems like a strange thing to write on yourself.”

Joey put his head up from behind the transceiver. “Since when do you give a shit?”

“Don’t get hostile.” Anyway, Kindle’s attention had refocused on the dinner problem. “Maybe I could cook us up some hamburgers on that Jenn-Air in the kitchen.…”

“Cook whatever you want. Fuck!” Joey had jammed a screwdriver into the palm of his hand. He added some other words.

“Shouldn’t have written, ‘worthless,’ ” Kindle said. “Should have written, ‘Bad tempered little SOB.’ ”

“Fuck off,” Joey said. “I thought you liked to do electronics.”

Joey stood up. What was that on his shirt—a skull? Skull and roses? “It’s too many words.”

“Eh?”

“’Bad-tempered little SOB.’ Would have hurt too much.”

“Kid has a sense of humor,” Kindle said.

* * *

He cooked up hamburgers the way he liked them, with a startling amount of chili worked into the ground beef, an acquired taste, perhaps, but Joey just ladled on the ketchup and forged ahead. Kindle asked, “When do we power up?”

“I guess after we eat.”

“Might not be anything to hear.”

Joey shrugged. He had absolutely mastered that gesture, Kindle thought. He had a vocabulary of shrugs.

Kindle said, “If it’s one in ten thousand, how many of those are hams or have the sense to rig up a radio? I read a statistic in one of those library books. Maybe one out of six hundred adult Americans has a valid amateur license. So what does that come to after Contact? Fifty people in the continental U.S.?”

“How should I know?”

“Well, we don’t know. But it can’t be very many. And how many of those are on the air?”

“More at night,” Joey said. “Reception’s supposed to be better at night.”

“Even so. Some of them are bound to be out of range or at the wrong angle to the antenna or some damn thing. Some of them maybe tried and gave up. We might not hear a blessed word.”

“Might not,” Joey said.

“What, you don’t give a shit?”

Joey seemed to ponder the question. “I want to work the transceiver,” he said finally. “You need somebody to talk to.”

“So as far as you’re concerned, this isn’t about saving the world.”

“Is that what you think?”

“No,” he admitted. “It’s maybe what Matt Wheeler thinks.”

“Stupid idea,” Joey said. “Is it?”

“Everybody’s gone already. I mean they’re still here, but they’re gone. Some of us just got left behind. We can’t do anything about it.”

“Help ourselves, maybe.”

“If we were that smart, we would have gone to heaven like everybody else. There’s a reason we got left here. All the important people are gone, and we’re still here because basically… because we’re…”

“What?”

Joey smiled. “Worthless.”

* * *

Joey switched on the radio, but the twenty-meter band was empty. All that static gave Kindle a chilly feeling. Little crackles of who knows what—interstellar radiation, cosmic noise, like rain on a rooftop, faint as memory. It was like listening to the restless sleep of the world.

It wasn’t just Buchanan that had gone strange, it was the entire planet. You could know that—he had known it for months—and still not feel it. But he felt it now, listening to the radio hiss like waves on an empty beach.

This was the silence of Detroit and Chicago, the silence of Washington, the silence of Ceylon and Baghdad and Peking and London.

We must have been the most talkative species for light-years around, Kindle thought, but tonight the Earth was as still as an empty church.

He heard what he thought was a snatch of voices amidst the static… but when Joey tuned back, there was nothing. “Try putting out a call,” Kindle suggested.

Joey took up the microphone. He cleared his throat. “Calling CQ,” he said, then covered the mike with his hand. “I feel like an asshole!”

“I expect everybody does the first time. Carry on.”

“Calling CQ. This is—” He covered the microphone again. “We don’t have a call number.”

“Just say your name, for Christ’s sake! Say we’re in Oregon.”

“CQ, this is Joseph Commoner in Buchanan, Oregon, calling CQ.”

Joseph?

“CQ, if anybody can hear me, calling CQ.”

* * *

Kindle sat through a couple of hours of this, then told Joey he was going to bed. “When you get tired you can crash on the chaise lounge if you want to.”

Not that Joey showed any sign of wanting to sleep. He continued to patrol the twenty-meter band with an obsessive glaze in his eyes.

Kindle brushed his teeth and stretched out on a mattress he had ferried here from the mall. He closed his eyes and listened to the sound of Joey calling CQ in the next room.

He thought about the antenna, about Joey’s radio waves zooming off into the dark night. Seek you, seek you.

Just the idea of it gave him the lonely shivers.

* * *

Kindle got up at dawn. Joey, curled on the lawn recliner in the living room, slept till noon. When he woke he came into the kitchen looking smug.

“Any luck last night?” Kindle asked.

“I talked to a couple of people,” Joey said, and checked out Kindle’s reaction with a sideways glance.

“No shit?” Kindle said. “Who?”

“A guy, a ham, in Toronto. That’s in Canada, right?”

“Last time I looked at a map it was. What’s happening in Toronto?”

“He says the situation is about the same as here. We’re supposed to talk again tonight. Ask him yourself. And another guy, down in Georgia.”

“Southerner, huh?”

“Well, he’s travelling around,” Joey said. “He’s an Army Colonel. Name of Tyler.”

* * *

Some nights later, Kindle watched the final game of the World Series on his color TV.

It was a Tigers/Cubs series, as he’d predicted. The game was broadcast without narrative, which gave it an eerie atmosphere. The only sound was the crack of the bat, the murmur (not a roar) of a sparse crowd.

All these games had been close. Pitchers’ games, Kindle thought. Scientific. Mistakes were few and counted for much: If a breaking ball stayed up and over the plate, it was bound for glory.

Detroit took the game 2-1 in the eleventh inning, winning the series.

Last at bat for the Boys of Summer.

The final score rode up the screen… then, suddenly, there was static.

Nothing on TV tonight, Kindle thought. Nothing on TV tonight ever again.

He phoned Matt Wheeler and told him he’d stay till Christmas.

Chapter 20

Christmas

Matt Wheeler saw less of his daughter Rachel as winter settled in. She was out of the house much of the time. She seldom told him where she was going or where she slept at night. Matt seldom asked.

They talked occasionally. He appreciated the effort she made, but increasingly it was dialogue across an invisible wall.

“Daddy,” she told him, “you have to talk to the Helper.”

He thought: Talk to it? What—that statue?

The Helper had stood in the City Hall Turnaround like a piece of grim abstract sculpture for weeks now. It neither moved nor spoke. “If you talk to it,” Rachel said, “it’ll talk back.”

“That’s… difficult to believe.”

“You have to talk to it,” Rachel said. “It can tell you things I can’t, and it’ll be here when I’m gone. That’s what it’s for.”

* * *

The rain was nearly constant now. On the day he closed the hospital, the second of December, Matt posted a sign at the Emergency entrance. His name and phone number were written in red letters under a waterproof plastic sheath. The number would reach him at home or in his car, as long as the telephone and local cellular system survived. He was considering the possibility of fitting a mobile medical unit in a hospital ambulance, or trying to locate the hospital’s own rural treatment unit, abandoned somewhere after Contact. But there didn’t seem to be a pressing need. The hospital’s facilities were intact if he should need them… though he could foresee a time when the town would exhaust its supply of drugs, of sterile needles—of doctors, perhaps.

On his way home, thinking about what Rachel had said, he stopped at the City Hall Turnaround.

The center of this traffic circle had been developed as a park, planted with grass and equipped with a water fountain and a plaque commemorating the town’s incorporation. Much of Willy’s IWW battle had been fought on this circle of alkaline soil.

The Helper stood here. It had floated into town along the coast highway, made a right turn where the highway crossed Marine, glided past Mart’s office in the Marshall Building and across the railway overpass, and stationed itself on the Turnaround green.

Matt walked toward it through the rain. The rain was cold; he shivered under the wet bulk of his overcoat.

He stopped a short but wary distance from the Helper. He was intimidated by its size—it stood at least seven feet tall—and by its glossless black surface, somehow untouched by the rain.

They called it a Helper. The name, he thought, was grotesque but appropriate. It suggested a blunt, totalitarian benevolence—a meaningless gesture from a humorless tyrant.

Talk to it?

Not possible.

He stood in the park a while longer, listening to the rain as it fell on the grass and watching the clouds roll down from the slope of Mt. Buchanan. Then he turned and walked back to the car.

* * *

Hard times coming. Rachel repeated the warning a few days later. “The Travellers are doing things to the planet,” she said, and Matt experienced a tremor of fear that stitched into the deepest part of him. It wasn’t what she said—though that was frightening enough—but how she said it: blandly, if not happily.

They were sitting in the living room looking past the blank TV set, through the window to a faraway ridge of wet Douglas firs in their dark-green winter coats. It was another rainy December morning.

Matt cleared his throat and asked what “doing something to the planet” might entail.

“Fixing it,” Rachel said. “Restoring it. Reversing all the changes. What we did over the last century or so—what people did—was to set forces in motion we couldn’t control. Global warming, for instance. The Travellers are taking some of the C02 out of the atmosphere and trying to bind it into the ocean.” She turned to face him. “It was worse than we suspected. If the Travellers hadn’t come… it would have been awfully hard for all of us, next century, or the century after that.”

“They care what happens to the Earth?”

“They care because we care.”

“Even if you’re leaving?”

“It’s where we were born,” Rachel said. “It’s our planet. And it won’t be entirely empty.”

“Restoring the balance,” Matt said. “That doesn’t sound so bad.”

“No. But in the short term… Daddy, I can’t explain all the things they’re doing, but in the short term, it could mean some chaotic weather, at the very least. Storms. Bad storms.”

He nodded, grateful for this nugget of hard information. “When?”

“I don’t know… maybe soon. Late winter, early spring.”

“There’ll be some warning?”

“Of course. That’s what the Helpers are for… one of the things they’re for.” Her expression now was not bland at all; she regarded him with a desperate unhappiness. “Daddy, you must talk to the Helper.”

* * *

It had been agreed at the November Committee meeting that they would gather to celebrate Christmas Eve at Tom Kindle’s new house in Delmar Estates. Guests were welcome, even Contactees, especially family, and Matt asked Rachel to come along—but she declined.

He drove to the party through a chill, heavy rain that threatened to turn into hail, along streets grown ragged with winter potholes. He wondered whether he might be the only one lunatic enough to brave the weather. Some party. But there were other cars parked at the house; and Kindle welcomed him inside, took his coat, told him that, in fact, all ten members of the Committee had shown up, but nobody else: “Just us human beings. Which is probably just as well. Come on in, Matt. Everybody else got here early ’cause of the weather, I guess. Abby’s been here since two this afternoon, puttin’ up these goddamn Christmas decorations, plus that little plastic tree in the corner. Had me hangin’ bulbs and lights on it.”

“Looks good, Tom.”

“Looks like a fuckin’ department store, but there was no stopping her.”

Matt remembered the way Buchanan used to dress itself up for Christmas—tinsel across the avenues, pine boughs on the lamp standards.

“The punch is over there,” Kindle said, “but go easy for a while, we got a turkey in the oven and some radio calls coming in from the east—I don’t want anybody throwing up on the microphone.”

* * *

Dinner was festive. Even Paul Jacopetti seemed to have mellowed for the occasion. Matt sat between Chuck Makepeace, who was promoting the idea of a New Year’s reconnaissance trip to the waterworks and the power company, and Abby Cushman, who had taken most of the dinner chores on herself and was away from the table between courses.

Matt noted the way she fluttered over Tom Kindle, served him generously, asked his opinion of the gravy, the dressing, the plum pudding. (“Looks real good to me,” Kindle said. “Real good, Abby.”) She was married, Matt reminded himself, and had a couple of grandchildren living with her—but they were like Rachel, lost to Contact. It was no wonder she had adopted the Committee, and Tom Kindle in particular.

He gave a brief, sober thought to Annie Gates. He hadn’t spoken to her for months. He hadn’t wanted to say all the necessary things. All the things that amounted to: Goodbye, good luck, I loved you in my own fucked-up way but now you’re not human anymore. Surely silence was better than that.

Abby recruited Paul Jacopetti, Bob Ganish, and a reluctant Beth Porter to deal with the dinner dishes. Everybody else adjourned to the living room; Joey Commoner began warming up the transceiver, scouting for stray voices prior to the east-west hookup scheduled for 8:00 Pacific time.

Kindle took Matt aside. “That Abby… she’s a pain in the butt. She’s been over three times this week. Stops to chat. I don’t know how to chat. She brings food. Matthew, she bakes.”

“She seems nice enough,” Matt said.

“Hell, she is nice. If she wasn’t nice it wouldn’t be a problem. She talks about her family—she doesn’t see ’em much anymore. She’s having a hard time and she needs somebody she can latch onto. And, you know, I’m only human. It’s been a while since I had a woman around, barring some Saturday nights in town, and even that’s all finished since Contact. So I think yeah, okay, Abby’s nice… but it’s not fair to her.”

“Why not?”

“Because I’ll leave. The only advantage to getting old is that you learn this shit about yourself. I was married once—little Coast Salish girl up in Canada. Lasted about six months. She went back to the reserve, I came back across the border. And that was pretty much the endurance record for Tom Kindle. Maybe I won’t leave this month, maybe not next month, but I’ll leave. And Abby’s been left too much just now.”

“Maybe you should tell her that.”

“Good advice. Maybe I should just club her down with a stick—it’d be kinder.”

“Or don’t leave. That’s the other choice.”

“Uh-huh.”

“The thing is, you’re useful around here.”

“Right. About as useful as half a crutch. Speaking of which, I’m still limping. Is that normal?”

“You’ll limp a while longer. But don’t put down your own contribution. You’re like an anchor at the Committee meetings. The radio’s been a morale booster, too.”

“Mostly Joey’s work.”

“And Joey, come to that. He’s turning into a human being. You treat him with a certain amount of respect. That’s a new thing for him.”

“You ever see that tattoo on his shoulder?” Matt nodded.

“’Worthless,’” Kindle said. “You suppose he believes that?”

He thought about it. He didn’t know Joey Commoner particularly well. Joey must have been eighteen years old when he had that word dyed into his skin, and it was precisely the kind of thing a pissed-off eighteen-year-old might do. It might mean nothing.

Still, if he had to render an opinion—“I think he might believe it, yes,”

Kindle shook his head.

“Shit,” he said finally. “I didn’t sign on to be anybody’s husband… and I sure as hell didn’t sign on to be a goddamn parent”

* * *

Come eight o’clock, Joey established contact with the community of survivors in Toronto. The weather was bad and the signal was poor; voices faded in ghostly fashion. But the contact across all that distance was heartening. Everybody gathered around the microphone and sang “Adeste Fidelis”—they had rehearsed this—and the Canadians sang “Silent Night” through the static. It was snowing there, the Canadian radioman said. The streets were knee-deep and the municipal plows weren’t out this year; the survivors were partying in a downtown hotel: “Lots of rooms and an emergency generator in the basement. We’re cozy.”

The Canadian chorus was bigger than Buchanan’s: perhaps eighty people, almost as large as the nearly one hundred in the Boston community Joey had contacted a few days ago. Which meant, Matt knew, there must be more such groups, but only a few of them had thought to attempt radio communication.

Toronto said “Merry Christmas” and signed off. Joey tried for Boston and a third contact in Duluth, but the weather wasn’t cooperating—“The skip isn’t in,” Joey said.

“We could phone ’em,” Kindle said. “Guy in Boston gave me his telephone number.” But the long-distance exchanges were unreliable these days and, anyway, a phone call wasn’t the same as radio contact; they could wait until tomorrow to pass on Christmas sentiments.

“Telephone service won’t last the winter,” Jacopetti predicted. “Wires go down. Relay towers. I doubt anybody’ll fix ’em.”

Joey went on DXing. Kindle said Joey had twice made brief contacts with other continents—a ham in Costa Rica, and on one memorable clear night a voice speaking what Joey said was Russian but might have been Polish or Ukrainian… the signal faded before he could respond.

Beth Porter, in a gesture that took Matt by surprise, had brought along a VCR and two tapes from the big video store on Ocean Avenue : White Christmas and It’s a Wonderful Life. “Because I used to watch those movies every year. You know, I just thought it would be nice.”

Joey took time away from the radio to hook up the tape machine. Kindle freshened the punch and Miriam Flett, in another surprise move, volunteered to make popcorn.

Somewhere between Bing Crosby and Jimmy Stewart, Matt thought: My God, there are only ten of us. But this might work. This might still work. This might still be a town.

* * *

Sometime after midnight, the rain turned to sleet and the roads began to ice. It’s a Wonderful Life cranked to an end, and in the silence that followed, without warning, Paul Jacopetti began to weep—racking sobs that shook his large body like seizures. Beth retrieved her videotape: “Jeez, I’m sorry, maybe that was the wrong thing to show.”

“It was fine,” Matt told her. “Don’t apologize.”

But the party was over. Kindle offered bedroll space to anyone who wanted to stay the night. Tim Belanger had confined his drinking to Diet Pepsi and offered a drive to those who hadn’t; he left with Bob Ganish and the still-teary Paul Jacopetti.

Joey was still working the transceiver. Beth told him a couple of times she wanted to go home, she was tired, the streets weren’t getting any safer. “Just wait,” Joey said, turning the dial with a relentlessness that looked nearly compulsive to Matt.

Kindle said Beth could take one of the spare rooms, if she didn’t mind sleeping on the floor, but she shook her head and pursed her lips: “I want to go home.”

“I can drop you off,” Matt said. “If it’s okay with Joey?”

Joey shrugged, his back turned. Another voice crackled from the radio speaker: “…read you, Joseph… signal’s faint.…”

“It’s that Colonel Tyler,” Kindle said. “I swear, that son of a bitch never sleeps.”

“ Tyler,” Matt said. “He’s the guy down south?”

“He moves around. Loner type.” Kindle escorted Matt to the door, out of Joey’s earshot. “You should talk to him some night when the signal’s less feeble. Joey thinks the guy is hot shit.”

“You don’t?”

“Well… it’s too soon to be choosy about the friends we make, right? But Tyler’s full of all kinds of ideas. He says we should form a defense committee or something. Says he’s seen some mayhem out on the road. A lot of peculiar people turned down Contact, he says. He keeps talking about some big project out in Colorado he’s heard about… Matt, he claims the aliens are building a spaceship out there. Is that possible?”

“I guess it’s possible. I suspended judgment last August. You don’t believe him?”

“Oh, I believe him, I guess.” Kindle rubbed his chin. “I believe him, all right. I just don’t, you know, trust him.”

“He’s in no position to do us harm.”

“Not at the moment,” Kindle said.

* * *

Beth huddled into the passenger seat. Matt asked her to fasten her seat belt. The roads were slick with sheet ice, and it was easy to imagine his little import sliding into a ditch.

Beth strapped herself in and gazed through the window at dark suburban houses.

He signalled a left turn on Marina, crossing town to Beth’s house, but she touched his arm: “No, keep going… I don’t live there anymore.”

He frowned but crossed the intersection. “Moved out from your family?”

“It never was much of a family, Dr. Wheeler. Mainly just my dad, and he’s—you know. Changed.”

“I guess it’s hard to talk to him.”

“It used to be hard. Now he wants to talk—but it’s worse, in a way. I think part of the deal is that if you want to live forever you have to understand what a shit you were in real life. He figures he kicked me around too much, and he doesn’t know what to do about it. He wants to apologize or make it better somehow.”