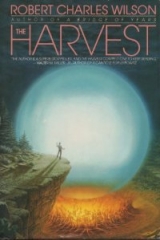

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Nothing.”

Tm not drunk.”

“No, sir.”

“Maybe you should have a drink yourself.”

“Later, sir, thanks.” Murdoch served out equal portions of canned corned beef hash. Tyler liked canned corned beef hash, but Murdoch thought it resembled dog food too closely. It was like ladling out hot Alpo. “Shitty weather, sir.” The rain had returned with a vengeance; there was occasional sheet lightning and a muted, continuous thunder.

Tyler accepted his bowl of hash and held it in his lap. “We’re nothing without a community, Mr. Murdoch.”

“No, sir.”

“A community defines the perimeters of behavior the way a border defines the perimeters of a nation.”

“Mm-hm.” Alpo or not, Murdoch was hungry tonight. He sat opposite the Colonel and gazed past him at the window. Nighttime now. Night came early these days.

Tyler was frowning. “Skins, you say.”

“Yes, sir.”

Murdoch had told the Colonel about the skins he’d found. He’d kept quiet about Soo Constantine, however. Murdoch couldn’t explain his reticence even to himself, but it seemed better that way. Soo was a new and particular discovery. His own.

“Just their vacant… their empty…”

“Skins, sir, yes.”

“Horrible.”

Murdoch nodded.

“What do you suppose happened to their insides, Mr. Murdoch?”

“I think—” Soo had told him this. Best be cautious. “It’s possible they just kind of faded. Disappeared from the inside out. Didn’t you get that hint in Contact, sir? That it would be possible to leave the body behind?”

“I never thought—not like a lizard shedding its scales, no. I wouldn’t have expected anything that repellent.” The Colonel took a halfhearted spoonful of the hash. “And the Helper?”

“Nearly assembled.”

“I would prefer not to linger in this town, Mr. Murdoch.”

“Sir, the weather—”

“You were never scared of rain before we came to Loftus.”

“It’s a cold, dirty rain. Some of these mountain roads could wash out.”

“We can deal with that.”

“Yes, sir. I’d just prefer to deal with it when it isn’t storming.” Tyler showed him a baleful look. “Something in this town attracts you?”

“Shit, no, sir.” But Murdoch felt himself begin to sweat. “Community,” Tyler said. “A human presence.”

“Sir?” Was the son of a bitch psychic?

“We need a radio for the sake of community, Mr. Murdoch. Maybe we can be more effective in numbers than we are individually. Between the two of us, frankly, there isn’t much in the way of discipline. We say the words, but it’s reflex. You don’t respect me as a superior officer.”

Murdoch was startled. “That isn’t—”

“It’s not your fault. On the road, we’re simply two men. All the structure has fallen away. I should have understood that when I talked to the President.

He was in Lafayette Park, Mr. Murdoch, with his shirt undone at the collar. The center cannot hold—isn’t that what the poet said? Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. Anarchy is without structure; it flows like water. Mr. Murdoch, do you suppose we’ve lost structure entirely? Has it gone that far?”

“I—wouldn’t know.”

“If there were more of us,” Tyler said.

“Yes, sir.”

“It’s as if we left our own skins behind. Our skins of propriety. Our skins of good conduct. Suddenly we’re raw; our nerves are exposed. We’re naked. With the right provocation, we could say or do anything.”

“Yes, sir,” Murdoch said, realizing as he spoke that his friendship with Colonel Tyler had also peeled away; that the skin of amicability had been shed in this room and the thing beneath exposed: a queasy mutual fear.

* * *

After dinner, he left the Colonel and hurried into the dark street. He was meeting Soo at the Roxy, and he was already late, according to the digital watch on his wrist. Since Contact, Murdoch had kept two watches, one on his wrist, one in his pocket, so when he replaced the battery in one watch he could set it by the other.

The Roxy was easy to find. It was one more peeling Main Street movie theater, its blank marquee shedding rainwater in cold sheets. Murdoch hurried past the empty ticket box, inside to the lobby where Soo had turned on the lights.

She was waiting for him, still wearing her yellow T-shirt, one hand cocked on her hip, standing in the doorway of the auditorium. Murdoch looked at her and felt weak all over.

Probably it was only the effect of a long separation from female company. What it felt like was high-octane, knee-buckling, adolescent lust. She was a compact package of curves and smiles and he wanted to pick her up in his arms and feel her weight. Soo, he thought. Some kind of weird southern name for a young girl. He said it twice to himself. Lord, Murdoch thought, take pity on a soldier.

“You shaved,” she said.

He nodded, blushing.

“There’s no more candy at the popcorn stand,” she said. “But I got some Cokes in a cooler. The movie’s ready to go. It’s 42nd Street.We can watch it from the projection room. Come on, A.W.!”

Speechless, he followed her upstairs.

* * *

Between reels she talked about herself; while Murdoch, listening, writhed in a fever of hormonal suspense.

He watched the words come out of her mouth—the way her lips moved when she talked.

“I wasn’t born here. I was born in a town two counties east. Town of Tucum Wash, if you call it a town, really a gas station and a post office. They bused us thirty-five miles to school every day. Well, I hated that place. It’s a common story, I guess. Everybody hates their hometown—especially if they come from a little wide-place-in-the-road like Tucum Wash. So when I graduated high school I came here looking for work. To Loftus, yeah, I see you smiling. Bright lights, big city, right? I guess you must have seen all kinds of places. But I’ll tell you, A.W., I never wanted much more than Loftus. Loftus isn’t bad. I worked at the K mart checkout and two nights a week at the Sandwich Castle in the mall. It’s actually an okay kind of life. I kept myself in TV dinners and I had some fun. Had a boyfriend. Dean Earl was his name. Oh, he’s gone—you don’t have to look so long in the face. Dean didn’t mean that much to me. Except every Friday night or sometimes Saturday we’d come here to the Roxy. I love movies. I won’t watch ’em on video. Like watching a postage stamp. Plus it don’t smell right. You know what I mean? You ever smell a theater? People think, oh, popcorn, but it isn’t the popcorn. In summer it’s that air-conditioning down the back of your neck, smells like cold metal, and the smell of sweaty people comin’ in with their jackets over their shoulders and mopping their faces with handkerchiefs, waitin’ for that chill to shiver up their spine. And when everybody’s cool, the lights go off and the movie starts. Course I can’t make it be like that. But when folks started leaving, you know, leaving, I couldn’t help but think of the Roxy and how nice it would be to come here all by myself. And I did. Maybe you think I’m crazy. But it’s nice here. It’s not the same, but it reminds me of the old days. Well, maybe I am crazy. A.W., let me work this machine! Your hands are cold. You’re still wet from the rain, aren’t you? Shivering like a pup. You want dry clothes? You know, I thought you might get wet. I picked up some clothes at the K mart after we met this morning. Clothes about your size. Bet that A.W. comes out in the rain, I thought. He looks like he’d come out in the rain. Take that shirt off. Your shirt! Well—mine, too, if you like.”

* * *

Later, Murdoch felt obliged to tell her about himself.

They shared a mattress on the floor of what used to be the office of the manager of the Roxy Theater. She was naked in the faint light, sitting cross-legged in a curl of woolen blankets. Murdoch was full of quiet wonder at the sight of her. Five minutes ago, they’d been joined in a passion so intense that Murdoch thought they might penetrate each other’s skins, occupy each other’s space. Now she was sitting apart from him, a little aloof, but smiling, in a blur of light from a high window where the rain washed the dusty glass. It was after midnight by the watch on Murdoch’s wrist. He felt a need to justify himself.

So he told her about growing up in Ukiah, leaving home, enlisting, discovering his aptitude for machines. How he had learned the tolerances and mannerisms of small arms, their maintenance and renewal, their weaknesses and strengths. A weapon was a complex environment in which a small event—the squeezing of a trigger, say—led to vastly larger consequences: the discharge of a bullet, the death of a man, the winning or the losing of a war. But only if everything was in balance; only if the weapon was correctly toleranced, unworn, clean and dry here, oiled there. It captured his imagination. In a world Murdoch often found confusing, here was a map he knew how to read.

Soo listened attentively but began to frown, and he hurried to change the subject: “Then came Contact, you know, and then I met Colonel Tyler and we started this little cross-country turkey shoot.”

“ Turkey shoot?”

“Well, you saw the Helper—what happened to it.”

“Uh-huh. Big mess, frankly. Took out the window at the five-and-dime and the rain came in and mint the magazine rack. You guys do that a lot?”

He wasn’t sure whether he ought to boast or confess. “Maybe twenty times, twenty different towns since October.”

“Isn’t it dangerous?”

“The Helpers don’t fight back.” They don’t have to, Murdoch thought. “I mean, dangerous for regular people. Like civilians.”

“We haven’t killed anybody so far.”

She nibbled her thumb. “I don’t want to hurt your feelings, A.W., but it seems kind of pointless. Like, the Helpers almost back together again.”

“We only just found out they can do that. But is it sensible, you mean? Soo, I don’t know. Colonel Tyler thinks so.”

The taste of her skin, her lips, was still in his mouth. Murdoch thought: We smell like each other.

“Going to do it some more?”

“The TOW shoots?” He shrugged. “Maybe I won’t. Colonel Tyler… I can’t speak for him. Sometimes I think…”

“What?”

“He’s maybe not the world’s most stable individual.”

“You didn’t look that stable yourself, this morning.” Her smile was mischievous.

He shook his head at the memory. “Well, Christ… skins!”

“Come on… it’s not so terrible.”

He looked at her sidelong. “You said those people, what, faded away?”

“Kind of. You know, A.W., it was something they decided to do. It’s how they wanted it. Maybe in some other town more people stayed in their flesh. Around here—I guess it sounds stupid, but there isn’t that much to do. You remember Contact? Travellers said in time people might not want the flesh? Well, that’s all this is. Mrs. Corvallis, she used to run the hair salon, she rented me a basement room—I watched her go. We were friends. I sat with her a lot. Toward the end she was just—I don’t know how to describe it—very pale. You could tell she was going. She was like china. Like porcelain. Almost shiny, light as a bag of feathers. The Travellers were holding her together until the end. A.W., you know what they call neocytes?”

He nodded. He’d heard the word from a medic at Quantico, shortly after Contact.

“Well, the neocytes kept her together. Until she was living mainly on the other side, hardly here at all. Then one morning I knocked on her door and nobody answered and when I went in her skin was there, all empty. It wasn’t so bad. She was happy about it.”

But Murdoch couldn’t suppress a shudder. “It was her choice—you honestly think so?”

“I know it.”

“Horrible,” Murdoch said.

“A.W., what’s the alternative? When you die, you know, you leave your skin behind, too… and considerably more than that. It gets buried in the ground and rots. This was cleaner—and it wasn’t death.” She was still smiling, but gently, almost absently. “What was Contact like for you?”

“Same as for everybody,” he murmured—softly, because a terrible suspicion had touched him and lingered a moment before he could dismiss it.

“No,” she said, “for you. I really want to know.”

“The Travellers came that night in August and they made an offer. What else is there to say?”

“You turned them down.”

“Obviously.”

“Any particular reason?”

“I think—no, it’s stupid.”

She focused her large eyes on him. “Tell me, A.W.”

“When we moved from L. A. up to Mendocino County, I used to follow my father around those woods. Big Pacific woods. I was nine or ten years old and it scared the shit out of me—redwoods, helicopters, but not just that: it was the bigness of everything. I got lost once. Only for maybe half an hour. I sat under a tree until my old man found me. But I couldn’t help thinking about the woods rolling on for miles all the way to the sea, the sea big enough to cover up every place I’d ever lived and everyone I knew, and a sky big enough to drown the sea—shit. Does this make any sense?”

Soo nodded gravely.

Murdoch was embarrassed, but he went on talking almost in spite of himself. “I don’t think I trusted anything after that unless I could hold it in my hand or take it apart. Contact sounded real good, you know, in its own way. I’m not ashamed to admit that. But it was like being out in those woods again. Everything was so—” There wasn’t a word for this feeling. “Big.”

“So you said no.”

Murdoch nodded.

“A.W.—did you ever regret it?”

“You mean, would I do it the same way over again? I don’t know.” He thought of the skins. “It still scares the shit out of me, frankly.”

“Maybe if there was somebody with you.”

He looked at Soo a long time in the dim light. “But that’s not possible.”

“I think it might be.”

“They said—the Travellers said—Soo, the neocytes aren’t inside me anymore.”

“A.W., if you want a second chance, I think it could be arranged.”

He backed away across the sheets. “How would you know that? I mean, how would you know?”

She looked deeply worried. “Is it possible to fall in love with someone in less than a day? It wouldn’t surprise me. Because I think I did. Stupid me.” She sighed. “No, they aren’t inside you. But they can be if you want them. It would be as easy as a touch, A.W. A kiss. If you want them. It’s not too late.”

Murdoch couldn’t think clearly. He grabbed his pants and pulled them on, backed against a wall and stared at her. He summoned words and the words spilled out: “I thought you were human!”

“Oh, God. I am! I just wanted to stay this way a while longer. It’s a choice, A.W., it really is. I like my skin. There’s skin in the new life, too, I mean it’s not just angels floatin’ around heaven, but… I wanted to have my Earth skin and be in Loftus a while longer.” She hung her head. She looked weirdly penitent, like a little girl caught stealing cookies. “I should have told you!”

He thought of what he’d seen this morning, dry parchment in the shape of an arm, a hand, fingertips. He looked at Soo. This skin he’d just touched. He imagined it empty and dropping like isinglass, perhaps blowing down the street in a strong wind.

God help me, Murdoch thought, I held her in my arms! And all along…

… all along, she had been one of them…

… one of them, under her skin…

“A.W.,” she said, “please don’t leave. Please! I’ll explain.”

The monster wanted to explain.

Murdoch shook his head and ran for the door. He left most of his uniform behind. He didn’t want his uniform. There were other clothes. He wanted this cold rain to wash him. He wanted it to wash him clean.

* * *

John Tyler placed his service revolver on the desk opposite the bed where he could see it. He was reassured by the sight of the weapon. It was substantial and weighty. It was like an investment, Tyler thought, something withheld until its value increased.

He was thinking about loyalty.

Loyalty was the fundamental thing, Tyler thought. Loyalty was normalcy reduced to its essentials. Loyalty allowed no room to maneuver. Loyalty was precise.

He had begun to entertain doubts about Murdoch’s loyalty.

Tyler was sitting at the rainswept window watching the dark main street of Loftus when Murdoch came stumbling back to the hotel.

Murdoch was a ludicrous sight, naked above the waist and barefoot, mincing over patches of broken glass in the midnight rain.

It might have been funny, except for its implications about what Murdoch had said and refrained from saying… implications about this town and about Murdoch’s loyalty to Tyler.

He listened through the wall as Murdoch let himself into the adjoining room. There wasn’t much to hear. The shower ran for a long time before the room grew quiet again.

Tyler eased back into his chair.

He had been without sleep for two days, and he hadn’t left this room since Murdoch took him down to see the Helper rebuilding itself. This was his madness come back again, Tyler recognized, but he had forgotten that madness was also clarity; madness was the ability to see things as they really were, to make decisions he might not otherwise be capable of making.

He could even admit that this might be a form of Sissy’s madness, a madness he had inherited. Sissy had heard voices. Tonight Tyler heard a crowded confusion of voices hovering on the edge of intelligibility; and if he listened closely he thought the sound might resolve into words, the same words, perhaps, that had frightened and exalted his mother. But Tyler wasn’t interested in voices. They were what the doctors called an epiphenomenon, a secondary symptom, like the curious sterility of the yellow light radiating from the room’s electric bulbs, or the sour odor of stale tobacco smoke that had begun to seep from every surface. Perhaps Sissy could be deceived by such trivia; Tyler was different.

What interested him was the clarity, the speed of his thoughts. He was able to see the threads of significance that bound one event to another in a complex web of meaning.

It was both hideous and quite beautiful.

Colonel Tyler examined it, turned it this way and that in his mind, this glittering web, as the hours marched toward daylight. The rain had been falling now for forty-eight hours.

* * *

Murdoch knocked on his door early the next morning.

Tyler rose and walked to the door and opened it just as Murdoch was preparing to knock a second time.

“Sir,” Murdoch said, “I’ve reconsidered, and I think you were right. I think we should pull out of this town.”

Tyler surveyed the younger man. “You look shitty, Mr. Murdoch. You look like you haven’t slept.”

Murdoch blinked. “No offense, sir, but you’re no bed of roses yourself.”

“It’s still raining,” Tyler said, savoring this.

“Sir, yes it is, but—”

“You made a convincing case about navigating these mountain roads in the rain.”

“Well, as you yourself said, sir, we shouldn’t be scared by a little rain. I think—”

“No. You were eloquent on the subject. We have to be careful. We can’t phone 911 if we slide off a mountainside. It’s a new world, Mr. Murdoch.”

“Yes, sir, ” Murdoch said miserably. “But—”

“We can afford to stay another day.”

Murdoch seemed to surrender; he bowed his head. “Yes, sir.”

“Or longer.”

“Sir?”

“Depending on the weather.”

* * *

Tyler was buoyed by this small victory, and in the afternoon he felt well enough to brave the rain. He ducked across the street to a clothing store, found a yellow rain slicker, and wore it for protection as he explored the immediate neighborhood of the hotel.

The town was small and might not contain what he was looking for… but then again, it might.

He stalked the rain-washed streets of Loftus with his gaze aimed at each shingled roof he passed. He was scouting for an antenna.

Some of these houses were equipped with ancient rooftop television antennas; some had satellite dishes mounted on their lawns like enormous mushrooms. Most, Tyler presumed, were wired for cable. But it wasn’t a TV antenna he was hunting for. Tyler walked on, a strange figure in his yellow raincoat, the only color and motion in these gray and empty streets.

By five o’clock, the light had nearly failed. Tyler was preparing to turn back when he looked east on one of these narrow residential streets and saw a tower silhouetted against the blue-black sky—a radio tower with a beam antenna mounted on it.

Smiling to himself, Tyler hurried down the block to the pertinent house and kicked open the front door. The lights blazed on at the touch of a switch. It was amazing, he thought, and maybe it was more than amazing, that the power hadn’t failed. In every one of these whistlestop towns they’d passed through, the wall plates continued to offer 120 volts of AC as reliably as ever—maybe more reliably. It was a mystery… but Tyler set it it aside for later pondering.

Inside the house, he found two of the skins Murdoch had talked about. He regarded these relics with a faint distaste, probing them with his shoe. The skins were dry and snaky and he understood Murdoch’s alarm.

But they were harmless dead things, too, and Tyler was able to ignore them.

In the basement he found what he’d been looking for: a small room decorated with QSO cards and antique code keys, and on a knotty pine desk, a Kenwood radio transceiver of recent vintage.

Tyler switched on the machine to make sure it worked. The faceplate lit up; static whispered from the speaker.

Who might be out there? Out there even now, Tyler thought, voices buried in this whisper of noise.

Maybe no one, Tyler thought. Or maybe a population of survivors. One in ten thousand Americans was still a large group of people. Such a population would know nothing about him. None of them would know about Stuttgart or any other of his long nights; none of them would know he had held a gun on the President. Among such people, he would have essentially no past. He could be a new thing; he could be what he looked like in a mirror.

He tuned the radio with scrupulous care. He was disappointed by its silence, but he persisted for hours, until long after dark, until he heard the faint sound of Joey Commoner talking to Boston, Massachusetts.

* * *

When Tyler analyzed the events that followed, his verdict was: I shouldn’t have played with the pistol. It was the pistol that made things go bad.

When he came back to the hotel he found Murdoch frying hamburgers on the hot plate. Tyler wasn’t hungry; his headache had gotten worse. After dinner, Murdoch hauled a case of beer into the room. Tyler matched him bottle for bottle. It was a stupid thing to do, under the circumstances. The alcohol affected his judgment.

He talked long and volubly and perhaps not too coherently about the large things on his mind: about loyalty and sanity. “In the end,” he told Murdoch, “it comes down to obedience. Obedience and sanity are the same word—wouldn’t you agree, Mr. Murdoch?”

Murdoch—who had been nervous to begin with and seemed no better for his massive intake of Coors—looked at Tyler wearily. “Tell the truth, sir, I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

“That’s a hell of an admission.”

“Is it? What’s that supposed to mean?” Now Murdoch was angry. “It’s an insult, right? Jesus. I swear I don’t understand you. Half the time you come on like a good old Army boy, half the time you sound like some faggot college professor. I don’t even know why we do this military routine. Aye sir, Colonel sir. Just because you’re walking around like you have a ramrod up your ass. Salute me, I’m wonderful. Well, fuck it. It’s not just stupid, John, it’s not even sane.”

Tyler was stung by the extremity of this.

“Epictetus,” he said.

Murdoch, exasperated: “What?”

“The Discourses. ‘Why, then, do you walk as if you had swallowed a ramrod?’ Epictetus. He was a Stoic. An educated Roman slave. You shouldn’t insult me, Mr. Murdoch.”

“All I meant—”

But Tyler’s attention had strayed to the pistol on the side table. Spontaneously, in a motion that seemed to belong to his hands alone, he picked the weapon up.

Murdoch’s eyes widened.

It was an old-fashioned revolver. Tyler opened it to show Murdoch the chamber. “Empty,” he said. Then he took a single bullet from the tabletop, displayed it between his right thumb and forefinger, and placed it in the pistol.

Or pretended to. In fact, he palmed the bullet… but Murdoch didn’t see.

“One round,” Tyler said.

He spun the chamber without looking at it.

He raised the pistol to his own head. The act was familiar, but he had never performed it in the presence of another man. It made him feel strange, dizzy, not altogether connected to Murdoch or this room or the exterior world in general.

He looked steadily at Murdoch as he pulled the trigger. Click!

He spun the chamber again.

“That’s the advantage I have over you, you lame little fuck. That I’m capable of this.”

Perhaps Murdoch, the weapons specialist, was visualizing the internal working of the pistol, the firing pin as it came down on empty air—or not. Click!

“I can do this without flinching. Now. Can you?”

Murdoch huddled away from the barrel of the pistol. He looked pinned in his chair by an invisible wind. His Adam’s apple bobbed in his throat, a motion Tyler watched with fascination. It looked like there was something inside him trying to get out, something more substantial than a word.

“Christ,” Murdoch said in a strangled voice, “please, Christ Jesus, don’t!”

“This is why you call me sir. You understand?”

“Yes! Yes, sir!”

“I doubt it.” Click!

“Christ, Christ, put the gun away, Jesus, don’t do this to me!” Murdoch was rigid with terror. His hands were clamped on the arms of the chair. In the sterile light of the hotel room, Murdoch’s wristwatch was clearly visible. Tyler watched the numerals blink. He counted thirty seconds, then he lowered the pistol.

He looked at Murdoch and smiled. “We’ll leave in the morning,” he said.

Murdoch opened his mouth but no sound came out.

Tyler put the pistol back on the table. “Maybe you should get your things together, Mr. Murdoch.”

Murdoch blinked until he realized he had been excused, the ordeal was over. Then he stood up on shaky legs, walked to the door, turned, and took a last bewildered look at Tyler before he left and closed the door behind him.

Tyler’s headache was much worse.

Later, it occurred to him to look for the bullet he’d palmed; but it wasn’t beside the chair, nor in his pocket, nor on the tabletop. Finally he opened the pistol and found the bullet resting in the chamber—exactly where he had led Murdoch to believe it was. Which worried him a little. It was a strange sort of mistake to have made.

* * *

Murdoch lay awake for what remained of the night with the door of his hotel room locked and chained—eyes open, because when he closed them he saw the barrel of Tyler’s service revolver pointed at him.

Or Soo Constantine, pale and naked in a darkened room.

Or an empty human skin littering the doorway of an old house.

Dear God, he thought, what if Tyler had shot him? He wouldn’t be a skin. He’d be a corpse. A messier object, as Soo had pointed out.

She’d talked about the missing people as if they had really gone somewhere. Had they? True, the Travellers had promised that. The memory of Contact was vague in Murdoch’s mind, a dream that paled by daylight. But he remembered the promise of a new kind of life, both physical and bodiless… an idea that had made sense, somehow, in the intensity of Contact.

It’s not too late, Soo had said.

And why did the words linger on?

Was he actually tempted by the offer? Was such a thing possible? But that’s terrible, Murdoch thought: I don’t want to be an empty skin on some empty street, like a bottle somebody drained and threw away. It’s something they choose. No. Bullshit, Murdoch thought. But she hadn’t seemed like a liar.

He tried to imagine himself travelling on with Tyler, watching the old man sink into outright lunacy, firing missiles at something, anything—trying to make sense of the world by dismantling it.

Christ, Murdoch thought miserably, I don’t even know where I am! I couldn’t find this town on a map. Loftus? Where is it?

I’m lost, Murdoch thought.

Rain tapped on the window.

He tossed and slept a little in the last hour before dawn.

* * *

Tyler woke regretting the incident of the night before and tried to act as if it hadn’t happened. He knocked on Murdoch’s door and asked for some help loading up the Hummer. Murdoch nodded—both of them a little sheepish, Tyler thought, in the sober light of morning—and began to assemble the cooking gear.

They carried their personal items to the street, around the corner to the Exxon station where the Hummer was parked under cover. Tyler arranged the baggage in the rear of the vehicle and made sure everything was strapped down. Murdoch, looking baleful and confused, watched from a few feet away.

Then Tyler took the passenger seat and waited for Murdoch to climb in behind the wheel. It was a conciliatory gesture, giving Murdoch the reins, a small apology for the night before.

But Murdoch didn’t move. “Sir,” he said, “I think I left something in the room.”

Tyler took a pair of sunglasses from his breast pocket and polished them on a handkerchief. “What sort of thing, Sergeant?”

“Compass,” Murdoch mumbled.

“Isn’t that with the mess kit? I thought I saw it there.”

“Sir, I don’t think so.” He made no move to look.

The air in the garage was thick. It smelled of gasoline and old solvents. This is a dark place, Tyler thought, an oppressive place.

“It was a cheap compass,” he said. “We can find one like it anywhere.”

“It’s easier if I just go back, sir.”

“Back to the hotel room?”

“Yes, sir.”

Tyler understood the lie and the significance of the lie. It made him feel enormously sad—this shabby little betrayal.

“Well,” Tyler said. “You’d better hurry, then, Sergeant.” Embarrassingly, Murdoch couldn’t hide his relief. “Yes, sir.”

“I’ll be waiting.”

“Yes, sir.”

Colonel Tyler watched his young blond-haired friend leave the Exxon garage. Murdoch was haloed for a moment in the morning light—the rain had finally stopped—then he turned into the shadow of a taller building and was gone.

* * *

Soo was in the manager’s office of the Roxy, only just awake, wearing a gray sweatshirt that reached nearly to her knees. She looked up as Murdoch came through the door.

The room was different in the morning light, Murdoch thought. Sunlight came through the small, high window. The floorboards were lustrous and ancient. The mattress looked disheveled, as if the girl hadn’t slept much herself.