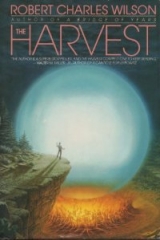

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

At the apex of the drive, where the road began a descent into the hospital district, the battering rain suddenly eased. Matt spared a glance to the west. The clouds, skimming overhead at a dizzying speed, had briefly lifted. He could see the water of the bay driven up beyond the marina and nearly to Commercial Street, the hulls of overturned pleasure boats bobbing level with the roofs of warehouses and restaurants. The bay itself was a furious caldron, though calmer than the sea beyond, where waves the size of houses battered the stony southern tip of Crab Pot Island. The last daylight came from the west—seemed to come from the storm itself, a strange, weak radiance.

He turned his attention back to the road and swerved to avoid a cartwheeling tree limb. The wind made his steering awkward; it was like driving into a tide of molasses.

“Dear God,” Miriam said suddenly. “Look at that.”

And he looked again, reluctantly, toward the west.

Offshore, the racing overcast had begun to dimple.

Black clouds grew lazy tails, which spiraled toward the sea.

Where they touched, white foam erupted.

Waterspouts, Matt thought. He counted five of them. It was fascinating, almost hypnotic, how they moved. There was something awful about their twisting, like the lash of a cat’s tail, plucking the water here and there, then lifting and falling again. Moving in the dim light. Moving toward shore.

A sudden curtain of rain obscured the view.

“Maybe you had better drive a little more quickly,” Miriam said.

* * *

Everything would have been all right, Abby Cushman thought, except for the ventilator ducts.

The storm was way too big, and coming way too fast, and Matt Wheeler was still out there somewhere, hadn’t even arrived at Miriam Flett’s house when the phones went dead… and then the lights in the basement cafeteria began to dim, and Tom Kindle ambled away to some other corner of the building to start up a generator, leaving Abby alone with six more or less terrified people in the flickering dark… and all this would have been endurable, except for what she had begun to think of as the God Damn Noise.

She had no idea how the hospital was ventilated. She knew only that several pressed-tin ducts ran along the ceiling above the fluorescent fixtures, and that the wind had somehow penetrated these conduits. Worse, the wind had begun to play them like a pipe organ. Not any ordinary pipe organ, Abby thought, but a pipe organ for mastodons and great whales; a pipe organ that produced sounds too fundamental for the human ear, perceptible only, like fear, in the hollow of the stomach.

The God Damn Noise had begun a little after six o’clock. It was innocuous at first, almost a whisper; then above that, as the velocity of the wind increased, came an intermittent keening note—eerie, but bearable.

Then the whisper rose to shouting volume, the sound of a bathroom shower running full tilt. And other noises began to creep in along the columns of hammered tin, in particular a low wail that made Abby think, uncomfortably, of a crying child; and periodic creaks and pops, as of sheet metal stressed beyond its tolerance.

She endured that… though it made her feel absurd, serving Oreos and lukewarm coffee to six individuals huddled knees-to-chest on hospital mattresses on a cold linoleum floor. Pollyanna in a pantsuit. She felt like a jennyass, frankly.

But then Bob Ganish began to complain of claustrophobia: It was too close in here, he insisted, especially with the fluorescents out and the damn battery lanterns casting such a dreadful low light—seemed like the air had gone bad. So Abby had to sit with him and share her cookies and change the subject. Hey, what was the best sale he ever made down there at Highway Five Ford? The drop-dead pinnacle of his sales career? And Bob smiled nervously and launched into a description of the near-criminal flogging of a used 1990 Pinto. The monologue lasted twenty minutes, by Abby’s watch, including details on the financing. All the while the ducts screaming and Abby beginning to feel that Ganish’s hysteria, by some reverse osmosis, was draining into her.

Okay, all that, and Dr. Wheeler still out in the storm…

But then the wind made a sound that was, in Abby’s imagination, precisely the sound the last T. Rex might have made, dying in a pool of hot Cretaceous mud…

(—her grandson Cory had been a dinosaur buff—)

…and to top it all off, that was the moment Paul Jacopetti picked to have his goddamn heart attack.

* * *

Abby was startled by the sudden commotion of voices. She turned away from Bob Ganish, spilling her coffee onto his pant leg. (“Ouch, Abby, hey!”)

Jacopetti lay face-up on his mattress, his hands clutched over his chest. His face was pale, and he was breathing rapidly, wheezing.

Worse, everyone seemed to expect Abby to do something about it.

She hurried to Jacopetti’s mattress and crouched over him. “Paul? What is it?”

“I’m having a fucking heart attack,” he gasped, “what does it look like!”

Her first impulse—she was instantly ashamed of it—was to slap him. Tell him: Not now! This isn’t the time or the place, you idiot. Have your heart attack later.

Instead she asked, not too intelligently, “Does your chest hurt?”

“Yes, it hurts. Hurts like a son of a bitch.” He closed his eyes and grimaced.

Abby looked up. Everyone had gathered in a circle around the mattress, their attention on Jacopetti, or worse, on her. The ventilator ducts screamed. Abby heard the sound of a window breaking, perhaps up on the second floor, a nerve-wrenching sound conducted directly into her eardrums.

She said, half to herself, “I don’t know what to do.” Then, as the last buckles of restraint broke loose, louder: “I don’t know what to do! Stop staring at me!”

She felt a hand on her shoulder, gently pulling her aside—Beth Porter’s hand.

Abby bit her lip but retreated from the mattress. Dazed, she watched Beth kneeling over Paul Jacopetti. “Mr. Jacopetti?” Beth said. “Mr. Jacopetti, can you hear me?” He opened his eyes. “You… what do you want?”

“Mr. Jacopetti, you have to tell me what’s wrong.” Perhaps the pain had gotten worse—Jacopetti seemed suddenly more malleable. “Chest hurts.”

“Show me where,” Beth said.

Jacopetti raised his right hand and drew a circle on his shirt above the breastbone.

“There in the center?” Nod.

“How about your arm? Does your arm hurt at all?”

“No.”

“How about your breathing?”

“Tight.”

Gendy, Beth levered back the man’s head so his chin jutted up. “Mr. Jacopetti, I know this is a personal question, but are those false teeth?”

“Dentures,” he managed. “Why?”

“Can you take them out? In case you fall asleep or anything. It’s safer. Or I can take them out for you.”

Jacopetti pried out his teeth. Abby had always been a little frightened of this man—his barrel-shaped body, his booming voice, his invincible cynicism. But Jacopetti without his teeth looked altogether less threatening. His cheeks seemed to collapse inward, giving him an old man’s gummy frown.

Jacopetti looked up at his audience. “Thuck you,” he said/Thuck all oth you.”

“We could use some more light,” Beth said hurriedly. “Maybe if everybody would just sit back down?”

They did, though Abby stayed close, mad at herself for failing this test. If it hadn’t been for the noise…

“Mr. Jacopetti,” Beth said, “are you nauseated?”

Nod.

“Feel like you might throw up?”

“Maybe.”

“Could somebody fetch a towel just in case?” Chuck Makepeace dashed for the bathroom.

“Mr. Jacopetti, listen to me… Did you ever have this pain before?”

“Not as bad.”

“But you’ve had it before?” Nod.

“Seen a doctor about it?”

“No.”

“It always went away?” Nod.

“Okay,” Beth said. “That’s good. I think what you have isn’t a bad heart attack. I think it’s angina. It’ll probably pass if you lie still.”

Joey Commoner, leaning against the wall with a strained expression, said: “How would you know?”

“Hush,” Abby told him, and got a sullen glare in exchange.

Bob Ganish, his claustrophobia forgotten—misplaced along with his common sense, Abby thought—offered: “This man should be in a hospital.”

Jacopetti: “I am in a hothpital, you athholel”

Ganish reddened. “I mean, he needs proper medical attention.”

Abby took the salesman aside a second time. “I know he does, Bob, but our proper medical attention seems to be lost in the storm. Let’s sit down, shall we?” She looked at her watch. Seven-forty-five. How much worse could this weather get? Much worse, she supposed. The eye, the Helper had told her, would probably pass directly over Buchanan, possibly around midnight. And that was only half the storm.

“I wish,” she muttered, “somebody would turn off this goddamned noise.”

* * *

Matt felt as if he had fallen into some peculiar time warp: The smaller the distance between himself and his destination, the more slowly he was forced to proceed.

The enemy wasn’t so much wind—though that was bad enough—nor even Miriam Flett’s relentless backseat driving. The enemy was visibility. More precisely, invisibility.

All traces of daylight had passed. The rain was continuous and dense as fog. It carried with it tiny particles of salt and something else, a crystalline dust, some sort of sea life, Matt presumed. The effect of this was to obscure his vision so completely that he turned onto Campbell Road, the direct route to the hospital, without any certainty that he had chosen the right intersection. There were no landmarks, nothing perceptible beyond five or six feet from the car even in the high beams. He drove hugging the right side of the road, scanning for the sign that marked the entrance to the hospital, then worrying that he’d passed it—maybe it was set too far back from the tarmac.

A particularly strong wind rocked the car up on its right-hand wheels; Miriam sucked in her breath. “I should have stayed home!”

“Home might be underwater by now,” Matt said. “Try not to worry, Miriam. We don’t have far to go, and we’ll be safe at the hospital.”

“Can you guarantee that?”

“Stake my life on it.”

“Not funny, Dr. Wheeler.”

“Not meant to be.” Desperate, he took the next available right. It looked like the entrance to the hospital—the shrub on the corner seemed familiar.

But it wasn’t the hospital. He identified, on close approach, an unfamiliar yellow speed bump, a parking lot that curved the wrong way; finally, the broken window of the local 7-Eleven.

Miriam’s hands were clenched together in her lap, arthritic knuckles knotted together. She said, “Are we stopping for snacks?”

It wasn’t the hospital, but it was at least a landmark. Matt tried to recall the relationship of the 7-Eleven to Buchanan General. He’d driven this route at least twice a week for years, but when he tried to map it in his head… was the 7-Eleven before the hospital? Certainly. Close to it? He thought so. But how many yards exactly? Was there another store en route, possibly a camera store? He seldom stopped at any of these shops; they were vague in his mind.

He navigated turtle-fashion back to Campbell Road and crawled onward.

Miriam gasped as a yard-long tree limb came whirling out of the darkness and struck the rear left window. The glass starred but didn’t shatter. Miriam whispered something inaudible. Matt clenched his teeth and drove.

He slowed where the curb yielded to a driveway on the right. He exchanged a glance with Miriam, then turned the wheel. This might be the hospital. It probably was. Better be.

The access lane seemed to crawl on forever in front of the car. Matt began to entertain the possibility that he had driven from the 7-Eleven into a horizonless limbo of rain and wind, all landmarks erased. He fought the temptation to check his watch every thirty seconds, try to calculate his progress. He was suddenly aware of the pungent smell of the sealed automobile, his own sweat mingled with the lighter, sourer odor of Miriam and the reek of wet upholstery and wet clothing.

He was grateful when a brick wall loomed up in the twin circles of his headlights—even more grateful when he recognized it as the east wall of Buchanan General.

He pulled abreast of the Emergency entrance. “Thank God,” Miriam said.

Matt switched off the engine but left the lights on. “I’ll come around to your side. Wait for me. We’ll go in together.” He didn’t say it, but he was afraid Miriam was light enough that the wind might simply sweep her away.

She nodded.

The door was wrenched out of his hand as soon as he opened it. The wind, Matt thought, had made everything dangerous, even an ordinary act like opening a car door. The door banged against its stops and bounced back, whacking his hip. Matt stepped aside and pushed it closed, sparing Miriam more than a momentary blast of salty rain.

He fumbled around the hood of the car with his hands braced against the cold metal. The wind was nearly strong enough to lift him up—certainly strong enough to knock his feet out from under him if he took a miscalculated step. The combination of wind and rain was blinding. With his eyes pressed tight in the darkness, every surface of his body awash, it was as if the world had been reduced to some few essential elements: the wind, the automobile, the wet concrete under his feet. Variables in a complex equation.

He groped along Miriam’s side of the car until he found the door handle. Then he steadied himself, took as deep a breath as the wind allowed, and opened the door. Instantly, the door kited into its stops; but this time Matt was ready for it; he wedged his body against the door frame and held it fully open.

He held out his hand to Miriam, but she drew away.

Matt leaned into the meager shelter of the car, where he could see Miriam—blurrily—in the faint illumination of the map light. “What’s wrong?”

She hissed back: “My journals!”

Christ in a red wagon, Matt thought.

“Dr. Wheeler! You can leave what’s in the trunk! But I want my journals!”

The journals were bundled at her feet, still wrapped in her yellow raincoat. Matt leaned over her, conscious of the wet woolen odor of her skirt—it smelled like a wet dog. He tied the arms of the raincoat together to make a sort of bag for the journals, a tedious process that left him plenty of time to reflect on the absurdity of his position, standing ass to the wind in the midst of the most powerful typhoon to approach the Oregon coast since the ice age. The rain was sluicing into the car now, soaking Miriam, but Matt had ceased to care: Let her get wet, she deserved to get wet. He couldn’t shake the memory of those funnel clouds snakedancing toward shore; couldn’t shake a suspicion that one of them might reach down and fold him into the dark wing of the sky.

When the journals were bundled together, he stood and offered Miriam his right hand. This time she took it, moaning as she stepped out of the car. As soon as she was standing he put his right arm around her waist and tugged her, half-lifted her, in the direction of the Emergency door. Only these few steps, Matt told himself. One two three.

But the hospital door resisted when he tried to pull it open. The wind? No—not just the wind.

He banged a fist against it. The door was quarter-inch-thick wire-mesh glass. Inside there was a dim light, perhaps motion… but he couldn’t see much through the blur of rain.

Feeling panic like a third presence, something large perhaps just over his shoulder, Matt pulled the wide handle of the door a third time… and this time it opened outward.

He hurried Miriam inside. She stumbled a few steps, then righted herself and took the package of journals from Matt. “Thank you,” she said breathlessly, not looking at him, brushing water from the raincoat bundle. “That was… harrowing.”

Tom Kindle pulled the door closed behind them.

Kindle held a hammer in his hand. A sheet of plywood and two pine planks were leaning against one wall.

Matt sat down on the tiled floor, panting. Water ran off him in all directions. He looked at Kindle. “You were about to board up that door.”

“Yup.”

“You couldn’t have waited?”

“It didn’t seem wise.”

“Kind of a vote of confidence, isn’t it?”

Kindle smiled. “Welcome back anyway.”

* * *

Abby Cushman met him where the stairs opened into the hospital basement. She briefed him on Paul Jacopetti’s medical crisis and added, “He’s resting easier now, though the pain hasn’t entirely gone away.”

“I’ll look at him. But I need to change into dry clothes first. Do me a favor—make sure Miriam gets dried off, too. Maybe you can find some fresh clothes to fit her.”

“All right.” But Abby hesitated. “Matt—I should tell you, I nearly fell apart when Paul got sick. It was a little embarrassing. Well—more than a little.”

“Abby, you’ve done fine. Without you, we wouldn’t all be here. You can’t handle every crisis that comes along—nobody could.”

“But I could have done better. Matt, I don’t know anything at all about first aid! The most I ever did at home was spray Bactine on scraped knees. Maybe sometime you could give us a short course?”

“I will. Should have done it months ago.”

“We’ve all been busy. But speaking of first aid, Beth was a wonder! She didn’t do anything in particular—mainly convinced Mr. Jacopetti to take his dentures out. But she calmed him right down, and it looked like she knew what she was doing. You have a student there!”

“I taught her CPR. Gave her a first-aid manual to read at home.”

“Well, she’s a quick study, anyhow. Bright young woman.”

“When she wants to be,” Matt said.

* * *

In clean, dry denim—and despite the shriek of the ventilator ducts, which Abby had warned him about—Matt felt 100 percent better.

It was his experience that bad weather tended to shrink a room. The basement cafeteria, a cavernously large space, had contracted to circles of light around the battery lanterns. It wasn’t just a room anymore. It was a huddling place, a dry cave.

He spoke to Paul Jacopetti and read his blood pressure, which was slightly but not dangerously elevated.

“Doc,” Jacopetti said.

Matt unwound the sphygmomanometer cuff from Jacopetti’s pale arm. It was always the difficult ones who called you “Doc.”

“Yes, Mr. Jacopetti?”

“Can I put my thucking teece back?”

“Certainly. Beth was worried you might pass out. But that doesn’t seem likely at this point.”

And Matt looked away politely while Jacopetti slipped his dentures into his mouth.

“Everybody says angina,” Jacopetti said. “It’s not a heart attack, it’s angina. Okay, good, but how is that better? It feels like a fucking heart attack.”

“They’re not necessarily different. Angina pectoris is the pain you feel when your heart’s not getting enough blood through the coronary arteries. The heart works harder to compensate, and it simply gets tired—the way any muscle hurts if you overwork it. It’s a symptom of coronary disease, but in your case the heart itself seems to be basically sound. We can treat the angina with drugs called beta blockers, which help the muscle ease up a little bit”

Jacopetti was frowning, trying to digest this information. “How long do I take these drugs?”

Probably the rest of your life, Matt thought. If we can find a supply. And keep them from going bad. It was one of those facts of life he still hadn’t grown accustomed to: no new pharmaceuticals. No more free pencils or coffee mugs from drug companies promoting Tofranil or Prozac. No more Tofranil. No more Prozac. No more insulin, come to that, or penicillin, or measles vaccine… not unless he could locate every ounce of every significant drug and store it somehow, refrigerate it, prolong its active life.

Must get this advice to the Boston and Toronto people, Matt thought. Should have done it sooner.

Christ, everything had gotten away from him these last few months. He had been blinkered by his fear for Rachel, transfixed by her slow evolution. But Rachel was gone. It was past time to pick up the fragments of his life, including his work.

“You’ll probably be on medication for some time,” Matt said, “but I can’t tell you for sure until we do a more thorough workup. Not until the storm passes, obviously.”

“If it ever does,” Jacopetti said. “In the meantime… it still hurts.”

“I’ll go up to the pharmacy and find you something. Lie still while you’re waiting, all right? Don’t exert yourself.”

“I’m not going fucking dancing,” Jacopetti said.

* * *

Matt checked in with Abby before venturing upstairs.

She might have fumbled the Jacopetti crisis, but she was doing a fine job as den mother. She had helped Miriam Flett into a dry outfit and settled her onto a mattress with coffee and Oreos. Now Abby was contemplating the possibility of a hot communal meal—“Maybe a little later, if Tom gets his generator working and we can run the microwave. I think that would cheer people up, don’t you? It’s hard enough just keeping track of everybody. Some of us want to move into the hallway—it’s quieter there and closer to the bathroom. Would that be all right?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“People are scattering all over. I don’t know where Beth got to. Or Joey, for that matter. Is the whole basement safe?”

“Oh, probably. But we should encourage people to stay together. And I don’t want anyone running around upstairs.”

“Upstairs is dangerous?”

“It could be. If not now, later.”

“But you’re going up there.”

“Only for a moment, Abby.”

“Matt, you look terribly tired. Maybe you should lie down for a while.”

“Soon. I just have to pick up some pills for Mr. Jacopetti.”

“Poor man. Sick on a night like this. Matt, I had the most terrible thought about him.” She lowered her voice. “I thought he was having a heart attack because it was the best possible way to annoy me. For maybe three seconds, I really thought that! Should I be ashamed of myself?”

“Abby, if I’d been here, I might have had the same suspicion.”

She looked pleased and grateful. “Really?”

“Really.”

“Check in when you come back downstairs?”

He promised he would.

At that moment, the thunder began.

* * *

The storm was complex, peculiar—a whole inventory of storms, Matt thought, one layer upon another.

The stairs ran upward through a cinderblock stairwell at the southwestern corner of the hospital. The ground-floor fire exit had been boarded over, but there hadn’t been time to seal the second– and third-story windows. One had broken. A trickle of rainwater ran down the stairs between Mart’s feet.

The thunder, a sudden new presence, was continuous. It had taken Matt a moment to identify it as thunder, not the approach of some mechanical leviathan from the west. With the thunder, lightning. The lightning lit the stairwell from above with a diffuse reddish-purple glow. It flickered but was never wholly absent.

Matt supposed Abby was right, he was tired, mortally tired—too tired, at any rate, to be frightened of this new evolution of the storm. It wasn’t even a hurricane, it was something larger, still nameless. Peak winds in a hurricane were what, 200 miles per hour? Maximum. And in this tsunami of wind currently breaking against the flank of the Coast Range? Three hundred miles per hour around the eye wall? More? And how powerful was that? Powerful enough to level Buchanan, Matt supposed. And drown half of it in the storm surge.

As he climbed from the hospital basement to the ground floor, he listened to the wind gusting through the upper reaches of the hospital, slamming doors and rattling gurney carts down vacant corridors. And he listened for the voice of the storm itself, a tympani growl, alive, organic, pervasive.

It was out there devouring his town. Uprooting it and devouring it.

He thought of Jim and Lillian Bix, wholly changed and wholly alien, inhabiting their paper-thin bodies only long enough to consummate some process he didn’t understand or wish to understand, the translation of Lillian’s unborn child and the delivery, incidental and trivial, of its derelict hulk. He supposed Jim and Lillian had abandoned their own skins by now. Their skins, like so many others, must have been carried up by the typhoon wind, perhaps to the high atmosphere, somewhere peaceful above the rain.

Matt shook away these troubling thoughts and concentrated on the task at hand.

Pharmaceuticals were stored at various key points around the hospital so that each floor had an accessible supply. These caches were locked—the drugs stored there included narcotics—but Matt had been carrying a key and a duplicate since September. He followed the corridor from the stairwell and cursed himself for not having had the wits to bring a flashlight. Kindle had hooked up a gasoline generator in the basement, but it was only feeding the emergency lights, incandescent bulbs at ten-yard intervals.

The drug cupboard, a room approximately large enough for one person to stand in without touching the shelves, was dark as night. Inside, Matt stood blinking, hoping his eyes would adjust, boxes and labels would reveal themselves in the faint glow leaking from the corridor. They didn’t.

He stepped back into the hallway, pondering the problem. He could go back for a flashlight, but there was an element of time here. He didn’t trust that elevating rumble of thunder, the new intensity of the storm.

He hurried to the nursing station down the corridor. For years, Hazel Kirkwood had been the clerical day nurse on this station. She had her own desk at the rear, away from the busy corridor. Nurse Kirkwood, Matt recalled, had been notorious for her ten-minute breaks every hour, when she would duck outside—or into the stairwell, furtively, in bad weather—to indulge a cigarette habit.

He rummaged in Nurse Kirkwood’s desk drawers. He found an abundant supply of Bic pens, paperclips, and knobby pink erasers; a stapler and a pocket calculator and a single, lonely, plastic-wrapped tampon… and lastly, at the back of the bottommost drawer, a package of filter Kents with a matchbook tucked into the cellophane.

He took the matchbook into the supply cupboard. One match to home in on the propranolol for Paul Jacopetti. Another match to empty a cardboard box of tongue depressors; a third match as he filled the box with anything nonperishable he hadn’t already crammed into his Gladstone bag: antibiotics, painkillers, a bag of sterile cotton. All the while berating himself for not having done this before the storm.

A last match to double-check his work… then he turned and found Joey Commoner blocking the doorway.

* * *

He was too weary to interpret this—Joey’s presence merely baffled him—until he saw the knife.

It wasn’t a big knife, but it caught the faint light from the hallway; the blade glittered as it trembled in Joey’s hand.

Joey said, “I want you to stay the hell away from her.”

His voice was shrill and barely controlled, and it occurred to Matt that, whatever else might be troubling him, Joey was also very frightened of the storm. “You shouldn’t be up here. It’s dangerous up here.”

“I don’t want you near her,” Joey said.

“Can’t we talk about this later?” There was a guncrack of thunder above the general dull roar. “We could end up with a wall on top of us.”

“Fine,” Joey said. “Just tell me you’ll stay away from her and we can go downstairs.”

Matt was suddenly, deeply tired of all this. The storm, Miriam, Jacopetti, Joey. It was all a single phenomenon, and it was too much; it made him weary. He dropped the pharmaceuticals and stepped forward.

Joey thrust the knife wildly. The blade nipped his forearm, slicing his shirt, digging into the skin beneath—a vivid, immediate pain.

Matt stepped back and came up against a shelf. The walls were mercilessly close, there wasn’t room to swing his arms, and Joey was poised at the entrance like a snake.

But Mart’s resentment was irresistible. It propelled him forward. The situation was childish, inappropriate, a frustration not to be borne. He kept his eye on Joey’s knife hand and thought about getting inside the periphery of it, knocking Joey out of the way. In the corridor he would have room to maneuver.

He took a second step forward. Joey shrieked, “Don’t make me do this,” and slashed the air. The knifepoint missed, but narrowly. “Just say you’ll stay away from her! That’s all you have to do! That’s—”

He didn’t finish his sentence. There was suddenly a taller silhouette behind him—Tom Kindle.

Kindle twisted Joey’s arm up behind his back until Joey yelped and opened his hand.

Matt came out of the supply cupboard and backed away from the two men.

Kindle pushed Joey against the wall of die corridor and let him go. Joey spun around. Slowly, Kindle moved away, hands spread. Then he bent and picked up the knife. Peered at it.

“Swiss Army knife,” Kindle said. “Real good, Joey. After you kill him, you can trim his nails.”

“Fuck,” Joey said, rubbing his abused arm, “I didn’t come up here to kill anybody.”

Matt clamped his hand over the cut on his forearm. It was superficial but messy. He’d left a trail of blood spots on the green linoleum floor.

Kindle shook his head. “You came a little too close, in that case. Stupid thing to do. Wave a knife at somebody! There’s only ten of us in town, Joey, is that too many for you?”

No answer.

“Is there some reason you came up here?” Joey nodded. “He fucked Beth.”

Kindle did a small double take. Then he pocketed the knife. “Matt? Any truth to the charge?”

“I taught her CPR,” Matt said. “She’s been getting first-aid training.”

“That’s not what I hear,” Joey said.

“What do you hear?”

“I hear the doctor’s fucking her.”

“Who told you that?”

Self-righteously: “Beth did.”

There was a momentary silence… if you could call it silence, Matt thought, with the wind banging the walls.

Kindle said, “Joey… a woman might say a thing and not mean it. Especially if she thought she was being neglected. A woman might think, What would piss off Joey the most? What could I say to really aggravate this asshole who hasn’t even asked me the time of day since Christmas?”

Joey seemed to ponder the idea. Maybe, Matt thought, on some level, he was flattered by it.

“I just wanted to warn him.…”

“Warn him what? That you’ll kill him if he hangs around your ex-girlfriend?”

“Fuck you,” Joey said mildly.

“Fuck me because I don’t want the town doctor knifed by a jealous asshole? Christ’s sake, Joey, how is it even your business what Beth gets up to? She’s not your wife, and even if she was, adultery’s not a capital crime. You were pissed off and you wanted to wave that knife and make yourself feel better. But that’s so stupid—in the situation we’re in, that’s absolutely suicidally stupid. And that surprises me, frankly, ’cause you’re not as stupid as people think.” Joey looked up, wary of a trap, not sure whether he’d been insulted. Kindle went on: “I know what people say. What they used to say. Nobody held Joey Commoner in high esteem. But that’s changed a little, maybe you noticed. You set up the radio—”