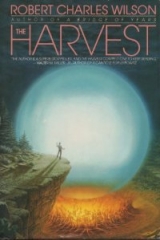

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Because it’s stealing you, Rachel. You’re right, I’m happy we talked. But it doesn’t change anything, does it? You’re going somewhere I can’t follow.”

“Doesn’t that happen anyway? If I’d gone off to college, or—”

“It’s hardly the same. I know you’re not a teenager forever. You go to college, maybe you get married, you have a career, things are different. Of course. But, my God, this is something else entirely. You go to college, I can phone you on weekends. Next year—can you guarantee we’ll even be able to talk to each other?” She looked away.

“So what do we have?” Matt asked. “A few months?” She pondered the question. Her eyes strayed to the harbor, the calm water there. “Maybe a few months. Maybe less.”

“You are going away.”

“Yes.”

“All of you?”

“Yes.”

“Where? When?”

“It’s not—it isn’t altogether clear.” He balled his napkin and threw it on his plate. She said, “Daddy, it works both ways. You made a choice, too. I’m entitled to a little resentment.”

“Oh?”

“Because you’re going to die. And I’m not. And it didn’t have to be that way.”

* * *

He followed the bay road toward home.

“You know I mean to save this town,” Matt told his daughter.

“I’ve heard you say so.”

“You don’t think it’s possible?”

“I’m… not sure.”

“Rachel, listen to me. If you know anything about the future, anything at all about what might happen to this town—to the planet—I need you to tell me. Because we can’t plan for what we can’t imagine.”

She was silent for a long time in the passenger seat. Then she said: “Things will go on as they are now. At least for a little while. Maybe into the winter. After that… people will start to disappear.”

“Disappear?”

“Give up the physical body. Oh, Daddy, I know how horrible that must sound! But it isn’t. It really isn’t.”

“If you say so, Rachel. What happens to these people?”

“They move to the Artifact, at least temporarily.”

“Why temporarily?”

“Because we’ll have a place of our own before long.”

“What are you saying—a human Artifact?”

“That kind of environment, yes.”

“For what purpose—to leave the planet?”

“Maybe. Daddy, these decisions haven’t been taken yet. But the planet is a serious consideration. We’ve left a terrible mark on it. The Travellers have already started cleaning it up. Erasing some of the changes we made. Taking some of the C02 out of the air.…”

“They can do that?”

“Yes.”

“So people disappear,” Matt said. “So Buchanan is empty.”

“We don’t all disappear. Or at least, not all at once. In the short run… What would you call a day like today? Indian summer? Last nice day of the year. Last chance to get in a ballgame, maybe, or go to the park. Well, I think the next four or five months are going to be Indian summer for a lot of us. Our last chance to wear skin and walk around on the earth.”

“Last chance before winter,” Matt said.

“Last chance before something better. But even if you were moving from a log cabin into the Taj Mahal, you’d still want to look around the old place before you locked the door.” Her eyes were vague, unfocused. Her voiced seemed faint. “It’s the cradle of mankind. Not always easy, leaving the cradle.”

Curious, Matt thought, how a sunny day could feel so cold.

* * *

After dinner, she curled up in the easy chair with Dostoevsky in her lap. “How come you still need to read that?” Matt asked. “How come you can’t just remember it?”

“I’m not that good yet.”

“So the library’s not defunct.”

“Not yet.”

“But the time is coming.”

“Yes.” She looked up. He was wearing his jacket; the evening had turned cooler. “Are you going out?”

“Just for a drive.”

“Want company?”

“Thank you, Rache. No. Not this time.”

* * *

He drove down to the parking lot where the summer ferry took tourists over to Crab Pot Island, a dot of National Park greenery in the embrace of the bay. The parking lot was low to the water, and Matt parked facing west, where the sky was still gaudy with sunset, although the light had begun to fade.

He used to come here in the bad time after Celeste died. When you wanted privacy and you lived with a daughter, you found your own retreats. A parking lot was one place where you could sit by yourself in an automobile and be left in peace. People assumed you were waiting for someone. They didn’t look closely. A person could be alone with his grief… could even weep, if he did so discreetly, if he forestalled the kind of helpless sobbing that would attract a stranger’s attention.

He was past that now. But he wanted the solitude.

It was that time of evening when the streetlights flicker on and everything solid seems hollow and flat; when dark thoughts come easily and are harder to ignore.

He wondered what he was trying so hard to save.

What was he sorry to lose, in this new world they were making? War was finished, after all. Disease, apparently, was a thing of the past. Starvation was history. Lies were becoming impractical.

He had never loved war, disease, starvation, or deceit.

So what was it?

What had he loved so much that he turned down the offer of eternal life?

Something evanescent. Something fragile.

A family. Rachel’s childhood. Celeste. The possibility of a human future.

All these things were illusions. He thought of Willy’s IWW banner, an old rag invested with glory by his stubborn defiance. Or the eagles of Dos Aguilas, a beautiful lie.

The sky above the bay was empty.

But the eagles flew, Matt thought. They flew when we believed in them. Willy flew, those ten minutes on the hillside. I will save this town, Matt thought. See if I don’t.

And if I can’t save the town… if it comes to that… then, by God, I will save some part of it.

Someone.

Chapter 18

Annie and Bobby

On the Saturday Matt took his daughter to Old Quarry Park, Annie Gates drove south for an hour on the coast highway.

She had made this drive one weekend out of two—sometimes Saturday, sometimes Sunday—for ten years now.

She had never spoken of it, even to Matt.

She was going to visit Bobby.

* * *

Bobby lived in a room in the east wing of a long, low building in a pine grove near the sea. His window overlooked a broad green lawn and a portion of the lot where Annie parked her car. Of course, Bobby seldom looked out the window. But maybe that had changed. Maybe he was beginning to appreciate the view. Annie hoped so.

The sign at the front door of the building said:

WELLBORNE CARE COMMUNITY

Where Caring Is Commonplace

Commonplace but very expensive. Since Bobby moved in, Annie had been paying Wellborne the equivalent of a Park Avenue monthly rental. She had cut a great many corners. The furniture in her apartment was fifteen years old. Her salad and tuna diet was not for cosmetic purposes. She rarely bought a hardcover book, which had been the most difficult economy of all.

Worth it, of course, to know that Bobby was decently looked after.

She checked in at the desk—Wellborne was still fully staffed, the effects of Contact slow to take hold among its patients—and walked down the east corridor to Bobby’s room, 114.

She’d noticed an improvement on her last visit. Usually Bobby retreated into a fetal curl when he saw her coming. Last time she visited, he had unbent and regarded her with a solemn expression on his face… an expression, however, that Annie could not decipher. Nor could Bobby explain it. He never spoke to her. He spoke to the staff sometimes, simple food and bathroom words. But never to Annie.

Today… her hopes were high.

She crossed her fingers and said a silent, wordless prayer before she knocked and opened the door.

* * *

“Annie!” he said.

Her heart did a startled double-beat. How long since she’d heard his voice?

Almost thirty years, she thought. She remembered quite distinctly, too distinctly, the last words Bobby had spoken to her. Annie, don’t.

He had been nine years old; she had been ten. Annie, he had said. Please don’t.

He looked good today. He was dressed in clean blue jeans and a white cotton T-shirt. The T-shirt said “I LOVE WELLBORNE,” except that “love” was a heart shape. He was still way too skinny. For the last couple of years, Bobby had been a problem eater. Just before Contact, he had bottomed out at 102 pounds. The staff doctor had called to discuss intravenous feeding as an option.

Now he was eating again, and although she could see the staves of his chest through the T-shirt, she could tell he was gaining weight.

His face was terribly thin. His smile was skeletal. But it was a smile, and that was miracle enough. His eyes, deep in their sockets, twinkled at her.

“Hi, Bobby,” she managed through the lump in her throat.

He climbed off the bed where he had been sitting cross-legged watching baseball on TV. “They said I could go out today. Annie! Go for a walk with me?”

“Sure, Bobby,” she said.

* * *

He looked painfully fragile as he hobbled down the front steps onto the lawn, but Annie supposed it really was all right for him to be outside. The medical staff at Wellborne knew what they were doing. And of course, since Contact, Bobby was immortal. Like everyone else. But it was hard to convince herself of that.

He walked like an old man. He was thirty-four years old. He talked like a nine-year-old, which was how old he had been when the accident happened.

Annie walked with him across the sunny lawn. She ventured a question: “Bobby, do you like it here?”

“It’s not bad,” he said. “The food is all right.”

“You want to stay?”

He shrugged. She recognized the gesture, a particular Bobby-shrug. The shrug meant: Don’t know. Don’t want to talk about it.

“Nice day,” she said, helplessly. After all these mute years! Discussing the weather!

Bobby just grinned.

She said, “What have you been doing?”

“Watching TV,” he said. “Remembering.”

“Remembering?”

“I remember a lot. Since they came.” He touched his head—the side of it that was not quite symmetrical—and pointed to the sky: the Travellers. “Annie… guess what I remember?”

She cringed at the thought of what he might remember.

“I remember lawn tag” And he tapped her on the shoulder and went hobbling away.

She pretended to chase, smiling to herself. All that last summer, they had played lawn tag through the long evenings. Daddy was the town doctor in Bruce, a little Canadian prairie town, a one-road grain town; of all the lawns in Bruce, the Gates’s lawn was the biggest.

Lawn tag was a simpleminded chase: under the privet hedge, past the willow tree, mustn’t stray beyond the border of the sidewalk, around back, past the doghouse. Annie, a year older, could have caught Bobby anytime. But she liked the sound of his laughter when he dodged her hand. Some evenings she tagged him once, twice, played hard to get, then let him win. Some evenings she let him win from the start.

Now… she could scarcely believe he was running again. The sunlight was radiant on the big Wellborne lawn; the air was silky cool. He moved in a slip-jointed lope, his jeans threatening to fall off his bony hips. It would have been easy to catch him.

She pretended to chase. Bobby looked back and laughed out loud. Annie savored the sound.

* * *

Sometimes, of course, he made her mad.

The hardest part of Contact had been facing this memory. But it was a memory that had to be faced: Most of Annie had said yes to the Travellers, but this memory part of her had said Annie doesn’t deserve to live.

She was ten. Only ten. A child. Impulsive. Wasn’t every child?

Bobby and Annie were playing on the roof of the house on the hottest day of summer.

It was easy to get onto the roof. Bring the ladder from the old bunk beds in the basement, step onto the tiny balcony outside Annie’s room, up to the steep and baking slope of the shingles. You could lie there and see all the way out past the water tower, past the highway, past the granaries, past yellow quilts of wheat to the horizon.

Bobby was scared of the roof. Annie always helped him up, helped him down. But she sometimes took a shameful pleasure in his fear. Bobby, the younger, often got more attention than he deserved. Bobby was the baby of the family. Annie was expected to help with the dishes. Bobby never did.

Today—well, it was hot. Prairie-summer-itchy-sunburn-tight-clothes hot. Bobby had been whining about it. So she went up on the roof by herself, hoping he wouldn’t follow.

Of course, he did.

He pulled himself over the eavestrough and scuttled up the shingles behind her, clinging to her foot until he could safely lie down. Stay still, silly, and you won’t slip. But that’s not what Annie said.

If you get scared, she said, your hands get all sweaty.

Bobby’s frown deepened.

And if your hands get sweaty… you might slip. He looked at her aghast across a space of cedar shakes and hot air. Annie, don’t.

It’s a lo-o-ong way down, Bobby.

Panicking a little, he grabbed her left foot with both hands. Hey, let go, no fair!

But he hugged it tighter. She was wearing shorts and no shoes. In the hot air, his fingers felt sticky as tar… his touch was an intolerable itch. Bobby! Let go of me!

She kicked her ankle out to shake him loose. Annie, he said, don’t.

Now she was starting to get scared. Her gaze drifted down from the blue deeps of the sky, across those farms, grain elevators, houses, streets, to the rain gutter and the paved walk down below. Mama had put the garbage out. The garbage cans shivered in the rising heat.

She thought of Bobby tumbling down there and carrying her with him.

She shook her foot again, harder.

One hand came loose. Bobby scrabbled against the shingled roof. She kicked again. Annie. Please don’t.

It was peculiar, it was maddening, how calm his voice still sounded.

Annie kicked to pry him loose, felt his hand separate from her ankle. She had turned her head away and when she looked back she caught the briefest glimpse of him as he disappeared over the edge, an expression of vast surprise on his face.

She scrambled down the bunk-bed ladder and looked over the edge of the balcony and saw Bobby on the paved walk beside the garbage cans. She looked for a long time, unable to make sense of what she saw. His head was broken open and some of what was inside had come out.

* * *

When Bobby left the hospital, he was back in diapers. Mama had to change him all the time.

Once, she shook a soiled cotton diaper in Annie’s face. “This is your fault,” Mama said.

Bobby’s head was curiously flat on one side and he didn’t talk, but whenever he saw Annie coming he curled away from her and closed his eyes.

* * *

Mama died a couple of years after that.

Annie had hoped to win back her father’s affection with a medical degree; but he died, too, while she was away at school.

She finished her degree anyhow. Bobby was institutionalized, and the estate was paying for everything, but that money wouldn’t last forever, and she would need a good income—a doctor’s income—to keep Bobby cared for.

Her residency was the hardest part. The sight of a head wound still made her dizzy.

When she took up the partnership with Matt Wheeler, he talked about his wife Celeste and how he had lost her. Annie never talked about Bobby. Bobby was a secret. It kept them apart, but Annie understood that this was what they both needed: something more than friendship, something less than love. Matt was guilty about loving someone after Celeste. And Annie… Annie wasn’t convinced she deserved to be loved.

The Travellers had stirred up these memories, but the Travellers had offered something in return: objectivity, as cool and cleansing as mountain water. The ability to forgive herself.

Annie forgave Annie, a quarter-century down the line.

But it wasn’t her own forgiveness she really craved.

* * *

Bobby tired himself out playing lawn tag, so they retreated to the shade of the patio at Wellborne. Annie brought out two glasses of lemonade from the staff cafeteria. The lemonade was tart and perfect. They sat on the steps, drinking it.

“We’re going on a trip,” Bobby said.

She thought he meant the Wellborne patients. “That’s nice,” she said. “To the seashore, Bobby?”

“No, I mean—us. We’re all going on a trip.”

“Oh. That trip. Yes.”

“Are you excited, Annie?”

“It’s not for some time yet, Bobby. A few months, anyhow.”

“They have to build the spaceship.”

“Yes.”

He shook his head. “I have a lot of growing up to do.”

“There’s no rush.”

“I got kind of… left behind.”

She wanted to say, “I’m sorry!”—but couldn’t find her voice.

“I’m getting stronger,” Bobby said. “Annie—look what I can do!”

A wooden railing ran all around the patio of the Wellborne building. Before she could say anything, Bobby had boosted himself onto the banister. He was clinging to the narrow timber with hands and feet… then he stood up, like a tightrope walker, balancing himself.

His hips stuck out in bony ridges from the loose jeans. His arms, thrown out for balance, were fragile as twigs.

A brisk wind could knock him down from there. She felt a surge of panic. “Bobby, stop it!”

“No, Annie, look” He took two tentative steps. Proud of his balance. Proud of his new life.

“Bobby, you’ll hurt yourself!”

“No, I—”

But she was up without thinking about it, running to him, grabbing him around his painfully thin waist and lifting him down. He was lighter than she expected. He was as light as a nine-year-old.

“Annie, Annie, it’s okay!”

Bobby wrapped his skinny arms around her and pressed his misshapen head against her cheek.

“I know why you’re crying,” he whispered. Did he? Oh, God!

“That was all a long time ago,” Bobby said. “We were kids. It doesn’t matter anymore.”

And Annie cried in her brother’s arms as if she had tapped a reservoir of tears, a well of sorrow ancient and eager for the light.

Part Three

Indian Summer

Chapter 19

Annie and Bobby

Tom Kindle decided he would stay in Buchanan until the end of the World Series. After that… well, the horizon had an alluring look, these rainy autumn days.

Matt Wheeler didn’t appear to approve of the idea.

Kindle walked with him through the empty hallways of the regional hospital. Some of the overhead fluorescents had burned out; some flickered like candles in a cold wind. The building was increasingly spooky, in Kindle’s opinion. Nobody but Matt came around anymore.

“I’d be happier if you stayed,” Matt said.

Kindle didn’t answer. He was concentrating on the pleasure of locomotion. Christ in a basket, it was good to get out of that wheelchair! It was good to be walking under his own steam.

It hurt like hell, but it was good anyway.

Monday he’d made it halfway to the maternity wing and back; today, all the way to Maternity and far beyond, as far as the fabled corridors of Physiotherapy, where empty sitz baths gleamed like strange idols in dim green rooms.

He stumbled once. Matt took his arm. “Don’t overdo it.”

“No pain, no gain.”

“It was a bad break. At your age, you don’t heal as fast as you used to.”

“Thank you, Dr. Kildare.”

“You want me to lie?”

“Every once in a while it might be nice.”

A pause. Matt said, “You’re serious about leaving Buchanan?”

“Yes.” Kindle gritted his teeth and closed his eyes. “Okay, now we turn around.”

They shuffled back through ancient odors of ether and antiseptic. Kindle wore his old jeans and a cotton workshirt. The doctor wore his hospital gown over a similar outfit. We don’t look all that different, Kindle thought. He caught their reflection in a rainy corridor window. Not doctor and patient. Just two guys who ought to shave more often. Two guys with similar worry lines. Different pain.

Matt said, “You have somewhere in particular to go?”

“It’s a big country… I haven’t seen it all.”

In fact, he was thinking about the Wind River Range, the Tetons, that area. He hadn’t seen Wyoming for about twenty-five years.

“What about the Committee?”

“I never signed on to salvage Buchanan. I barely lived here, you know, before Contact. The Committee’ll get on without me.”

“You said you’d do radio.”

“Yeah, yeah, I’ll do radio. I’m not leaving yet.”

“There’s a meeting at the end of the week.”

“Right, I’ll be there.”

“I want you to talk to me before you leave,” Matt said. “Maybe I can change your mind.”

Kindle promised he would, though it rubbed him the wrong way. No strings attached, damn it. He’d leave when he felt like it. Stay or go as the spirit moved him.

It was how he’d lived his life. Why change now?

Matt left him alone in his room. Kindle checked the TV, but there was nothing but fuzz. All they showed on TV anymore was a couple of hours of news per day. Plus the Major League playoffs.

* * *

The first-of-November Committee meeting was brief and morose. Five people showed up in addition to Kindle and Matt Wheeler. Joey Commoner and Beth Porter were two of them. Abby Cushman, the somewhat ditzy farm lady, failed to appear. Paul Jacopetti unfortunately did. The pessimistic ex-tool-and-die maker issued his usual evil-minded prophecies, including a prediction that the Helper recently arrived at the City Hall Turnaround would murder them all while they slept. Poison gas, maybe. Matt seemed too dazed to refute this paranoia, and Kindle listened with disgust.

After that they held their first election. Matt stood for chairman. His single opponent was—inevitably—Paul Jacopetti, who didn’t think Matt should run unopposed, “although of course this whole exercise is futile.” There was a show of hands and Matt took the vote six to one. (“Figures,” Jacopetti said.)

Old business. Kindle promised he would drive down to Causgrove Electronics the next day and look for a ham set.

“A lot of those stores are closed,” Matt reminded him. “Call first. Or call the owner and see if he’ll let you in.”

“Or I could jimmy the lock.”

Matt shot him a disapproving look. “I don’t think it’s come to that.” Maybe, Kindle thought. Or maybe not.

* * *

But he did as Matt asked: phoned the store, no answer, phoned three Causgroves out of the book until he found the one who owned the shop.

“You’re right, Mr. Kindle, the front door’s locked. Locked it myself. Force of habit, I guess. -But the back is open. You can get in that way.”

“You want to meet me there?”

“For what purpose?”

“Well, I can write you a check. Unless you want cash.”

“Please, don’t bother. Just go ahead and take what you need.”

“I’m sorry? What?”

“We had a reasonable stock last time I looked. I presume you can find the stockroom, or just root around the displays. If we have what you want, take it.”

“Pardon me. You said—take it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Just—take it?”

“Yes.”

“Just like that?”

“Yes. I’m happy to see the goods serving a purpose. I thought they’d all turned into scrap metal. Please, take whatever you want. But it’s nice of you to have called, Mr. Kindle.”

The connection broke at the other end. Kindle stared at the phone for a while.

* * *

His first experience with a motor vehicle since the accident wasn’t his pickup truck, which had been towed or trashed, but a car Matt Wheeler left for him in the hospital lot: a little blue Japanese device. Kindle was long-legged, and the act of climbing inside this automobile left him feeling like he’d been folded into a mailbox. His knees bumped the wheel until he figured out how to lever back the seat. Everything was digital. The dashboard looked like a cockpit display.

But it was transportation, what the hell. Maybe, when his leg didn’t hurt so damn much, he would take himself to a car dealership. Maybe the price of a new car had dropped since Contact. Maybe to zero. He wondered what it would be like to drive one of those bullet-shaped vans he used to see on the road. It would be nice to have an enclosed space to keep a few things out of the rain.

This morning, a Tuesday morning, the roads were wet and empty. The rain fell in mists; the windshield fogged until he figured out how to run the heater.

Driving west from the hospital, Kindle was impressed with the stillness of the town. It was as if some languorous, fatal calm had settled over Buchanan. He counted the cars he passed—eight altogether, their brake lights making comet-tails on the slick asphalt. No pedestrians. Most of the shops were dark.

It resembled a ghost town, Kindle thought, but no one had really left. What were all those people doing?

He parked in a no-stopping zone. Anarchist outlaws of the world, unite. He extracted himself from the car, moaning when his bad knee knocked against the steering column.

Causgrove had been correct: The front door of the shop was locked, but the door facing the service alley opened at the turn of a knob.

Kindle switched on lights as he entered the building. He realized as soon as he found the dimly daylit front room that shopping was going to be harder than he’d expected. The racks were full of indistinguishable black boxes with endless, cryptic numeric displays. Some of these items were marine radios, some were ham rigs, some served no obvious purpose. “Should have studied up on this,” Kindle said aloud.

“You just have to know what you’re looking for.”

He was startled by the voice, and he turned thoughtlessly on the axis of his left foot. A flare of pain sizzled up the leg. “Ouch, goddamn it!” He steadied himself on a steel rack. “Who’s there?”

It was Joey Commoner.

* * *

Joey came out of the shadows behind the cash counter. He looked like a hood, Kindle thought, but not a dangerous one. The kind of suburban white kid who dresses like a drug dealer but doesn’t know any. He stood with his hands in the pockets of his leather jacket and an unreadable expression on his face.

“Knew you’d show up,” Joey said.

“You were waiting for me?”

“What you said at the meeting last night…”

“What about it?”

“Figured you wouldn’t know what you wanted.” Kindle glanced again at the relentless racks. Kid had a point. “So are you here to help or did you just want the fun of watching?”

“You need a transceiver,” Joey said. “Show me one.”

Joey pushed away from the counter and sauntered over to a wall display. Yet more big black boxes. Some of them had microphones attached. Joey said, “How much are you planning to spend?”

“Do you see anybody behind the register?”

“We’re ripping this off?”

“Not exactly. I talked to the owner. He says we’re welcome to take anything we want.”

“What, for free?”

“No money down, no monthly payments.”

“Shit,” Joey said. “That’s weird. I knew these people weren’t human.” He turned his attention to the stock. “So we want the best, right?” He put his hand on a huge rig. There was a Japanese brand name on the face of it, next to more knobs and technical graffiti than Kindle cared to look at. “This is a three-hundred-watt transceiver. They come more powerful, but I don’t think we need it.”

“You know ham stuff? How come you didn’t say anything at the meeting? Save me the trouble?”

“I don’t know much. Mainly theory. I know how radio works. I never got a license or anything.”

“One up on me.”

“Uh-huh. Probably we could use an ARRL Manual, too.…”

“Which?”

“The book on the rack over there? Looks like a phone book?”

Kindle considered his leg. The ache, which never ceased, was cranking up toward real pain. “Tell you what… I’ll carry the book if you carry that machine.”

“It’s a transceiver. Or you can call it a rig.”

“All right, Christ, it’s a transceiver. Can you carry the fuckin’ transceiver?”

Joey smiled. “Should have brought your wheelchair.”

“Smart-ass.”

* * *

Joey rooted in the stockroom for a boxed unit with a manual, then loaded it into the trunk of Kindle’s car. “I appreciate the help,” Kindle said. “You’re not done yet.”

“No?”

“Think about it. You want to be a radio station. So you need more than a box. You need—”

“An antenna.” It was obvious. He felt a little stupid. “Well, shit.” He squinted at the kid. “You know about antennas?”

“Could figure it out.”

“They stock ’em here?”

Joey nodded. “But we should come back with a truck or something. We’re talking about maybe a big beam antenna. You got a three-hundred-watt transceiver, so you want a big antenna and a big tower to do it justice.”

“Why don’t I just go home and let you take care of it?”

Joey backed up. “I didn’t volunteer for this.”

“No, hey, I didn’t mean it that way—”

“I mean, fuck you if you want me to do your job.…”

“No—”

“Just wanted to help.”

“So help.” Kindle slammed the trunk shut. “Let’s not stand here in the pissin’ rain. We’ll come back with a truck. But maybe tomorrow, all right? My leg hurts.”

Joey gazed at him. “You broke it?”

“Yeah.”

“How?”

“Fell down a mountain.”

“Uh-huh,” Joey said. “You look too old to climb a mountain.” Kindle sighed and took a pen and notepad from his shirt pocket. “Write down your phone number. I’ll call you about the antenna.”

“Told you I’m not doing your work for you.”

“You don’t have to work, goddamn it, you only have to point.”

“I just like the electronics.”

But Joey wrote his number down.

* * *

There was a baseball game on TV that night. There had been a long hiatus after Contact, then the season had picked up where it left off. The World Series would run into cold weather, but with all these domed stadiums Kindle supposed that wasn’t a problem.

He had watched all these games. Everything else on TV since Contact had been bizarre and kind of frightening, even such laudable events as the relief flights to the Third World. The food flights had been good, but they had also been operated with scary precision. There was something unnerving about all those military planes in V formation, even if their cargo bays were filled with wheat.

Now the relief flights appeared to have stopped; the implication was that the refugee populations of the world had found some new way to get along… or had “discorporated,” a word Kindle remembered from his youth. Feeding the poor had been a stopgap effort, a bridge to that great unspoken mysterious millennium Kindle felt bearing down on him like a runaway locomotive.

But baseball went on. The NBA hadn’t started a new season, football was finished, but a decision had been made in some telepathic congress: The World Series would be played out come hell or high water.

Maybe in Spain it was soccer, or in Russia it was hockey or chess or whatever the hell they played over there, but games still mattered. According to Matt, there were still Little League games being played in Buchanan, even some pick-up football on the high school field. Whatever it was people were turning into, they still liked to get out on the turf and chase a ball.