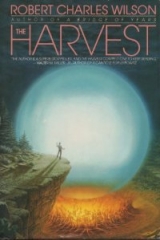

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

She had the idea that Joey was a reservoir of motions, that he did much of his thinking with his body. She had to work to stay close to him as he scrambled among the weeds and rocks up to the grassy margin of the cemetery. He moved with a feverish agility. If his motions were ideas, Beth thought, they would be strange ones—deft, delirious, and unexpected.

Maybe they would be dreams. The night had begun to seem dreamlike even to Beth. The Artifact had risen in the sky like a big backward moon. It looked faintly yellow tonight, a harvest-moon color. Beth was as frightened of the Artifact as everybody else, but she took from it, too, a curious exaltation. Hanging in the sky above her, casting its light across the trim grass and gravestones, the Artifact was a refutation of all things safe and secure. People lived their stupid lives in their stupid houses, Beth thought, but this new moon had come to remind them that they lived on the edge of an abyss. It restored vertigo to everyday life. That was why people hated it.

Joey had gotten ahead of her. He moved in the shadows of the trees, uphill to the three stone mausoleums where Buchanan’s best families had once interred their dead. Too good for burial, the bodies had been enclosed in these stone boxes. To Beth it seemed doubly macabre. She had stood once on a hot spring afternoon and peered through the small barred opening into the darkness inside one of these tombs, a garage-sized building inscribed with the name of the JORGENSON family. The mausoleum had been frigid with undisturbed winter air. She felt it on her face like a breath. It must be winter in there always, she thought. And backed away with a shuddery, instinctive reverence.

It was a reverence Joey obviously didn’t share. He raised the can of cherry-red spray paint to the wall of the building and began to work the nozzle.

He worked fast. Beth stood back and watched. He covered the east exterior wall of the mausoleum with a motley collection of words and symbols like a machine printing some indecipherable code. The symbols were commonplace but Joey made them his own: swastikas, skulls, Stars of David, crosses, ankhs, peace symbols. She couldn’t guess what they meant to him. Maybe nothing. It was an act of pure defilement, empty of meaning. The hiss of the spray can sounded like leaves tossing in the night wind.

He turned to the gravestones then, moving along the hillside so fast that Beth had to run to keep up. He made red Xs across the engraved names and dates. Now and then he would pause long enough to make a skull or a question mark. In the light of the Artifact, the red paint looked darker—brown or black on these chill white slabs.

It must be like sex for him, Beth thought. This frantic motion. This ejaculation of paint.

It was a funny thought but truer than she realized. When the can was empty Joey threw it at the sky—at the Artifact, maybe. The can looped high up and came down noiselessly among the graves. Beth approached him, and as he turned she saw the outline of his erection pressing against his jeans. She felt a shiver that was both attraction and revulsion.

He pushed her down—she let herself tumble—into the high grass at the edge of the woods. It was late, they were alone, and the air was full of scary electricity. A cool wind came in from the ocean with the battery odor of midnight and salt. She let him pull up her skirt. He was like a shape above her, something out of the sky. She lifted up for him as he tugged her underpants away. He breathed in curt, hard gasps. His penis was as hard and as chilly as the night. It hurt for a minute. And then didn’t.

* * *

Was this what she wanted from him? Was this why she had adopted Joey Commoner the way an alcoholic adopts the bottle?

No, not just this. Not just this push and shove and brief oblivion and sticky aftermath.

Joey was dangerous.

She wanted him—not in spite of that—but because of it.

This was a bad and troubling thought, allowable only in the neutral calm that came after fucking.

He pulled his pants up and sat beside her. Suddenly embarrassed by her own nakedness, Beth smoothed her skirt. Fucking in a graveyard, she thought. Christ.

She followed Joey’s gaze out across the night. From this hill she could see the lights of downtown Buchanan and the night shimmer of the sea. “Someday we’ll do something big,” Joey said.

Joey often made this ponderous statement. Beth knew what he meant by it. Something really dangerous. Something really bad.

He put his arm around her. “You and me,” he said.

He’s like some kind of wild animal, Beth thought. A wild horse maybe. A wild horse you befriended and who lets you ride him. Ride him at night. To some wild place. To the edge of a cliff. She closed her eyes and saw it. Saw herself riding Joey the wild horse to the brink of a limestone butte. Long drop to the desert floor. Some starry night like this. Just Beth and her wild horse and that soaring emptiness.

And she spurs him with her heels.

And he jumps.

* * *

Later they saw the lights of the little golf cart the security guard rode through Brookside every night, and they ran down the hill and across the graves to the duckweeds and into the dark ravine where the river flowed. Beth imagined she could hear the guard’s hoots of surprise as he discovered the vandalism, but that was probably her imagination. Still, the idea was funny; she laughed.

Joey sped away past these houses full of sleeping people, wending a crooked path down Buchanan’s side streets… past the house of Miriam Flett, who turned in her bed at the sound of a motor and Beth Porter’s wild laugh, and thought in her sleep of how strange the town had lately become.

Chapter 3

Machines

Jim Bix was ugly the way President Lincoln was said to have been ugly: profoundly, distinctively.

His face was long and pockmarked. His eyes, when he focused the full beam of his considerable powers of attention, resembled poached eggs cradled in cups of bone and skin. He wore a brush cut that emphasized his ears, which stood out not merely like jug handles—the image that sprang to mind—but like the handles on a kindergartener’s clay jug, or the discarded work of a tremulous potter.

It was also a face transparent to emotion. When Jim Bix smiled, you wanted to smile along with him. When he grinned, you wanted to laugh. He was conscious of his own guilelessness, Matt knew, and oddly ashamed of it. He avoided poker games. He told lies seldom and never successfully. Matt had once witnessed Jim Bix attempting a lie: He told Lillian he had broken one of her Hummel figurines, protecting the guilty party, the family dog, whom Lillian despised. The lie had been so incoherent, so patently manufactured, and so blindingly obvious that everyone present had laughed—including Lillian but excepting Jim himself, who blushed and clenched his teeth.

Jim Bix, in other words, was a nearly unimpeachable witness. Matt kept that in mind as he listened to what his friend had to say. From anyone else, it would have been unbelievable. Absurd. From Jim…

Belief, that cautious juror, withheld a verdict.

* * *

Matt opened the door a quarter of an hour before midnight that August evening and welcomed in this ugly and obvious man, his friend, who was also one of the best and most scrupulous pathologists Matt had encountered. Jim accepted Mart’s offer of coffee and settled leadenly into the living room sofa. He was 6’3” from toe to crewcut, and he dominated any room he inhabited, but tonight, Matt thought, he looked smaller—a sag had crept into his shoulders, and his frown hung on his face like a weight. He took the coffee wordlessly and cradled the cup in his hands.

Matt interpreted all this as fatigue. Early in the year, Buchanan General had been certified as a regional trauma center. This was good news for the administration; it meant prestige and more reliable funding. Among staff, the reaction was mixed. They were handed a wish-list of technological goodies—respirators, bronchoscopes, a new pediatric ICU. But they also inherited a number of difficult cases that would ordinarily have been transferred to Portland. For Pathology, it had meant a huge new work load without the prospect of additional staff. Jim had been working evenings for most of two months now. Of course he was tired.

Rachel had gone to bed, and the house, with its curtains drawn against the dark, seemed uneasy in its own silence. Jim cleared his throat. Matt said, “How is Lillian?”—disguising the fact that he’d seen her this afternoon.

“Seems fine,” Jim said. “Kind of quiet.” He ran a large hand through his stubble hair. “We don’t see much of you and Annie lately.”

“Lousy hours. Yours and mine. I hope you can make it on Friday.”

“Friday?”

“Friday night. A little get-together. I called about it last week.”

“Yeah, of course. I’m sorry, Matt. Yeah, we’ll try to be here.” Matt said, “You look punch-drunk.” No argument. “Is it that serious?” A nod.

“Then you better tell me about it. And drink your damn coffee before it gets cold.”

“Something’s fucked up at the hospital,” Jim said, “and nobody wants to listen to me.”

* * *

It had all happened, he said, very quickly.

It started earlier in the week. He took a couple of complaints from the staff doctors that hematology results were coming back funny. Standard tests: Smack 24s, red counts, white counts. Patients with borderline anemia were showing radically low hemoglobin totals, for instance.

New blood was drawn, new tests ordered, and he promised to oversee the results personally.

“Everything was kosher. I made sure of it. But the results… were worse. 7’

Matt said, “Significantly worse?”

“I couldn’t go to staff with these numbers. What was I supposed to say? I’m sorry, Doctor, but according to the lab your patient is dead. When the patient is actually sitting in the dayroom watching Days of Our Lives. And the bad thing is, it’s not just a few samples now—now everything is coming up fucked. Hematology, hemostasis, immune response, blood typing. Suddenly we can’t run any kind of blood assay without getting completely Martian numbers out of it.”

“A lab problem,” Matt said.

“Can you think of any kind of problem that would screw up all these results? Neither could I. But I thought about it. I talked to the chief resident, and he agreed we should farm out the most urgent tests to other labs until we track down the problem. Okay, we do that. This was a couple of days ago. We start looking at everything. Some weird contamination coming through the air ducts. Bad sterilization. Voltage spikes on the A.C. lines. We clean it all up. We try some basic tests on a sample of whole blood from the freezer. And everything comes out within reasonable limits.”

“So far so good.”

“Exactly. But I’m not entirely convinced. So we draw some fresh blood from a healthy donor, and we put it through the cell counts, hemoglobin counts, reticulocyte counts—plasma fibrinogen, platelet counts, one-stage assays—”

“And it comes up fucked,” Matt guessed.

“It not only comes up fucked,” Jim said, “it comes up so completely fucked that we might as well have been running tests on a glass of tepid well water.”

* * *

Matt felt a touch of fear, as tentative as a cold hand stroking the back of his neck.

If there was some new pathology out there, and if it was common enough to be manifesting in all of Jim’s blood samples… but why hadn’t anyone else seen it? “What about the tests you farmed out?”

“They’re not back. We phone the private labs. They’re sorry, but the results don’t seem quite… plausible. They want to know if the samples were damaged in some way, maybe contaminated in transit. Meanwhile, the chief resident gets a call from the hospital in Astoria. Are we having blood-count problems? Because they are. And so is Portland.”

“Jesus,” Matt said.

“That’s the situation this morning. Everybody’s going crazy, of course. Phone lines to the CDC are jammed. This afternoon, I take some fresh blood and I put it under a microscope. Has anything changed? Well, yeah. Suddenly there’s foreign bodies there. Like nothing I’ve ever seen before.”

Matt put aside his coffee cup, which had grown cold in his hands. “Foreign bodies? What—viral bodies? Bacteria?”

“On a slide they look kind of like platelets. Roughly that dimension.”

“You’re sure you’re not looking at platelets? Maybe deformed in some way?”

“I’m not that stupid. They don’t aggregate. They stain differently—”

“I’m not questioning your competence.”

“Fuck, go ahead. I would, in your place. The weird thing is that these organisms weren’t there the day before. I mean, do they reproduce that fast? Or what, were they hiding?”

“It’s just so bizarre. If you were looking at blood from patients with a common pathology, okay, but—the patients are healthy?”

“Far as I can tell, the condition is not making anyone particularly sick.”

“How could it not? White counts are low?”

“White counts are missing.”

“This is ludicrous.”

“Obviously! I know that! I’ve been reminded of it at great length. If you want me to make sense of it for you, I can’t.”

“But it’s harmless?”

“I’m not saying that. I’m not saying that at all. It’s an ongoing situation. It scares the shit out of me, actually. You know what I notice? Everybody I run into seems to have a case of the sniffles. You see that in your work, Matt? Nothing serious. But everybody, every individual. Walk into a crowded room and count the Kleenex. Check out a drugstore. Big run on OTC decongestants. My pharmacist says he can’t keep aspirin in stock. Is this a coincidence?”

Matt said, “Well, Christ—I’ve got a bottle of Dristan half-empty in the bathroom cupboard.”

“Uh-huh,” Jim said. “Me too.”

Annie had been sniffling at work. And Lillian, come to that. Beth Porter.

And Rachel. My God, he thought. Rachel.

* * *

The two men looked at each other in the sudden silence of shared fears. Matt said, “What do you want?”

“I just want to talk. Everybody I talk to at the hospital, everybody on staff—either they want a quick fix or they just don’t want to know, period. And I want us to drink. Not this fucking coffee, either.”

“I’ll break out a bottle,” Matt said.

“Thank you.” Jim seemed to relax minutely. “You know why I really came here?”

“Why?”

“Because there are very few sane people on this planet. And you happen to be one of them.”

“You got a head start drinking?”

“I mean it. I always thought that about you. Matt Wheeler, one sane individual. Never said it. Why wait?”

Why wait? This was more of an admission than he might have intended. Matt did not pause on his way to the liquor cabinet, but he asked, as casually as he could manage, “You think we’re all dying?”

“It’s a possibility,” Jim Bix said.

* * *

They talked it through several rounds of drinks, covering the same territory, deciding nothing, speculating, probing, perhaps, the limits of each other’s credulity. It was Jim, drunk and tired, who first used the word “machines.”

Matt thought he’d misunderstood. “Machines?”

“You’ve heard of nanotechnology? They move around atoms, make little gears and levers and things? They can do that now.”

“You have some reason to think that’s what you’re looking at?”

“Who knows? It doesn’t look like a machine, but it doesn’t look like a cell, either. Looks kind of like a spiky black ball bearing. There’s no nucleus, no mitochondria, no internal structure I can look at with the equipment at the hospital. I wonder what a good research lab would find if they took one apart.” He showed a thin smile. “Gears and levers. Betcha. Or little computers. Little subatomic integrated circuits. Running algorithms on nucleotides. Or something we can’t even see. Circuits smaller than the orbit of an electron. Machines made out of neutrinos. Held together with gluons.”

He grinned, not a happy expression. Matt said, “Sounds like Jack Daniel’s talking.”

“Two advantages to getting drunk. You can say ridiculous things. And you can say the obvious thing.”

“What’s the obvious thing?”

“That this is not entirely unconnected with that rucking unnatural object in the sky.”

Maybe, Matt thought. But he had heard everything from hot weather to diaper rash blamed on the Artifact, and he was wary of that line of thinking. “There’s no evidence…”

“I know what organic disease looks like. This is something altogether else. This didn’t happen over the course of a month, Matt. We’re talking about days. Practically hours. Bacteria can reproduce that quickly. But if these were bacteria they would have killed us all by now.”

But if that were true—“No,” he said. “Uh-uh. I don’t want to think about that.”

“You and the rest of the world.”

“I mean it. It’s too frightening.” He looked into his glass, vaguely ashamed. “I accept what you’re telling me. But if it’s somehow connected with the Artifact—if these things are already inside us—then it’s game over, isn’t it? Whatever they want—it’s theirs. We’re helpless.”

There was a silence. Then Jim put his glass on the side table and sat up. “I’m sorry, Matt. I did a shitty thing. I came here and dumped my problems in your lap. Not fair.”

“I’d rather be scared than ignorant.” But it was late. They had gone beyond productive conversation. Matt was afraid to check his watch; he had office hours to keep in the morning. Plague or no plague. “I need to sleep.”

“I can let myself out.”

“You can sleep on the sofa, you asshole. Is Lillian waiting up?”

“I told her I might spend the night at the office.”

“Spend some time with her tomorrow.” Jim nodded.

Matt gave him a blanket from the closet in the hall. “We’re in some pretty deep shit here, aren’t we?”

“Pretty deep.” Jim stretched out on the sofa. He put his glasses on the table and closed his eyes. His unhandsome face looked pale. “Matt—?”

“Hm?”

“The blood I took? The fresh sample? The blood I looked at under the microscope?”

“What about it?”

“It was mine.”

* * *

Matt allowed his alarm clock to wake him—savoring a long moment of twilight sleep, when the things Jim had told him were still submerged, a presence felt but not explicit. Then woke to a raw headache and terrible knowledge.

It was a fine, sunlit morning. He forced himself through a shower and put on clothes that felt like 100-grit sandpaper. Rachel was in the kitchen fixing breakfast. Fried eggs. Matt looked at his plate. Only looked.

“Are you sick?” his daughter asked.

“No.” Unless we all are.

She sniffled. “Dr. Bix is asleep on the sofa.”

“He’s not due at the hospital until noon. We should let him sleep. He needs it.”

She shot him a quizzical look but let the subject rest.

Rachel believed in the power of a home-cooked breakfast, and she insisted on cooking it herself. The pattern had been established during Celeste’s illness and continued after her death, when Matt had been inclined to leave breakfast and dinner in the hands of McDonald’s and Pizza Hut, respectively. Matt had supposed it was Rachel’s way of mourning, packaging her grief in these daily rituals. By now it had become simply habit. But she did the work solemnly and always had. More than solemnly. Sadly.

Since last year, that sadness had seemed to infect all the other aspects of her life—the way she walked, the way she dressed, the mournful music she played on the stereo Matt had given her for Christmas. In her final year of high school, she had pulled a perfunctory B average—her aptitude for schoolwork tempered by a blossoming despair.

He picked at the eggs while she dressed for the day. When he saw Rachel again she was heading out the door, meeting some friends, she said, at the mall. She smiled distantly. “Dinner the usual time?”

“Maybe we’ll go out,” Matt said. “Dos Aguilas. Or maybe the Golden Lotus.”

She nodded.

“I love you,” he said. He told her so often. Today, it came out sounding awkward and ineffectual.

She gave him a curious look. “You too, Daddy,” she said. And smiled again.

It wasn’t a happy smile. It said, Are things really as bad as that? Matt tried to smile back. He guessed it was an appropriate answer. A brave but unconvincing grin. Yes, Rachel. Things are at least as bad as that.