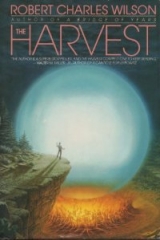

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

No one spoke.

“Okay. I know we haven’t elected a chairman, but does anybody object if I appoint Tom Kindle as our radio committee?” No objection. “Tom, you ought to be mobile by the end of the month. I suggest you price a decent ham radio rig—there’s an electronics shop down by the marina, I recall. In the meantime, I can find you some books on the subject.”

“Okay… but I’m not licensed, Matt.”

“Do you suppose the FCC gives a damn right now?”

Kindle grinned. “I spose not.”

Miriam Flett put up her hand: “Dr. Wheeler… are we expected to pay for this radio nonsense?”

“We should talk about funding. But I’m prepared to underwrite the Radio Committee for the time being.”

Makepeace and Ganish both offered to chip in; Matt said he’d get back to them—no money was being spent until next week at the earliest.

“There’s a fifth category,” Jacopetti said. “One you neglected to write down.”

Matt glanced at the chalkboard. “What would that be, Mr. Jacopetti?”

“Defense.”

A chill seemed to settle in the room. Joey Commoner uttered a small, scornful laugh.

Kindle said, “We get the point, Mr. Jacopetti, but as you yourself said, we’re kinda outnumbered. If this is the Alamo, we might as well pack it in.” Jacopetti folded his hands on his belly. “I agree. And I think it’s the likeliest prospect. We don’t fit into this new world of theirs. They’ll get tired of us, and then they’ll dispose of us.”

“Not my kids,” Abby Cushman said faintly. “They wouldn’t do that to me… not my grandchildren.”

Jacopetti gave her a stony look. “I wouldn’t count on that. We have to be prepared—isn’t that why we’re here, Dr. Wheeler?”

“I don’t think that’s something we can prepare for, Mr. Jacopetti. And I don’t think it’s as likely as all that. No one’s threatened us yet.”

“And no one will.”

* * *

A new voice. Heads turned toward the doorway. A small presence there. It was Cindy Rhee.

Matt had the involuntary thought She ought to be dead by now.

He was visited by the memory of Ellen Rhee wiping drool from her daughter’s chin as Cindy’s eyes roamed aimlessly and without focus.

That was before the intervention of the neocytes, this miracle cure. Now Cindy Rhee was walking—albeit stiffly—and talking, although her words were solemn and curiously deliberate.

“She’s one of them,” Miriam Flett announced. “She shouldn’t be here.”

The twelve-year-old focused her eyes on Miriam before Matt could frame an answer. “I won’t stay if you don’t want me to, Miss Flett. I came so that someone could speak for us.” The collective, the inclusive, the universal us. She turned to Matt. “Dr. Wheeler, it’s probably sensible, what you’re doing here. But Mr. Jacopetti is wrong. We’re not a threat to you.”

“Cindy,” Matt said, “are you speaking for everyone? All the Contactees?”

She remained in the doorway, a small silhouette. “Yes.”

“How is that possible?”

She shrugged.

“Cindy, if you really know what’s going to happen—next month, next year—I wish you’d tell us.”

“I can’t. It hasn’t been decided yet, Dr. Wheeler.”

Paul Jacopetti had turned a shade of-brick red that caused Matt to speculate about hypertension. “Who is this kid? And how does she know my name?” To Cindy: “What were you doing, listening through the door?”

“She’s a patient of mine,” Matt said. “She—”

“They know everything” Miriam interrupted. “Haven’t you figured that out? We don’t have any secrets from them.”

Jacopetti stood up. “I vote to have her removed. She’s a spy, obviously.”

“I’ll go,” Cindy Rhee said.

“No,” Matt said. Lacking a gavel, he slapped shut his notebook. “I was about to declare a coffee break. Cindy, please stay until we reconvene. Twenty minutes.”

* * *

He asked Cindy to sit in one of the boardroom chairs and pulled up a second chair in front of her. He felt he should take the opportunity to examine the child, though he couldn’t say what moved him—sympathy, curiosity, dread. He took a penlight from his shirt pocket and shone it into her eyes.

The others had crowded around the coffee urn, talking in low voices and sparing an occasional glance at Matt and Cindy. He hoped he hadn’t jeopardized his credibility by talking to the girl.

Tom Kindle sat apart, thoughtful in his wheelchair.

Cindy’s pupils still seemed slow to contract, but their reaction was equivalent and otherwise normal. She tracked the penlight adequately when he moved it right to left, up and down.

He touched her forehead; the skin was cool.

“Thank you for being worried about me, Dr. Wheeler. I’m all right.”

“I’m glad, Cindy. It’s good to see you walking.”

“But you think it’s strange.”

“I’m happy about it. But yes, it seems strange to me.”

More than that. He wondered what kind of miracle it really was. He wondered what was inside her skull right now. Normal brain tissue, somehow regenerated? Or something else? Something fed by blood like dark molasses?

She seemed to sense the thought. “They had to work on me before Contact, Dr. Wheeler, because I was so sick. So I’m a little farther on than most people.”

“That’s why you came here?”

“Partly. Partly because even Mr. Jacopetti can’t be too scared of a twelve-year-old.” She suppressed a smile. The smile looked authentic. It was the way she had smiled last year, before the neuroblastoma put an end to all her smiling. “We aren’t dangerous to you. It’s important to understand that. You’re right about the future. It might be difficult. But we’re not the danger.”

She was still woefully thin.

“You mean to help,” Matt said. “I appreciate that. But it would be better if you didn’t stay.”

“I know. Thank you for the examination.”

She stood up and seemed ready to leave, then frowned and tugged at his sleeve. “Dr. Wheeler…”

“Yes?”

“It’s about your daughter.…” He felt a deep interior chill. “Rachel? What about her?”

“You should talk to her. You haven’t really talked to her since Contact. She misses you.”

“How do you know that?”

It had become the great unanswerable question. Cindy just shrugged—sadly.

“Talk to Rachel, Dr. Wheeler.”

* * *

There wasn’t much more meeting. Chuck Makepeace said they should invest in a few copies of Robert’s Rules of Order and elect a chairman at the next meeting. Matt agreed. Tim Belanger volunteered to take minutes next time. Abby Cushman said they would need a name—“You can’t have us just be nameless.”—and were there any suggestions? Abby herself thought “Committee of the Last True Human Beings” would be good.

“Too confrontational,” Makepeace said. “That’s not what we’re about.”

Jacopetti raised his hand. “Committee of Cockeyed Optimists. Council of Lost Causes.”

Matt said he thought it could be the “Emergency Planning Committee” for the time being. Heads nodded, though Abby seemed disappointed.

It was past ten o’clock and people were eager to leave. Matt asked them to write their names, addresses, and phone numbers on a piece of paper, which he would photocopy and distribute to everyone on the list along with an announcement of the next get-together. Meeting adjourned. Beth and Joey Commoner were first out the door; Miriam Flett, last. Matt stood at the window watching cars pull out of the parking lot.

Tom Kindle wheeled himself to the door. “Care to push me as far as the elevator? Jeez, I hate this fuckin’ chair.”

“You’ll be walking before long.” Matt guided the chair down the semidarkened corridor. The walls were painted a shade of green that was supposed to be soothing but looked, under the ceiling fluorescents, unearthly. Kindle wouldn’t be alone in this cavernous building—there was still a skeleton night staff on duty—but in some other sense he would be very alone, and Matt felt sorry for him.

“So,” Kindle said, “are you going to take the girl’s advice?”

“You heard that?”

“A little. None of my business, of course. Didn’t know you had a daughter.”

“I used to.” He rang for the elevator and worked to keep the bitterness out of his voice. “I’m not sure I do anymore.”

Chapter 16

The Battle of U.S. 95

The problem, John Tyler thought, was that all the armies had gone home, all the factories had closed their doors, all the Congressional committees had adjourned forever—and where did that leave him?

Sidelined. Down, in other words. But not out.

Tyler lived alone in a two-story Georgian-style townhouse in Arlington, Virginia. He had equipped the spare bedroom with a formidable array of Nautilus exercise equipment, and in the days after his unproductive conversation with the Chief Executive he spent a great deal of time working out.

Tyler was a month away from his fifty-second birthday, and though he was in fairly good civilian trim, he wanted more: He wanted to be in fighting shape. At his age, it was a difficult proposition. Not that it couldn’t be done. But he was paying for the effort. The token of exchange in this bargain was pain. First the obvious pain of a hard workout, the pain he took to a certain brink and backed away from. Then the stealthy pain that crept up in the night—the aching tendons, the protesting spine, the humiliating discomforts that sent him to the drugstore in search of Ben-Gay, Tylenol, something to help him sleep, something to help him move his bowels.

But there came a time when he was able to look at himself in the full-length bedroom mirror without flinching. Taut chest, lean belly tapering into the waistband of his Jockey shorts, firm legs. Gray stubble hair on his head and a down of gray hair on chest and limbs. It seemed to Tyler that he had created something good here, a reflection he could take some pride in. Appearances had always mattered to Tyler a great deal.

But the important thing was that he was fit for duty.

If anyone could be fit for the kind of duty he had in mind.

* * *

On the second Monday in October he took his old Army jacket out of mothballs, decided he liked the way it looked over a crisp white shirt and dress pants, and climbed into his car and headed for the Marine base at Quantico.

The Virginia countryside was deep in a sweet-tempered autumn. The sky was blue and the full blush of color was on the woods. The highway was mainly empty—as most highways were these days.

Tyler had given a great deal of thought to the crisis facing the country, and he rehearsed his logic as he drove. The problem, he thought once again, was that all the armies had gone home, and how do you engage an enemy without an army?

Guerrilla warfare was the obvious response to an occupying power of superior strength… but you still needed an infantry, a militia, a power base. “The revolutionary moves among the people like a fish in the sea.” Mao Tse-tung. But “the people” had been coopted. The fish was beached. Tyler had seen videotape of African armies, Central American armies, Asian and European and even Israeli and American armies, rabble and trained troops alike, laying down their arms, bailing out of tanks, abandoning trenches and revetments like something from a hippie pipe dream of the sixties. It had happened from Ethiopia to Lebanon, from Turkestan to Latin America, and it had happened without exception.

But it seemed to Tyler that even this defeat could be used to his advantage. Weapons that were rusting in the field couldn’t be turned on an insurgency. He could move among this pacified population, not like a fish in the sea, more like–say—a shark among the minnows or a whale among the kill.

But not by himself. One could be outnumbered. One ought not to be alone.

One in ten thousand, the President had told him.

Tyler didn’t know if that was a reliable statistic. It surely wasn’t an encouraging one. But the military had been a major employer prior to Contact, and even if the situation was as bleak as it seemed, he should be able to find one or two good men.

Maybe he’d waited too long. Maybe the plan he had devised wouldn’t work… but that remained to be seen.

* * *

Quantico was a disappointment.

Last month, the Marine Reservation had been a hive of activity. Local newscasts had shown an apparently endless relay of Hercules transport aircraft buzzing in and out, part of the post-Contact grain airlift to the famine zones of the world.

But that airlift was over now, and the huge USMC complex at Quantico appeared to be deserted. He drove among these brick buildings and overgrown parade fields honking his horn until he grew weary of the echoes rolling back.

He drove to the main gate, stopped his car, and opened the trunk. Sunlight warmed the skin of his neck and dappled the huge statue of the Iwo Jima flagraising. From the trunk, he unwound ten yards of bright orange rip-stop nylon on which he had painted, painstakingly, in letters of waterproof black acrylic, the words:

Any Member of the Aimed Forces Remaining on Duty

Call Colonel John Tyler (202)212-5555

or Report to 731 Portage Street Arlington ASAP

God Bless the USA

He had sewn nylon cords into the fabric at several points, and he attached these to the fenceposts so that the banner hung suspended across the road.

The nylon drooped in the still air, but the message was easy to read.

* * *

Over the course of a week and a half Tyler constructed similar banners and left them at smaller military installations from Baltimore down to Richmond. Every evening, he checked his answering machine for messages. To date: None.

On his trips, Tyler was able to monitor the evolution of the new world. Superficially, not much had changed. Traffic was substantially lighter, especially on the interstates. Tyler saw more people out walking than there used to be, and fewer at work. A lot of small businesses (muffler shops, hairstylists, bookstores) were closed or unattended. People were still running the food stores and shopping at the malls, but he wondered how much longer that would last. Come to that, he wondered how several hundred thousand military and government employees were surviving without paychecks.

The thought was intriguing enough that Tyler tried an experiment. He went into a suburban Arlington grocery store—not in his neighborhood—and filled a cart with canned goods and bottled water. When he came to the checkout he told the clerk, “I don’t have any money. I used to work for HUD.”

He expected security guards. Instead, the clerk—a chubby young redhead wearing a nametag that said “Sally”—smiled and waved him through.

So why was anybody paying? Tyler lingered by the door and took an eyeball survey of the tills. According to his count, it was roughly half and half—half paid, half didn’t. Those who did seemed to be operating mainly by force of habit. Tyler guessed that paying for what you take was a reflex deeply entrenched in the American psyche—not an easy habit to break. It continued regardless, like the Major League playoffs. But he guessed the country was already well on the way to a moneyless economy.

Perfect communism, he thought, as practiced by perfect robots.

Tyler heard a voice inside him say, You’re surrounded by monsters.

It was Sissy’s voice. Sissy was an old, sad ghost. Tyler squared his shoulders and paid no attention. Sissy had been telling him he was surrounded by monsters since the day he was born.

* * *

Over the years, all his memories of Sissy had condensed into a single image. Here was Sissy as she appeared in his dreams: A middle-aged woman in a swaddling of canvas and polyester skirts, two sweaters buttoned over her pillowing breasts, gypsy-bright and red-faced, pushing a wire buggy full of old newspapers on a too-bright city sidewalk.

A bag lady, as they would say nowadays. She was his mother.

His father had been a salesman for a company that sold plastic novelty cups on which the name of a business could be printed in gold flash. The cup Tyler drank from for the first seven years of his life was inscribed with the legend Fletcher’s taxidermy, 33 east fith st, Cincinnati. When Tyler learned to read—he taught himself to read at the age of four years—he discovered the word FIFTH had been misspelled. Which made him cry, for no good reason he could think of. By then, his father was long gone.

His mother (she demanded he call her Sissy) lived in an ancient three-story row house on a hilly street in an urban neighborhood declining toward slum status. She owned the house. Sometime in her younger days, Sissy had inherited money from an aunt in Pittsburgh. Sissy had been young and childless and perhaps, Tyler thought, aware of her own impending dementia. She had bought the row house outright and put the remainder of the money in a trust, which issued her a monthly check.

Tyler’s father had come and gone without gaining access to any of this money. Sissy, a cautious woman by nature, had remained tightfisted even as the world began to slip past comprehension.

Tyler wasn’t sure when he figured out that Sissy was crazy. Probably some other child had been kind enough to let him know. Hey, Tyler, your mothers dressed like Freddy the Freeloader! Hey, Tyler, your house smells like shit!

He learned early on that the best response was a firm and uncompromising Fuck you. It got him beat up a lot. But in the long run, it also got him left alone. And it taught him a valuable lesson about people. You could be afraid of them or you could hate them; those were your choices. Anything else was a trap… a temptation to punishment.

He hated and feared Sissy, but she was also the exception to the rule. Although she was insane, Sissy was still his mother. She fed him, sporadically; she clothed him, eccentrically. She was supposed to care about him, and she was capable of hurting him with her indifference.

He could tolerate the indifference of anyone but Sissy.

That was why, when he went to school for the first time in his life—five days late and in the company of a truant officer—he was driven to tears when everyone laughed at his torn pants, his food-stained shirt.

Not because he cared what they thought. It was Sissy who had wounded him, Sissy who had sent him off so badly dressed.

Sissy, why?

Didn’t she know any better?

Obviously, she didn’t. Sissy had moved into a land where reason and custom had given way to bright strokes of invisible lightning, fearsome revelations too private to share. Sissy, the adult Tyler recognized, had been schizophrenic. Sissy had been defending her home by stockpiling it with garbage and rags, and it was a miracle she had dressed him at all.

Sissy had been dead now for many years. But she visited Tyler regularly and she wasn’t shy about making her opinions known.

* * *

The phone call came while he was watching television. Tyler had installed a satellite dish on the roof and an illegal descrambler in his living room. The descrambler was a neat little sync regenerator based on a CMOS chip and a 3.58 MHz oscillator. He could decode anything, including C-SPAN, HBO, and military broadcasts—not that any of these were on the air anymore.

In fact, since mid-October, there had been only a couple of hours of national TV a day—skeleton CNN broadcasts, mostly coverage of the disarming of the world and the continuous slow unwinding of the octahedrons.

It was this last that interested Tyler. Today, another bright autumn morning, windows open and a breeze tangling the curtains, he sipped a diet soda and watched a videotape of a lone Helper, so-called, gliding along an empty highway near Atlanta.

He was fascinated by the look of it. Seven feet of matte-black formless menace. It was a “Helper” the way Stalin had been “Uncle Joe.”

These curious items had been unwinding steadily from their octahedral bases in New York and Los Angeles, spreading out, forming a network across the country—the world—for purposes unannounced. You can call them Helpers, Tyler thought, but he recognized an occupation force when he saw one.

What would you need to take out one of these dreadnoughts? Well, Tyler thought, let me see… And then, as if in answer, the telephone rang. He stood up from the chair with his heart battering his ribs. Christ! How long since he’d heard that sound?

He had just about given up waiting.

He thumbed the mute button on the remote TV control and snatched up the telephone handset. “Hello?”

It’ll be a wrong number, he thought. Some Contactee who dialed a 5 instead of a 6. Or did they still make such human errors?

“Colonel Tyler?” asked a male voice.

“Speaking,” he managed.

“Saw your sign, sir. Down at Quantico.” Pause. “One of the strings came loose, but I hooked it up again.”

“I thank you for that,” Tyler said. “Are you a Marine?”

Turned out he was, a fairly raw one: a weapons specialist, twenty-one years old. “Name’s A.W. Murdoch.”

“What’s the A for?”

“Alphonse, I’m sorry to say.”

“I’m sorry to hear it. I won’t ask about the W. Do I understand you managed to turn down the invitation to Life Eternal?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, then, we ought to get together.”

“We will. Uh, Colonel Tyler… I take it you’re thinking of offering some resistance here? Meaning no offense, I’m not in need of company for company’s sake. I thought, from your sign, you’d probably want to kick a little ass?”

Eager young buck, Tyler thought. Well, so am I. Eager, at least. “I think that’s a safe assumption. When can I see you?”

“You can see me right now if you step to the window, sir.”

Tyler did so. He peered down from his second-story bay window into the sunny street. Parked there…

…parked on a quiet tree-lined Arlington avenue…

…was a camouflage-brown M998 Hummer, the one-and-three-quarter-ton vehicle that had replaced the Jeep of Tyler’s youth, a sturdy and versatile machine…

… on the roof of which was mounted an M-109 TOW launcher, a tank killer par excellence, looking a little like a ray gun from an old science fiction movie…

… or like an answer to a prayer, Tyler thought…

…and grinning up from the interior of this vehicle was a lanky blond youth whose regulation haircut had grown a little shaggy but whose uniform remained relatively clean, holding in his right hand what appeared to be a cellular phone.

Obviously a smart-ass, Tyler thought, but a smart-ass bearing gifts.

Murdoch saluted, squinting into the sunlight.

“It appears we have a lot to talk about,” Tyler said.

“I’ll be right up, sir.”

“No. I’ll be right down.”

* * *

Tyler had learned how to establish a certain tone in male conversation, a certain rank. In the military, the rules of conduct were explicit. In civilian conversation the matter was more subtle; thus it was important to take command and do so quickly. It was the inability to take command that had frustrated him during his interview with the President, which was still a sore memory. He’d been off balance, at a disadvantage; taking a pistol to the White House was an impulse he should never have obeyed in the first place. It was hasty.

Here, the situation favored Tyler.

A. W. Murdoch was an active Marine Sergeant. John Tyler was a retired Army officer, technically a civilian, a superior officer by courtesy only. But it started well, Tyler thought, when Murdoch addressed him as “sir.” Given that, Tyler thought, all else falls into place.

They sat in the front of the Hummer and swapped stories of the invasion as a prelude to more serious talk.

Murdoch was a California boy, the kind of adolescent drifter that state had so often produced, until he drifted into the Corps and discovered a purpose in life. That purpose was the maintenance of portable weaponry and the instruction of recruits in the use of same, and it was the only thing Murdoch seemed to care much about. When Contact emptied Quantico, Murdoch was devastated. He kept driving back to the base, he said, every few days, like an ant to an empty nest.

Then he saw John Tyler’s sign and guessed there might be a future for him after all.

Tyler offered in exchange some of his own recent history. It was hard to explain the civilian work he’d done, since it crossed so many borders—Congress, the defense industry, banking. His job had been to know people, but not too well; to say things, but not too explicitly. In fact, that life was already beginning to feel vague and distant; the intricacies that had once intrigued and compelled him seemed as abstruse now as the mating dance of an extinct species…

He didn’t say exactly this to Murdoch. He did make some mention of the revolt that had been derailed, at the last minute, by Contact. Murdoch was fascinated: he’d been aware of the high-level alert that August night, the furtive troop movements. “It was exciting,” Murdoch said. “Like something out of the Civil War. Firing on Fort Sumter. I never did care for that windy old fart in the White House.”

Bolstered by this, the Colonel described his last meeting with the Commander in Chief—a somewhat polished version.

Murdoch was wide-eyed. “You actually had a pistol on him?”

“Yes,” Tyler said.

“You could have killed him.”

He nodded.

“Why didn’t you?”

“It wouldn’t have helped. It might have attracted attention. Anyway, he was… too malleable. Too yielding. Do you understand, Mr. Murdoch?”

“I know what you mean. I meet people. People I used to know, even. They’re real nice. Too nice. It’s scary, but you can’t hate ’em for it. Much less shoot ’em. Be like killing a rabbit with a pipe wrench.”

Tyler nodded.

Murdoch extracted two cans of Coors from a cooler in the back of the vehicle. He offered one to Tyler, who popped the tab and listened to the hiss.

“No,” Murdoch said, “they’re not the enemy. Those things on the road, on the other hand…”

“Helpers,” Colonel Tyler said.

“Uh-huh. Now, to me, they look like the enemy.”

“I share your thought,” Tyler said.

“You thought about what to do about it?”

“Obviously. But why don’t you give me your perspective first.”

“Well… there’s all this technology lying around, but most of it you can’t manage if you’re just one person—or just two. Might be fun zooming over the treetops with an A-10 and twelve-hundred rounds of those depleted uranium-tipped slugs, say. But, shit, I’m no pilot. Sir, are you?”

“About a hundred hours in a Piper Cub.”

“We couldn’t even preflight an A-10. So we’re looking at portable ground weapons. Not a tank or a self-propelled Howitzer or anything sluggish like that. I mean, we don’t know for sure what we’re up against. So, something lean. A Dragon, an AT-4. Okay, we can get lots of those. The whole world’s an armory, right? And the doors are wide open. But for a first encounter, I’m thinking power and mobility. I’m thinking shoot and scoot.”

“The Hummer,” Tyler interpreted.

“The Hummer, and more specifically that TOW on the roof. The way I see it, we encounter a Helper on the open road, we can bust it and break away before their cavalry arrives.”

Tyler sipped his beer and pretended to be thinking it over.

“Mr. Murdoch, we don’t know what defenses those things might possess.”

“I don’t think we can find out except by shooting at ’em.”

“Might be dangerous.”

Murdoch heard something in Tyler’s voice, some unsuccessfully suppressed note of mischief. He smiled. “Sir, it might indeed. It’s a pretty day for shooting, though, isn’t it?”

“Don’t get ahead of yourself. You have to teach me how to operate this TOW.” Tyler glanced up at a sky the color of blue chalk. “It’s a pretty day for some live-fire exercises, too.”

Murdoch wasn’t pleased with this. “I’d hoped to operate the TOW myself—you know—when it comes time.”

“Rank has its privileges, Mr. Murdoch. I expect we’ll both get a chance.”

“Yes, sir,” Murdoch said.

* * *

They came to know each other that first week they were together on the live-fire range at Quantico, Murdoch teaching him the TOW and some smaller tank-killers. Tyler guessed you could say they were friends, the barrier of command fractured a little by their odd situation. Tyler shared some secrets, as friends do. But there were secrets he simply couldn’t share, had never shared with anyone—such as the history of his madness.

“Madness,” too strong a word, but Tyler used it to remind himself that it was not merely unhappiness, not merely self-pity, it was a darker and more powerful presence that from time to time settled upon him.

Ever since Sissy died.

These memories came back at night.

Key events during his twelfth year: He achieved a B+ average at school, scored well above the norm on a Stanford-Binet intelligence test administered by the school board, and fainted twice, once in gym, once in homeroom. The school nurse asked him what he usually ate for breakfast and dinner, and he answered, both times, “Frosted Flakes.” He liked the picture of the tiger on the box. He did most of the shopping himself. He never bought vegetables because he wasn’t sure how: you put them in these plastic bags, you weighed them… it was confusing; he worried he might spend more than the three or four dollars Sissy let him carry to the store.

As for canned vegetables—he had tried that once. Canned peas, which came out pale green and wrinkly, not much like the picture on the label. Sissy said they tasted like rat poison. Had he ever watched a poisoned rat die? Sissy had. Sissy described the event. “You want to do that to me?”

Tyler thought he’d better stick to Frosted Flakes.

The nurse and his homeroom teacher conferred, which led to a visit from a social worker, which led, after no little trauma, to Tyler’s installation in a foster home and Sissy’s forcible remittance to a white brick building out of town, where she died six months later of “an accident while bathing.” Tyler had seen the guards who worked at this institution: They were barrel-chested, stupid, and permanently pissed off. Sissy used to spit at them. So Tyler was suspicious when they told him the “accident” part. But Sissy was dead—that was a fact.

He never found out what happened to the old row house or Sissy’s remittance money. He didn’t want to have anything to do with either one. He was glad Sissy was gone. Life was better without Sissy.

Still, when he overheard a social worker say the same thing—that he would be better off without Sissy– Tyler tried to kill the woman with the sharp end of a blue Bic pen.

He didn’t do much more than scratch her face, though he privately hoped the ink had dyed the skin beneath the wound, a permanent tattoo, a reminder that such calculations were not hers to make.

The act propelled him out of his foster home and into a grim institution (perhaps not unlike the white brick building in which Sissy had died spitting at her captors) in which Tyler was kicked, assaulted, humiliated, sometimes brutalized, at best ignored. He was rescued from this limbo when a legal inquiry into Sissy’s holdings discovered a living relative who was willing to take custody of the boy.