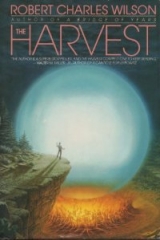

Текст книги "The Harvest"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Chapter 26

Election

Beth Porter shook the boy’s hand and gazed a moment at his wide blue eyes.

They were strange eyes for a kid that age, Beth thought. Too… something. Calm? Calm but observant.

But he seemed like a nice-enough kid. People seemed to enjoy seeing a new face. Everybody shook William’s hand and made welcome noises at him. Even Colonel Tyler bent and ruffled the boy’s hair—though William’s smile at that moment looked suddenly less genuine. And that was odd, too, Beth thought.

Then Matt Wheeler called the meeting to order.

They had gathered in the living room of a little wood-frame house next to a gas station. The house was dusty and stale from being closed up so long, but cozy enough on a chilly spring night. Matt had brought in ten folding chairs from his camper. Tom Kindle had plugged in an electric heater, which was minimal help, but what really mattered, Beth thought, was that they had come over the Cascades into the Land of the Functioning Wall Sockets. She guessed it was some Helper voodoo that kept the electricity working in all these derelict towns… as in Buchanan before the storm trashed everything. She didn’t care. Lights that didn’t need batteries: heaven. Hot water: bliss.

This very afternoon they had broken into the house and taken turns under a working shower. Beth recalled that first amazing flourish of steamy water on the skin of her back. It was like the caress of some fiery angel. She’d been savoring the memory for hours.

She settled into a folding chair next to Abby Cushman, a row behind Joey. Up front, with the room’s two sixty-watt floor lamps making him look pale and skinny, Matt Wheeler zipped through some old business, chiefly the news that Joey had scavenged a portable ham rig in Twin Falls, plus a quick unanimous “aye” on the proposition to continue east first thing tomorrow.

Then it was time for the serious vote of the evening… the one Beth had been dreading.

Matt looked tired when he announced it. “Last week we resolved to open the position of Chairman to an election. We can start with nominations—anyone?”

Joey jumped up, almost knocked his chair into Beth’s knees. “I nominate Colonel John Tyler!”

“Seconded,” Jacopetti said.

Well—that was quick, Beth thought.

Abby Cushman, looking a little startled, put her hand up. “Matt, you’ve been doing a fine job. Can’t we just carry on? I nominate you.” Now it was Miriam who seconded. Another surprise. “Two candidates,” Matt said. “Anyone else?” Jacopetti said, “Isn’t two enough? Why don’t we all run?” No more.

“Okay,” Matt said. “Do we need debate on this? I think everyone knows where the Colonel and I stand.” Conceded.

“We’ll vote by show of hands. Colonel Tyler and I will abstain—and maybe our new resident should, too, at least until he’s more familiar with current events.”

Miriam smiled. “I’m sure that’s all right with William.”

“Good. Show of hands for Colonel Tyler?”

Beth looked around hastily. Joey’s hand shot up, of course. Jacopetti’s, in a gesture that was somehow smug. Two, Beth thought. Two out of nine.

Bob Ganish offered a plump hand. Three.

There was a long, tense moment. Nothing.

“Hands for yours truly?”

Abby’s, at once, and Tom Kindle’s; then Miriam’s hand went up. Three versus three, Beth thought. Abby said, “In the event of a tie?”

“Ordinarily,” Matt said, “the Chair would cast the deciding vote… but that’s hardly fair, since both Colonel Tyler and I agreed to abstain. There’s probably something in the Rules of Order. Maybe it would be simpler just to try it again—we had a lot of abstentions. Maybe some of those folks will change their minds.”

Meaning me. Beth found herself blushing. Me and Chuck Makepeace and Tim Belanger.

Makepeace she couldn’t predict. As for Belanger… Matt had saved the guy’s life, dragging him down a hospital corridor during the storm. But Belanger had been pretty close to Tyler ever since the Colonel arrived. And this was only a chairmanship vote, after all, not a test of loyalty… or at least that was all it seemed to be.

Makepeace, Belanger…

And me, Beth thought. Please God, don’t let it come down to me. “Hands for Colonel Tyler?”

The same three: Joey, Jacopetti, Bob Ganish… and now, uh-oh, Beth thought, a fourth—Chuck Makepeace had slid into the Tyler camp. “Could still be a tie,” Abby commented. “No cheerleading,” Matt said. “For yours truly?” Miriam, Abby, Tom Kindle. Beth folded her hands in her lap and stared at them. When she looked up, Belanger had raised his hand for Matt. Four to four.

Jacopetti turned to her. “Time to shit or get off the pot, m’dear.”

She thought about Matt: weary, unhappy at the front of the room.

She thought about Colonel Tyler. The way he shook her hand one time. The way he smiled.

She couldn’t bring herself to look at either candidate. Or at Joey. Or Jacopetti, the toothless SOB. “Tyler” she said, a whisper.

Jacopetti: “Pardon me?”

She gave him a hateful stare. “Colonel Tyler!”

There was a silence in the room.

Joey turned, offered an evil grin.

Matt cleared his throat. “Colonel?”

Tyler stood up, immaculate in his uniform. “Yes, Dr. Wheeler?”

“I believe this is your gavel now.”

* * *

Beth remembered when Colonel Tyler came to town. It was in that desperate time when the storm had passed, when Beth had climbed out of the rubble into a world of no landmarks—a world of everything flat and broken, where you might find a bedframe nestled in the hollow shell of a Volkswagen, or a pleasure boat riding on a sea of windfall pines.

After a few days, Beth had been assigned to the food search. With Abby Cushman and Bob Ganish, she had hiked south on the highway—which was not even a road anymore, barely a trail among the scattered detritus of ruined buildings—to the place where the big A P had stood. Just finding it was an act of archaeology. Beth had always navigated by the man-made markers, road signs and intersections and malls. Now there was nothing except the curve of the bay, the cryptic angle of Mt. Buchanan above a plain of homogeneous junk.

The storm had left chalk-blue skies and a chill wind behind it. Beth was cold in a ragged sweater, soon dirty from prying up soggy drywall and ancient lathing, hunting for canned food, which they loaded into big double-ply garbage bags for the trip back into town. She felt like something medieval. A ragged, scrounging peasant.

Mid-afternoon, her nose running from the chill, she stood up straight to ease the ache in her back; and that was when she saw him.

Colonel John Tyler.

She knew immediately who that distant figure was. Joey had talked to him on the radio. More recently, Chuck Makepeace had announced that the Colonel was on his way to Buchanan. But that was before the storm. Beth thought the storm must have changed everything—all plans had been erased.

But Colonel Tyler had arrived as promised.

He was on foot. He was a little dusty. But he came along the ruin of the highway with his head high, face clean-shaven, his Army jacket threadbare but neat, and Beth felt a voiceless rush of pleasure at the sight of him—ghost of a world that had seemed so lost.

She didn’t tell the others. Let them scrounge in the ruins while Beth watched this man come closer. She wished her face was less dirty, her hair not so tangled.

Then Abby straightened and caught sight of him.

“Well, gosh,” she said.

Bob Ganish stood with a green garbage bag in one hand, mouth open and his belly spilling over his belt. Some welcoming committee, Beth thought. A middle-aged lady, a grimy ex-car dealer. Me.

Tyler smiled as he approached. You could see his age. He wasn’t young. But he was in good shape. His gray hair was cut close to his skull. He looked like he wasn’t tired. He looked like he could walk forever.

Beth, suddenly embarrassed, plucked at the hem of her ratty sweater.

Ganish stepped forward and introduced himself. Colonel Tyler shook hands solemnly. “We talked once on the radio,” he said: a resonant, calm voice. “Nice to meet you in person.” And Abby. “Heard a lot about you, Mrs. Cushman.”

Smiles and breathless welcome-stranger bullshit. Then they introduced Beth.

Colonel Tyler shook her hand.

His hand was big and warm. Her own hand was cold from the weather, raw from the work. She was grateful for the touch. She thought his hand was one of the most interesting things she had ever seen—a big man’s hand, creased and hard, but gentle.

“Prettiest face I’ve encountered in a long time,” Tyler said, “if you don’t mind me saying so, Miss Porter.”

“Beth,” she managed.

“Beth.”

She liked the way it sounded when he said it.

Then they all hiked back into town, Tyler sharing the weight of the canned food, and he talked a little about how bad the roads had been, “but it’s a different story over the mountains,” and how they would have to take their time, plan for the journey east, and so on and so forth, Beth not speaking or really listening much; and then all the others had to meet Tyler, show him the shelter they’d made of the intact corner of the hospital basement; and Joey was beside himself, glowing whenever Tyler talked to him, which was often, since Tyler and Joey had become good radio buddies. Then there was planning to do, Tyler conferring with Matt and Tom Kindle mainly, and the days had run in a busy torrent ever since.

But she remembered the touch of his hand.

Prettiest face I’ve seen in a long time.

Beth had passed her twenty-first birthday on the road out of Oregon. She didn’t mention it; no one knew. But it got her thinking. Maybe she’d been acting like a teenager well past her due date—riding around on Joey’s motorcycle committing penny-ante vandalism. But she was twenty-one years old; she was a woman; maybe not the world’s most attractive or well-bred specimen, but the only woman under forty among the local survivors. A fact that made Joey paranoid (not that he had any right to be) and everyone else a little nervous. Chuck Makepeace had made a couple of very tentative passes; so, even more tentatively, had Tim Belanger.

But they didn’t attract her.

Who did?

Well… Joey had, once, but that was over. An aspect of her life she didn’t much care to recall.

Matt Wheeler attracted her.

Colonel Tyler attracted her.

None of this was very surprising. What was new was the idea that she might attract them. And maybe (and here was the real novelty), maybe not just because she was the only game in town.

Since Matt, since her experience with Jacopetti in the hospital basement, Beth had been exploring a new idea—the idea that she might have some work of her own to do in this new world.

Something more significant than clerking at a 7-Eleven.

A new world, new work, a new Beth Porter coming up through the rubble.

Which reminded her of the tattoo on her shoulder.

WORTHLESS

It had seemed like a good idea at the time.

Maybe it had been.

Maybe it had been true.

Maybe it wasn’t anymore.

* * *

She would have to explain to Matt about the vote. Not something she looked forward to.

For now, she watched Colonel Tyler at the front of the room. He smiled, thanked Matt for everything he’d done, thanked everybody for demonstrating their confidence in a relative newcomer. He said he took the chairmanship seriously and he’d do his best to live up to their expectations.

Then he looked at his watch. “It’s late and I guess we all want to get some sleep before we move on in the morning. So just a little bit of business here. Some people have been complaining about the weekly meetings. We see each other every day, maybe there’s no reason to have a formal assembly so often when there’s no special business pending. Seems reasonable. I think we can safely schedule full Committee meetings at a rate of once a month, and I’ll ask your consent for that—unless there’s any objections?”

No objections, though Matt was frowning massively.

“Okay,” Tyler said. “Some picayune items… I’ve posted a watch tonight, and I think we should make that a permanent fixture. Joseph and Tim volunteered for duty. They can be our regular standing guard as far as I’m concerned—until they get tired of it, and unless anybody has a reason why not.”

Kindle said, “We’re talking armed guards here?”

“Handguns,” Tyler said.

Abby: “Is that necessary, Colonel?”

Tyler smiled his gentle smile. “I hope it isn’t, Mrs. Cushman. I trust it won’t be. But we’d be stupid to take an unnecessary risk. There’s always the possibility of wild animals, if nothing else. I won’t ask a man to sit alone all night without some form of protection.”

(“Holy crow,” Kindle said softly.)

And more such items, none offered for a vote, but the Colonel pausing briefly for “objections,” which never came. It was businesslike, Beth thought. A little dizzying, however.

There was something about the radio: Makepeace and Joey were a joint committee and controlled access. Communication with Helpers—there was a Helper in every one of these microscopic towns—would be strictly through a designated representative: Tim Belanger. “Helper communication should be kept to a minimum, in my opinion, since we’ve all suffered at the hands of the Travellers, and I’m not sure we should place absolute trust in their emissaries, though I’ll be the first to admit they’ve been useful from time to time.”

Finally a motion to adjourn. Hands shot up. Kindle whistled appreciatively from the back row. “Fast work, Colonel.” Tyler looked mildly irritated. “You can voice your dissent at any time, Mr. Kindle. That’s what this forum is all about. However, we’re adjourned.”

“We sure are,” Kindle said.

* * *

Matt had picked up some material for Beth at a local lending library—a Red Cross first-aid handbook with a chapter on traumatic injuries, which he had annotated in the margin where it was out of date. In a couple of weeks, he wanted her familiar with the use of a hypodermic needle and a range of common antibiotics. The problems they were most likely to be looking at, aside from Jacopetti’s coronary trouble and Miriam’s geriatric complaints, were injuries and bad food. He had scheduled a session with her tonight.

But the meeting had run late… she might not show up.

Might not want to, Matt thought. It was cold in his RV. A lot of people were sleeping indoors tonight. Kindle had been warning people about turning on long-disused oil furnaces ever since they passed that burned-out section of Twin Falls, and gas furnaces weren’t working anymore, anywhere, for no known reason. But the Travellers had been scrupulous about electricity. Kindle had hooked up expensive space heaters, the kind with gravity switches to turn off the juice if somebody knocked the thing over. Heat a room, let people camp in it. It was reasonably safe and it took the chill off some arthritic bones, including Miriam’s.

But Matt preferred his camper. He had converted the RV into a combination of home and consulting office. It provided a little continuity in a world that had turned so many things so completely upside-down.

He picked up another library book, a Raymond Chandler mystery, its urban setting so distant in time and circumstance that it felt like science fiction. And he switched on a battery light and settled down.

The wind came briskly along the dry margins of the Snake River and rocked the RV on its old, loose shocks. Matt found his attention drifting: from the book to Tyler, the election, the boy who had wandered into camp this afternoon…

He was yawning when Beth knocked.

She let herself in. Matt checked his watch. “Beth, it’s late—”

“I know. Everybody’s asleep.” She hesitated. “I came to explain.”

About the election, she obviously meant. Explain, Matt noted. Not apologize. “It’s all right,” he said.

“No.” She frowned. “It’s not all right. I don’t want to leave it hanging. Matt, it’s not that I don’t trust you or you haven’t done a good job. Everybody knows you have. But when you were standing up there, it just seemed like… you just looked so fucking tired.”

Had he? Well, maybe. Was he tired?

More than he dared admit.

She said, “It might have been the wrong thing to do.”

“You did what seemed right at the time. That’s all anybody can ask.”

“It just seemed like you didn’t really want the job.”

“I didn’t.”

“But you don’t want Colonel Tyler to have it.”

“Well—no.”

“He doesn’t seem like a bad person.”

“That’s not the issue. He didn’t just take over the Committee, Beth, he bulldozed it. Ten minutes of Colonel Tyler, and what do we have? Restricted access to Helpers. Restricted access to the radio. The camp under an armed guard.”

Beth looked uneasy. “You make it sound sinister.”

“It is sinister.”

“I think he’s just used to the military way of doing things.”

Colonel Tyler, by his own testimony, had left the military almost fifteen years ago. It wasn’t force of habit that had put him in charge tonight. It was careful planning, Matt thought, and a couple of partisan malcontents: Paul Jacopetti and Joey Commoner.

And something else. Matt sensed in the Colonel a certain restlessness, an impatience that always seemed about to break out into violence. Catch him in a quiet moment and you’d find Tyler tapping his foot to some inner rhythm, his eyes fixed and absent and his big hands closed into fists.

But he couldn’t say this to Beth without sounding paranoid or petty. Anyway, her vote hadn’t mattered any more than Chuck Makepeace’s vote, or Bob Ganish’s. It was only bad timing that made it seem that way.

She had done what she thought was the right thing, and in the end maybe her call was as good as his.

She said, “I guess I should leave.”

“Only if you want to.”

Tentatively: “You’re not angry?”

“No.” He realized he wasn’t.

She sat beside him. Relieved, weary, she put her head against him.

He stroked her long hair and listened to the night wind tugging at the corners of the RV. He would never get used to these inland plains. He missed the sea.

He thought about Beth—all the aspects of Beth Porter. The neglected, sullen Beth: the Beth who had tattooed WORTHLESS on her shoulder, who had baited Joey Commoner until Joey felt compelled to pull a knife.

And this other Beth. Beth treating Jacopem’s anxiety with the anodyne of her own calm. Beth studying anatomy textbooks with the dedication of a monk.

Something clean and strong rising out of all the garbage in her life. “Joey’s standing watch,” she said. “He has a campfire on the highway facing west.”

“Did he see you come?”

“No. Anyway, I’m tired of worrying about Joey. He’s acting like an asshole.”

“Maybe a dangerous one.”

“Joey and his pocketknife? I doubt it.”

“After what you said that night…”

“I shouldn’t have. I know. But he doesn’t own me. He never did.”

“We’re a fragile community. I don’t want to create one more problem.”

“Then should I leave?” Challenging him. “Beth—you know you don’t have to.”

“I want to stay a while longer.”

“Then stay.”

A cold night. A little warmth.

Chapter 27

Destinations

The caravan of ten dusty RVs and trailers, led by Colonel Tyler in a four-wheel-drive Ford pickup, turned south on Interstate 84 toward Utah.

Tyler drove with the windows rolled down, admitting a breeze so dry it made his lips bleed. He drove at a cautious, steady pace. Sometimes he felt fettered by the train of ponderous vehicles behind him. But it was a privilege, he thought, to blaze the trail. To see the way ahead.

The highway seemed wider for being empty. Periodically he passed an abandoned truck or car, and it was nice to know that in an emergency the Committee could siphon gas from one of these. But no emergency arose. Most of the roadside gas stations had functional pumps, and Joey Commoner and Bob Ganish had been scrupulous about keeping the convoy’s engines in decent repair.

Tyler led them across the Great Basin into Utah, joined what had once been a populous stretch of 1-15 north of Brigham City, then veered east on 1-80 where the towns grew sparse again.

Tyler read the road maps with great care. He was worried about crossing the Rockies. 1-80 skirted much of the mountains, followed the Union Pacific route through the Red Desert in Wyoming, but late or early storms had been known to strand unwary travellers.

He called a halt at a town named Emory and pressed on in the morning. The sky when he started his engine was bright with herringbone clouds.

The road climbed and subsided and began to climb again.

He felt better when the road wound away from civilization. Those empty towns were oppressive. Mountain and desert were simply eternal. Granite and sagebrush and cheat grass: invulnerable to all the discord that had dropped like bad magic out of a starry sky.

He was alone in the cab of the pickup truck, although Sissy kept him company.

* * *

Sissy had been keeping him sporadic company since that town in Georgia—Loftus.

She spoke to him, a voice out of the wind, but he didn’t actually see her until one afternoon in rural Texas while he was driving the Hummer west. It seemed appropriate that Sissy should appear in the desert. The desert was a place of mirages, dust-devils, chromium-blue lakes shimmering where the highway touched the horizon. Sissy had seemed exactly that tenuous, sitting next to him where A.W. Murdoch used to be. She was a translucent, desert-dry Sissy—dressed as inappropriately as ever in cotton and nylon and polyester of all colors, clothes so brittle with old dirt that any motion emitted a greasy rustle and exuded an odor too stale to be offensive. It was the smell, Tyler thought, of something dead that had dried a long time in the sunlight.

The radio was good, Sissy told him, good to be talking to those people, smart, but be careful, she said: stay away from the crowds, all those East Coast city survivors, clever and dangerous in some way she never explained. Talk to that Joseph, Sissy said. He admires you.

Sissy was an illusion. Tyler knew that. Of course he did. You’d have to be crazy to believe she was really sitting there, some kind of ghost.

She was, as the psychologists would no doubt say, a private revenant, a fragment of himself. She was Tyler giving Tyler Tyler’s advice.

But in another way she really was Sissy: Sissy cut loose from memory. His memory had lost its grip on Sissy the way a child might lose its grip on a balloon; and like a balloon she had risen up, had floated out of his head and come to rest in the passenger seat beside him.

Sissy advised him to drive to Oregon, hike down from the coastal mountains to Buchanan, assume a leadership position among these ragged refugees.

Lead them east, Sissy said.

To the gathering place of the survivors, a new home in the valley of the Ohio River, a sheltered place—or so Tyler told them, and it had even seemed true for a while.

But Sissy—always a repository of unpleasant surprises—had been coy about their destination.

Tyler led his caravan up a road walled with granite, threading a path around fallen rock. Whenever he turned his head to the right he found Sissy gazing at him. Today she was bright as the sun, her plump cheeks a blazing white, difficult to look at.

Those people back east, Sissy said. They surrounded themselves with Helpers. They talk to Helpers.

“True,” Tyler said.

Helpers are the voice of that thing in the sky… “I know,” Tyler said, weary of these cryptic pronouncements. Sissy’s eyes, volatile and relentless, demanded answers he was helpless to produce… and of the dead. “Dead what?” The skinless living.

The Contactees, Tyler interpreted. Contactees who had died might be able to speak through the Helpers. The dead might talk to the living. Tyler said, “The danger…”

They’ll talk about you, John. That girl you killed in Loftus. Maybe it will be Murdoch talking. Maybe Murdoch crossed over, too. And who else might talk? They might talk about Stuttgart. They might remember every sin you ever committed.

This was a new and unwelcome idea.

People will know what you are.

Peevishly: “I’m no worse than the rest.”

They’ll know about Loftus. They’ll call you killer.

Would they? Extraordinary circumstances, Tyler thought. Alien possession. The girl had been… not human.

Anyway, he told himself, I’m a man of some stature. A man who served his country, a man who made a place for himself in the business world. A man who had once been a familiar presence in the Capitol Building, a man accustomed to lunching with Defense Department functionaries or the members of oversight committees. Above certain kinds of innuendo.

That’s a joke, Sissy said. Another Washington crook. What’s the difference?

Tyler worked at remembering that period of his life. It had been structured, formal, complex. In those days he had known how to seal off this Sissy part of himself. Compartment A: The presentable Colonel Tyler. Compartment B: Certain phantoms. Certain urges.

But with Contact, the borders had grown tenuous. Like a naval vessel, he thought. Bulkheads breached. Flooding in the engine room. Fire in the hold.

The sad fact was, he talked to this ghost because he had no choice. Pay attention, Sissy scolded him. To…?

The danger! You can’t risk being exposed.

But even Colonel Tyler had dreamed of that green valley in Ohio. A gathering place, a new life—safety. A trap, Sissy said.

“But if not there,” Tyler said aloud, “if that’s not where we’re going…”

But when he turned to pose the question, Sissy had vanished.

* * *

They came across a fallen telephone pole blocking the highway. Tyler called a halt, then enlisted Joey Commoner and Chuck Makepeace to work a chain around the pole and hook it to the rear of the pickup.

Tyler revved the Ford’s heavy-duty engine, inching forward against the drag. The pole gave a moan of stressed timber and then began to shift.

Tyler took careful note of the people who had climbed out of their campers and RVs to drink bottled soda and watch the show.

Kindle and Wheeler stood together, both poker-faced. Wheeler in particular seemed to be working to disguise some emotion. His resentment, Tyler supposed, at being elbowed out of the leadership position.

Among the rest Tyler identified idle curiosity, some cautious frowns from the likes of Abby Cushman and Miriam Flett, frank idolatry from Joey Commoner.

He turned away to measure his progress, and when he looked again he was surprised to see Sissy among the crowd—a more ethereal presence.

A dry wind came rivering down this pass, but Sissy’s long, tangled hair hung limply over her shoulders; her layered clothes stirred not at all.

She extended her hand over the head of the new boy, William.

This one, Sissy said. Her lips moved soundlessly, but Tyler heard the words as if they were his own. Watch out for this one.

He drove until sunset.

* * *

“A lot of settlers came through here,” Kindle said. “Mormons, especially, but also people on the Oregon Trail, the California Trail. You can still find their wagon tracks on the scrub prairie about forty miles north.”

Matt walked with his friend along the highway away from camp.

They had stopped for the night along a stretch of high Wyoming rock desert that seemed to Matt infinitely dry, silent, and immense. Dinner was over now and the watch fires had been lit.

“Matthew,” Kindle had said, “let’s walk a bit. Get the kinks out.” And Matt understood that the older man had something difficult to tell him.

Neither moon nor Artifact had risen and the stars were bright in a cold sky. When he spoke, Kindle’s voice seemed to hover in the air.

“It was called the South Pass,” Kindle said. “You followed the North Platte to the Sweetwater, Sweetwater to Pacific Creek, Sandy Creek, the Green River Crossing. The Overland Stage Route came through that way. Pony Express.”

Scuff of shoes on empty road. Matt said, “Sounds like you know the territory.”

“Lived two years up in the Wind River Range. Did a lot of hiking through Whiskey Mountain and Popo Agie. Beautiful country.”

“You miss it?”

“Been thinkin’ about it a lot.”

They approached the small fire where Joey Commoner was keeping watch. Joey stood up at the sound of footsteps, turned to face them with his hand hovering at the pistol Colonel Tyler had supplied him.

“Halt,” Joey said, his voice cracking.

Kindle yawned and regarded the boy. “Joey, if you ever aim a loaded pistol in my direction I’ll feed it to you—fair warning.”

“The Colonel doesn’t like people outside camp perimeter at night.”

“I don’t suppose he does. I don’t suppose he likes my shirttail untucked, either, but he’ll have to put up with it, won’t he?”

“You go on report if you’re out of bounds.”

“Fine,” Kindle said. “Maybe later the Colonel can slap my wrist.”

“You’re such a shithead,” Joey said.

Kindle looked at him a long moment—sadly, Matt thought. Then they walked on, past the fire, past Joey.

Matt tried to imagine crossing this blank immensity in a covered wagon. No highways, no gas stations, no motels. No Helpers. The stars sharp as needles.

“Matthew… can you believe this bullshit? Pass a checkpoint before we can take a walk?”

He shrugged. “Joey’s just—”

“Joey isn’t ‘just’ anything. Joey’s following orders and loving every minute of it. We’re not living in a town anymore, we’re living in a barracks. That’s why—”

Kindle hesitated. Matt said, “Why what?”

“That’s why I’m leaving.”

No. “You can’t.”

Kindle was a shadow in the starlight, large and gray. “Matthew—”

“Christ, Tom, I know what’s going on as well as you do. Tyler did his little putsch, and now we have to live with it. It’s painful. But we’re still moving. Heading for a place where Tyler will be one small frog in a big pond. They’re holding real elections in Ohio. According to the radio—”

“When’s the last time you heard the radio? The Colonel’s got it locked up.”

“Beside the point. In Ohio, the Colonel won’t matter.”

“Don’t underestimate the man.”

“The bottom line,” Matt said, “is that we’re more likely to get there if you’re with us.”

“The bottom line is that it’s not my job.” Kindle selected a pebble and threw it into the darkness, an invisible trajectory. “Anyway—I never wanted to live in Ohio. Tell you a story. Once upon a time I hiked along the Titcomb Valley, that’s up in the Wind River Range. I was thirty-three years of age, and I thought that was pretty damn old. East side of the valley is Fremont Peak. North is Mount Sacajawea. At the head of the valley is Gannett Peak, highest in Wyoming. All well above the timberline. Glaciers on those mountains like blue rivers of ice. So pretty it hurts. I camped there a night. When I left, I promised myself I’d come back, one way or another, before I died. See all this a second time. I never got around to it.”