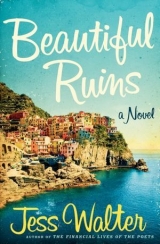

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

4

The Smile of Heaven

April 1945

Near La Spezia, Italy

By Alvis Bender

Then spring came, and with it, the end of my war. The generals with their grease pencils had invited too many soldiers and they needed something for us to do and so we marched over every last inch of Italy. All that spring we marched, through the chalky coastal flats below the Apennines, and once the way was cleared, up pocked green foothills toward Genoa, into villages crumbled like old cheese, cellars spitting forth grubby thin Italians. Such a horrible formality, the end of a war. We groused at abandoned foxholes and bunkers. We acted for one another’s sake as if we wanted a fight. But we secretly rejoiced that the Germans were pulling back faster than we could march, along that wilting front, the Linea Gotica.

I should have been pleased merely to be alive, but I was in the deepest misery of my war, afraid and alone and keenly aware of the barbarism around me. But my real trouble was below me: my feet had turned. My wet, red, sick hooves, my infected, sore feet, had gone over to the other side, traitors to the cause. Before my feet mutinied, I thought primarily about three things during my war: sex, food, and death, and I thought about these every moment that we marched. But by spring, my fantasies had given way entirely to dreams of dry socks. I coveted dry socks. I lusted, pined, hallucinated that after the war I would find myself a nice fat pair of socks and slide my sick feet into them, that I would die an old man with old dry feet.

Each morning, the grease pencil generals caused artillery waves to crash to the north as we marched in our sodden rain gear into a slashing, insistent drizzle. We moved two days behind the forward combat units of the Ninety-second, the Negro Buffalo Soldiers, and two battalions of Japanese Nisei from the internment camps, hard men brought in by the grease pencils to do the heavy fighting on the western edge of the Gothic Line. We were goldbricks, mop-ups, arriving hours or days after the Negro and Japanese soldiers had opened the way, happy beneficiaries of the generals’ crude biases. Ours was a recon/intel unit, trained specialists: engineers, carpenters, burial detail, and Italian translators like me and my good friend, Richards. Our marching orders were to come in behind the forward units to the edges of overrun and destroyed villages, help bury the bodies, and hand out candy and smokes in exchange for information from whatever frightened old women and children were left. We were meant to gather from these wraiths intelligence about the fleeing Germans: placement of mines, locations of troops, storage of armaments. Only recently had the grease pencils asked that we also record the names of men who’d escaped the Fascists to fight alongside us, the Communist partisan units in the hills.

“So it’s to be the Communists next,” grumbled Richards, whose Italian mother had taught him the language as a boy and thus saved him from heavy combat years later. “Why can’t they let us finish this war before they start planning the next one?”

Richards and I were older than our platoon-mates, he a twenty-three-year-old two-stripe, me a twenty-two-year-old PFC, both of us with some college. In neither appearance nor manner could anyone tell Richards and me apart: I a lanky towhead from Wisconsin, part-owner of my father’s automobile dealership, he a lanky towhead from Cedar Falls, Iowa, part-owner with his brothers of an insurance firm. But while I had back home only a string of old girlfriends, a job offer to teach English, and a couple of fat nephews, Richards had a loving wife and son eager to see him again.

In 1944 Italy, no piece of intel was too small for Richards and me. We reported how many loaves of bread the Germans had requisitioned and which blankets the partisans had taken, and I wrote two paragraphs about a poor German soldier with impacted bowels cured by an old witch’s palliative of olive oil and ground bonemeal. As dreary as these duties were, we worked hard at them because the alternative was liming and burying corpses.

Clearly, there were larger tactics at play in my war’s end (we heard rumors of nightmare camps and of the grease pencils dividing the world in half), but for Richards and me, our war consisted of wet, fretful marches up dirt roads and down hillsides to the edges of bombed-out villages, short bursts of interrogating dead-eyed dirty peasants who begged us for food. The clouds had come in November, and now it was March and it felt like one long rain. We marched that March for the sake of marching, not for any tactical reason, but because a wet army not marching begins to smell like a camp of hobos. The bottom two-thirds of Italy was liberated by then, if by liberated one means ground over by armies that chose only to shell the most beautiful buildings, monuments and churches, as if architecture were the true enemy. Soon the North would be a liberated rubble heap as well. We marched up that boot like a woman rolling up a stocking.

It was during one of these routine sorties that I began to imagine shooting myself. And it was while debating where to put the bullet that I met the girl.

We had hiked up some donkey highway, two tracks in the weeds, villages appearing at the tops of knolls and the bottoms of draws, hungry bug-eyed old women slumped alongside roads, children peering from windows of broken houses like modernist portraits, framed by cracked sashes, waving gray fabric, holding out their hands for chocolate: “Dolcie, per favore. Sweeeets, Amer-ee-can?”

A gravel tide had washed over these villages, smashing everything once coming in, again going out. At night we camped on the outskirts of these rutted burgs, in leaning barns, in the carcasses of abandoned farmhouses, in the ruins of old empires. Before crawling in my mummy bag each night, I eased out of my boots, took off my socks and swore at them, pleaded with them and hung them in desperation from a fence post, a windowsill or tent strut. Every morning I woke with great optimism, put these dry socks on my dry feet, and some chemical reaction ensued, turning my feet into moist, larval creatures that fed on my blood and bone. Our supply sergeant, an empathetic, fine-boned young man who Richards believed had his eye on me (“You know what?” I told Richards, “If he can fix my feet I’ll blow taps on his yacker”), was constantly getting me new pairs of socks and foot powders, but the traitorous creatures always found their way back in. Each morning I sprinkled powder in my boots, put on new dry socks, felt better, took a step, and found rapacious leeches feeding on my toes. They were going to kill me unless I acted soon.

On the day I met the girl, I had finally had enough and gotten the nerve to act: AD, accidental discharge, right through one of my rebellious hooves. I would be sent home to Madison to live with my parents, a footless invalid listening to Cubs games on the radio and telling my nephews an ever-improving story of how I lost my foot (I stepped on a land mine, saving my platoon-mates).

That day we were to march to a newly liberated village to interview survivors (“Cand-ee, Amer-ee-can! Dolcie, per favore!”), to ask the peasants to rat out their Communist grandsons, to inquire as to whether the routed Germans might have happened to mention, as they ran away, oh, say, where Hitler was hiding. As we marched toward this little hill town, we passed, just off the road, the rotting body of a German soldier draped over some kind of rough, half-finished sawhorse made of gnarled tree limbs.

This is mostly what we saw of Germans that spring, corpses previously taken out by hardened soldiers or even harder partisans, whose work we superstitiously respected. Not that we were simply tourists ourselves; we’d seen a bit of action. Yes, dear dull nephews, your uncle had issue upon which to fire his .30 caliber in the enemy’s direction, little puffs of dirt exploding at the end of my every shot. It’s difficult to know how many clods of dirt I hit, but suffice it to say I was deadly to the stuff, dirt’s worst enemy. Oh, and we took a bit of fire, too. Earlier that spring we lost two men when German 88-mm cannons hailed the road to Seravezza and three more in a horrific nine-second firefight outside Strettoia. But these were exceptions, frightened bursts of adrenaline-blinding fear. Certainly, I saw valor and heard other soldiers testify to it, but in my war combat was something we tended to come across after the fact, grim puzzles like this one, left as brutal tests of illogic. (Was the German building a sawhorse when his throat was cut? Or was it part of his death, sentenced to have his throat slit across a half-finished sawhorse? Or was it symbolic or cultural, like a knight slung over his horse, or merely coincidental, a sawhorse happening to be where the German fell?) We debated such questions when we encountered these meat puzzles: Who took the head of the partisan sentry? Why was the dead infant buried upside down in a grain bin? Based on smell and insect activity, this German meat puzzle on the sawhorse was two days past decent burial, and we hoped that if we ignored him we wouldn’t be ordered by our CO, the gap-toothed idiot Leftenent Bean, to deal with the ripening body.

We were safely past the body and burial detail when I suddenly stopped marching and sent word forward that I would deal with the stewing corpse. I had my reasons, of course. Someone had taken the dead German’s boots already, and he’d surely been picked clean of insignia and weaponry and anything else that might make a decent trophy to show to the nephews at Thanksgiving in Rockport (“This is the Hitler battle spoon I took from a murderous Hun I killed using my poor bare feet”), but for some reason this particular dead man still had his socks. And so crazed was I with discomfort that this dead man’s socks looked to me like salvation: two clean, tight-woven sheaths that appeared to cover his feet like bedsheets at a four-star hotel. After dozens of pairs of Allied replacement socks courtesy of my empathetic supply sergeant, I had thought I might try my luck with Axis footwear.

“That’s sick,” Richards said when I told him I was going back for the corpse’s socks.

“I’m sick!” I admitted. But before I could move for the dead man’s feet, that moron silver bar, Leftenent Bean, came astride and said that a mine-rigged body had been encountered by another platoon, and so our most recent orders were to eschew burial detail. I had to walk away from what appeared to be the warmest, driest, cleanest pair of socks in Europe, to march another two miles in these soggy, spiky beasts in full pupa stage. And that was it. I was done. I said to Richards, “I’m doing it tonight. SIW. I’m blowing off my foot tonight.”

Richards had been listening to me gripe for days, and he thought I was all talk, that I could no more shoot myself in the foot than I could levitate. “Don’t be stupid,” Richards said. “War’s over.”

That was what was so perfect, I told him. Who would suspect it now? Earlier in my war, a foot-shot might not have been enough to send me home, but now, with the thing winding down, I liked my odds. “I’m going to do it.”

Richards indulged me. “Fine. Do it. I hope you bleed to death in the stockade.”

“Death would be better than this pain.”

“Then forget your foot, shoot yourself in the head.”

We’d stopped just short of this village, and decamped in the rubble of an old barn on a vine-covered hillside. Richards and I set up OP on a small ledge that served as our cover. I sat there debating with Richards which part of my foot I should shoot, as easily as a man might talk about where to have lunch, and that’s when a scraping came from the road below us. Richards and I looked at one another silently. I grabbed my carbine, pushed up to the ledge, and rolled my sight along the road below us until I landed on the approaching figure of . . .

A girl? No. A woman. Young. Nineteen? Twenty-two? Twenty-three? I couldn’t say in the dusky light, only that she was lovely, and that she seemed to be bouncing alone on this narrow dirt road, brown hair swept up and pinned in back, face narrow at the chin, rising over flushed cheeks to a pair of eyes framed by bursts of black lash, like two lines of oil smoke. She was small, but everyone in the bruised shin of Italy was small. She didn’t appear to be starving. She wore a wrap over a dress and it pains me to not recall the color of that dress, but I believe it was a faded blue, with yellow sunflowers, though I can’t honestly say it was so, only that I remember it that way (and I find it suspicious that every woman in the Europe of my memory, every whore, grandmother, and waif I encountered, wears the same blue dress with yellow sunflowers).

“Halt,” Richards called. And I laughed. Here was a vision on a road beneath us and Richards comes up with Halt? Had I my wits beneath me instead of brutalized feet, I’d have steered him to the Bard’s more existential Who’s there? and we’d have done the whole of Hamlet for her.

“Don’t shoot, nice Americans,” called the girl from the road, in pristine English. Unsure where this “Halt” had come from, she addressed the trees on both sides, then our small ledge before her. “I am walking to see my mother.” She held up her hands and we rose on the hillside above her, rifles still trained. She lowered her hands and said that her name was Maria and that she was from the village just over the hill. Despite a slight accent, her English was better than most of the guys’ in our unit. She was smiling. Not until you see a smile like that do you understand how much you’ve missed it. All I could think about was how long it had been since I’d seen a smiling girl on a country road.

“Road’s closed. You’ll have to walk around,” Richards said, pointing with his rifle back the way she’d come.

“Yes, fine,” she said, and asked if the road to the west was open. Richards said it was. “Thank you,” she said, and started back up the road. “God bless America.”

“Wait,” I yelled. “I’ll walk you.” I took off my wool helmet liner and patted down my hair with spit.

“Don’t be an idiot,” Richards said.

I turned, tears in my eyes. “Goddamn it, Richards, I am walking this girl home!” Of course, Richards was right. I was being an idiot. Leaving my post was desertion, but at that moment I’d have spent the rest of my war in the stockade to walk six feet with that girl.

“Please, let me go,” I said. “I’ll give you anything.”

“Your Luger,” Richards said without hesitation.

I knew this was what Richards would ask for. He coveted that Luger as much as I coveted dry socks. He wanted it as a souvenir for his son. And how could I blame him? I had been thinking of the son I didn’t have when I bought the Luger at a little Italian market outside Pietrasanta. With no son back home, I’d figured to show it to my wayward girlfriends and my lousy nephews after too many whiskeys, when I’d pretend not to want to talk about my war, then would pull the rusted Luger from a bureau and tell the lazy shits how I wrestled it from a crazy German who killed six of my men and shot me in the foot. The black-market economy of German war trophies depended on such deception: retreating, starving Germans trading their broken weapons and their identifying insignia to starving Italians for bread, and the starving Italians in turn selling them as trophies to Americans like Richards and me, starved for proof of our heroism.

Sadly, Richards never got to give the Luger to his boy, because six days before we shipped home, me to listen to Cubs games on the radio, him to his wife and son, Richards died ingloriously of a blood infection he acquired in a field hospital, after surgery for a ruptured appendix. I never even got to see him after he went in for a fever and gut ache, our moron lieutenant simply informing me that he’d died (“Oh, Bender. Yeah. Look. Richards is dead”), the last and best of my friends to go in my war. And if this marks the end of Richards’s war, I offer this epilogue: A year later I found myself driving through Cedar Falls, Iowa, parking in front of a bungalow with an American flag on the brick porch, removing my cap, and ringing the doorbell. Richards’s wife was a short, boxy thing and I told her the best lie I could imagine, that his last words had been her name. And I handed his little boy the box with my Luger in it, said his daddy had taken it off a German soldier. And as I looked down on those ginger cowlicks, I ached for my own son, for the heir I would never have, for someone to redeem the life I was already planning to waste. And when Richards’s God-sweet boy asked whether his father had been “brave at the war,” I said, with all honesty, “Your dad was the bravest man I ever knew.”

And he was, because on the day I met the girl, Brave Richards said, “Just go. Keep your Luger. I’ll cover for you. Just tell me all about it afterward.”

If, in this confession of fear and discomfort during my war, I have portrayed myself as lacking in valor, I offer this evidence of my Galahad-like heart: I had no intention of laying a hand on that girl. And I needed Richards to know it, that I risked death and dishonor not to nick my willy, but simply to walk with a pretty girl on a road at night, to feel that sweet normalcy again.

“Richards,” I said. “I’m not gonna touch her.”

I think he could see I was telling the truth, because he looked pained. “Then Christ, let me go with her.”

I patted his shoulder, grabbed my rifle, and ran down the road to catch her. She was a fast walker, and when I came upon her, she had edged over to the side of the road. Up close, she was older than I’d thought, maybe twenty-five. She took me in warily. I put her at ease with my bilingual charm: “Scusi, bella. Fare una passeggiata, per favore?”

She smiled. “Yes. You may walk with me,” she said in English. She slowed and took my arm. “But only if you stop wiping your ass on my language.”

Ah. So it was love.

Maria’s mother had raised three sons and three daughters in this village. Her father had died early in the war and her brothers had been conscripted at sixteen, fifteen, and the last at twelve, dragged off to dig Italian trenches and, later, German fortifications. She prayed that at least one of her brothers was alive somewhere north of what was left of the Linea Gotica, but she didn’t hold out much hope. Maria gave me the quick history of her little village during the war, squeezed like a washcloth of its young men by Mussolini, then squeezed again by the partisans, again by the retreating Germans, until there were no males between the ages of eight and fifty-five, the town bombed, strafed, and picked clean of food and supplies. Maria had studied English at a convent school, and with the invasion found work as a nurse’s aide at an American field hospital. She was gone weeks at a time but always returned to the village to check on her mother and sisters.

“So when this is all finished,” I asked, “do you have a nice young man to marry?”

“There was a boy, but I doubt he’s alive. No, when this is over I will care for my mother. She is a widow whose three sons were taken from her. When she’s gone, maybe I’ll get one of you Americans to take me to New York City. I’ll live in the Empire State Building, eat ice cream every night in fancy restaurants, and grow fat.”

“I can take you to Wisconsin. You can get fat there.”

“Ah, Wisconsin,” she said, “the cheese and the dairy fields.” She waved her hand in front of her face as if Wisconsin lay just beyond the scrub trees alongside the road. “Cows, farms, and Madison, moon over the river, and the college of Badgers. It is cold in the winter but in the summer there are beautiful farm girls with pigtails and red cheeks.”

She could do that for any state you named, so many American boys in her hospital had taken time to reminisce about the place they came from, often before they died. “Idaho? The deep lakes and big mountains, endless trees and beautiful farm girls with pigtails and red cheeks.”

“No farm girl for me,” I said.

“You will find one after the war,” she said.

I said that after the war I wanted to write a book.

She cocked her head. “What kind of book?”

“A novel. About all of this. Maybe a funny novel.”

She became somber. Writing a book was an important thing to do, she said, not a joke.

“Oh, no,” I said, “I don’t mean to joke about it. I don’t mean that sort of funny.”

She asked what other kind of funny there was and I didn’t know what to say. We were within sight of her village, a cluster of gray shadows that sat like a cap on the dark hill in front of us.

“The sort of funny that makes you sad, too,” I said.

She looked at me curiously and just then, a bird or a bat flushed from the bushes ahead and we both started. I put my arm around Maria’s shoulder. And I can’t say how it happened, but suddenly we were off the road and I was on my back and she was lying on top of me in a grove of lemon trees, the unripe fruit above me like hanging stones. I kissed her lips and cheeks and neck and she quickly undid my pants and held me between her two hands, stroking me expertly with one soft hand and caressing me with the other, as if she had read some top secret army manual on this maneuver. And she was exceptional at it, far better than I’d ever managed to be, so that in no time I was making snuff ling noises and she pressed against me and I smelled lemons and dirt and her, and the world fell away as she shifted her body and aimed me perfectly away from her pretty dress, like a farmwife directing a stream of cow’s milk, toward the unripe lemons, all of this happening in less than a minute, without her having to so much as loosen the bow in her hair.

She said: “There you go.”

To this day, these three words remain the most lovely, sad, awful thing I have ever heard. There you go.

I started crying. “What is it?” she said.

“My feet hurt,” was all I could manage. But of course I wasn’t crying because of my feet. And while I was overcome with gratitude toward Maria, and with regret and nostalgia and relief over being alive this late in my war, I wasn’t crying for those reasons, either. I was crying because clearly I wasn’t the first brute that Maria had so efficiently and delicately brought to fruition using only her hands.

I was crying because, behind her speed and skill, her mastery of technique, there could only exist an awful history. This was a maneuver learned after encounters with other soldiers, when they pushed her to the ground and she wasn’t able to deflect them using only her hands.

There you go.

“Oh Maria . . .” I cried. “I’m sorry.” And I was clearly not the first brute to cry in her presence, either, because she knew just what was needed, unbuttoning the top of her blue dress and putting my head between her breasts, whispering, “Shh, Wisconsin, shh,” her skin so soft and butter-sweet, so wet with my tears that I cried harder and she said, “Shh, Wisconsin,” and I buried my face between those breasts as if her skin were my home, as if Wisconsin lay there, and to this day, it is the greatest place I have ever been, that narrow ribbed valley between those lovely hills. After a moment I stopped crying and managed to regain a bit of dignity, and five minutes later, after I had given her all of my money and cigarettes and pledged my undying love and sworn that I would return, I hobbled shamefully back to my sentry post, insisting to my disappointed, soon-to-be-dead best friend, Richards, that I did nothing more than walk her home.

God, this life is a cold, brittle thing. And yet it’s all there is. That night I settled into my mummy bag, no longer myself but a played-out husk, a shell.

Years passed and I found myself still a husk, still in that moment, still in the day my war ended, the day I realized, as all survivors must, that being alive isn’t the same thing as living.

There you go.

A year later, after I delivered the Luger to Richards’s son, I stopped at a little bar in Cedar Falls and had one of the six million drinks I’ve had since that day. The barmaid asked what I was doing in town and I told her, “Visiting my boy.” Then she asked about my son, that good imaginary boy whose biggest failing was that he didn’t exist. I told her that he was a fine kid, and that I was delivering a war souvenir to him. She was intrigued. What was it? she asked. What thing of significance had I brought home from the war for my boy? Socks, I answered.

But in the end, this is what I brought home from my war, this single sad story about how I lived while a better man died. How, beneath a scraggly lemon branch on a little dirt track outside the village of R—, I received a glorious twenty-second hand job from a girl who was desperately trying to avoid being raped by me.