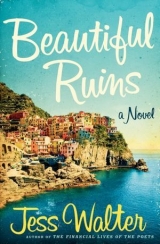

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

11

Dee of Troy

April 1962

Rome and Porto Vergogna, Italy

Richard Burton was the worst driver Pasquale had ever seen. He squinted in the direction of the road with one eye and held the wheel lightly between two fingers, elbow cocked. With the other hand he pinched a cigarette out the open window, a cigarette he seemed to have no interest in smoking. From the passenger seat, Pasquale stared at the burning stick in the man’s hand, wondering if he should reach over and grab it before the ash got to Richard Burton’s fingers. The Alfa’s tires chirped and squealed as he cornered his way out of the Roman Centro, some pedestrians yelling and waving their fists as he forced them back onto curbs. “Sorry,” he said, or “So sorry,” or “Bugger off.”

Pasquale hadn’t known that Richard Burton was Richard Burton until the woman from the Spanish Steps introduced them. “Pasquale Tursi. This is Richard Burton.” Moments before, she had led him away from the steps, still clutching the envelope from Michael Deane, down a couple of streets, up a staircase, through a restaurant and out the back door, until, finally, they’d come across this man in sunglasses, worsted slacks, a sports coat over a sweater and red scarf, leaning against the light blue Alfa in a narrow alley where there were no other cars. Richard Burton had removed his sunglasses and given a wry smile. He was about Pasquale’s height, with thick sideburns, tousled brown hair, and a cleft chin. He had the sharpest features Pasquale had ever seen, as if his face had been sculpted in separate pieces and then assembled on-site. He had faint pockmarks on his cheeks and a pair of unblinking, wide-set blue eyes. Most of all, he had the biggest head Pasquale had ever encountered. He’d never seen Richard Burton’s movies and knew his name only from the two women on the train the day before, but one look and there could be no doubt: this man was a cinema star.

At the woman’s urging, Pasquale explained the whole thing in halting English: Dee Moray coming to his village, waiting there for a mysterious man who didn’t come; the doctor’s visit and Pasquale’s trip to Rome, his mistakenly being sent off with the extras, waiting for Michael Deane and then the bracing meeting with the man, which began with him punching Deane in the chest, quickly led to Deane admitting that Dee was in fact pregnant and not dying, and ended with the envelope of cash that Deane offered as a payoff, an envelope Pasquale still held in his hand.

“God,” Richard Burton finally said, “what a heartless mercenary Deane is. I guess they’re getting serious about finishing this bloody picture, sending this shit to handle the budgets and the gossip and the rot. Well, he’s bollixed it all up. The poor girl. Listen, Pat,” and he put a hand on Pasquale’s arm, “take me to her, will you, old sport, so I can at least display a whiff of chivalry amid this fuck-all mess?”

“Oh.” Pasquale had finally caught up with things, and found himself a bit deflated that this man was his competition and not the sniveling Michael Deane. “Then . . . is your baby.”

Richard Burton had barely flinched. “It would appear to be the case, yes.” And twenty minutes later, here they were, in Richard Burton’s Alfa Romeo, barreling through the outskirts of Rome toward the autostrada and, eventually, Dee Moray.

“Brilliant to be out driving again.” Richard Burton’s hair was rustled by the wind and he spoke above the road noise. The sun glinted off his dark glasses. “I tell you, Pat, I envy the punch you landed on Deane. He’s a bloody first-flight ten-year-old cocksuck, that one. I’ll likely aim a bit higher when it’s my go.”

The burning cigarette reached Richard Burton’s fingers and he flicked it over the side of his door as if it were a bee that had stung him. “I trust you know I had nothing to do with sending that girl away. And I certainly didn’t know she was with child—not that I’m thrilled with that part. You know how these on-set things are.” He shrugged and looked out the side window. “But I like Dee. She’s . . .” He looked for the word and couldn’t find it. “I’ve missed her.” He brought his hand to his mouth and seemed surprised there was no cigarette in it. “Dee and I had a bit of history, and we became friends again when Liz’s husband was in town. Then Fox loaned me out to do some bloody stock-work on The Longest Day—likely to get rid of me awhile. I was in France when Dee got sick. I talked to her by phone and she said she’d gone to see Dr. Crane . . . that they’d diagnosed her with cancer. She was going to Switzerland for treatment, but we decided to meet once on the coast. I said I’d finish my work on The Longest Day and meet her in Portovenere, and I entrusted this blood-blister Deane to set it up. The blighter’s a master at insinuating himself. He said she’d taken a bad turn and gone on to Bern for treatment. That she would call me when she returned. What could I do?”

“Portovenere?” Pasquale asked. Then she had come to his village by mistake. Or because of Michael Deane’s deception.

“It’s this goddamn movie.” Richard Burton shook his head. “It’s Satan’s asshole, this bloody film. Flashbulbs everywhere . . . priests with cameras in their cassocks . . . leech fixers coming from the States to keep the girls and booze away . . . gossip columns jumping every time we have a bloody cocktail. I should’ve walked off months ago. It’s insanity. And do you know why it’s gone over this way? Do you? Because of her.”

“Dee Moray?”

“What?” Richard Burton looked over as if Pasquale hadn’t been listening. “Dee? No. No, because of Liz. It’s like having a bloody typhoon in your flat. And I didn’t come looking for this. Any of it. I was perfectly happy doing Camelot. Not that I could get a bloody handshake from Julie Andrews—though, trust me, I was not lacking for female companionship. No, I was done with the bloody moron cinema. Back to the stage for me, regain my promise, the art—all that rot. Then my agent calls, says Fox will buy me out of Camelot and pay me four times my price if I’ll roll around Liz Taylor in a robe. Four times! And I didn’t jump right away, either. Said I’d think about it. Show me the mortal man who has to think about that. But I did. And do you know what I was thinking?”

Pasquale could only shrug. It was like standing in a windstorm, listening to this man.

“I was thinking about Larry.” Richard Burton looked at Pasquale. “Olivier, lecturing me in that buggering-uncle voice of his.” Richard Burton stuck out his lower lip and assumed a nasal voice: “ ‘Dick, you will, of course, eventually have to make up your mind whether you wish to be a household word or an ac-TOR.’ ” He laughed. “Rotten old sotter. Last night of Camelot, I raised my glass in a toast to Larry and his bloody stage. Said I’d take the money, thank you, and within a week I’d drive that raven-haired Liz Taylor to her knees . . . or, rather, to mine.” He laughed again at the memory. “Olivier . . . Christ. In the end, really what does it matter, whether some Welsh coal miner’s son acts on the stage or the screen? Our names are writ in water anyway, as Keats said, so what’s it bloody matter? Old sots like Olivier and Gielgud can have their code and shove it up each other’s arses, bugger off, boys, and on with the parade, right?” Richard Burton glanced over his shoulder, his hair mixed and blended by the wind through the open convertible. “So I’m off to Rome, where I meet Liz, and let me tell you, Pat, I’ve never seen a woman like this. I mean, I’ve had a few in my day, but this one? Christ. Do you know what I said first time I met her?” He didn’t wait for Pasquale to answer. “I said, ‘Don’t know if anyone’s ever told you this . . . but you’re not a bad-looking girl.’ ”

He smiled. “And when those eyes settle on you? God, the world stops spinning . . . I knew she was married, and more to the point, she’s a bloody soul-eater, but I’m not made of steel either. Of course, any right blighter would choose being a great actor over being a household word if the stacks were the same, but that’s not really the choice, is it? Because they pile that fuck-all money on the scale, too, and God, man, they put on those tits and that waist . . . and Christ, those eyes—and the thing begins to tip, old sport, till the scale goes right over. No, no, we are definitely writ in water. Or cognac—if we’ve any luck at all.”

He winked and swerved and Pasquale put his hand on the dashboard. “Now, there’s an idea. Cognac? Keep an eye out, eh, sport?” He took a deep breath and returned to his story. “Of course, the newspapers get hold of Liz and me and her husband comes to town and I sulked a bit, spent four days pissed, and somewhere in there, sotted and sorry, I went back to Dee again for comfort. Every two weeks, I’d find myself knocking on her door.” He shook his head. “She’s clear, that one—smart. It’s a burden for an attractive woman to be so smart, to see through the curtain. She’d agree with Larry, I’m sure, that I’m wasting my talent making rubbish like this film. And I knew Dee was guns for me. I probably shouldn’t have pursued her, but . . . who are we but who we are, am I right?” He patted his chest with his left hand. “You wouldn’t happen to have another fag?”

Pasquale pulled out a cigarette and lit it for him. Richard Burton took a long drag and the smoke curled from his nose. “This Crane, the man who diagnosed Dee—Liz’s pill-pusher, man rattles when he walks. He and Deane cooked up this cancer rubbish to get Dee out of town.” He shook his head. “Goddamn it, what kind of hopeless bastard tells a girl with morning sickness that she’s dying of cancer? They’ll do anything, these people.”

He braked suddenly and the tires seemed to jump, like a scared animal, and the car careened off the road and screeched to a stop at a market on the outskirts of Rome. “You as thirsty as I am, sport?”

“I am hungry,” Pasquale said. “I have not eaten.”

“Right. Excellent. And you wouldn’t have any money, would you? I was so bollixed up when we left, I’m afraid I’m a bit underfunded.”

Pasquale opened the envelope and handed him a thousand-lira note. Richard Burton took the money and ran into the market.

He returned a few minutes later with two open bottles of red wine, gave one to Pasquale and settled the other between his legs. “What goddamn kind of place hasn’t got a bottle of cognac in it? Are we to write our names in grape piss then? Ah well, in a pinch, I suppose.” He took a long pull of the wine and noticed Pasquale watching him. “My father was a twelve-pint-a-day man. Being Welsh, I’ve got to keep it in control, so I only drink when I’m working.” He winked. “Which is why I’m always bloody working.”

Four hours later, the man responsible for impregnating Dee Moray had drunk all but a few tugs of both bottles of wine and had stopped for a third. Pasquale couldn’t believe how much wine the man could handle. Richard Burton parked the Alfa Romeo near the port in La Spezia, and Pasquale asked around in a harbor bar until a fisherman agreed to take them up the coast to Porto Vergogna for two thousand lire. The fisherman walked ten meters ahead of them down to his boat.

“I was born in a tiny village myself,” Richard Burton told Pasquale as they settled onto the wooden bench in the stern of the fisherman’s dank, ten-meter boat. It was a cold, dark evening and Richard Burton turned up the collar of his jacket against the sharp sea breeze. The boat’s captain stood three steps above them, the wheel in his hand as he rode a cross-chop out of the harbor, the froth rising up to the bow, rolling over, and then settling back, the salty air making Pasquale even hungrier.

The captain ignored them. His ears glowed a cold red in the brisk air.

Richard Burton leaned back and sighed. “The stain I’m from is called Pontrhydyfen. Sits in a little glen between two green mountains and is cut by a little river clear as vodka. Little Welsh mining town. And what do you think our river was called?”

Pasquale had no idea what he was talking about.

“Think about it. It’ll make perfect sense.”

Pasquale shrugged.

“Avon.” He waited for Pasquale to react. “Fancy bit of irony, no?”

Pasquale said that it was.

“Right . . . okay then, did someone mention vodka? Right, I did.” Richard Burton sighed wearily. Then he called up to the boat’s pilot, “Are we truly to have nothing to drink on board? Really? Captain!” The man ignored him. “He’s risking outright mutiny, don’t you think, Pat?” Then Burton leaned back again, resettled his collar against the cool air, and resumed telling Pasquale about the village where he grew up. “There were thirteen of us little Jenkinses, tit-suckers every last one, till the git after me. I was two when my poor ma finally gave out, sucked dry. We drained the poor woman like deflating a balloon. I got the last of it. My sister Cecilia raised me after that. The old blighter Jenkins was no help. Fifty already when I was born, drunk the minute the sun came up, I barely knew him—his name the only thing he ever gave me. Burton I got from an acting teacher, though I tell people it’s for Michael Burton. Anatomy of Melancholy? No? Right. Sorry.” He ran a hand over his own chest. “No, this is all a thing I invented, this . . . Burton. Dickie Jenkins is a petty little tit-pincher, but this Richard Burton chap . . . he bloody well soars.”

Pasquale nodded, the chop from the sea and Burton’s endless drunk talk conspiring to make him extremely sleepy.

“Jenkins boys all worked in the coalface, except me, and I only escaped by luck and Hitler. The RAF was my way out, and though I turned out too bloody blind to fly, it still got me into Oxford. Tell me, do you know what you say to a kid from my village when you see him at Oxford?”

Pasquale shrugged, worn down by the man’s constant chatter.

“You say, ‘Get back to cutting that privet!’ ” When Pasquale didn’t laugh, Richard Burton leaned in to explain. “The point being . . . not to blow up my own arse, but just so you know, I wasn’t always . . .” He looked for the word. “This. No, I understand what it is to live in the provinces. Oh, I’ve forgotten a lot, I’ll give you that, gotten soft. But I have not forgotten that.”

Pasquale had never encountered someone who talked as much as this Richard Burton. When he didn’t understand something in English, Pasquale had learned to change the subject, and he tried this now—in part just to hear his own voice again. “Do you play tennis, Richard Burton?”

“More a rugger by training . . . I like the rough and tumble. I’d have played club after Oxford, wing-forward, if not for the ease with which men of the dramatic arts bunk young women.” He stared off into space. “My brother Ifor, he was a top rugger. I’d have been his equal if I’d stayed at it, although I’d have been limited to the hockey-playing, big-breasted girls. From my vantage, the stage-jocks got a wider choice.” And then he said, to the captain again, “And you’re sure you don’t have just a nip on board, cap’n? No cognac?” When there was no answer, he fell back against the stern again. “Hope this arsehole goes down with his tub.”

Finally, they rounded the breakwater point and the icy wind broke as the boat slowed and they chugged into Porto Vergogna. They bumped against the wooden plug at the end of the pier, seawater lapping over the soggy, sagging boards. In the moonlight, Richard Burton squinted at the dozen or so stone-and-plaster houses, a couple of them lit by lanterns. “Is the rest of the village over the hill, then?”

Pasquale glanced to the top floor of his hotel, where Dee Moray’s window was dark. “No. Is only Porto Vergogna, this.”

Richard Burton shook his head. “Right. Of course it is. My God, it’s barely a crack in the cliffs. And no telephones?”

“No.” Pasquale was embarrassed. “Next year, maybe they come.”

“This Deane is fucking mad,” Richard Burton said, with what sounded to Pasquale almost like admiration. “I’m going to flog that little shit until he bleeds from his nipples. Bastard.” He stepped onto the dock as Pasquale paid the Spezia fisherman, who shoved off and chugged away without so much as a word. Pasquale started toward the shore.

Above them, the fishermen were drinking in the piazza, as if they were eagerly awaiting something. They moved around like bees disturbed from their hive. Now they pushed Tomasso the Communist forward and he began making his way down the steps to the shore. Even though Pasquale now understood that Dee Moray wasn’t dying after all, he felt certain that something terrible had happened to her.

“Gualfredo and Pelle came this afternoon in the long boat,” Tomasso said when he met them on the steps. “They took your American, Pasquale! I tried to stop them. So did your Aunt Valeria. She told them the girl would die if they took her. The American didn’t want to go, but that pig Gualfredo told her she was supposed to be in Portovenere, not here . . . that a man had come there for her. And she went with them.”

Since the exchange was in Italian, the news didn’t register with Richard Burton, who lowered the collar of his jacket again, smoothed himself, and glanced up at the small cluster of whitewashed houses. He smiled to Tomasso and said: “I don’t suppose you’re a bartender, old chap. I could use a shot before telling the poor girl she’s been bred.”

Pasquale translated what Tomasso had told him. “A man from another hotel has come and take away Dee Moray.”

“Taken her where?”

Pasquale pointed down the coast. “Portovenere. He say she supposed to be there and that my hotel can’t take care good of Americans.”

“That’s piracy! We can’t allow such a thing to stand, can we?”

They walked up to the piazza and the fishermen shared the rest of their grappa with Richard Burton while they talked about what to do. There was some talk of waiting until morning, but Pasquale and Richard Burton agreed that Dee Moray must know immediately that she wasn’t dying of cancer. They would go to Portovenere tonight. There was a buzz of excitement among the men on the cold, sea-lapped shore: Tomasso the Elder talked about slitting Gualfredo’s throat; Richard Burton asked in English if anyone knew how late the bars were open in Portovenere; Lugo the War Hero ran back to his house to get his carbine; Tomasso the Communist raised his hand in a kind of salute and volunteered to pilot the assault on Gualfredo’s hotel; and it was around this time Pasquale realized that he was the only sober man in Porto Vergogna.

He walked to the hotel and went inside to tell his mother and his Aunt Valeria that they were going down the coast, and to grab a bottle of port for Richard Burton. His aunt was watching from her window and describing what she saw to Pasquale’s mother, who was propped up in bed. Pasquale stuck his head in the doorway.

“I tried to stop them,” Valeria said. She looked grim. She handed Pasquale a note.

“I know,” Pasquale said as he read the note. It was from Dee Moray. “Pasquale, some men came to tell me that my friend was waiting for me in Portovenere and that there had been a mistake. I will make sure you get paid for your trouble. Thank you for everything. Yours—Dee.” Pasquale sighed. Yours.

“Be careful,” his mother said from her bed. “Gualfredo is a hard man.”

He put the note in his pocket. “I’ll be fine, Mamma.”

“Yes, you will be, Pasqo,” she said. “You are a good man.”

Pasquale wasn’t used to this outward affection, especially when his mother was in one of her dark moods. Maybe she was coming out of it. He walked into the room and bent over to kiss her. She had the stale smell she so often got when confined to her bed. But before he could kiss her, she reached out with a clawed hand and squeezed his arm as tightly as she could, her arm shaking.

Pasquale looked down at her shaking hand. “Mamma, I’m coming right back.”

He looked at his Aunt Valeria for help, but she wouldn’t look up. And his mother wouldn’t let go of his arm.

“Mamma. It’s okay.”

“I told Valeria that such a tall American girl would never stay here. I told her that she would leave.”

“Mamma. What are you talking about?”

She leaned back and slowly let go of his arm. “Go get that American girl and marry her, Pasquale. You have my blessing.”

He laughed and kissed her again. “I’ll go find her, but I love you, Mamma. Only you. There’s no one else for me.”

Outside, Pasquale found Richard Burton and the fishermen still drinking in the piazza. An embarrassed Lugo said they couldn’t borrow his carbine after all, because his wife was using it to stake some tomato plants in their cliff-side garden.

As they walked down toward the shore, Richard Burton nudged Pasquale and pointed to the Hotel Adequate View sign. “Yours?”

Pasquale nodded. “My father’s.”

Richard Burton yawned. “Bloody brilliant.” Then he happily took the bottle of port. “I tell you, Pat, this is one damn strange picture.”

The fishermen helped Tomasso the Communist dump his nets and gear and a sleeping cat into the piazza and they used the cart to wheel his outboard motor down to the water. Pasquale and Richard Burton climbed in. The fishermen stood watching from what was left of Pasquale’s beach. Tomasso’s first yank on the pull start knocked the bottle of port from Richard Burton’s hand, but luckily it landed in Pasquale’s lap without spilling much. He handed it back to the drunk Welshman. But the little motor refused to catch. They sat rocking in the waves, drifting slowly away, Richard Burton suppressing little belches and apologizing for each one. “Air’s a bit stagnant on this yacht,” he said.

“Bastard!” Tomasso yelled to the engine. He beat on it and pulled again. Nothing. The other fishermen yelled that it either wasn’t getting spark or wasn’t getting fuel, then those who’d said spark switched to fuel and fuel to spark.

Something came over Richard Burton then and he stood and, in a deep, resonant voice, addressed the three old fishermen yelling from the shore. “Fear not, Achaean brothers. I swear to you: tonight there will be the weeping of soft tears in Portovenere . . . tears for want of their dead sons . . . upon whom we now go to wage war, for the sake of fair Dee, that woman who so makes the blood run. I give you my word as a gentleman, as an Achaean: we shall return victorious, or not at all!” And while they didn’t understand a word of the speech, the fishermen could tell it was epic and they all cheered, even Lugo, who was pissing on the rocks. Then Richard Burton waved his bottle over his two crewmates, in a sort of benediction: Pasquale, huddled against the cold in the back of the boat, and Tomasso the Communist, who was adjusting the choke on the motor. “O you lost sons of Portovenere, prepare to meet the shock of doom borne down upon you by this fearless army of good men.” He put his hand on Pasquale’s head: “Achilles here and the smelly bloke pulling on the motor, I forget his name, fair men all, pitiless and powerful, and—”

Tomasso pulled, the motor caught, and Richard Burton nearly fell out, but Pasquale caught him and sat him down in the boat. Burton patted Pasquale on the arm and slurred, “ . . . more than kin, and less than kind.” They chugged away into the grain of the chop. Finally, the rescue party was away.

Onshore, the fishermen were drifting away to their beds. In the boat, Richard Burton sighed. He took a swig and looked once more at the little town disappearing behind the rock wall, as if it had never existed at all.

“Listen, Pat,” Richard Burton said, “I take back what I said before about being from a small village like yours.” He gestured with the bottle of port. “No, I’m sure it’s a fine place, but Christ, man, I’ve left bigger settlements in my rank trousers.”

They walked ashore and straight into Gualfredo’s recently remodeled albergo, the Hotel de la Mar in Portovenere. The desk clerk required even more of the money from Pasquale’s payoff from Michael Deane, but after they’d negotiated his outrageous price, the man gave them the bottle of cognac that Richard Burton wanted and the number of Dee Moray’s room. The actor had slept a little in the boat—Pasquale had no idea how—and now he swirled the cognac like mouthwash, swallowed, patted down his hair, and said, “Okay. Good as gold.” He and Pasquale climbed the stairs and walked down the hallway to the tall door of Dee’s room, Pasquale looking around at Gualfredo’s modern hotel and becoming embarrassed again that Dee Moray had ever stayed in his grubby little pensione. The smell of this place—clean and something he thought of as vaguely American—made him realize how badly the Adequate View must stink, the old women and rotting, damp sea-smell of the place.

Richard Burton walked in front of Pasquale, weaving on the carpet, righting the ship with each step. He patted down his hair, winked at Pasquale, and rapped lightly, with one knuckle, on the hotel room door. When there was no answer, he knocked louder.

“Who is it?” Dee Moray’s voice came from behind the door.

“Ah, it’s Richard, love,” he said. “Come to rescue you.”

A moment later the door flew open and Dee appeared in a robe. They crashed into each other’s arms and Pasquale had to look away or risk betraying his deep envy and embarrassment that he’d ever imagined that she could want to be with someone like him. He was a donkey watching two Thoroughbreds prance in a field.

After a few seconds, Dee Moray pushed Richard Burton away. In a voice both chiding and sweet, she asked him, “Where have you been?”

“I was looking for you,” Richard Burton said. “It’s been something of an odyssey. But, listen, there’s something I need to tell you. I’m afraid we’ve been the subjects of a frightful bit of deception here.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Come in. Sit down. I’ll explain the whole thing.” Richard Burton helped her back into her room and the door closed behind them.

Pasquale stood alone in the hallway then, staring at the door, unsure what to do, listening to the hushed conversation inside and trying to decide whether he should simply stand there, or knock on the door and remind them that he was out here, or just go back down to the boat with Tomasso. He yawned and leaned against the wall. He’d been at it for about twenty hours straight. By now, Richard Burton would have told her that she wasn’t dying, that she was in fact pregnant, and yet he heard none of the noises he’d have expected coming from behind the door at the revelation of this news—either a loud expression of anger, or the relief at the truth of her condition, or the shock that she was having a baby. A baby! she might yell. Or ask, A baby? Yet there was nothing behind the door but hushed voices.

Perhaps five minutes passed. Pasquale had just decided to leave when the door opened and Dee Moray came out alone, her robe pulled tight around her. She had been crying. She said nothing, just walked down the hall, her bare feet padding on the carpet. Pasquale pushed off the wall. She put her arms around his neck and hugged him tightly. He put his arms around her, the tapered notch of her waist; he felt the silk against her skin, and beneath her soft robe, her breasts against his chest. She smelled like roses and soap and Pasquale was suddenly horrified at the way he must smell after the day he’d had—trips on a bus and in a car and in two fishing boats—and only then did the unbelievable nature of this day fully register. Had he actually begun the day in Rome nearly cast as an extra in the movie Cleopatra? Then Dee Moray began to shudder like the old motor in Tomasso’s boat. He held her for a full minute and tried simply to let the minute be—the firmness of the body beneath the softness of that robe.

Finally, Dee Moray pulled away. She wiped at her eyes and looked into Pasquale’s face. “I don’t know what to say.”

Pasquale shrugged. “Is okay.”

“But I want to say something to you, Pasquale, I need to.” And then she laughed. “Thank you is not nearly enough.”

Pasquale looked down at the floor. Sometimes it was like a deep ache, the simple act of breathing in and out. “No,” he said. “Is enough.”

He pulled from his coat the envelope of money, much lightened since it had been handed to him on the Spanish Steps. “Michael Deane ask for me give you this.” She opened it and shook with revulsion at the bloom of currency. He didn’t mention that some of the money was meant for him; it made him feel complicit. “And these,” Pasquale said, and handed her the continuity photos of herself. On top was the picture of Dee and the other woman on the set of Cleopatra. She covered her mouth when she saw it. Pasquale said, “Michael Deane said I tell you—”

“Don’t ever tell me what that bastard said,” Dee Moray interrupted, not looking up from the photograph. “Please.”

Pasquale nodded.

She still hadn’t looked up from the continuity photos. She pointed to the other woman in the photo, the one with the dark hair, whose arm Dee Moray was holding as she laughed. “She’s actually quite nice,” she said. “It’s funny.” Dee sighed. She flipped through the other pictures and Pasquale realized now that in one of them she was standing grimly with two men, one of whom was Richard Burton.

Dee Moray looked back toward the open door of her hotel room. And then she wiped her teary eyes again. “I guess we’re going to stay here tonight,” she said. “Richard’s awfully tired. He has to go back to France for one more day of shooting. And then he’s going to come with me to Switzerland and . . . we’ll see this doctor together and . . . I guess . . . get it taken care of.”

“Yes,” Pasquale said, the words taken care of hanging in the air. “I am glad . . . you are not sick.”

“Thank you, Pasquale. Me, too.” Her eyes became wet. “I’m going to come back and see you sometime. Is that okay?”

“Yes,” he said, but he didn’t think for a second that he would ever see her again.

“We can hike back up to the bunker, see the paintings again.”

Pasquale just smiled. He concentrated, looking for the words. “The first night, you say something . . . that we don’t know when our story is start, yes?”