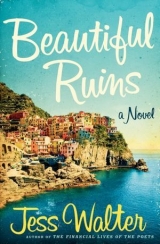

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

13

Dee Sees a Movie

April 1978

Seattle, Washington

She called him P.E. Steve, and he was at that very moment driving across town to pick her up for a date. Debra Moore-Bender had grown adept at deflecting the advances of her fellow teachers, but an attractive young widow was apparently too much for the sturdy Steve to abide, and for weeks he circled until he finally made his move—while they sat together at a desk outside a school dance, checking ASB cards beneath a banner that read: EVERLASTING LOVE. SPRING INTO ’78!

Debra gave him the usual excuse—she didn’t date other teachers—but Steve laughed this off. “What is that, like a lawyer-client thing? Because you know I teach phys ed, right? I’m not a real teacher, Debra.”

Her friend Mona had been urging Debra to date Steve ever since word of his divorce reached the teachers’ lounge—sweet Mona, whose own romantic life was a series of disasters but who somehow knew what was best for Debra. But what really convinced her was that P.E. Steve asked her to a movie. There was this movie she wanted to see—

And now, minutes before he was to pick her up, Debra stood in the bathroom staring into the mirror and running a brush through her feathered blond hair, which ruffled and settled like water in a boat’s wake (Miss Farrah, some of the students called her, a name she pretended to dislike). She turned to the side. This new hair color was a mistake. She’d spent a decade fighting the awful vanity of her youth and she’d really hoped, at thirty-eight, to be one of those women who were comfortable with middle age, but she just wasn’t there yet. Each gray hair still seemed like a weevil in a flower bed.

She glanced at the hairbrush. How many millions of strokes through her hair, how many face washings and sit-ups, how much work had she done—all to hear those words: beautiful, pretty, foxy. At one time, Debra accepted her looks without self-consciousness; she didn’t need affirmation—no “Miss Farrah” or leering P.E. Steve or even awkward, sweet Mona (“If I looked like you, Debra, I’d masturbate all the time”). But now? Dee set the hairbrush down, staring at it like some kind of talisman. She remembered singing into a brush like that when she was a kid; she still felt like a kid, like a nervous, needy fifteen-year-old getting ready for a date.

Maybe nerves were natural. Her last relationship had ended a year ago: her son Pat’s guitar teacher, Bald Marv (Pat nicknamed the men in her life). She’d liked Bald Marv, thought he stood a chance. He was older, in his late forties, had two older daughters from a failed marriage and was keen on “blending the families”—although he was decidedly less keen after he and Debra returned home one night to find Pat already blending, in bed with Marv’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Janet.

During Marv’s eruption she’d thought about defending Pat—Why do boys always get blamed in these situations? After all, Marv’s daughter was two years older than him. But this was Pat, and he proudly confessed his elaborate plans like a cornered Bond villain. It had been all his idea, his vodka, his condom. Debra wasn’t surprised that Bald Marv ended it. And while she hated breakups—the disingenuous abstractions, this is just not where I want to be right now, as if the other person had nothing to do with it—at least Bald Marv stated the case plainly: “I love you, Dee, but I do not have the energy to deal with this shit between you and Pat.”

You and Pat. Was it really that bad? Maybe. Three boyfriends ago, Coverall Carl, the contractor who worked on her house, had pushed her to get married, but wanted Debra to put Pat in a military school first. “Jesus, Carl,” she’d said, “he’s nine years old.”

And now, up to bat, P.E. Steve. At least his kids lived with their mother; maybe this time no civilians would get hurt.

She walked down the narrow hallway past Pat’s school picture—God, that smirk, in every picture, that same cleft-chin, wet-eyed, see-me smirk. The only thing that ever changed in his school pictures was his hair (floppy, permed, Zeppelin, spiked); the expression was always there—the dark charisma.

Pat’s bedroom door was closed. She knocked lightly, but he must have had headphones on, because he didn’t answer. Pat was fifteen now, old enough that she should be able to leave him home alone without some big speech every time she went out, but she couldn’t help herself.

Debra knocked again, then opened his bedroom door and saw Pat sitting cross-legged with his guitar across his lap, beneath a Pink Floyd poster of light going through a prism. He was leaning forward, his hand outstretched toward the top drawer of his nightstand, as if he’d just shoved something inside. She pressed into the room, pushing a pile of clothes out of the way. Pat took off the headphones. “Hey, Mom,” he said.

“What’d you put in the drawer?” she asked.

“Nothing,” Pat said too quickly.

“Pat. Are you going to make me look in there?”

“No one’s making you do anything.”

On the bottom shelf of his nightstand she saw the rat-eared, loose pages of Alvis’s book, at least the one chapter he’d written. She’d given it to Pat a year ago, after a big fight, during which he’d said he wished he had a father to go live with. “This was your father,” she said that night, hoping there was something in the yellowed pages to anchor the boy. Your father. She’d nearly come to believe it herself. Alvis had always insisted they tell Pat the truth once he got older, when he could understand, but as the years went on Debra had no idea how to do that.

She crossed her arms, like some picture from a parenting guide. “So are you going to open that drawer or am I?”

“Seriously, Mom . . . It’s nothing. Trust me.”

She moved toward the nightstand and he sighed, set his guitar down, and opened the drawer. He moved some things around and finally removed a small marijuana pipe. “I wasn’t smoking. I swear.” She felt the pipe, which was cool. No dope in it.

She searched the drawer; there was no marijuana. It was just a drawer full of junk—a couple of wristwatches, some guitar picks, his music composition books, pens and pencils. “I’m keeping the pipe,” she said.

“Sure.” He nodded as if that were obvious. “I shouldn’t have had it in there.” When he got in trouble, he always became strangely calm and reasonable. He’d break into this we’re-in-this-together mode that had always disarmed her; it was as if he were helping her deal with a particularly difficult child. He’d had the same quality at six. One time she’d stepped outside to get the mail, talked to her neighbor, and came back in to find Pat pouring a pan of water on the smoldering couch. “Wow,” he said, as if he’d just discovered the fire rather than set it. “Thank God I got to it early.”

Now he held up the headphones. Subject change: “You’d like this song.”

She looked down at the pipe in her hand. “Maybe I shouldn’t go out.”

“Come on, Mom. I’m sorry. Sometimes I fiddle around with things when I’m writing. But I haven’t gotten high in a month—I swear. Now go on your date.”

She stared at him, looking for some sign that he was lying, but his eye contact was as unwavering as ever.

“Maybe you’re just looking for an excuse to not go out,” Pat said.

That was like him, too, to turn it around on her, and to peg it on some real insight; it was true, she probably was looking for an excuse to not go out.

“Loosen up,” he said. “Go have fun. I’ll tell you what: you can borrow my P.E. clothes. Steve especially likes tight gray shorts.”

She smiled in spite of herself. “I think I’ll just go with what I’m wearing, thanks.”

“He’s gonna make you shower afterward, you know.”

“You think?”

“Yep: roll call, stretching, floor hockey, shower. That’s P.E. Steve’s dream date.”

“Is that so?”

“Yep. The guy’s fatuous.”

“Fatuous?” That was Pat, too, showing off his vocabulary while calling her date a moron.

“But don’t ask him if he’s fatuous, ’cause he’ll say, ‘Boy I hope so. I paid a lot for this vasectomy.’ ”

She laughed again in spite of herself—and wished, as always, that she hadn’t. How much trouble had Pat squirmed out of at school this way? Female teachers were especially helpless. He got As without books, talked other kids into doing his work, convinced principals to waive rules for him, ditched school and invented fabulist reasons for his absence. Debra would cringe during school conferences when the teacher asked about her diagnosis, or about Pat’s trip to South America, or about the death of his sister—Oh, and his poor father: murdered, disappeared in the Bermuda Triangle, dead of exposure on Everest. Every year, poor Alvis died all over again, of some new cause. Then, around his fourteenth birthday, Pat seemed to realize that he didn’t need to lie to get things, that it was more effective, and more fun, to simply look people in the eye and tell them exactly what he wanted.

She wondered sometimes if having a father around would have balanced her indulgence of him; she’d been overly charmed by his precociousness when he was little, and probably too lonely, especially in those dark years.

Pat set his guitar down and stood up. “Hey. I’m kidding about Steve. He seems nice.” He walked over. “Go. Have fun. Be happy.”

He really had grown in this last year. Anyone could see it. He’d gotten in less trouble at school, hadn’t snuck out of the house, had gotten better grades. Yet she was still discomfited by those eyes, not by their structure or color, but some quality in his stare—what people called a glimmer, a spark, a thrilling watch-this danger.

“Do you really want to make me happy?” Debra said. “Be here when I get home.”

“Deal,” he said, and stuck out his hand. “Okay if Benny comes over to practice?”

“Sure.” She shook his hand. Benny was the guitar player Pat had recruited for his band. This was the thing turning Pat around: his band, the Garys. She had to admit (after a couple of school events and a battle of the bands in Seattle Center), the Garys weren’t bad. In fact they were pretty good—not as punk as she’d feared, but kind of grubby and straightforward (when she’d likened them to Let It Bleed–era Stones, Pat rolled his eyes). And her son onstage was a revelation. He sang, preened, growled, joked; he exuded something up there that shouldn’t have surprised her but did: an effortless charm. Power. And ever since the band got together, Pat had been the picture of calm. What does it say about a kid that joining a rock band settles him down? But it was undeniable: he was focused and engaged. His motivation still worried her—he talked a lot about hitting it big, about becoming famous—and so she’d tried to explain the dangers of fame, but she couldn’t really be specific, could only make flat, bland speeches about the purity of art and the trappings of success. So she worried that her talk was all a waste of time, like warning a starving person about the dangers of obesity.

“I’ll be home in three hours,” Debra said now. It would be five or six hours, but this was a habit; cutting the time in half so he might get in only half the trouble. “Until then, don’t . . . um . . . don’t . . . uh . . .”

As she looked for the proper scale of warning, Pat’s face broke into a smile, eyes tipping before the corners of his mouth began their slow climb. “Don’t do anything?”

“Yes. Don’t do anything.”

He saluted, smiled, put his headphones back on, grabbed his guitar, and plopped back on the bed. “Hey,” he said when she turned away. “Don’t let Steve talk you into jumping jacks. He likes to watch the jiggly parts.”

She eased the door closed and had just started down the hallway when she looked down at the pipe in her hands. Now, why would he take a pipe out of its hiding place if he didn’t have pot for it? And when she’d asked what he’d been doing, Pat had to dig around in the drawer for the pipe. Wouldn’t it be on top if he’d just thrown it in there? She turned in the hallway, went back, and threw the door open. Pat was sitting back on the bed with his guitar, the nightstand dresser open again. Now, though, he had open on the bed the thing he’d actually been hiding from her: his songwriting book. He was bent over it with a pencil. He sat up quickly, red-faced and furious: “What the hell, Mom?”

She stalked over and grabbed the notebook from his bed, not really sure what she was looking for, her mind going to that place parents’ minds went: Worst-case-scenario-land. He’s writing songs about suicide! About dealing drugs! She flipped to a random page: song lyrics, a few notations about melody—Pat had only a rudimentary understanding of music—fragments of sweet, pained lyrics, like any fifteen-year-old might write, a love song, “Hot Tanya” (awkwardly rhymed with I want ya), some faux-meaningful tripe about the sun and moon and eternity’s womb.

He reached for the notebook. “Put that down!”

She flipped forward, looking for whatever had been so dangerous that he’d give her his pot pipe rather than admit he was writing a song.

“Fucking put it down, Mom!”

She found the last page with writing on it—the song he must have been trying to hide—and her shoulders slumped when she saw the heading: “The Smile of Heaven,” the title of Alvis’s book. She read the chorus: I used to believe/He’d come back for me/Why’s heaven smiling/When this shit ain’t funny—

Oh. Debra felt awful. “I– I’m sorry, Pat. I thought—”

He reached up and took the notebook back.

She so rarely saw beneath Pat’s smooth, sarcastic surface that she sometimes forgot a boy was there—a hurt boy who was still capable of missing his father even though he didn’t remember him. “Oh, Pat,” she said. “You’d rather I thought you were smoking pot . . . than writing a song?”

He rubbed his eyes. “It’s a bad song.”

“No, Pat. It’s really good.”

“It’s maudlin crap,” he said. “And I knew you’d make me talk about it.”

She sat on the bed. “So . . . let’s talk about it.”

“Ah, Jesus.” He looked past her, at a point on the floor. Then he blinked, laughed, and this seemed to snap him out of some trance. “It’s no big deal. It’s just a song.”

“Pat, I know it’s been hard on you—”

He winced. “I don’t think you understand just how much I don’t want to talk about this. Please. Can’t we talk about it later?”

When she didn’t budge, Pat pushed her gently with his foot. “Come on. I have more maudlin crap to write and you’re going to be late for your date. And when you’re tardy, P.E. Steve makes you run laps.”

P.E. Steve drove a Plymouth Duster with deep bucket seats. He had a gone-to-seed-superhero look, with blocky, side-parted hair and a square jaw, and an athletic body just starting to swell with middle age. Men have a half-life, she thought, like uranium.

“What should we see?” Steve asked her in the car.

She felt ridiculous even saying it: “The Exorcist II.” She shrugged. “I heard some kids in the library talking about it. It sounded good.”

“Fine with me. I figured you more for a foreign-film buff, something with subtitles that I’d have to pretend to understand.”

Debra laughed. “It has a good cast,” she said, “Linda Blair, Louise Fletcher, James Earl Jones.” She could barely even say the real name. “Richard Burton.”

“Richard Burton? Isn’t he dead?”

“Not yet,” she said.

“Okay,” P.E. Steve said, “but you might have to hold my hand. The first Exorcist scared the shit out of me.”

She looked out the window. “I didn’t see it.”

They ate dinner at a seafood place and she noted when he took one of her shrimp without asking. The conversation was easy and casual: Steve asking about Pat, Debra saying that he was doing better. Funny how every conversation about Pat assumed a baseline of trouble.

“You shouldn’t worry about him,” Steve said, as if reading her mind. “He’s a lousy floor-hockey player, but he’s a good kid. The talented ones like that? The more trouble they get in, the more successful they are as adults.”

“How do you know that?”

“ ’Cause I never got in trouble and now I’m a P.E. teacher.”

No, this wasn’t bad at all. They sat early in the theater with a shared box of Dots and a shared armrest, and shared backgrounds (She: widowed a decade earlier, mother dead, dad remarried, younger brother and two sisters; He: divorced, two kids, two brothers, parents in Arizona). Shared gossip, too: the one about some kids discovering a cache of the shop teacher’s raunchy porn above the lathe (He: I guess that’s why they call it wood shop) and Mrs. Wylie seducing the gear-head Dave Ames (She: But Dave Ames is just a boy; He: Yeah, not anymore).

Then the lights went down and they settled into their seats, P.E. Steve leaning over and whispering, “You seem different from how you are at school.”

“How am I at school?” she asked.

“Honestly? You’re kinda scary.”

She laughed. “Kinda scary?”

“No. I didn’t mean ‘kinda.’ Completely scary. Utterly intimidating.”

“I’m intimidating?”

“Yeah, I mean . . . look at you. You have seen yourself in a mirror, right?”

She was saved from the rest of this conversation by the coming attractions. Afterward, she leaned forward with anticipation, feeling the buzz she always felt when one of HIS films started. This one started with a mash of fire and locusts and devils, and when he finally came on, she felt both exhilaration and sadness: his face was grayer, ruddier, and his eyes, a version of those eyes she saw every day at home, but now like burned-out bulbs, the spark almost gone.

The movie swung from stupid to silly to incomprehensible, and she wondered if it would make more sense to someone who’d seen the first Exorcist. (Pat had snuck into a theater to see it and pronounced it “hilarious.”) The plot employed some kind of hypnosis machine made of Frankenstein wires and suction cups, which appeared to allow two or three people to have the same dream. When he wasn’t on-screen, she tried to concentrate on the other actors, to catch bits of business, interesting decisions. Sometimes, when she watched his films, she’d think about how she would’ve played a particular scene across from him—as she instructed her students: to notice the choices the actors made. Louise Fletcher was in this movie, and Debra marveled at her easy proficiency. Now there was an interesting career, Louise Fletcher’s. Dee could have had that kind of career—maybe.

“We can leave if you want,” P.E. Steve whispered.

“What? No. Why?”

“You keep scoffing.”

“Do I? I’m sorry.”

The rest of the movie she sat quietly, with her hands in her lap, watching as he struggled through ridiculous scenes, trying to find something to do with this drek. A few times, she did see bits of his old power crack through, the slight trill in that smooth voice overcoming his boozy diction.

They were quiet walking to the car. (Steve: That was . . . interesting. Debra: Mmm.) On the way home she stared out her window, lost in thought. She replayed her conversation with Pat earlier, wondering if she hadn’t missed some important opening. What if she’d just come out and told him: Oh, by the way, I’m on my way to see a movie starring your real father—but could she imagine a scenario in which that information helped Pat? What was he going to do? Go play catch with Richard Burton?

“I hope you didn’t pick that movie on purpose,” said P.E. Steve.

“What?” She squirmed in the seat. “I’m sorry?”

“Well, just that it’s hard to ask someone out for a second date after a movie like that. Like asking someone to go on another cruise after the Titanic.”

She laughed, but it was hollow. She pretended, to herself, that she went to all of his movies and kept an eye on his career because of Pat—in case it made sense to tell him one day. But she could never tell him; she knew that.

So, if it wasn’t for Pat, why did she still go to the movies—and sit there like a spy watching him destroy himself, daydreaming herself into supporting roles, never the Liz parts, always Louise Fletcher? Although it was never her, of course, not Debra Moore the high school drama and Italian teacher, but the woman she’d tried to create all those years ago, Dee Moray—as if she’d cleaved herself in two, Debra coming back to Seattle, Dee waking up in that tiny hotel on the Italian coast and getting sweet, shy Pasquale to take her to Switzerland, where she would do what they’d wanted, trade a baby for a career, and it was that career she still fantasized about—after twenty-six movies and countless plays, the veteran finally gets a supporting actress nomination—

In the bucket seat of P.E. Steve’s Duster, Debra sighed. God, she was pathetic—a schoolgirl forever singing into hairbrushes.

“You okay?” P.E. Steve said. “It’s like you’re fifty miles away.”

“I’m sorry.” She looked over and squeezed his arm. “I had this weird conversation with Pat before I left. I guess I’m still upset about it.”

“You want to talk about it?”

She almost laughed at the idea—confessing the whole thing to Pat’s P.E. teacher. “Thanks,” she said. “But no.” Steve went back to driving and Debra wondered if such a man’s matter-of-fact ease could still have some effect on the fifteen-year-old Pat, or if it was too late for all of that.

They pulled up to her house and Steve turned off the car. She wouldn’t mind going out with him again, but she hated this part of dates—the turn in the driver’s seat, the awkward seeking out of eyes, the fitful kiss and request to see her again.

She glanced over at the house to make sure Pat wasn’t watching—no way she could stand him teasing her about a good-bye kiss—and that’s when she saw something was missing. She got out of the car as if in a trance, started walking toward the house.

“So that’s it?”

She glanced over to see that P.E. Steve had gotten out of the car.

“What?” she said.

“Look,” he said, “this might not be my place, but I’m just gonna say it. I like you.” He leaned on the car, his arm propped on his open door. “You asked me what you were like at school . . . and, honestly, you’re like you’ve been the last hour. I said you were intimidating because of the way you look, and you are. But sometimes it’s like you’re not even in the room with other people. Like no one else even exists.”

“Steve—”

But he wasn’t done. “I know I’m not your type. That’s fine. But I think you might be a happier person if you let people in sometimes.”

She opened her mouth to tell him why she’d gotten out of the car, but you might be a happier person pissed her off. She might be a happier person? She might be a– Jesus. She stood there silently—broken, seething.

“Well, good night.” Steve got in his Duster, closed the door, and drove away. She watched his car turn at the end of the street, taillights blinking once.

Then she looked back at her house, and the empty driveway, where her car should have been parked.

Inside, she opened the drawer where she kept the spare car keys (gone, of course), peeked in Pat’s bedroom (empty, of course), looked for a note (none, of course), poured herself a glass of wine, and sat by the window, waiting for him to come home on his own. It was two forty-five in the morning when the phone finally rang. It was the police. Was she . . . Was her son . . . Did she own . . . tan Audi . . . license plate . . . She answered: Yes, yes, yes, until she stopped hearing the questions, just kept saying Yes. Then she hung up and called Mona, who came over and picked her up, drove her quietly to the police station.

They stopped and Mona put her hand on Debra’s. Good Mona—ten years younger and square-shouldered, bob-haired, with sharp green eyes. She’d tried to kiss Debra once after too many glasses of wine. You can always spot the real thing, that affection; why does it always come from the wrong person? “Debra,” Mona said, “I know you love that little fucker, but you can’t put up with his shit anymore. You hear me? Let him go to jail this time.”

“He was doing better,” Debra said weakly. “He wrote this song—” But she didn’t finish. She thanked Mona, got out of the car, and went into the police station.

A thick, uniformed officer in teardrop glasses came out with a clipboard. He said not to worry, her son was fine, but her car was totaled—it had gone over an abutment in Fremont, “a spectacular crash, amazing no one was hurt.”

“No one?”

“There was a girl in the car with him. She’s fine, too. Scared, but fine. Her parents already came down.”

Of course there was a girl. “Can I see him?”

In a minute, the officer said. But first she needed to know that her son had been intoxicated, that they’d found a vodka bottle and cocaine residue on a hand mirror in the car, that he was being cited for negligent driving, driving without a license, failure to use proper care and caution, driving under the influence, minor in possession. (Cocaine? She wasn’t sure she’d heard right but she nodded at each charge, what else could she do?) Given the severity of the charges, this matter would be turned over to the juvenile prosecutor, who would make a determination—

Wait. Cocaine? Where would he get cocaine? And what did P.E. Steve mean that she didn’t let people in? She’d love to let someone in. No, you know what she’d do? Let herself out! And Mona? Don’t put up with his shit? Jesus, did they think she chose to be this way? Did they think she had a choice in the way Pat behaved? God, that would be something, just stop putting up with Pat’s shit, go back in time and live some other life—

(Dee Moray reclines on a beach chair on the Riviera with her quiet, handsome Italian companion, Pasquale, reading the trades until Pasquale kisses her and goes off to play tennis on this court jutting out of the cliffs—)

“Any questions?”

“Hmm. I’m sorry?”

“Any questions about what I’ve just told you?”

“No.” She followed the fat cop down a hallway.

“This might not be the best time,” he said, and glanced back at her over his shoulder as they walked. “But I noticed that you’re not wearing a wedding ring. I wondered if maybe sometime you might want to have dinner . . . the legal system can be really confusing and it can help to have someone who—”

(The hotel concierge brings a phone to the beach. Dee Moray removes her sun hat and puts the phone to her ear. It’s Dick! Hello, love, he says, I trust you’re as beautiful as ever—)

The cop turned and handed her a card with his phone number on it. “I understand this is a tough time, but in case you feel like going out sometime.”

She stared at the card.

(Dee Moray sighs: I saw The Exorcist, Dick. Oh Jesus, he says, that shite? You know how to hurt a fellow. No, she tells him gently, it’s not exactly the Bard. Dick laughs. Listen, darling, I’ve got this play I thought we might do together—)

The cop reached for the door. Debra took a deep, ragged breath and followed him inside.

Pat was sitting on a folding chair in an empty room, head in his hands, fingers lost in those currents of wavy brown hair. He pushed his hair aside and looked up at her; those eyes. No one understood how much they were in this together, Pat and her. We’re lost in this thing, Dee thought. There was a small abrasion on his forehead, almost like a carpet burn. Otherwise, he looked fine. Irresistible—his father’s son.

He leaned back and crossed his arms. “Hey,” he said, mouth rising up in that sly what-are-you-doing-here smile. “So how was your date?”