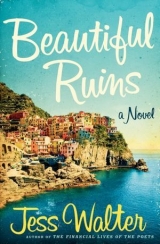

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

8

The Grand Hotel

April 1962

Rome, Italy

Pasquale slept uneasily in an expensive little albergo near the terminal station. He wondered how guests in these Rome hotels slept with all the noise. He rose early, slipped into his pants, shirt, tie, and jacket, had a caffè, and then took a cab to the Grand Hotel, where the American film people were staying. He smoked a cigarette on the Spanish Steps as he prepared himself. Vendors were setting up cut-flower stands and tourists were already flitting about, clutching folded maps, cameras around their necks. Pasquale looked down at the name on the paper that Orenzio had given him and said the name quietly so he wouldn’t mess it up.

I am here to see . . . Michael Deane. Michael Deane. Michael Deane.

Pasquale had never been inside the Grand Hotel. The mahogany door opened onto the most ornate lobby he’d ever seen: marble floors, floral frescoes on the ceilings, crystal chandeliers, stained-glass skylights depicting saints and birds and glum lions. It was hard to take it all in and he had to force himself not to gape like a tourist, to appear serious and focused. He had important business with the bastard Michael Deane. People were milling about in the lobby, groups of tourists and Italian businessmen in black suits and eyeglasses. Pasquale didn’t see any film stars, but then he wouldn’t have known what they looked like, either. He rested for a moment against a white sculpted lion, but its face was so much like a human’s that it made Pasquale uncomfortable and he moved on to the front desk.

Pasquale removed his hat and handed the desk clerk the piece of paper with Michael Deane’s name on it. He opened his mouth to say his line, but the clerk looked at the paper and pointed to an ornate doorway at the end of the lobby. “End of the hall.” A long line of people stretched and winded out the doorway where the clerk pointed.

“I have business with this man, Deane. He’s in there?” he asked the clerk.

The man just pointed and looked away. “End of the hall.”

Pasquale made his way to the back of the line at the end of the hall. He wondered if these people all had business with Michael Deane. Maybe the man had sick actresses squirreled all over Italy. The woman in line in front of Pasquale was attractive—straight brown hair and long legs, maybe his age, twenty-two or twenty-three, wearing a tight dress and nervously fingering an unlit cigarette.

“Do you have a light?” she asked.

Pasquale struck a match and held it for her. She cupped his hand and breathed in.

“I’m so nervous. If I don’t smoke right now I’m going to have to eat a whole cake. Then I’ll be as fat as my sister and they’ll have no use for me.”

He looked past her, along the line of people, into an ornate ballroom, big gold pillars in the corners.

“What is this line?” he asked.

“This is the only way,” she answered. “You can try to get in at the studio or wherever they’re filming that day, but I think the lines all go to the same place. No, the best way is to do what you did, just come here.”

Pasquale said, “I am trying to find this man.” He showed her the piece of paper with Deane’s name on it.

She glanced at the paper, and then showed him her own piece of paper, which had the name of a different man on it. “It doesn’t matter,” she said. “All of the lines lead to the same place eventually.”

More people fell in line behind Pasquale. The line led to a small table, where a man and a woman were seated with several stapled sheets of paper in front of them. Perhaps the man was Michael Deane. The man and the woman asked each person in line a question or two and then either sent them back the way they’d come, or to stand in the corner or out another door that seemed to lead outside.

When it was the beautiful girl’s turn, they took her paper, asked her age and where she was from, and whether she spoke any English. She said nineteen, Terni, and yes she spoke “English molto good.” They asked her to say something.

“Baby, baby,” she said in something like English. “I love you, baby. You are my baby.” She was sent to stand in the corner. Pasquale noticed that all the attractive young girls were sent to this same corner. The other people were sent out the door. When it was his turn, he showed the piece of paper with Michael Deane’s name to the man at the small table, who handed it back.

“Are you Michael Deane?” Pasquale asked.

“Identification?” the man said in Italian.

Pasquale handed over his ID card. “I’m looking for this man, Michael Deane.”

The man glanced up, then flipped through the pages, and finally wrote Pasquale’s name on one of the last pages, which was filled with dozens of names like his, written in the man’s handwriting.

“Any experience?” the man asked.

“What?”

“Acting experience.”

“No, I am not an actor. I am trying to find Michael Deane.”

“Speak English?”

“Yes,” Pasquale said in English.

“Say something.”

“Hello,” he said in English. “How are you?”

The man looked intrigued. “Say something funny,” he said.

Pasquale stood a moment and then said, in English, “I ask if she love him and she say yes. I ask if . . . he is in love, too. She say yes, the man love himself.”

The man didn’t smile but he said, “Okay,” and handed Pasquale’s ID card back, along with a card that had a number on it. The number was 5410. He pointed to the exit that most everyone else had been taking, except the beautiful girls. “Bus number four.”

“No, I am try to find—”

But the man had moved on to the next person in line.

Pasquale followed the snaking line out to a row of buses. He got on the fourth bus, which was nearly full of men between the ages of twenty and forty. After a few more minutes, he saw the lovely women loaded onto a smaller bus. When some more men had gotten on his bus, its door squeaked closed and the engine rumbled to life and the bus started off. They were driven through the city to an area in the centro that Pasquale didn’t recognize, where the bus stopped. Slowly, the men climbed off the bus. Pasquale could think of nothing to do but follow them.

They walked down an alley and through a gate marked CENTURIONS. And sure enough, inside the high fence, costumed Roman centurions were standing everywhere, smoking, eating panini, reading newspapers, talking to one another. There were hundreds of these men wearing armor and holding spears. There were no cameras or film crews anywhere, just men in centurion costumes wearing wristwatches and fedoras.

He felt rather foolish doing it, but Pasquale followed the line of men not yet in costume. The line led to a small building, where the men were being measured and fitted. “Is there someone of authority around?” he asked the man in front of him.

“No. That’s what’s so great.” The man opened his jacket and showed Pasquale that he had five of the numbered cards that had been given away at the hotel. “I just keep going through the line. The idiots pay me every time. I don’t ever even get a costume. It’s almost too easy.” The man winked.

“But I’m not supposed to be here,” Pasquale said.

The man laughed. “Don’t worry. They won’t catch you. They won’t film today anyway. It’ll rain or someone won’t like the light or after an hour someone will come out and say, ‘Mrs. Taylor is ill again,’ and they’ll send us home. They film only one of every five days, at most. During the rains, I knew a man who got paid six times each day just to show up. He’d go to all of the extra locations and get paid at each one. They finally caught on and kicked him out. Do you know what he did? He stole a camera and sold it to an Italian film company and do you know what they did? Sold it back to the Americans at twice the price. Ha!”

As they moved forward, a man in a tweed suit was walking toward them, down the line. He was with a woman holding a clipboard. The man was speaking English in quick, furious bursts, telling the woman with the clipboard various things to write down. She nodded and did as he said. Sometimes he sent the people out of line and they left happily. When he got to Pasquale, the man stopped and leaned in extremely close. Pasquale leaned back.

“How old is he?”

Pasquale answered in English before the woman could translate. “I am twenty-two years.”

Now the man took Pasquale by the chin and turned his face so that he could look directly in his eyes. “Where’d you get the blue eyes, pal?”

“My mother, she has blue eyes. She is Ligurian. There are many blue eyes.”

The man said to the interpreter, “Slave?” and then to Pasquale, “You want to be a slave? I can get you a little more pay. Maybe even more days.” Before he could answer, the man said to the woman, “Send him over to be a slave.”

“No,” Pasquale said. “Wait.” He dug out the paper again and spoke to the man in the tweed suit in English. “I am only try to find Michael Deane. In my hotel is an American. Dee Moray.”

The man turned his body fully to Pasquale. “What did you say?”

“I am try to find—”

“Did you say Dee Moray?”

“Yes. She is in my hotel. This is why I come to find this Michael Deane. She has wait for him and he doesn’t come. She is very sick.”

The man looked down at the piece of paper and then made eye contact with the woman. “Jesus, we heard Dee went to Switzerland for treatment.”

“No. She come to my hotel.”

“Well, goddamn it, man, what are you doing with the extras?”

A car took him back to the Grand Hotel and he sat in the lobby, watching the light glint off a crystal chandelier. There was a staircase behind him, and every few minutes someone would saunter down, as if their appearance would lead to applause. The lifts dinged every few minutes as well, but still no one came for him. Pasquale smoked and waited. He thought of going to the room at the end of the hall and asking someone where he could find Michael Deane but he was afraid they’d just put him on a bus again. Twenty minutes passed. Then another twenty. Finally, an attractive young woman approached. There seemed to be no shortage of these.

“Mr. Tursi?”

“Yes.”

“Mr. Deane is so sorry to have kept you waiting. Please, come with me.” Pasquale followed her to the lift and the operator took them to the fourth floor. The hallways were well-lit and wide and Pasquale was embarrassed to think of Dee Moray leaving this beautiful hotel for his little pensione, with its narrow staircase, where there hadn’t been room for the full height of the ceiling and so the builder had simply used the native boulders, blending the wall into the rock ceiling, as if a cave were slowly eating his hotel.

He followed the woman into a suite, the doors connecting several rooms flung open. There appeared to be a great deal of work going on in this suite—people talking on telephones and typing, as if a small business had taken root here. There was a long table of food and lovely Italian girls circulating with coffee. One of them, he saw, was the girl he’d seen in line. But she wouldn’t meet his eyes.

Pasquale was rushed through the suite and onto a terrace overlooking the church of Trinità dei Monti. He thought again of Dee Moray, of her saying what a beautiful view she had from her room, and he was embarrassed.

“Please, sit down. Michael will be right with you.”

Pasquale sat in a wrought-iron chair on the terrace, the sound of all that typing and talking going on behind him. He smoked. He waited another forty minutes. Then the attractive woman returned. Or was it a different one? “It will be a few more minutes. Would you like some water while you wait?”

“Yes, thank you,” Pasquale said.

But the water never arrived. It was after one now. He’d been trying to find Michael Deane for more than three hours. He was thirsty and hungry.

Another twenty minutes passed and the woman returned. “Michael is waiting for you down in the lobby.”

Pasquale was shaking—with anger or hunger, he couldn’t tell—as he stood and followed her through the suite again and out into the hallway, back down in the lift and to the lobby. And there, sitting on the very couch where he’d been an hour earlier, was a man far younger than Pasquale had imagined—as young as him—a fair, pale American with thin, reddish brown hair. He was chewing his right thumbnail. He was handsome enough, in that washed-out American way, but he lacked some quality that Pasquale would have assigned to the man that Dee Moray was waiting for. Maybe, he thought, there is no man good enough for her.

The man stood. “Mr. Tursi,” he said in English. “I’m Michael Deane. I understand you’ve come to talk about Dee.”

What Pasquale did next surprised even him. He hadn’t done anything of the kind since a night years ago in La Spezia, when he was seventeen and one of Orenzio’s brothers impugned his manhood, but at that very moment he stepped in and punched Michael Deane—in the chest, of all places. He’d never hit anyone in the chest, had never even seen anyone hit in the chest. It hurt his whole arm, and made a dull thud, and dropped Deane right back onto the couch, folded over like a garment bag.

Pasquale stood above the folded man, shaking and thinking, Stand up. Stand up and fight; let me hit you again. But slowly Pasquale’s anger faded. He looked around. No one had seen the punch. It must’ve looked as if Michael Deane had simply taken his seat again. Pasquale stepped back a little.

After he caught his breath, Deane unrolled, looked up with a grimace, and said, “Ow! Shit.” Then he coughed. “I suppose you think I deserved that.”

“Why you leave her alone like this! She is scared. And sick.”

“I know. I know. Look, I’m sorry about how things turned out.” Deane coughed again and rubbed his chest. He looked around warily. “Can we talk about this outside?”

Pasquale shrugged and they walked toward the door.

“No more hitting, right?”

Pasquale agreed and they left the hotel and walked outside to the Spanish Steps. The piazza was full, merchants yelling out prices for flowers. Pasquale waved them off as they walked deeper into the piazza.

Michael Deane continued to rub his chest. “I think you broke something.”

“Dispiace,” Pasquale muttered, even though he wasn’t sorry.

“How is Dee?”

“She is sick. I bring a doctor from La Spezia.”

“And your doctor . . . examined her?”

“Yes.”

“I see.” Michael Deane nodded grimly and started in on his thumbnail again. “Then I don’t suppose I need to guess what the doctor told you.”

“He ask for her doctor. To talk.”

“He wants to talk to Dr. Crane?”

“Yes.” Pasquale tried to remember the exact conversation, but he knew the translation would be impossible.

“Look, you should know that none of this was Dr. Crane’s idea. It was mine.” Michael Deane pulled back, as if Pasquale might hit him again. “All Dr. Crane did was explain to her that her symptoms were consistent with cancer. Which they are.”

Pasquale wasn’t sure he understood. “Are you come to get her now?” he asked.

Michael Deane didn’t answer right away, but looked around the piazza. “Do you know what I like about this place, Mr. Tursi?”

Pasquale looked at the Spanish Steps, at the wedding-cake ascension of stairs leading up to the church of Trinità dei Monti. On the steps nearest him, a young woman was leaning forward on her knees, reading a book while her friend drew on a sketch pad. The steps were covered with people like this, reading, taking photographs, and in intimate conversations.

“I like the self-interest of the Italian people. I like that they aren’t afraid to ask for exactly what they want. Americans are not like that. We talk around our intentions. Do you know what I mean?”

Pasquale didn’t. But he also didn’t want to admit it and so he just nodded.

“You and I should explain our positions. I’m obviously in a difficult position and you appear to be someone who can help.”

Pasquale was having trouble concentrating on these meaningless words. He couldn’t imagine what Dee Moray saw in this man.

They had reached the Fountain of the Old Boat in the center of the piazza—the Fontana della Barcaccia. Michael Deane leaned against it. “Do you know about this fountain, the sinking boat?”

Pasquale looked at the sculpted boat in the center of the fountain, water roiling up through the center of it. “No.”

“It’s unlike any other sculpture in the city. All of these earnest, serious pieces and this one, it’s comic—ridiculous. To my thinking, that makes it the truest piece of art in the city. Do you know what I mean, Mr. Tursi?”

Pasquale didn’t know what to say.

“A long time ago, during a flood, the river lifted a boat and dumped it here, where the fountain sits today. The artist was trying to capture the random nature of disaster.

“His point was this: sometimes there is no explanation for the things that happen. Sometimes a boat simply appears on a street. And as odd as it may seem, one has no choice but to deal with the fact that there’s suddenly a boat on the street. Well . . . such is the position I find myself in here in Rome, on this movie. Except it’s not just one boat. There are fucking boats on every fucking street.”

Again, Pasquale had no idea what the man meant.

“You may think what I’ve done to Dee is cruel. I won’t argue that, from a certain vantage, it was. But I just deal with whatever disasters arise, one at a time.” With that, Michael Deane produced an envelope from his suit coat. He pressed it into Pasquale’s hand. “Half is for her. And half is for you, for what you’ve done and for what I hope you can do for me now.” He put a hand on Pasquale’s arm. “Even though you’ve assaulted me, I’m going to consider you a friend, Mr. Tursi, and I will treat you as a friend. But if I find out that you have given her less than half or that you have talked to anyone about this, I will no longer be your friend. And you don’t want that.”

Pasquale pulled his arm away. Was this awful man accusing him of being dishonest? He remembered Dee’s word and he said, “Please! I am frank!”

“Yes, good,” Michael Deane said, holding up his hands as if he were afraid Pasquale would hit him again. Then his eyes narrowed and he stepped in close. “You want to be frank? I can be frank. I was sent here to save this dying movie. That’s my only job. My job has no moral component. It is not good and it is not bad. It is merely my job to get the boats off the streets.”

He looked away. “Obviously your doctor is right. We misled Dee to get her out of here. I’m not proud of myself for that. Please tell her, Dr. Crane shouldn’t have chosen stomach cancer. He didn’t mean to scare her. You know doctors—almost too analytical. He chose it because the symptoms could match up with those of early pregnancy. But it was only supposed to be for a day or two. That’s why she was supposed to go to Switzerland. There’s a doctor there who specializes in unwanted pregnancies. He’s safe. Discreet.”

Pasquale was a few steps behind. So it was true. She was pregnant.

Michael Deane reacted to Pasquale’s look. “Look, please tell her how sorry I am.” Then he patted the envelope in Pasquale’s hand. “Tell her . . . it’s the way things sometimes are. And I am truly sorry. But she needs to go to Switzerland as Dr. Crane advised her to do. The doctor there will take care of everything. It’s all paid for.”

Pasquale stared at the envelope in his hands.

“Oh, and I have something else for her.” He reached in the same jacket pocket and removed three small, square photographs. They appeared to have been taken on the set of the movie—he could see a camera crew in the background of one—and while the pictures were small, Pasquale could see clearly, in all three of them, Dee Moray. She wore a kind of long, flowing dress and was standing with another woman, both of them flanking a third woman, a beautiful, dark-haired woman who was in the foreground of the pictures. In the best photo, Dee and this dark-haired woman were leaning back, caught by the photographer in a genuine moment, dissolving in laughter. “These are continuity photos,” Michael Deane said. “We use these pictures to make sure we get the setup for the next shot right. Costumes, hair . . . make sure no one puts on a wristwatch. I thought Dee might want to have these.”

Pasquale looked hard into the top photo. Dee Moray had her hand on the other woman’s arm, and they were laughing so hard that Pasquale would have given anything right then to know what was so funny. Maybe it was the same joke she’d shared with him, about this man who loved himself so much.

Deane was looking down at the top photo, too. “She has an interesting look. Honestly, I didn’t see it at first. I thought Mankiewicz had lost his mind—casting a blond woman as an Egyptian lady-in-waiting. But she has this quality . . .” Michael Deane leaned in. “And I’m not just talking tits here. There’s something else . . . an authenticity. She’s a real actress, that one.” Deane shook off this thought and looked back at the top photo. “We’ll have to reshoot the scenes with Dee in them. There aren’t many. What with the delays, the rains, the labor stuff, then Liz got sick, and then Dee got sick. When I sent her away, she told me she was disappointed that no one would ever know she was in this movie. So I thought she would want these.” Michael Deane shrugged. “Of course, that was when she thought she was dying.”

It hung in the air, the word dying.

“You know,” Michael Deane said, “I sort of imagined that she’d eventually call me and we’d laugh about this. That it would be a funny story that two people share years later, maybe we’d even . . .” He trailed off, smiled wanly. “But that’s not going to happen. She’s going to want my balls. But please . . . tell her that once she’s over her anger, if she remains cooperative, I’ll get her all the film work she wants when we all get back to the States. Could you tell her that? She could be a star if she wants to be.”

Pasquale felt like he might be sick. He was trying so hard not to hit Michael Deane again—wondering what kind of man abandons a pregnant woman—when a realization came to him, so obvious that it hit him square in the chest, and he gasped. He’d never had a thought as physical as this one, like a kick to his gut: Here I am, angry at this man for abandoning a pregnant woman . . .

While my own son is raised believing that his mother is his sister.

Pasquale flushed. He remembered crouching on the machine-gun nest and saying to Dee Moray: It is not always that simple. But it was. It was entirely simple. There was one kind of man who ran from such responsibility. He and Michael Deane were such men. He could no more hit this man than he could hit himself. Pasquale felt the sickness of his own hypocrisy and covered his mouth.

When Pasquale said nothing, Michael Deane glanced back at the Fontana della Barcaccia and frowned. “This is the world, I guess.”

And then Michael Deane walked away, into the crowd, leaving Pasquale leaning against the fountain. He opened the heavy envelope. It was filled with more money than he’d ever seen—a stack of American currency for Dee and Italian lire for him.

Pasquale put the photos in the envelope and closed it. He looked all around. The day was overcast. People were spread all over the Spanish Steps, resting, but in the piazza and on the street they moved with purpose, at different speeds but in straight lines, like a thousand bullets fired at a thousand different angles from a thousand different guns. All of these people moving in the way they thought right . . . all of these stories, all of these weak, sick people with their betrayals and their dark hearts—This is the world—swirling all around him, speaking and smoking and snapping photographs, and Pasquale felt himself turn hard, and he thought he might spend the rest of his life standing here, like the old fountain of the stranded boat. People would point to the statue of the poor villager who had naively come to the city to talk to the American movie people, the man who had been frozen in time when his own weak character was revealed to him.

And Dee! What was he going to tell her? Would he assail the character of this man she loved, this snake Deane, when Pasquale himself was a species of the same snake? Pasquale covered his mouth as a groan came out.

He felt a hand on his shoulder just then. Pasquale turned. It was a woman, the interpreter who had moved down the line of centurion extras earlier in the day. “You’re the man who knows where Dee is?” she asked in Italian.

“Yes,” Pasquale said.

The woman looked around and then squeezed Pasquale’s arm. “Please. Come with me. There is someone who would like very much to talk to you.”