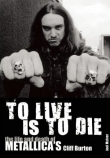

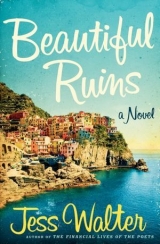

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

14

The Witches of Porto Vergogna

April 1962

Porto Vergogna, Italy

Pasquale slept through the next morning. When he finally woke, the sun had already crested the cliffs behind the town. He climbed the stairs to the third floor and the dark room where Dee Moray had stayed. Had she really just been here? Had he really been in Rome just yesterday, driving with the maniac Richard Burton? It felt as if time had shifted, warped. He looked around the small stone-walled room. It was all hers now. Other guests would stay here, but this would always be Dee Moray’s room. Pasquale threw open the shutters and light poured in. He took a deep breath, but smelled only sea air. Then he picked up Alvis Bender’s unfinished book from the nightstand and thumbed through the pages. Any day now, Alvis would show up to resume writing in that room. But the room would never belong to him again.

Pasquale returned to his room on the second floor and got dressed. On his desk he saw the photograph of Dee Moray and the other laughing woman. He picked it up. The photo didn’t begin to capture Dee’s sheer presence, not the way he remembered it: her graceful height and the long rise of her neck and deep pools of those eyes, and the quality of movement that seemed so different from other people, lithe and energetic, no wasted action. He held the photo close to his face. He liked the way Dee was laughing in the picture, her hand on the other woman’s arm, both of them just beginning to double over. The photographer had caught them at a real moment, breaking up in laughter over something no one else would ever know. Pasquale carried the photo downstairs and slid it into the corner of a framed painting of olives in the tiny hallway between the hotel and the trattoria. He imagined showing his American guests the photo and then feigning nonchalance: sure, he would say, film stars occasionally stayed at the Adequate View. They liked the quiet. And the cliff tennis.

He stared into the photo and thought about Richard Burton again. The man had so many women. Was he even interested in Dee? He would take her to Switzerland for the abortion, and then what? He would never marry her.

And suddenly he had a vision of himself going to Portovenere, knocking on her hotel room door. Dee, marry me. I will raise your child as my own. It was ridiculous—thinking that she would marry someone she’d just met, that she would ever marry him. And then he thought of Amedea and was filled with shame. Who was he to think badly of Richard Burton? This is what happens when you live in dreams, he thought: you dream this and you dream that and you sleep right through your life.

He needed coffee. Pasquale went into the small dining room, which was full of late-morning light, the shutters thrown open. It was unusual for this time of day; his Aunt Valeria waited for the late afternoon to open the shutters. She was sitting at one of the tables, drinking a glass of wine. That was odd for eleven in the morning, too. She looked up. Her eyes were red. “Pasquale,” she said, her voice cracking. “Last night . . . your mother—” She looked at the floor.

He rushed past her to the hall and pushed open Antonia’s door. The shutters and windows were open in here, too, sea air and sunlight filling the room. She lay on her back, a bouquet of gray hair on the pillow behind her, mouth twisted slightly open, a bird’s hooked beak. The pillows were fluffed behind her head, the blanket pulled neatly to her shoulders and folded once, as if already prepared for the funeral. Her skin was waxy, as if it had been scrubbed.

The room smelled like soap.

Valeria was standing behind him. Had she discovered her sister dead . . . and then cleaned the room? It made no sense. Pasquale turned to his aunt. “Why didn’t you tell me this last night, when I got back?”

“It was time, Pasquale,” Valeria said. Tears slid through the scablands of her old face. “Now you can go marry the American.” Valeria’s chin fell to her chest, like an exhausted courier who has delivered some vital message. “It was what she wanted,” the old woman rasped.

Pasquale looked at the pillows behind his mother and at the empty cup on her bedside table. “Oh, Zia,” he said, “what have you done?”

He lifted her chin and in her eyes he could see the whole thing: The two women listening at the window while he talked to Dee Moray, understanding none of it; his mother insisting—as she had for months—that it was her time to die, that Pasquale needed to leave Porto Vergogna to find a wife; his Aunt Valeria making one last desperate attempt, when she’d tried to get the sick American woman to stay, with her witch’s story about how no one ever died young here; his mother asking Valeria over and over (“Help me, Sister”), begging her, hectoring—

“No, you didn’t—”

Before he could finish, Valeria slumped to the ground. And Pasquale turned with disbelief toward his dead mother. “Oh, Mamma,” Pasquale said simply. It was all so pointless, so ignorant; how could they misconstrue so completely what was happening around them? He turned to his sobbing aunt, reached down, and took her face between his hands. He could barely see her dark, wrinkled skin through the blur of his own tears.

“What . . . did you do?”

Then Valeria told him everything: how Pasquale’s mother had been asking for release ever since Carlo died and had even tried to suffocate herself with a pillow. Valeria had talked her out of it, but Antonia persisted until Valeria promised her that, when her older sister could stand the pain no more, she would help. This week, she had called in this solemn promise. Again, Valeria said no, but Antonia said that she could never understand because she wasn’t a mother, that she wanted to die rather than burden Pasquale anymore, that he would never leave Porto Vergogna so long as she was alive. So Valeria did as she’d asked, baked some lye into a loaf of bread. Then Antonia had Valeria leave the hotel for an hour, so that she would have no part in her sin. Valeria tried once more to talk her out of it, but Antonia said she was at peace, knowing that if she went now, Pasquale could go off with the beautiful American—

“Listen to me,” Pasquale said. “The American girl? She loves the other man who was here, the British actor. She doesn’t care about me. This was for nothing!” Valeria sobbed again and fell against his leg, and Pasquale stared down at her bucking, thrashing shoulders, until pity overwhelmed him. Pity, and love for his mother, who would have wanted him to do what he did next: he patted Valeria’s wiry nest of hair and said, “I’m sorry, Zia.” He looked back at his mother, lying against the fluffed pillows, as if in solemn approval.

Valeria spent the day in her room, weeping, while Pasquale sat on the patio smoking and drinking wine. At dusk he went with Valeria and wrapped his mother tight in a sheet and a blanket, Pasquale giving one last gentle kiss to her cold forehead before covering her face. What man ever really knows his mother? She’d had an entire life before him, including two other sons, the brothers he’d never known. She’d survived losing them in the war, and losing her husband. Who was he to decide that she wasn’t ready, that she should linger here a bit longer? She was done. Perhaps it was even good that his mother believed he would run off with some beautiful American when she was gone.

The next morning, Tomasso the Communist helped Pasquale carry Antonia’s body to his boat. Pasquale hadn’t noticed how frail his mother had gotten until he had to carry her this way, his hands beneath her bony, birdlike shoulders. Valeria peeked out from her doorway and said a quiet good-bye to her sister. The other fishermen and their wives lined the piazza and gave Pasquale their condolences—“She’s with Carlo now,” and “Sweet Antonia,” and “God rest”—and Pasquale gave them a small nod from the boat as Tomasso once again pulled the boat motor to life and chugged them out of the cove.

“It was her time,” Tomasso said as he steered through the dark water.

Pasquale faced forward to keep from having to talk anymore, from having to see his mother’s shrouded body. He felt grateful at the way the salty chop stung his eyes.

In La Spezia, Tomasso got a cart from the wharf watchman. He pushed Pasquale’s mother’s body through the street—like a sack of grain, Pasquale thought shamefully—until they finally arrived at the funeral home, and he made arrangements to have her buried next to his father as soon as a funeral mass could be arranged.

Then he went to see the cross-eyed priest who had presided at his father’s mass and burial. Already overwhelmed with confirmation season, the priest said he couldn’t possibly say a requiem mass until Friday, two days from now. How many people did Pasquale expect at the service? “Not many,” he said. The fishermen would come if he asked them; they would spit-flatten their thin hair, put on black coats, and stand with their serious wives while the priest intoned—Antonia, requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine—and afterward, the serious wives would bring food to the hotel. But the whole thing seemed to Pasquale so predictable, so earthbound and pointless. Of course it was exactly what she would have wanted, and so he made arrangements for the funeral mass, the priest making a notation on a ledger of some kind and looking up through his bifocals. And did Pasquale also want him to say trigesimo, the mass thirty days after the death to give the departed a final nudge into heaven? Fine, Pasquale said.

“Eccellente,” Father Francisco said, and held out his hand. Pasquale took the hand to shake it, but the priest looked at him sternly—or at least one of his eyes did. Ah, Pasquale said, and he reached in his pocket and paid the man. The money disappeared beneath his cassock and the priest gave him a quick blessing.

Pasquale was in a daze as he walked back to the pier where Tomasso’s boat was moored. He climbed back in the grubby wooden shell. Pasquale felt terrible again that he had transported his mother this way. And then he recalled the strangest moment, almost at random: He was probably seven. He woke from an afternoon nap, disoriented about the time, and came downstairs to find his mother crying and his father comforting her. He stood outside their bedroom door and watched this, and for the first time Pasquale understood his parents as beings apart from him—that they had existed before he’d been alive. That’s when his father looked up and said, “Your grandmother has died,” and he assumed it was his mother’s mother; only later did he learn that it was his father’s mother. And yet he had been comforting her. And his mother looked up and said, “She is the lucky one, Pasquale. She’s with God now.” Something about the memory caused him to tear up, to think again about the unknowable nature of the people we love. He put his face in his hands and Tomasso politely turned away as they motored away from La Spezia.

Back at the Adequate View, Valeria was nowhere to be found. Pasquale looked in her room, which was as cleaned and made up as his mother’s had been—as if no one had ever been there. The fishermen hadn’t taken her away; she must have hiked out on the steep trails behind the village. That night, the hotel felt like a crypt to Pasquale. He grabbed a bottle of wine from his parents’ cellar and sat in the empty trattoria. The fishermen all stayed away. Pasquale had always felt confined by his life—by his parents’ fearful lifestyle, by the Hotel Adequate View, by Porto Vergogna, by these things that seemed to hold him in place. Now he was chained only to the fact that he was completely alone.

Pasquale finished the wine and got another bottle. He sat at his table in the trattoria, staring at the photo of Dee Moray and the other woman, as the night bled out and he became drunk and dizzy, and still his aunt didn’t return, and at some point he must have fallen asleep, because he heard a boat and then the voice of God bellowed through his hotel lobby.

“Buon giorno!” God called. “Carlo? Antonia? Where are you?” And Pasquale wanted to weep, because shouldn’t they be with God, his parents? Why was He asking for them, and in English? But finally Pasquale realized he was asleep and he lurched into consciousness, just as God switched back to Italian: “Cosa un ragazzo deve fare per ottenere una bevanda qui intorno?” and Pasquale realized that, of course, it wasn’t God. Alvis Bender was in his hotel lobby first thing this morning, here for his yearly writing vacation, and asking in his sketchy Italian, What’s a fella got to do to get a drink around here?

After the war, Alvis Bender had been lost. He returned to Madison to teach English at Edgewood, a little liberal arts college, but he was sullen and rootless, prone to weeks of drunken depression. He felt none of the passion he’d once had for teaching, for the world of books. The Franciscans who ran the college tired quickly of his heavy drinking and Alvis went back to work for his father. By the early fifties, Bender Chevrolet was the biggest dealership in Wisconsin; Alvis’s father had opened new showrooms in Green Bay and Oshkosh, and was about to open a Pontiac dealership in suburban Chicago. Alvis made the most of his family’s prosperity, behaving in the auto business as he had at his little college and earning the nickname All Night Bender among the dealership secretaries and bookkeepers. The people around Alvis attributed his mood swings to what was euphemistically called “battle fatigue,” but when his father asked Alvis if he was shell-shocked, Alvis said, “I get shelled every day at happy hour, Dad.”

Alvis didn’t think he had battle fatigue—he’d barely seen combat—so much as life fatigue. He supposed it could be some kind of postwar existential funk, but the thing eating him felt smaller than that: he just no longer saw the point of things. He especially couldn’t see the angle in working hard, or in doing the right thing. After all, look where that had got Richards. Meanwhile, he’d survived to come back to Wisconsin and—what? Teach sentence diagramming to morons? Sell Bel Airs to dentists?

On his better days he imagined that he could channel this malaise into the book he was writing—except that he wasn’t actually writing a book. Oh, he talked about the book he was writing, but the pages never came. And the more he talked about the book he wasn’t writing, the harder it actually became to write. The first sentence bedeviled him. He had an idea that his war book would be an antiwar book; that he would focus on the drudgery of soldiering and his book would feature only a single battle, the nine-second firefight at Strettoia in which his company had lost two men; that the entire thing would be about the boredom leading up to those nine seconds; that in those nine seconds the protagonist would die, and then the book would go on anyway, with another, more minor character. This structure seemed to him to capture the randomness of what he’d experienced. All the World War II books and movies were so damned earnest and solemn, Audie Murphy stories of bravery. His own callow view, he felt, fit more with books about the first world war: Hemingway’s stoic detachment, Dos Passos’s ironic tragedies, Céline’s absurd black-hearted satires.

Then, one day, as he was trying to coax a woman he’d just met into sleeping with him, he happened to mention that he was writing a book, and she became intrigued. “About what?” she asked. “It’s about the war,” he answered. “Korea?” she asked, innocently enough, and Alvis realized just how pathetic he’d become.

His old friend Richards was right: they’d gone ahead and started another war before Alvis had finished with the last one. And just thinking about his dead friend made Alvis properly ashamed of how he’d wasted the last eight years.

The next day, Alvis marched into the showroom and announced to his father that he needed some time off. He was returning to Italy; he was finally going to write his book about the war. His father wasn’t happy, but he made Alvis a deal: he could take three months off, as long as he came back to run the new Pontiac dealership in Kenosha when he was through. Alvis quickly agreed.

And so he went to Italy. From Venice to Florence, from Naples to Rome, he traveled, drank, smoked, and contemplated, and everywhere he went he packed his portable Royal—without ever removing it from the case. Instead, he’d check into a hotel and go straight to the bar. Everywhere he went, people wanted to buy a returning GI a drink, and everywhere he went, Alvis wanted to accept. He told himself he was doing research, but except for an unproductive trip to Strettoia, the site of his tiny firefight, most of his research involved drinking and trying to seduce Italian girls.

In Strettoia, he woke terribly hung over and went for a walk, looking for the clearing where his old unit had gotten into the firefight. There, he came across a landscape painter doing a sketch of an old barn. But the young man was drawing the barn upside down. Alvis thought maybe there was something wrong with the man, some sort of brain damage, and yet there was a quality to his work that drew Alvis in, a disorientation that seemed familiar.

“The eye sees everything upside down,” the artist explained, “and then the brain automatically reverses it. I’m just trying to put it back the way the mind sees it.”

Alvis stared into the drawing for a long time. He even thought about buying it, but he realized that if he hung it this way, upside down, people would just turn it over. This, he decided, was also the problem with the book he hoped to write. He could never write a standard war book; what he had to say about the war could only be told upside down, and then people would probably just miss the point and try to turn it right side up again.

That night, in La Spezia, he bought a drink for an old partisan, a man with horrible burn scars on his face. The man kissed Alvis’s cheeks and smacked his back and called him “comrade” and “amico!” He told Alvis the story of how he’d gotten those burns: his partisan unit had been sleeping in a haystack in the hills when, without warning, a German patrol used a flamethrower to roust them. He was the only one to escape alive. Alvis was so moved by the man’s story that he bought him several rounds of drinks, and they saluted each other and wept over friends they had lost. Finally, Alvis asked the man if he could use his story in the book he was writing. This caused the Italian to begin weeping. It was all a lie, the Italian confessed; there had been no partisan unit, no flamethrower, no Germans. The man had been working on a car two years earlier when the engine had suddenly caught fire.

Moved by the man’s confession, Alvis Bender drunkenly forgave his new friend. After all, he was a fraud, too; he’d talked about writing a book for ten years and hadn’t written a single word. The two drunken liars hugged and cried, and stayed up all night confessing their weak hearts.

In the morning, a dreadfully hungover Alvis Bender sat staring at the port of La Spezia. He only had two weeks left of the three months his father had given him to “figure this shit out.” He grabbed his suitcase and his portable typewriter, trudged down to the pier, and started negotiating a boat ride to Portovenere, but the pilot misheard his slurred Italian. Two hours later, the boat bumped into a rocky promontory in a closet-size cove, where he laid eyes on a runt of a town, maybe a dozen houses in all, clinging to the rocky cliffs, surrounding a single sad business, a little pensione and trattoria named, like everything on that coast, for St. Peter. There were a handful of fishermen tending nets in little skiffs and the owner of the empty hotel sat on his patio reading a newspaper and smoking a pipe, while his handsome, azure-eyed son sat daydreaming on a nearby rock. “What is this place?” Alvis Bender asked, and the pilot said, “This is Porto Vergogna.” Port of Shame. Wasn’t that where he’d wanted to go? And Alvis Bender could think of no better place for himself and said, “Yes, of course.”

The proprietor of the hotel, Carlo Tursi, was a sweet, thoughtful man who had left Florence and moved to the tiny village after losing his two older sons in the war. He was honored to have an American writer stay in his pensione, and he promised that his son, Pasquale, would be quiet during the day so Alvis could work. And so it was that in the tiny top-floor room, with the gentle wash of waves on the rocks below, Alvis Bender finally unpacked his portable Royal. He put the typewriter on the nightstand beneath the shuttered window. He stared at it. He slipped a sheet of paper in, cranked it through. He put his hands on the keys. He rubbed their smooth-pebbled surfaces, the lightly raised letters. And an hour passed. He went downstairs for some wine and found Carlo sitting on the patio.

“How is the writing?” Carlo asked solemnly.

“Actually, I’m having some trouble,” Alvis admitted.

“With which part?” Carlo asked.

“The beginning.”

Carlo considered this. “Perhaps you could write first the ending.”

Alvis thought about the upside-down painting he’d seen near Strettoia. Yes, of course. The ending first. He laughed.

Thinking the American was laughing at his suggestion, Carlo apologized for being “stupido.”

No, no, Alvis said, it was a brilliant suggestion. He’d been talking and thinking about this book for so long—it was as if it already existed, as if he’d already written it in some way, as if it was just out there, in the air, and all he had to do was find a place to tap into the story, like a stream flowing by. Why not start at the end? He ran back upstairs and typed these words: “Then spring came and with it the end of my war.”

Alvis stared at his one sentence, so odd and fragmented, so perfect. Then he wrote another sentence and another, and soon he had a page, at which point he ran down the stairs and had a glass of wine with his muse, the serious, bespectacled Carlo Tursi. This would be his reward and his rhythm: type a page, drink a glass of wine with Carlo. After two weeks of this, he had twelve pages. He was surprised to discover that he was telling the story of a girl he’d met near the end of the war, a girl who had given him a quick hand job. He hadn’t planned to even include that story in his book—since it was apropos of nothing—but suddenly it seemed like the only story that mattered.

On his last day in Porto Vergogna, Alvis packed up his few pages and his little Royal and said good-bye to the Tursi family, promising to return next year to work, to spend two weeks each year in the little village until his book was done, even if it took the rest of his life.

Then he had one of the fishermen take him to La Spezia, where he caught a bus to Licciana, the girl’s hometown. He watched out the window of the bus, looking for the place where he’d met her, for the barn and the stand of trees, but nothing looked the same and he couldn’t get his bearings. The village itself was twice as big as it had been during the war, the crumbly old rock buildings replaced by wood and stone structures. Alvis went to a trattoria and gave the proprietor Maria’s last name. The man knew the family. He’d gone to school with Maria’s brother, Marco, who had fought for the Fascists and was tortured for his efforts, hung by his feet in the town square and bled like a butchered cow. The man didn’t know what had become of Maria, but her younger sister, Nina, had married a local boy and lived in the village still. Alvis got directions to Nina’s home, a one-story stone house in a clearing below the old rock walls of the village, in a new neighborhood that was spreading down the hill. He knocked. The door opened a crack and a black-haired woman stuck her face out the window next to the door and asked what he wanted.

Alvis explained that he’d known her sister in the war. “Anna?” the girl asked.

“No, Maria,” Alvis said.

“Oh,” she said, somewhat darkly. After a moment, she invited him into the well-kept living room. “Maria is married to a doctor, living in Genoa.”

Alvis asked if she might have an address for Maria.

Nina’s face hardened. “She doesn’t need another old boyfriend from the war coming back. She is finally happy. Why do you want to make trouble?”

Alvis insisted he didn’t want to make any trouble.

“Maria had a hard time in the war. Leave her be. Please.” And then one of Nina’s children called for her and she went to the kitchen to check on him.

There was a telephone in the living room, and like a lot of people who had only recently gotten a telephone, Maria’s sister kept it in a prominent place, on a table covered with figures of saints. Beneath the phone was an address book.

Alvis reached over, opened the book to the M section, and there it was: the name Maria. No last name. No phone number. Just a street number in Genoa. Alvis memorized the address and closed the book, thanked Nina for her time, and left.

That afternoon, he took a train to Genoa.

The address turned out to be near the harbor. Alvis worried that he’d gotten it wrong; this did not appear to be the neighborhood of a doctor and his wife.

The buildings were brick and stone, built one on top of the other, their heights like a musical scale descending gradually to the harbor. The ground floors were filled with cheap cafés and taverns that catered to fishermen, while above were flop apartments and simple hotels. Maria’s street number led to a tavern, a rotted-wood rat-hole of a place with warped tables and a ragged old rug. A rail-thin, smiling barman sat behind the counter, serving fishermen in droopy caps bent over chipped glasses of amber.

Alvis apologized, said he must have the wrong place. “I’m looking for a woman—” he began.

The skinny bartender didn’t wait for a name. He just pointed to the stairs behind the bar and held out his hand.

“Ah.” Knowing exactly where he was now, Alvis paid the man. As he climbed the stairs, he prayed there was some mistake, that he wouldn’t find her here. At the top was a hallway that opened into a foyer with a couch and two chairs. Sitting on the couch, talking in low voices, were three women in nightgowns. Two of the three were young—girls, really, in short nighties, reading magazines. Neither of them looked familiar.

In the other chair, a faded silk robe over her nightgown, smoking the last of a cigarette, sat Maria.

“Hello,” Alvis said.

Maria didn’t even look up.

One of the younger girls said, in English, “America, yes? You like me, America?”

Alvis ignored the younger girl. “Maria,” he said quietly.

She didn’t look up.

“Maria?”

Finally, she glanced up. She seemed twenty years older, not ten. A thickening had occurred in her arms and there were lines around her mouth and eyes.

“Who’s Maria?” she asked in English.

One of the other girls laughed. “Stop teasing him. Or give him to me.”

With no trace of recognition in her voice, Maria gave Alvis the prices, in English, for various amounts of time. Above her was an awful painting of an iris. Alvis fought the urge to turn it upside down. He bought a half hour.

No stranger to this kind of place, he paid Maria half the agreed-upon price, which she folded and took downstairs to the man behind the bar. Then Alvis followed her down the hall to a small room. Inside, there was nothing but a made bed, a nightstand, a coat rack, and a scratched, foggy mirror. A window looked out on the harbor and the street below. She sat down on the bed, its springs creaking, and began to undress.

“You don’t remember me?” Alvis asked in Italian.

She stopped undressing and sat on the bed, unmoved, no recognition in her eyes.

Alvis began slowly, telling her in Italian how he’d been stationed in Italy during the war, how he’d met her on a deserted road and walked her home one night, how on the day he met her he’d reached a point where he didn’t care if he lived or died, but that after meeting her he had cared again. He said that she’d encouraged him to write a book after the war, to take it seriously, but that he’d gone home to America (“Ricorda—Wisconsin?”) and drank away the last decade. His best friend, he said, had died in the war, leaving behind a wife and a son. Alvis had no one, and he’d come home and wasted all of those years.

She listened patiently and then asked if he wanted to have sex.

He told her that he had gone to Licciana to look for her, and he thought he saw something in her eyes when he said the name of the village—shame, perhaps—because he had been so humbled by what she did for him that night: not the part with her hand, but the way she’d comforted him afterward, held his crying face against her beautiful chest. That was, he said, the most humane thing anyone had ever done for him.

“I’m so sorry,” Alvis said, “that you became this.”

“This?” She startled Alvis by laughing. “I’ve always been this.” She waved at the room around her and said, in a flat Italian, “Friend, I don’t know you. And I don’t know this village you speak of. I’ve always lived in Genoa. I get boys like you sometimes, American boys who were in the war and had their first sex with a girl who looked like me. It’s fine.” She looked patient, but not particularly interested in his story. “But what were you going to do, rescue this Maria? Take her back to America?”

Alvis could think of nothing to say. No, of course he wasn’t going to take her back to America. So what was he going to do? Why was he here?

“You made me happy, choosing me over the younger girls,” the prostitute said, and she reached out for his belt. “But please. Stop calling me Maria.”

As her hands expertly undid his belt, Alvis stared at the woman’s face. It had to be her, didn’t it? And now, suddenly, he wasn’t so sure. She did seem older than Maria should. And the thickening he’d attributed to age—could this actually be someone else? Was he confessing to some random whore?

He watched her thick hands unbutton his pants. He felt paralyzed, but he managed to pull himself away. He buttoned his pants and cinched his belt again.