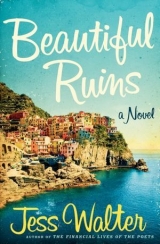

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

18

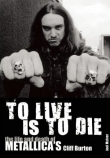

Front Man

Recently

Sandpoint, Idaho

At 11:14 A.M., the doomed Deane Party departs LAX on the first leg of its epic journey, taking up an entire first-class row on the Virgin Airlines direct flight to Seattle. In 2A, Michael Deane stares out his window and fantasizes this actress looking exactly as she did fifty years ago (and himself, too), imagines her forgiving him instantly (Water under the bridge, darling). In 2B, Claire Silver glances up occasionally from the excised opening chapter of Michael Deane’s memoir in whispered awe (No way . . . Richard Burton’s kid?). The story is so matter-of-factly disturbing that it should instantly seal her decision to take the cult museum job, but her repulsion gives way to compulsion, then curiosity, and she flips the typewritten pages faster and faster, oblivious to the fact that Shane Wheeler is casually tossing unsubtle negotiating gambits across the aisle from 2C (I don’t know; maybe I should shop Donner! around . . .). Seeing Claire immersed in whatever document Michael Deane gave her, Shane begins to worry that it’s another script, perhaps one even more outlandish than his Donner! pitch, and quickly abandons his coy negotiating tactics. He turns away, to old Pasquale Tursi in 2D, makes polite conversation (“È sposato?” Are you married? “Sì, ma mia moglie è morta.” Yes, but my wife is dead. “Ah. Mi dispiace. Figli?” I’m sorry. Any children? “Sì, tre figli e sei nipoti.” Three children, six grandchildren). Talking about his family makes Pasquale feel embarrassed about the silly, old-man sentimentality of this late-life indulgence: acting like a lovesick boy off chasing some woman he knew for all of three days. Such folly.

But aren’t all great quests folly? El Dorado and the Fountain of Youth and the search for intelligent life in the cosmos—we know what’s out there. It’s what isn’t that truly compels us. Technology may have shrunk the epic journey to a couple of short car rides and regional jet legs—four states and twelve hundred miles traversed in an afternoon—but true quests aren’t measured in time or distance anyway, so much as in hope. There are only two good outcomes for a quest like this, the hope of the serendipitous savant—sail for Asia and stumble on America—and the hope of scarecrows and tin men: that you find out you had the thing you sought all along.

In the Emerald City the tragic Deane Party changes planes, Shane ever so casually mentioning that the ground they’ve covered so far in just over two hours would’ve taken William Eddy months to travel.

“And we haven’t even had to eat anyone,” Michael Deane says, and then adds, more ominously than he intends, “yet.”

For the final leg they pack into a commuter prop-job, a toothpaste tube of returning college freshmen and regional sales associates. It’s a mercifully brief flight: ten minutes taxiing, ten minutes climbing over a bread-knife set of mountains, ten more over a grooved desert, another ten over patchwork farmland, then a curtain of clouds parts and they bank over a stubby, pine-ringed city. At three thousand feet, the pilot sleepily and prematurely welcomes them to Spokane, Washington, ground temperature fifty-four.

Wheels on the ground, Claire notes that six of her eight cell-phone calls and text messages are from Daryl, who has now gone thirty-six hours without talking to his girlfriend and finally suspects something is amiss. The first text reads R U mad. The second, Is it the strippers. Claire puts her phone away without reading the rest.

They straggle from the Jetway through a tidy, bright airport that looks like a clean bus station, past electronic ads for Indian casinos, photos of streams and old brick buildings, and signs welcoming them to something called “the Inland Northwest.” They make a strange group: old Pasquale in a dark suit and hat, with a cane, like he’s slipped from a black-and-white movie; Michael Deane looking like a different time-travel experiment, a shuffling, baby-faced grandpa; Shane, now worried that he’s overplayed his hand, constantly riffling his hair, muttering apropos of nothing: “I’ve got other ideas, too.” Only Claire has weathered the journey well, and this reminds Shane of William Eddy’s Forlorn Hope: it was those women, too, who made the passage with some of their strength intact.

Outside, the afternoon sky is chalky, air crackling. No sign of the city they flew over, just trees and basalt stumps surrounding airport parking garages.

Michael’s man Emmett has a private investigator waiting for them, a thin balding man in his fifties leaning on a dirty Ford Expedition. He’s wearing a heavy coat over a suit jacket and holding a sign that doesn’t inspire much confidence: MICHAEL DUNN.

They approach and Claire asks, “Michael Deane?”

“About the old actress, yeah?” The investigator barely looks at Michael’s strange face—as if he’s been warned not to stare. He introduces himself as Alan, retired cop and private investigator. He opens the doors for them and loads their bags. Claire slides in back between Michael and Pasquale and Shane jumps in front next to the investigator.

Inside the SUV, Alan hands them a file. “I was told this was top-priority stuff. It’s pretty solid work for twenty-four hours, if I do say so myself.”

The file goes to the back and Claire takes charge of it, quickly flipping past a birth certificate and newspaper birth notice from Cle Elum, Washington. “You said she was about twenty in 1962,” the investigator says to Michael, whom he eyes in the rearview, “but her actual DOB is late ’39. No surprise there. Two kinds of people always lie about their ages: actresses and Latin American pitchers.”

Claire flips to the second page of the file—Michael looking over one shoulder, Pasquale the other—a photocopy of a 1956 yearbook page from Cle Elum High School. She’s easy to spot: the striking blonde with the oversized features of a born actress. Beside her, the two pages of senior class photos are a festival of black-rims and cowlicks, of beady eyes, jug ears, crew cuts, acne, and beehives. Even in black-and-white, Debra Moore fairly jumps, her eyes simply too big and too deep for this little school and little town. Beneath her photo: “DEBRA ‘DEE’ MOORE: Warrior Cheer Squad—3 years, Kittitas County Fair Princess, Musical Theater—3 years, Senior Showcase, Honors—2 years.” Each student has also chosen a famous quote (Lincoln, Whitman, Nightingale, Jesus), but Debra Moore’s quote is from Émile Zola: I am here to live out loud.

“She’s in Sandpoint now,” the investigator is saying. “Hour and a half away. Pretty drive. She runs a little theater up there. There’s a play tonight. I got you four tickets at will-call and four hotel rooms. I’ll drive you back tomorrow afternoon.” The SUV merges onto a freeway, descends a steep hill into Spokane: a downtown of low brick, stone, and glass buildings, pocked with billboards and surface parking lots, all of it loosely bisected by this freeway overpass.

They read as they ride, much of the file consisting of playbills and cast lists: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, put on by the University of Washington drama department in 1959, listing “Dee Anne Moore” as Helena. She pops in every photograph, as if everyone else is frozen flat in the 1950s and here, suddenly, is a modern, animated woman.

“She’s beautiful,” Claire says.

“Yes,” says Michael Deane over her right shoulder.

“Sì,” says Pasquale over her left.

Theater reviews clipped from the Seattle Times and the Post-Intelligencer praise “Debra Moore” briefly in various stage roles in 1960 and 1961, the investigator’s yellow-highlighter pen framing “talented newcomer” and “the show-stopping Dee Moore.” Next come two photocopied Seattle Times articles from 1967, the first about a single-fatality car accident, the second an obituary for the driver, Alvis James Bender.

Before Claire can figure out the connection to Dee Moray, Pasquale takes the page, leans forward, and presses it into the hands of Shane Wheeler in the front seat. “This one? What is it?”

Shane reads the small obituary. Bender was a World War II army veteran and owner of a Chevrolet car dealership in North Seattle. He moved to Seattle in 1963, just four years before his death. He was survived by his parents in Madison, Wisconsin, a brother and sister, several nieces and nephews, his wife, Debra Bender, and their son, Pat Bender of Seattle.

“They were married,” Shane tells Pasquale. “Sposati. This was Dee Moray’s husband—il marito. Morto, incidente di macchina.”

Claire looks over. Pasquale has gone white. He asks when. “Quando?”

“Nel sessantasette.”

“Tutto questo è pazzesco,” Pasquale mutters. This is all crazy. He says nothing more, just slumps back in his seat, hand rising slowly to his mouth. He seems to have no more interest in the file and he stares out the window at the strip-mall sprawl, much the way he stared out the window on the plane earlier.

Claire looks from Shane to Pasquale and back. “Did he expect her never to get married? Fifty years . . . that’s asking a lot.” Pasquale says nothing.

“Have you ever thought about a TV show where you fix people up with their old high school flames?” Shane asks Michael Deane, who ignores the question.

The next pages in the file are a 1970 graduation announcement from Seattle University (a bachelor’s degree in education and Italian), obituaries for Debra Moore’s parents, probate documents, tax forms for a house she sold in 1987. A much newer high school yearbook shows a 1976 black-and-white staff photo from Garfield High identifying her as “Mrs. Moore-Bender: Drama, Italian.” She seems to get more attractive in every photo, her face sharpening—or perhaps it’s just in comparison with other teachers, all those dull-eyed men in fat ties and uneven sideburns, lumpy women with close haircuts and cat’s-eye glasses. In the Drama Club photo she poses at the center of a mugging, expressive group of shaggy-haired students—a tulip in a field of weeds.

The next page in the file is another photocopied newspaper story, from the Sandpoint Daily Bee, circa 1999, saying that “Debra Moore, a respected drama teacher and community theater director from Seattle, is taking over as artistic director of Theater Arts Group of Northern Idaho,” that she “hopes to augment the usual slate of comedies and musicals with some original plays.”

The file concludes with a few pages about her son, Pasquale “Pat” Bender; these pages are broken into two categories—traffic and criminal charges (DUIs and possession charges, mostly) and newspaper and magazine stories about the various bands he fronted. Claire counts at least five—the Garys, Filigree Handpipe, Go with Dog, the Oncelers, and the Reticents, this last outfit the most successful, signed by the Seattle record label Sub Pop, for whom they produced three albums in the 1990s. Most of the stories are from small alternative newspapers, concert and album reviews, stories about the band having a CD release party or canceling a show, but there is also a capsule review from Spin, of a CD called Manna, a record the magazine gives two stars, alongside this description: “ . . . when Pat Bender’s intense command of the stage translates to the studio, this Seattle trio can sound rich and playful. But too often on this effort, he sounds uninterested, as if he showed up to the recording session wasted, or—worse for this cult favorite—sober.”

The last pages of the file are listings in the Willamette Weekly and The Mercury for Pat Bender’s solo shows in several clubs in the Portland area in 2007 and 2008, and a short piece from the Scotsman, a newspaper in Scotland, with a scathing review of something called Pat Bender: I Can’t Help Meself!

And that’s it. They read different sheets from the file, trade them, and finally look up to find that they’re on the expanding edge of the city now, clusters of new houses cut into the slabs of basalt and heavy timber. To have a life reduced like that to some loose sheets of paper: it feels a little profane, a little exhilarating. The investigator is tapping a song on the steering wheel that only he hears. “Almost to the state line.”

The Deane Party’s epic trek is nearing its completion now, a single border left to cross—four unlikely travelers compelled along in a vehicle sparked on the gaseous fuel of spent life. They can cover sixty-seven miles in an hour, fifty years in a day, and the speed feels unnatural, untoward, and they look out their separate windows at the blurring sprawl of time, as for two miles, for nearly two minutes, they are quiet, until Shane Wheeler says, “Or what about a show about girls with anorexia?”

Michael Deane ignores the translator, leans forward toward the front seat, and says, “Driver, anything you can tell us about this play we’re going to see?”

FRONT MAN

Part IV of the Seattle Cycle

A Play in Three Acts

by Lydia Parker

DRAMATIS PERSONAE:

PAT, an aging musician

LYDIA, a playwright and Pat’s girlfriend

MARLA, a young waitress

LYLE, Lydia’s stepfather

JOE, a British music promoter

UMI, a British club girl

LONDONER, a passing businessman

CAST:

PAT: Pat Bender

LYDIA: Bryn Pace

LYLE: Kevin Guest

MARLA/UMI: Shannon Curtis

JOE/LONDONER: Benny Giddons

The action takes place between 2005 and 2008, in Seattle, London, and Sandpoint, Idaho.

ACT I

Scene I

[A bed in a cramped apartment. Two figures are entangled in the sheets, Pat, 43, and Marla, 22. It’s dimly lit; the audience can see the figures but can’t quite make out their faces.]

Marla: Huh.

Pat: Mm. That was great. Thanks.

Marla: Oh. Yeah. Sure.

Pat: Look, I don’t mean to be an ass, but do you think we could get dressed and get out of here?

Marla: Oh. Then . . . that’s it?

Pat: What do you mean?

Marla: Nothing. It’s just—

Pat: [laughing] What?

Marla: Nothing.

Pat: Tell me.

Marla: It’s just . . . so many girls in the bar have talked about sleeping with you. I started to think there was something wrong with me that I hadn’t done it with the great Pat Bender. Then, when you came in alone tonight, I thought, well, here’s my chance. I guess I just expected it to be . . . I don’t know . . . different.

Pat: Different . . . than what?

Marla: I don’t know.

Pat: ’Cause that’s pretty much the way I’ve always done it.

Marla: No, it was fine.

Pat: Fine? This just gets better and better.

Marla: No, I guess I just bought into the whole womanizer thing. I assumed you knew things.

Pat: What . . . things?

Marla: I don’t know. Like . . . techniques.

Pat: Techniques? Like what? Levitation? Hypnosis?

Marla: No, it’s just that after all the talk I figured that I’d have . . . you know . . . four or five.

Pat: Four or five what?

Marla: [becomes shy] You know.

Pat: Oh. Well. How many did you have?

Marla: So far, none.

Pat: Well, I’ll tell you what: I owe you a couple. But for now, do you think we could get dressed before—

[A door closes offstage. The whole scene has taken place in near darkness, the only light coming from an open doorway. Now, still in silhouette, Pat pulls the covers over Marla’s head.]

Pat: Oh shit.

[Lydia, 30s, short hair, army cargo pants, Lenin cap, ENTERS. She pauses in the doorway, her face lit by the light from the other room.]

Pat: I thought you were at rehearsal.

Lydia: I left early. Pat, we need to talk.

[She comes in, reaches toward the nightstand to turn on the light.]

Pat: Uh, maybe leave the light off?

Lydia: Another migraine?

Pat: Bad one.

Lydia: Okay. Well, I just wanted to apologize for storming out of the restaurant tonight. You’re right. I do still try to change you sometimes.

Pat: Lydia—

Lydia: No, let me finish, Pat. This is important.

[Lydia walks to the window, stares out, a streetlight casting a glow on her face.]

Lydia: I’ve spent so long trying to “fix” you that I don’t always give you credit for how far we’ve come. Here you are, clean almost two years, and I’m so alert for trouble it’s all I see sometimes. Even when it isn’t there.

Pat: Lydia—

Lydia: [turning back] Please, Pat. Just listen. I’ve been thinking. We should move away. Get out of Seattle for good. Go to Idaho. Be near your mom. I know I said we can’t keep running from our problems, but maybe it makes sense now. Start fresh. Get away from our pasts . . . all this shit with your bands, my mom, and my stepdad.

Pat: Lydia—

Lydia: I know what you’re gonna say.

Pat: I’m not sure you do—

Lydia: You’re gonna say, what about New York? I know we screwed that up. But we were younger then, Pat. And you were still using. What chance did we have? That day I came back to the apartment and saw that you’d pawned all of our stuff it was almost a relief. Here I’d been waiting for the bottom to fall out. And finally it did.

[Lydia turns to the window again.]

Lydia: After that, I told your mom that if you could’ve controlled your addictions, you’d have been famous. She said something I’ll never forget: “But dear. That IS his addiction.”

Pat: Jesus, Lydia—

Lydia: Pat, I left rehearsal early tonight because your mom called from Idaho. I don’t know how to say this, so I’m just going to say it. Her cancer is back.

[Lydia walks over to the bed, sits on Pat’s side.]

Lydia: They don’t think it’s operable. She might have months, or years, but they can’t stop it. She’s going to try chemo again, but they’ve exhausted the radiation possibilities, so all they can do is manage it. But she sounded good, Pat. She wanted me to tell you. She couldn’t bear to tell you herself. She’s afraid you’ll start using again. I told her you were stronger now—

Pat: [whispering] Lydia, please . . .

Lydia: So let’s move, Pat. What do you say, just go? Please? I mean . . . we assume these cycles are endless . . . we fight, break up, make up, our lives circle around and around, but what if it’s not a circle. What if it’s a drain we’re going down? What if we look back and realize we never even tried to break out of it?

[On the bedside, Lydia reaches into the tangle of covers for Pat’s hand. But she feels something, recoils, jumps from the bed, and turns on the light, throwing a harsh light across Pat and the other lump in the bed. She pulls the covers back. Only now do we see the actors in full light. Marla holds the sheet to her chest, gives a little wave. Lydia backs across the room. Pat just stares off.]

Lydia: Oh.

[Pat climbs slowly out of bed to get his clothes. But he stops. He stands there naked, as if noticing himself for the first time. He looks down, surprised that he’s grown so thick and middle-aged. Finally he turns to Lydia, standing in the doorway. The quiet seems to go on forever.]

Pat: So . . . I guess a threesome’s out of the question.

CURTAIN

In the half-empty theater there is a collective gasp, followed by bursts of agitated, uncomfortable laughter. As the stage goes dark, Claire realizes she’s been holding her breath throughout the play’s short opening scene. Now she’s breathed out, and the whole audience with her, a sudden release of tense, guilty laughter at the sight of this cad standing naked on a stage—his crotch subtly and artfully covered by a blanket over the bed’s footboard.

In the darkness of a set change, ghosts linger in Claire’s eyes. She becomes aware of the scene’s clever staging: played mostly in half-light, forcing the audience to search the near-darkness for the figures, so that when the harsh lights finally come up, Lydia’s tortured face and Pat’s white softness are boned into their retinas like X-rays—that poor girl staring at her naked boyfriend, another woman in their bed, a strobe of betrayal and regret.

This wasn’t what Claire was expecting (community theater? in Idaho?) when they arrived in Sandpoint, a funky Old West ski town on the shores of this huge mountain lake. With no time to check into their hotel, the investigator took them straight to the Panida Theater, its lovely vertical descending sign marking a quaint storefront in the small L-shaped downtown, classic old box office opening into a Deco theater—too big for this small, personal play, but an impressive room nonetheless, carefully restored to its old 1920s movie-house past. The back of the theater was empty, but the front seats had a good spread of black-clad small-town hipsters, older Birkenstockers, and fake blondes in ski outfits, even older moneyed couples, which—if Claire knew her small-town theater—would be this theater group’s patrons. Settled in her hard-backed seat, Claire glanced at the photocopied cover of the playbill: FRONT MAN • PREVIEW PERFORMANCE • THEATER ARTS GROUP OF NORTHERN IDAHO. Here we go, she’d thought: amateur hour.

But then the thing starts and Claire is shocked. Shane, too: “Wow,” he whispers. Claire sneaks a glance at Pasquale Tursi, and he appears rapt, although it’s hard to read the look on his face—whether it’s admiration for the play or simple confusion about what that naked man is doing onstage.

Claire glances to her right, at Michael, and his waxen face seems somehow stricken, his hand on his chest. “My God, Claire. Did you see that? Did you see him?”

Yes. There is that, too. It’s undeniable. Pat Bender is some kind of force onstage. She’s not sure if it’s because she knows who his father is, or perhaps because he’s playing himself—but for one quick, delusional moment, she wonders if this might be the greatest actor she’s ever seen.

Then the lights come up again.

It’s a simple play. From that opening scene, the story follows Pat and Lydia out on their parallel journeys. In his, Pat spends three drunken years in the wilderness, trying to tame his demons. He performs a musical-comedy monologue about the bands he used to be in, and about failing Lydia—a show that eventually gets him dragged to London and Scotland by an exuberant young Irish music producer. For Pat the trip smacks of desperation, a misguided final attempt at becoming famous. And it all blows up when Pat betrays Joe by sleeping with Umi, the girl his young friend loves. Joe runs off with Pat’s money and he ends up stranded in London.

In Lydia’s parallel story, her mother dies suddenly and Lydia finds herself stuck caring for her senile stepfather, Lyle, a man she’s never gotten along with. Lyle provides daft comic relief, constantly forgetting that his wife has died, asking the thirty-five-year-old Lydia why she isn’t at school. Lydia wants to move him into a nursing home, but Lyle fights to stay with her, and Lydia can’t quite do it. In a storytelling device that works better than Claire expects, Lydia fills in the gaps and marks the passage of time by talking on the phone to Pat’s mother, Debra, in Idaho. She never appears onstage but is an unseen, unheard presence on the other end of the phone. “Lyle wet the bed today,” Lydia says, pausing for a response from the unseen Debra (or Dee, as she sometimes calls her). “Yes, Dee, it would be natural . . . except it was my bed! I looked up and he was standing on my bed, pissing a hot streak and shouting, ‘Where are the hand towels?’ ”

Finally, Lyle burns himself on the oven while Lydia is at work, and she has no choice but to move him into a nursing home. Lyle cries when she tells him about it. “You’ll be fine,” she insists. “I promise.”

“I’m not worried about me,” Lyle says. “It’s just . . . I promised your mother. I don’t know who will take care of you now.”

In the wake of that realization—that Lyle believes he has been caring for her—Lydia understands that she’s most alive when she’s caring for someone else, and goes to Idaho to take care of Pat’s ailing mother. Then, one night, she’s asleep in Debra’s living room when the phone rings. The lights come up on the other side of the stage—revealing Pat, standing in a red phone booth, calling his mother for help. At first Lydia is excited to hear from him. But all Pat seems to care about is that he’s run out of money and needs help to get home from London. He doesn’t even ask about his mother.

Lydia goes quiet on the other end of the call. “Wait. What time is it there?” he asks. “Three,” Lydia says quietly. And Pat’s head falls to his chest exactly as it did in the first scene.

“Who is it, dear?” comes a voice from offstage—the first words Pat’s mother has spoken in the entire play. In his London phone booth, Pat whispers, “Do it, Lydia.” Lydia takes a deep breath, says, “Nobody,” and hangs up, the light going out in the phone booth.

Pat is reduced to being a vagrant in London—ragged, sitting drunk on a street corner playing his guitar cross-legged. He’s busking, panhandling to make enough money to get home. A passing Londoner stops and offers Pat a twenty-euro note if he’ll play a love song. Pat starts to play the song “Lydia,” but he stops. He can’t do it.

Back in Idaho, with snow on the cabin window marking the passage of time, Lydia gets another phone call. Her stepfather has died in the nursing home. She thanks the caller and goes back to making tea for Pat’s mother, but she can’t. She just stares at her hands. She seems entirely alone in the scene, in the world. And that’s when a knock comes at the door. She answers. It is Pat Bender, framed in the same doorway Lydia stood in at the beginning of the play. Lydia stares at her long-lost boyfriend, this derelict Odysseus who’s been wandering the world trying to get home. It’s the first time they’ve been onstage together since that awful moment when he stood before her, naked, at the start of the play. Another long silence between them follows, echoing the first, extends as long as an audience can possibly bear (Somebody say something!), until Pat Bender gives just the slightest shudder onstage, and whispers, “Am I too late?”—somehow conveying even more nakedness than in the first scene.

Lydia shakes her head no: his mother is alive still. Pat’s shoulders slump, in relief and exhaustion and humility, and he holds out his hands—an act of surrender. Dee’s voice comes again from offstage: “Who is it, dear?” Lydia glances over her shoulder and somehow the moment stretches even longer. “Nobody,” Pat replies, his voice a broken husk. Then Lydia reaches out for his hand, and in the instant their hands touch, the lights go down. The play is over.

Claire gasps, releasing what feels like ninety minutes of air. All the travelers feel it—some kind of completion—and in the rush of applause they feel, too, the explorer’s serendipity: the accidental, cathartic discovery of oneself. In the midst of this release, Michael leans over to Claire and whispers again, “Did you see that?”

On her other side, Pasquale Tursi holds his hand to his heart as if suffering an attack. “Bravo,” he says, and then, “È troppo tardi?” Claire has to guess at his meaning, for their erstwhile Italian translator seems unreachable, his head in his hands. “Fuck me,” Shane says. “I think I’ve wasted my whole life.”

Claire, too, finds herself drawn inward by what she’s just seen. Earlier, she told Shane that her relationship with Daryl was “hopeless.” Now she realizes that throughout the play she was thinking of Daryl, hopeless, irredeemable Daryl, the boyfriend she can’t seem to let go of. Maybe all love is hopeless. Maybe Michael Deane’s rule is wiser than he knows: We want what we want—we love who we love. Claire pulls her phone out and turns it on. She sees the latest text from Daryl: Pls just let me know U R OK.

She types back: I’m okay.

Next to her, Michael Deane puts his hand on her arm. “I’m buying it,” he says.

Claire glances up from her phone, thinking for a moment that Michael is talking about Daryl. Then she understands. She wonders if her deal with Fate is still in play. Is Front Man the great movie that will allow her to stay in the business? “You want to buy the play?” she asks.

“I want to buy everything,” Michael Deane says. “The play, his songs—all of it.” He stands up and looks around the little theater. “I’m buying the whole goddamn thing.”

By flashing her business card (Hollywood? No shit?) Claire gets an enthusiastic invitation to the after-party from a goateed and liberally pierced doorman named Keith. On his directions, they walk a block from the theater toward a brick storefront, which opens to a wide set of stairs, the building intentionally unfinished, all exposed pipes and half-exposed brick. It reminds Claire of climbing to countless parties in college. But there’s something off in the scale, in the width of hallways and the heights of ceilings—all the extravagant, wasted space in these old Western towns.

Pasquale pauses at the door. “È qui, lei?” Is she here?

Maybe, says Shane, looking up from his phone. “C’è una festa, per gli attori.” It is a party for the actors. Shane returns to his phone and sends a text message to Saundra: “Can we talk? Please? I realize now what an ass I’ve been.”

Pasquale looks up at the building where Dee might be, removes his hat, smooths his hair, and starts up the stairs. At the top of the landing, Claire helps the winded Michael Deane up the last steps. There are three doors to three apartments on the second floor and they walk to the back of the building, to the only open door, propped open with a jug of wine.

This back apartment is big and lovely in the same primitive way as the rest of the building. It takes a moment for them to adjust to the candlelight—it’s a huge two-story open loft with high ceilings. The room itself is a work of art, or a junk pile—filled with old school lockers, hockey sticks, and newspaper boxes—all of this surrounding a curved staircase made of old timbers, which seems to float in thin air. Upon further inspection, they can see that the staircase is held with three lines of coiled cable.

“This whole apartment is furnished with found art,” says Keith, the theater doorman, who arrives right behind them. He has spiky, thin hair and painful-looking studs in his lips, neck, upper ears, and nose, as well as pirate hoops in his ears. He has acted in TAGNI productions himself, he tells them, but he’s also a poet, painter, and video artist. (That’s all? Claire wonders. Interpretive dancer? Sand sculptor?)

“A video artist?” Michael is intrigued. “And is your camera nearby?”