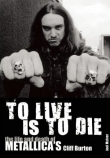

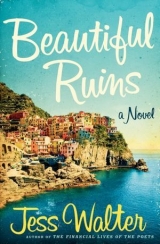

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Shit. Here I’m leaking that the two biggest stars in the biggest picture in the world are together and I’ve got to deal with this? Disaster Deane. If Cleopatra comes out and everyone’s talking about our stars’ torrid affair we got a chance. If they’re talking about Burton knocking up some extra and Liz going back to her husband? We’re dead.

I put together a three-part plan. First: get rid of Burton for a while. I knew Dickie Zanuck was in France filming The Longest Day. And I knew he wanted Burton for a cameo to class up his war picture. I knew Burton wanted to do it. But Skouros hated Dick Zanuck. He’d replaced Zanuck’s old man at Fox and there were people on the Fox board who wanted to replace him with dashing young Dickie. So I went behind Skouros’s back. I called Zanuck and rented him Burton for ten days.

Then I called the doctor and told him to bring this girl D– in for more tests. “What kind of tests?” he said.

“You’re the goddamned doctor! Whatever might get her out of town for a while.”

I was afraid he’d be squirrelly. Hippocratic oath and all that. But this Crane jumped at the chance. Next day he comes up with a big smile. “I told her she had stomach cancer.”

“YOU WHAT?”

Crane explained that the early symptoms of pregnancy were consistent with those of stomach cancer. Cramps and nausea and a bunged-up period.

I’d wanted to get rid of her not kill the poor girl.

Doc said not to worry. He’d told her it was treatable. A Swiss doctor with a new procedure. Then he winked. Of course the doctor in Switzerland puts her under. Gives her the short procedure. And when she wakes up her “cancer” is gone. She’s never the wiser. We send her back to the States to recuperate. And I get her work in some pictures back home. Everyone wins. Problem solved. Movie saved.

But this D– was a wild card. Her mother had died of cancer and she took the phony diagnosis worse than bad. And I underestimated Dick’s feelings for her.

On the other front Eddie Fisher had given up and gone home. I called Dick in France to tell him the good news. Liz was ready to see him again. But he couldn’t see Liz right now. This other girl D– had cancer. She was dying. And Dick wanted to be there for her.

“She’ll be fine. There’s a doctor in Switzerland who—”

Dick interrupted me. This D– didn’t want treatment. She wanted to spend the last of her time with him. And the man was narcissistic enough to think this was a good idea. He’s got a two-day break on The Longest Day and he wants to meet D– on the coast in Italy. And since I was so helpful with him and Liz he wants me to set it up.

What could I do? Burton wants to meet her in this remote little coastal town. Portovenere. Right between Rome and the south of France where he’s shooting The Longest Day. I opened the map and my eye went straight to this flea speck with a similar name. Porto Vergogna. I ask the travel agent to look into it. She says the town is nothing. A cliff-side fishing village. No phones or roads. Can’t even get there by train or car. Only by boat. “Is there a hotel?” I asked. Travel agent said there was a tiny one. So I booked a room in Portovenere for Dick but I sent D– to Porto Vergogna. Told her to wait at the little hotel for Burton. I just needed to stow her for a few days until Dick went back to France and I could get her to Switzerland.

At first it worked. She was stuck in this village. No contact with the world. Burton showed up in Portovenere and found me waiting for him instead. I told him D– had decided to go on to Switzerland for treatment. Don’t worry about her. The Swiss doctors are the best. Then I drove him back to Rome to be with Liz.

But before I could get them back together another problem arrived. Some kid from the hotel where D– is staying shows up in Rome and walks right up and punches me. I’d been in Rome three weeks and I’d gotten used to these Italians gouging me so I gave him some cash and sent him away. But he double-crossed me. Found Burton and told him the whole story. How D– wasn’t dying. How she was pregnant. Then he took Burton back to her. Great. Now Dick is holed up with his pregnant mistress in a hotel in Portovenere. And my movie hangs in the balance.

But did the Deane give up? Not by a long stretch. I called Dickie Zanuck and got Burton back to France for a day of phony reshoots on The Longest Day. And I raced to Portovenere to talk to this D—.

I’ve never seen someone so angry. She wanted to kill me. And I understood why. I did. I apologized. Explained that I had no idea the doctor would say it was cancer. Told her the whole thing had gotten out of hand. Told her that her career was made. Guaranteed. All she had to do was go to Switzerland and she could be in any Fox picture she wanted.

But this was one tough nut. She didn’t want money or acting jobs. I couldn’t believe it. I’d never met a young actor who didn’t want either work or money or both.

This was when I understood the deep responsibility behind my ability to divine desire. It’s one thing to know what people truly want. It’s another to CREATE that want in them. To BUILD that desire.

I pretended to sigh. “Look. This got out of hand. All he wants is for you to get the abortion and stay quiet about it. So you tell me how we can do that.”

She flinched. “What do you mean? ‘All he wants’ ?”

I didn’t blink. “He feels really bad. Obviously. He couldn’t even ask you himself. That’s why he left today. He feels awful about how this all turned out.”

She looked more hurt than when she’d thought she actually had cancer. “Wait. You don’t mean—”

Her eyes closed slowly. It had never occurred to her that Dick might have known all along what I was doing. And frankly it hadn’t occurred to me until that moment either. But in a way it was true.

I acted like I’d assumed she’d known I was acting on his behalf. It was a rush play. I had just a day before Dick got back from France. I had to appear to be defending him. I said he cared deeply for her. That what he was offering didn’t change that. I said she shouldn’t blame him. That his feelings for her were genuine. But he and Liz were under tremendous pressure with this picture—

She interrupted me. She was putting it together. It had been Liz’s doctor who diagnosed her. She covered her mouth. “Liz knows about this, too?”

I sighed and reached out for her hand. But she recoiled like my hand was a snake.

I told her there were no reshoots in France. I said Dick had left a ticket to Switzerland in her name at the La Spezia train station.

She looked like she might vomit. I gave her my business card. She took it. I told her that back in the States we’d go over the slate of upcoming Fox films. She could pick any part she wanted. The next morning I drove her to the train station. She got out with her bags. Her arms slack at her side. She stood and stared at the station and the green hills behind it. And then she began walking. I watched her disappear inside. And I was never surer of anything. She’d go to Switzerland. Then she’d show up in my office in two months. Six at the most. A year. But she’d come to collect. They all do.

But it never happened. She never went to Switzerland. Never came to see me.

That morning Burton arrived back from France to see D– but found me waiting for him instead.

Dick was mad as hell. We went to the train station in La Spezia but the agent said she had only come inside and dropped off her luggage. Then she’d turned around and started walking back toward the hills. Dick and I drove back to Portovenere but she wasn’t there. Dick even made me get a boat to go back to the little fishing town where I’d hid her for a while. But she wasn’t there either. She had disappeared.

We were about to leave the fishing village when the strangest thing happened. This old witch came down from the hills. Cursing and yelling. Our driver translated: “Murderer!” and “I curse you to death.”

I looked over at Burton. That old witch really gave it to him. Years later I’d think about that witch’s curse as I watched poor Dick Burton drink himself under.

In the boat that day he was visibly spooked. It was the perfect time for my come-to-Jesus talk with him.

“Come on, Dick. What were you going to do? Have a kid with her? Marry that girl?”

“Fuck off, Deane.” I could hear it in his voice. He knew I was right.

“This picture needs you. Liz needs you.”

He just stared at the sea.

Of course I was right. Liz was the one. They were in love like that. I knew. He knew. And I made it all possible.

I HAD done exactly what he wanted me to do. Even if he hadn’t known it yet. This was what people like me did for people like him.

From now on this would be my place in the world. To divine desire and do the things that other people wanted done. The things they didn’t even know they wanted yet. The things they could never do themselves. The things they could never admit to themselves.

Dick stared straight ahead in the boat. Did he and I stay friends? Yep. Go to each other’s weddings? You bet we did. Did the Deane bow his head at the great actor’s funeral? Sure I did. And neither of us ever spoke again about what happened in Italy that spring. Not about the girl. Not about the village. Not about the witch’s curse.

That was that.

Back in Rome Dick and Liz rekindled. Got married. Made movies. Won awards. You know the story. One of the great romances in the world. A romance I built.

And the movie? It came out. And just like I thought we lived on the publicity of those two. People think Cleopatra was a flop. No. That picture broke even. Broke even because of what I did. Without me it loses twenty million. Any jackass can make a hit film. It takes giant balls to defuse a bomb.

This was the Deane’s very first assignment. His very first film. And what does he do? Nothing less than keep an entire studio from going under. Nothing less than burn down the old studio system to build a new one.

And when Dickie Zanuck took over Fox that summer you can bet I was rewarded for it. No more Car Barn for me. No more Publicity. But my true reward wasn’t the production job I got from my pal Zanuck. My true reward wasn’t the fame and money about to come my way. The women and the coke and any table I wanted at any restaurant in town.

My reward was a vision that would define my career:

We want what we want.

And that is how I came to be born a second time. How I came into the world and changed it forever. How in the year 1962 on the coast of Italy I invented celebrity.

[Ed. note: Some story, Michael.

Unfortunately, even if we wanted to use this chapter, Legal has some fundamental issues with it, which our attorneys will address in a separate correspondence.

Editorially, though, there’s one other thing you should know: this chapter does not paint you in a very good light. Admitting you broke up two marriages, and faked a young woman’s illness, and bribed her to get an abortion—all in the first chapter—may not be the best way to introduce you to readers.

And even if the lawyers would let us use this anecdote, it’s terribly incomplete. So much is left hanging. What happened to the young actress? Did she get the abortion? Did she have Burton’s baby? Did she go on acting? Is she someone famous? (That would be cool.) Did you try to make it up to her somehow? Track her down? Get her some great film role? Did you at least learn a lesson or have some regret? Do you see where I’m going?

Look, it’s your life and I’m not trying to put words in your mouth. But this story really needs closure—some idea of what happened to the girl, some sense that you at least tried to do the right thing.]

16

After the Fall

September 1967

Seattle, Washington

A DARK STAGE. The sound of waves. Then appears:

MAGGIE in a rumpled wrap, bottle in her hand, her hair in snags over her face, staggering out to the edge of the pier and standing in the sound of the surf. Now she starts to topple over the edge of the pier, when QUENTIN rushes out of the cottage and takes her in his arms. She slowly turns around and they embrace. Soft jazz is heard from within the cottage.

MAGGIE: You were loved, Quentin; no man was ever loved like you.

QUENTIN: [releasing her] My plane couldn’t take off all day—

MAGGIE: [drunk, but aware] I was going to kill myself just now. Or don’t you believe that either?

“Wait, wait, wait.”

Onstage, Debra Bender’s shoulders slumped as the director rose from the first row, black-rimmed glasses at the end of his nose, pencil behind his ear, script in hand. “Dee, sweetheart, what happened?”

She looked down into the front row. “What’s the matter now, Ron?”

“I thought we agreed you were going to take it further. Make it bigger.”

She made quick eye contact with the other actor onstage, Aaron, who sighed and cleared his throat. “I like the way she’s doing it, Ron.” He put his hands out to Debra: There. That’s all I can do.

But Ron ignored the other actor as he strode to the end of the stage and climbed the stairs. He stalked purposefully between the actors and put his hand in the small of Debra’s back, as if leading her in dancing. “Dee, we’ve only got ten days before we open. I don’t want your performance to get lost because it’s too subtle.”

“Yeah, I don’t think subtlety’s the problem, Ron.” She twisted gently away from his hand. “If Maggie starts out as a lunatic, there’s no place for the scene to go.”

“She’s trying to kill herself, Dee. She is a lunatic.”

“Right, it’s just—”

“She’s a drunk, a pill-popper, a user of men—”

“No, I know, but—”

Ron’s hand worked slowly down her back. The man was nothing if not consistent. “This is a flashback in which we see that Quentin did everything he could do to keep her from killing herself.”

“Yeah—” Debra shot another look over Ron’s shoulder, at Aaron, who was miming masturbation.

Ron stepped even closer, in a cloud of aftershave. “Maggie has sucked the life out of Quentin, Dee. She’s killing both of them—”

Over Ron’s shoulder, Aaron air-humped a pretend partner.

“Uh-huh,” Debra said. “Maybe we could talk in private for a second, Ron.”

His hand pressed even farther down. “I think that’s a great idea.”

They stepped offstage and walked up the aisle, Debra sliding into a wood-backed theater seat. Rather than sitting next to her, Ron wedged in between her and the seat-back in front of her, so that their legs were touching. Christ, did this man secrete Aqua Velva? “What’s the matter, sweetheart?”

What’s the matter? She almost laughed. Where to start? Maybe it was agreeing to be in a play about Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe, directed by the married man she’d stupidly slept with six years ago and then bumped into at a Seattle Rep fund-raiser. Or maybe, now that she thought about it, that was her first mistake, going to an event she should’ve known better than to attend. In her first few years back in Seattle, she had avoided the old theater crowd—not wanting to explain either her child or how her “film career” had died. Then she saw an ad for the fund-raiser in the P-I, and she admitted to herself how much she missed it. She walked into the party feeling that warm glow of familiarity, like walking the halls of your old high school. And then she saw Ron, fondue fork in his hand, like a tiny devil. Ron had flourished in the local theater scene in the years since she’d been gone and she was genuinely glad to see him, but he looked at Debra and then at the older man with her—she introduced them: Ron, this is my husband, Alvis—and he immediately went pale and left the party.

“It just seems like you’re taking this play sort of . . . personally,” Debra said.

“This play is personal,” Ron said seriously. He removed his glasses and chewed on the arm. “All plays are personal, Dee. All art is personal. Otherwise, what’s the point? This is the most personal thing I’ve ever done.”

Ron had called two weeks after the fund-raiser and apologized for leaving; he said he just hadn’t been prepared to see her. He asked what she was doing now. She was a housewife, she said. Her husband owned a Chevrolet dealership in Seattle, and she was at home raising their little boy. Ron asked if she missed acting, and she muttered some inanity about how it was nice to take some time off, but Debra thought to herself, I miss it the way I miss love. I’m half a person without it.

A few weeks later, Ron called to say that the Rep was doing an Arthur Miller play and that he was directing it. Would she be interested in reading for one of the leads? She felt breathless, dizzy, twenty again. But, honestly, she probably would have said no if not for the movie she’d just seen: Dick and Liz’s latest film. The Taming of the Shrew, of all things. It was their fifth movie together, and while Debra hadn’t been able to bring herself to see the earlier ones, last year both Burton and Taylor had been nominated for Oscars for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and she’d started to wonder if she’d been wrong about Dick throwing away his talent. Then she saw an advertisement for The Taming of the Shrew in a magazine—“The world’s most celebrated movie couple . . . in the film they were made for!”—and she got a babysitter, said she had a doctor’s appointment, and went to a matinee without telling Alvis. And, as much as she hated to admit it, the film was marvelous. Dick was wonderful in it, artful and honest, playing drunk Petruchio in the wedding scene as if he were born for the part—which, of course, he was. All of it—Shakespeare, Liz, Dick, Italy—fell on her like an early death, and she mourned the loss of her younger self, of her dreams, and in the movie theater that day she wept. You gave all that up, a voice said. No, she thought, they took it from me. She sat there until the credits were done and the lights came up, and still she sat there, alone.

Two weeks later, Ron called to offer her the play. Debra hung up the phone and found herself weeping again—Pat setting down his Tinker Toys to ask, Whassamatter, Mama? And that night, when Alvis got home from work and they had their predinner martinis, Debra told Alvis about the phone call. He was thrilled for her. He knew how much she missed acting. She played devil’s advocate: What about Pat? Alvis shrugged; they’d hire a sitter. But maybe this wasn’t a good time. Alvis just scoffed. There was one more thing, Debra explained: the director was a man named Ron Frye, and before she’d left for Hollywood—and, eventually, Italy—she’d had a short, stupid affair with him. There was no great passion behind it, she said; she was motivated almost entirely by boredom, or maybe just by his attraction to her. And Ron was married at the time. Ah, Alvis said. But there’s nothing between us, she assured Alvis. That was her younger self, the one who believed that if she simply ignored rules and conventions, like marriage, they would have no power over her. She felt no connection to that younger self.

Strong, secure Alvis shrugged off her history with Ron and told her to go for the part. So she did—and she got it. But once rehearsals started, Debra realized Ron had made a connection between himself and Miller’s protagonist, Quentin. In fact, he saw himself as Arthur Miller, the genius waylaid by a shallow, young, villainous actress—the shallow, young, villainous actress being, of course, her.

In the theater, Dee swung her legs until they were no longer touching his. “Look, Ron, about what happened between us—”

“What happened?” he interrupted. “You make it sound like a car accident.” He put his hand on her leg.

Some memories remain close; you can shut your eyes and find yourself back in them. These are first-person memories—I memories. But there are second-person memories, too, distant you memories, and these are trickier: you watch yourself in disbelief—like the Much Ado wrap party at the old Playhouse in 1961, when you seduced Ron. Even recalling it is like watching a movie; you’re up on-screen doing these awful things and you can’t quite believe it—this other Debra, so flattered by his attention, Ron the pipe-smoking actor who went to school in New York and acted Off-Broadway, and you corner him at the wrap party, ramble on about your stupid ambition (I want to do it all: stage and film), you play it coquettish, then aggressive, then shy again, delivering your lines impeccably ( Just one night), almost as if testing the limits of your powers—

But now, in the empty theater, she moved his hand. “Ron. I’m married now.”

“So when I’m married it’s okay. But your relationships are, what . . . sacred?”

“No. We’re just . . . older now. We should be smarter, right?”

He chewed his lip and stared at a point in the back of the theater. “Dee, I don’t mean this to sound harsh, but . . . a fortysomething-year-old drunk? A used-car dealer? This is the love of your life?”

She flinched. Alvis had picked her up here twice after rehearsal, and both times he’d stopped for a couple of drinks first. She pressed on. “Ron, if you cast me in this play because you think we have some unfinished business, all I can say is: We don’t. That’s over. We slept together, what, twice? You need to get past that if we’re going to do this play together.”

“Get past it? What do you think this play is about, Dee?”

“It’s Debra. I go by Debra now. Not Dee. And the play is not about us, Ron. It’s about Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe.”

He took his glasses off, put them back on, and then ran his hand through his hair. He drew a deep, meaningful breath. Actor tics, treating every moment not only as if it had been written for him but as if it were the pivotal scene in the production of his life. “Did it ever occur to you that maybe this is why you never made it as an actress? Because for the great ones, Dee . . . Debra . . . it is about them! It’s always about them!”

And the funny thing was, he was right. She knew. She had seen the great ones up close and they lived like Cleopatra and Antony, like Katherina and Petruchio, as if the scene ended when they left it, the world stopped when they closed their eyes.

“You don’t even see what you are,” Ron said. “You use people. You play with their lives and treat them like they’re nothing.” The words stung with familiarity and Debra could say nothing back. Then Ron turned and stormed back toward the stage, leaving Debra sitting in the wooden theater seat alone. “That’s it for today!” he yelled.

She called home. The sitter, the neighbor girl, Emma, said that Pat had broken the knob off the television again. She could hear him banging on pots in the kitchen. “Pat, I’m on the phone with your mom.”

The banging got louder.

“Where’s his dad?” Debra asked.

Emma said that Alvis had called from Bender Chevrolet and asked if she could babysit until ten P.M., that he’d made dinner reservations after work and that if Debra called, she was supposed to meet him at Trader Vic’s.

Dee checked her watch. It was almost seven. “What time did he call, Emma?”

“About four.”

Three hours? He could be at least six cocktails in—four if he didn’t go straight to the bar. Even for Alvis, that was some head start. “Thanks, Emma. We’ll be home soon.”

“Uh, Mrs. Bender, last time you guys got home after midnight, and I had school the next day.”

“I know, Emma. I’m sorry. I promise we’ll be home earlier this time.” Debra hung up, put her coat on, and stepped out into the cool Seattle air, a light rain seeming to come off the sidewalk. Ron’s car was still in the parking lot and she hurried to her Corvair, climbed in, and turned the key. Nothing. She tried again. Still nothing.

The first two years of their marriage, Alvis had got her a new Chevy from his dealership every six months. This year, though, she’d said it was unnecessary; she’d just keep the Corvair. And now it had some kind of starter problem: of course. She thought about calling Trader Vic’s, but it was only ten or twelve blocks, almost a straight shot down Fifth. She could take the Monorail. But when she got outside, she decided to walk instead. Alvis would be angry—one thing he hated about Seattle was its “scummy downtown,” a bit of which she’d have to walk through—but she thought a walk might clear her mind after that awful business with Ron.

She walked briskly, her umbrella pointed forward into the stinging mist. As she walked, she imagined all the things she should have said to Ron (Yes, Alvis IS the love of my life). She replayed his cutting words (You use people . . . treat them like they’re nothing). She’d used similar words, on her first date with Alvis, to describe the film business. She’d returned to Seattle to find it a different city, buzzing with promise. It had seemed so small to her before, but maybe she had been shrunk by all that happened in Italy, returning beaten to a city that basked in the glow of the World’s Fair; even her old theater chums enjoyed a new playhouse on the fairgrounds. Dee stayed away from the fair, and from the theater, the way she avoided seeing Cleopatra when it came out (reading and reveling, a little shamefully, in its bad reviews); she moved in with her sister to “lick her wounds,” as Darlene aptly described it. Dee assumed she’d give the baby up for adoption, but Darlene talked her into keeping it. Dee told her family that the baby’s father was an Italian innkeeper, and it was that lie that gave her the idea to name the baby after Pasquale. When Pat was three months old, Debra went back to work at Frederick and Nelson, in the Men’s Grill, and she was filling a customer’s ginger ale when she looked up one day to see a familiar man, tall, thin, and handsome, a slight stoop to his shoulders, a burst of gray at his temples. It took a minute to recognize him—Alvis Bender, Pasquale’s friend. “Dee Moray,” he said.

“Your mustache is gone,” she said, and then, “It’s Debra now. Debra Moore.”

“I’m sorry, Debra,” Alvis said, and sat down at the counter. He told her that his father was looking at buying a car dealership in Seattle and he’d sent Alvis out west to scout it.

It was strange bumping into Alvis in Seattle. Italy now seemed like a kind of interrupted dream for her; to see someone from that time was like déjà vu, like encountering a fictional character on the street. But he was charming and easy to talk to, and she found it a relief to be with someone who knew her whole story. She realized that lying to everyone about what had happened had been like holding her breath for the last year.

They had dinner, drinks. Alvis was funny and she felt comfortable immediately with him. His father’s car dealerships were thriving, and that was nice, too, being with a man who could clearly take care of himself. He kissed her cheek at the door to her apartment.

The next day, Alvis came by the lunch counter again, and said that he needed to admit something: it was no accident that he’d found her. She’d told him about herself in those last days in Italy—they had taken a boat together to La Spezia and he’d accompanied her on the train to the Rome airport—and that she figured she’d go back to Seattle. To do what? Alvis had asked. She’d shrugged and said that she used to work at a big Seattle department store, thought maybe she’d go back. So when his father mentioned that he was looking at a Seattle Chevy dealership, Alvis jumped at the chance to find her.

He’d tried other department stores—the Bon Marché and Rhodes of Seattle—before someone at the perfume counter at Frederick and Nelson said there was a tall, blond girl named Debra who used to be an actress.

“So, you came all the way to Seattle . . . just to find me?”

“We are looking at a dealership here. But, yes, I was hoping to see you.” He looked around the lunch counter. “Do you remember, in Italy, you said you liked my book and I said I was having trouble finishing it? Do you remember what you said—‘Maybe it’s finished. Maybe that’s all there is’ ?”

“Oh, I wasn’t saying—”

“No, no,” he interrupted her. “It’s okay. I hadn’t written anything new in five years anyway. I just kept rewriting the same chapter. But you saying that, it was like giving me permission to admit that it’s all I had to say—that one chapter—and to go on with my life.” He smiled. “I didn’t go back to Italy this year. I think I’m done with all that. I’m ready to do something else.”

Something in the way he said those words—ready to do something else—struck her as intimately familiar; she had said the same thing to herself. “What are you going to do?”

“Well,” he said, “that’s what I wanted to talk to you about. What I would really like to do, more than anything, is . . . go hear some jazz.”

She smiled. “Jazz?”

Yes, he said. The concierge at his hotel had mentioned a club on Cherry Street, at the foot of the hill?

“The Penthouse,” she said.

He tapped his nose charades-style. “That’s the place.”

She laughed. “Are you asking me out, Mr. Bender?”

He gave that sly half-smile. “That depends, Miss Moore, on your answer.”

She took a deep, assessing look at him—question-mark posture, thin features, modish swoop of graying brown hair—and thought: Sure, why not.

There you go, Ron: there’s the love of her life.

Now, a block from Trader Vic’s, she saw Alvis’s Biscayne, parked with one tire partly on the curb. Had he been drinking at work? She looked inside the car, but except for a barely smoked cigarette in the ashtray, there was no evidence that this had been one of his binge days.

She walked into Trader Vic’s, into a burst of warm air and bamboo, tiki and totem, dugout canoe hung from the ceiling. She looked around the thatch-matted room for him, but the tables were packed with chattering couples and big round chairs and she couldn’t see him anywhere. After a minute, the manager, Harry Wong, was at her arm with a mai tai. “I think you need to catch up.” He pointed her to a table in the back and there she saw Alvis, a big wicker chair-back surrounding his head like a Renaissance halo. He was doing what Alvis did best: drinking and talking, lecturing some poor waiter who was doing everything he could to edge away. But Alvis had landed one of his big hands on the waiter’s arm and the poor kid was stuck.