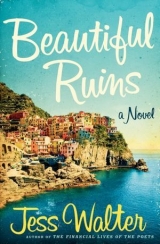

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

3

The Hotel Adequate View

April 1962

Porto Vergogna, Italy

All day he waited for her to come downstairs, but she spent that first afternoon and evening alone in her room on the third floor. And so Pasquale went about his business, which seemed not like business at all but the random behavior of a lunatic. Still, he didn’t know what else to do, so he threw rocks at the breakwater in the cove and he chipped away at his tennis court and he glanced up occasionally at the whitewashed shutters over the windows in her room. In the late afternoon, when the feral cats were sunning themselves on the rocks, a cool spring wind chopped the surface of the sea and Pasquale retreated to the piazza to smoke alone, before the fishermen came to drink. At the Adequate View, there was no noise from upstairs, no sign at all that the beautiful American was even up there, and Pasquale worried again that he had imagined the whole thing—Orenzio’s boat lurching into the cove, the tall, slender American walking up the narrow staircase to the best room in the hotel, on the third floor, pushing open the window shutters, breathing in the salty air, pronouncing it “Lovely,” Pasquale saying she should let him know if there was anything “upon you are happy to having,” and her saying, “Thank you,” and pushing the door closed, leaving him to descend the tight, dark staircase alone.

Pasquale was horrified to find that, for dinner, his aunt Valeria was making her signature ciuppin, a soup of rockfish, tomatoes, white wine, and olive oil. “You expect me to take your rotten fish-head stew to an American cinema star?”

“She can leave if she doesn’t like it,” Valeria said. So, at dusk, with the fishermen pulling their boats up into the cove below, Pasquale clicked up the narrow staircase built into the rock wall. He knocked lightly on the third-floor door.

“Yes?” the American called through the door. He heard the bedsprings creak.

Pasquale cleared his throat. “I am sorry for you disturb. You eat antipasti and a soap, yes?”

“Soap?”

Pasquale felt angry that he hadn’t talked his aunt out of making the ciuppin. “Yes. Is a soap. With fish and vino. A fish soap?”

“Oh, soup. No. No, thank you. I don’t think I can eat anything just yet,” she said, her voice muffled through the door. “I don’t feel well enough.”

“Yes,” he said. “I see.”

He descended the stairs, saying the word soup over and over in his mind. He ate the American’s dinner in his own room on the second floor. The ciuppin was pretty good. He still got his father’s newspapers by mail-boat once a week, and although he didn’t study them the way his father had, Pasquale flipped through them, looking for news about the American production of Cleopatra. But he found nothing.

Later, he heard clumping around in the trattoria and came out, but he knew it wouldn’t be Dee Moray; she did not appear to be a clumper. Instead, both tables were full of local fishermen hoping to get a look at the glorious American, their hats on the tables, dirty hair plastered and combed tight to their skulls. Valeria was serving them soup, but the fishermen were really just waiting to talk to Pasquale, since they’d been out in their boats when the American arrived.

“I hear she is two and a half meters tall,” said Lugo the Promiscuous War Hero, famous for the dubious claim that he had killed at least one soldier from every major participant in the European theater of World War II. “She is a giant.”

“Don’t be stupid,” Pasquale said as he filled their glasses with wine.

“What is the shape of her breasts?” asked Lugo seriously. “Are they round giants or alert peaks?”

“Let me tell you about American women,” said Tomasso the Elder, whose cousin had married an American, making him an expert on American women, along with everything else. “American women cook only one meal a week, but before they marry they perform fellatio. So, as with all life, there is good and there is bad.”

“You should eat from a trough like pigs!” Valeria spat from the kitchen.

“Marry me, Valeria!” Tomasso the Elder called back. “I am too old for sex and my hearing will soon be gone. We are made for each other.”

The fisherman that Pasquale liked best, thoughtful Tomasso the Communist, was chewing on his pipe. He removed it now to weigh in on the subject. He considered himself something of a film buff and was a fan of Italian neorealism and therefore dismissive of American movies, which he blamed for sparking the dreadful commedia all’italiana movement, the antic farces that had replaced the serious existential cinema of the late 1950s. “Listen, Lugo,” he said, “if she is an American actress, it means she wears a corset in cowboy films and has talent only for screaming.”

“Fine. Let’s see those big breasts fill with air when she screams,” Lugo said.

“Maybe she will lie naked on Pasquale’s beach tomorrow,” said Tomasso the Elder, “and we can see for ourselves her giant breasts.”

For three hundred years, the fishermen in town had come from a small pool of young men who’d grown up here, fathers handing over their skiffs and eventually their houses to favored sons, usually the eldest, who married the daughters of other fishermen up and down the coast, sometimes bringing them back to Porto Vergogna. Children moved away, but the villaggio always maintained a kind of equilibrium and the twenty or so houses stayed full. But after the war, when fishing, like everything else, had become an industry, the family fishermen couldn’t compete with the big seiners motoring out of Genoa every week. The restaurants would still buy from a few old fishermen, because tourists liked to see the old men bring in their catches, but this was like working in an amusement park: it wasn’t real fishing, and there was no future in it. An entire generation of Porto Vergogna boys had to leave to find work, to La Spezia and Genoa and even farther for jobs in factories and canneries and in the trades. No longer did the favored son want the fishing boat; already six of the houses were empty, boarded, or brought down; more were sure to follow. In February, Tomasso the Communist’s last daughter, the unfortunately cross-eyed Illena, had married a young teacher and moved away to La Spezia, Tomasso sulking for days afterward. And on one of those cool spring mornings, as Pasquale watched the old fishermen scuff and grumble to their boats, it dawned on him: he was the only person under forty left in the whole town.

Pasquale left the fishermen in the trattoria to go see his mother, who was in one of her dark periods and had refused to leave her bed for two weeks. When he opened the door, he could see her staring at the ceiling, her wiry gray hair stuck to the pillow behind her, arms crossed over her chest, mouth in the placid death face that she liked to rehearse. “You should get up, Mamma. Come out and eat with us.”

“Not today, Pasqo,” she rasped. “Today I hope to die.” She took a deep breath and opened one eye. “Valeria tells me there is an American in the hotel.”

“Yes, Mamma.” He checked her bedsores but his aunt had already powdered them.

“A woman?”

“Yes, Mamma.”

“Then your father’s Americans have finally arrived.” She glanced over at the dark window. “He said they would come and here they are. You should marry this woman and go to America to make a proper tennis field.”

“No, Mamma. You know I wouldn’t—”

“Leave before this place kills you like it killed your father.”

“I would never leave you.”

“Don’t worry about me. I will die soon enough and go to be with your father and with your poor brothers.”

“You’re not dying,” Pasquale said.

“I am already dead inside,” she said. “You should push me out into the sea and drown me like that old sick cat of yours.”

Pasquale straightened. “You said my cat ran away. While I was at university.”

She shot him a glance from the corner of her eye. “It is a saying.”

“No. It’s not a saying. There is no saying such as that. Did you and Papa drown my cat while I was in Florence?”

“I’m sick, Pasqo! Why do you torment me?”

Pasquale went back to his room. That night he heard footsteps on the third floor as the American went to the bathroom, but the next morning she still hadn’t emerged from her room, so he went about his work on the beach. When he returned to the hotel for lunch, his Aunt Valeria said that Dee Moray had come down for an espresso, a piece of torta, and an orange.

“What did she say?” Pasquale asked.

“How would I know? That awful language. Like someone choking on a bone.”

Pasquale crept up the stairs and listened at her door, but Dee Moray was quiet.

He went back outside and down to his beach, but it was hard to tell if the currents had taken any more sand away. He climbed up past the hotel onto the boulders where he’d staked out his tennis court. The sun was high over the coast and hidden by wispy clouds, which flattened the sky and made him feel as if he were under glass. He looked down at the stakes that marked his future tennis court and felt ashamed. Even if he could build forms high enough to contain the concrete to level his court—six feet high at the edges of the boulders—and managed to cantilever some of the court so that it hung out over the cliff, he would still have to blast away at the cliff side with dynamite to flatten the northeast corner. He wondered if it was possible to have a smaller tennis court. Maybe with smaller rackets?

He had just lit a cigarette to think about it when he saw Orenzio’s mahogany boat round the point up the coast near Vernazza. He watched it angle away from the chop along the shoreline, and he held his breath as it passed Riomaggiore. As it got closer he could see there were two people besides Orenzio in the boat. Were these more Americans coming to his hotel? It was almost too much to hope for. Of course, the boat was likely going past him, to lovely Portovenere, or around the point into La Spezia. But then the boat slowed and curled into his narrow cove.

Pasquale began climbing down from his tennis court, hopping from boulder to boulder. Finally, he walked along the narrow trail down to the shoreline, slowing up when he saw that it wasn’t tourists in the boat with Orenzio, but two men: Gualfredo the bastard hotelier, and a huge man Pasquale had never seen before. Orenzio tied the boat up and Gualfredo and the big man climbed out.

Gualfredo was all jowls, bald, with a huge brush mustache. The other man, the giant, appeared to be carved from granite. In the boat, Orenzio looked down, as if he couldn’t bear to meet Pasquale’s eyes.

As Pasquale approached, Gualfredo put his hands out. “So it’s true. Carlo Tursi’s son returns a man to tend the whore’s crack.”

Pasquale nodded grimly and formally. “Good day, Signor Gualfredo.” He’d never seen the bastard Gualfredo in Porto Vergogna before, but the man’s story was well known on the coast: his mother had carried on a long affair with a wealthy Milan banker, and to buy her silence the man had given her petty-criminal son interest in hotels in Portovenere, Chiavari, and Monterosso al Mare.

Gualfredo smiled. “You have an American actress in your old whorehouse?”

“Yes,” Pasquale said. “We sometimes have American guests.”

Gualfredo frowned, his mustache seeming to weigh down his face and his trunk of a neck. He looked over at Orenzio, who pretended to be checking the boat motor. “I told Orenzio there must be a mistake. This woman was surely meant to be at my hotel in Portovenere. But he claims that she really wanted to come to this . . .” He looked around. “Village.”

“Yes,” Pasquale said, “she prefers the quiet.”

Gualfredo stepped in closer. “This is not some Swiss farmer on holiday, Pasquale. These Americans expect a level of service you can’t provide. Especially the American cinema people. Listen to me: I’ve been doing this a long time. It would be regrettable if you were to give the Levante a bad reputation.”

“We are taking care of her,” Pasquale said.

“Then you won’t mind if I talk to her, to make sure there wasn’t some mistake.”

“You can’t,” Pasquale said, too quickly. “She’s sleeping now.”

Gualfredo looked back at Orenzio in the boat and then returned his dead eyes to Pasquale. “Or perhaps you are keeping me from her because she has been tricked by two old friends who took advantage of a woman’s poor Italian to convince her to come to Porto Vergogna rather than Portovenere, as she intended.”

Orenzio opened his mouth to object but Pasquale beat him to it. “Of course not. Look, you’re welcome to come back later when she is not resting and ask her anything you like, but I won’t let you disturb her now. She’s sick.”

A smile pushed at the ends of Gualfredo’s mustache and he gestured at the giant beside him. “Do you know Signor Pelle, of the tourism guild?”

“No.” Pasquale tried to meet the big man’s eyes but they were tiny pinpoints in the fleshy face. His silver suit coat strained beneath his bulk.

“For a small yearly fee and a reasonable tax, the tourism guild provides benefits for all the legitimate hotels—transportation, advertising, political representation . . .”

“Sicurezza,” added Signor Pelle in a bullfrog voice.

“Ah yes, thank you, Signor Pelle. Security,” said Gualfredo, half of his shrub mustache rising in a smirk. “Protection.”

Pasquale knew better than to ask, Protection from what? Clearly, Signor Pelle provided protection from Signor Pelle.

“My father never said anything about this tax,” Pasquale said, and he got a quick glance of warning from Orenzio. It was something Pasquale was trying to figure out, endemic to doing business in Italy, determining which of the countless shakedowns and corruptions were necessary to pay and which could safely be ignored.

Gualfredo smiled. “Oh, your father paid. A yearly fee and also a small per-night foreign guest fee . . . which we haven’t always collected because, frankly, we didn’t think there were any foreign guests in the whore’s crack.” He shrugged. “Ten percent. It’s nothing. Most hotels pass the tax on to their guests.”

Pasquale cleared his throat. “And if I don’t pay?”

This time, Gualfredo did not smile. Orenzio glanced up at Pasquale, another grim look of warning on his face. Pasquale crossed his arms to keep them from shaking. “If you can provide some documentation of this tax, then I will pay it.”

Gualfredo was quiet for a long moment. Finally, he laughed and looked around. He said to Pelle, “Signor Tursi would like documentation.”

Pelle stepped forward slowly.

“Okay,” Pasquale said, angry with himself for caving so quickly. “I don’t need documentation.” But he wished he’d made the brute Pelle take more than one step. He glanced over his shoulder to make sure the American woman’s shutters were closed and that she hadn’t witnessed his cowardice. “I’ll be back in a moment.”

He started back up the crease toward his hotel, face burning. He could never remember feeling more ashamed. His Aunt Valeria was in the kitchen, watching.

“Zia,” Pasquale said. “Did my father pay this tax to Gualfredo?”

Valeria, who had never liked Pasquale’s father, scoffed. “Of course.”

Pasquale counted the money out in his room and started back for the marina, trying to control his anger. Pelle and Gualfredo were facing the sea when he returned, Orenzio sitting in the boat with his arms crossed.

Pasquale’s hand shook as he handed over the money. Gualfredo slapped Pasquale’s face lightly, as if he were a cute child. “We’ll come back later to talk to her. We can figure out the fees and back taxes then.”

Pasquale’s face reddened again, but he held his tongue. Gualfredo and Pelle climbed in the mahogany boat and Orenzio pushed them off without looking at Pasquale. The boat bobbed in the chop for a moment; then the coughing engine found its voice and the men rumbled back up the coast.

Pasquale sulked on the porch of his hotel. There was a full moon that night and the fishermen were out in their boats, using the extra moonlight to hit the thrashing squall of a spring run. Pasquale leaned out over the wooden railing he’d built, smoking and replaying the ugly business with Gualfredo and the giant Pelle, imagining brave rejoinders (Take your tax and use your snake’s tongue to push it up your big friend’s greasy ass, Gualfredo), when he heard the springs on the door open and close. He glanced over his shoulder, and there she was—the beautiful American. She wore tight black pants and a white sweater. Her hair was down, streaked blond and brown, hanging straight below her shoulders. She was holding something in her hands. Typed pages.

“May I join you?” she asked in English.

“Yes. Is my honor,” Pasquale said. “You feel good, no?”

“Better, thank you. I just needed sleep. May I?” She held out her hand and Pasquale wasn’t sure at first what she meant. Finally, he fumbled in his trousers for his cigarette box. He opened it and she took out a smoke. Pasquale thanked his hands for their steady obedience as he struck a match and held it out.

“Thank you for speaking English,” she said. “My Italian is dreadful.” She leaned against the railing, took a long drag and let the smoke out in a sigh. “Whooooo. I needed that,” she said. She considered the cigarette in her hand. “Strong.”

“They are Spanish,” Pasquale said, and then there was nothing else to say. “I must ask: you choose come here, yes, to Porto Vergogna?” he asked finally. “Not to Portovenere or Portofino?”

“No, this is the place,” she said. “I’m meeting someone here. It was his idea. He’ll be here tomorrow, hopefully. I understand this town is quiet and . . . discreet?”

Pasquale nodded, said, “Oh, yes,” and made a note to try to find the word dus-kreet in his father’s English-Italian dictionary. He hoped it meant romantic.

“Oh. I found this in my room. In the bureau.” She handed Pasquale the neat stack of paper she’d carried down: The Smile of Heaven. It was the first chapter of a novel by the only other American guest who had ever come to the hotel before, the writer Alvis Bender, who every year lugged in his little typewriter and a stack of blank carbon paper for two weeks of drinking and occasional writing. He’d left a carbon of the first chapter for Pasquale and his father to puzzle over.

“Is the pages of a book,” Pasquale said, “by an American, yes? . . . A writer. He come to the hotel. Every year.”

“Do you think he would mind? I didn’t bring anything to read and it looks like all the books you have here are in Italian.”

“Is okay, I think, yes.”

She took the pages, leafed through them, and set them on the railing. For the next few minutes they stood quietly, staring out at the lanterns, whose reflections bobbed together on the sea’s surface like two sets of strung lights.

“It’s beautiful,” she said.

“Mmm,” Pasquale said, but then he remembered Gualfredo saying the woman was not supposed to be here. “Please,” he said, recalling an old phrase book: “I inquire your accommodation?” When she said nothing, he added: “You have satisfaction, yes?”

“I have . . . I’m sorry . . . what?”

He licked his lips to give the phrase another try. “I am try to say—”

She rescued him. “Oh. Satisfaction,” she said. “Accommodations. Yes. It’s all very nice, Mr. Tursi.”

“Please . . . I am, for you, Pasquale.”

She smiled. “Okay. Pasquale. And for you I am Dee.”

“Dee,” Pasquale said, nodding and smiling. It felt forbidden and dizzying just to say her name back to her, and the word escaped from his mouth again. “Dee.” And then he knew he had to think of something else to say or he might just stand there all night saying Dee over and over. “Your room is close from a toilet, yes, Dee?”

“Very convenient,” she said. “Thank you, Pasquale.”

“How long will you stay?”

“I . . . I don’t know. My friend has some things to finish. He’ll arrive hopefully tomorrow, and then we’ll decide. Do you need the room for someone else?”

And even though Alvis Bender should be arriving soon, too, Pasquale said, quickly, “Oh, no. Is no one else. All for you.”

It was quiet. Cool. The water clucked.

“What exactly are they doing out there?” she asked, pointing with her cigarette at the lights dancing on the water. Beyond the breakwater, the fishermen dangled the lanterns over the sides of their skiffs, fooling the fish into feeding at the fake dawn, and then swung their nets through the water at the thrashing school.

“They are fishing,” Pasquale said.

“They fish at night?”

“Sometimes at night. But more in the day.” Pasquale made the mistake of staring into those expansive eyes. He’d never seen a face like this, a face that looked so different from every angle, long and equine from the side, open and delicate from the front. He wondered if this was why she was a film actress, this ability to have more than one face. He realized he was staring and had to clear his throat and turn away.

“And the lights?” she asked.

Pasquale glanced out at the water. Now that she mentioned it, this view really was quite striking, the way the fishing lanterns floated above their reflections in the dark sea. “For . . . is . . .” He searched for the words. “Make fish to . . . They . . . uh . . .” He ran into a wall in his mind and mimed a fish swimming up to the surface with his hand. “Go up.”

“The light attracts the fish to the surface?”

“Yes,” Pasquale said, greatly relieved. “The surface. Yes.”

“Well, it’s lovely,” she said again. From behind them, Pasquale heard a few short words, and then “Shhh” from the window next to the deck, where Pasquale’s mother and his aunt would be huddled in the dark, listening to a conversation that neither of them could understand.

A feral cat, the angry black one with the bad eye, stretched near Dee Moray. It hissed when she reached for it and Dee Moray pulled her hand back. Then she stared at the cigarette in her other hand and laughed at something far away.

Pasquale thought she was laughing at his cigarettes.

“They are expensive,” he said defensively. “Spanish.”

She tossed her hair back. “Oh, no. I’ve been thinking about how people sit around for years waiting for their lives to begin, right? Like a movie. You know what I mean?”

“Yes,” said Pasquale, who had lost the sense of what she was saying after people sit but was so taken by the toss of her liquid blond hair and her confidential tone that he would have agreed to having his own fingernails pulled out and fed to him.

She smiled. “I think so, too. I know I felt that way. For years. It was as if I was a character in a movie and the real action was about to start at any minute. But I think some people wait forever, and only at the end of their lives do they realize that their life has happened while they were waiting for it to start. Do you know what I mean, Pasquale?”

He did know what she meant! It was just how he felt—like someone sitting in the cinema waiting for the film to start. “Yes!” he said.

“Right?” she asked, and she laughed. “And when our lives do begin? I mean, the exciting part, the action? It’s all so fast.” Her eyes ran across his face and he flushed. “Maybe you can’t even believe it . . . maybe you find yourself on the outside looking in, like watching strangers eat in a nice restaurant?”

Now she’d lost him again. “Yes, yes,” he said anyway.

She laughed easily. “I’m so glad you know what I mean. Imagine, for instance, being a small-town actress going out to look for film work and having your first role be in Cleopatra? Could you possibly even believe that?”

“Yes,” Pasquale answered more assuredly, picking out the word Cleopatra.

“Really?” She laughed. “Well, I sure couldn’t.”

Pasquale grimaced. He’d answered incorrectly. “No,” he tried.

“I’m from this small town in Washington.” She gestured around with the cigarette again. “Not this small, obviously. But small enough that I was a big deal there. It’s embarrassing now. Cheerleader. County Fair Princess.” She laughed at herself. “I moved to Seattle after high school to act. Life seemed inevitable, like rising out of water. All I had to do was hold my breath and rise all the way to the surface. To some kind of fame or happiness or . . . I don’t know . . .” She looked down. “Something.”

But Pasquale was stuck on one word he wasn’t sure he’d heard correctly: princess? He thought Americans didn’t have royalty, but if they did . . . what would that mean to his hotel, to have a princess stay here?

“Everyone was always telling me, ‘Go to Hollywood . . . you should be in pictures.’ I was acting in community theater and they raised money for me to go. Can you beat that?” She took another drag. “Maybe they wanted to get rid of me.” She leaned in, confiding. “I’d had this . . . fling with another actor. He was married. It was stupid.”

She stared off, and then laughed. “I’ve never told anyone this, but I’m two years older than they think I am. The casting guy for Cleopatra? I told him I was twenty. But I’m really twenty-two.” She thumbed through the typed carbon pages of Alvis Bender’s little novel as if the story of her own life were contained in its pages. “I was using a new name anyway, so I thought, Why not pick a new age, too? If you give them your real age, they sit in front of you doing this horrible math, figuring out how long you have left in the business. I couldn’t bear it.” She shrugged and set the book down again. “Do you think that was wrong?”

He had a fifty-fifty chance of getting this one right. “Yes?”

She seemed disappointed at his answer. “Yeah, I suppose you’re right. Something like that always catches up with you. It’s the thing I hate most about myself. My vanity. Maybe that’s why . . .” She didn’t finish the thought. Instead, she took a last drag of her cigarette, dropped the butt to the wooden patio, and ground it with her deck shoe. “You’re very easy to talk to, Pasquale,” she said.

“Yes, I have pleasure talk to you,” he said.

“Me, too. I have pleasure, too.” She eased up off of the railing, wrapped her arms around her shoulders, and looked out at the fishing lights again. With her arms around herself, she grew even taller and thinner. She seemed to be contemplating something. And then she said, quietly, “Did they tell you that I’m sick?”

“Yes. My friend Orenzio, he tell me this.”

“Did he tell you what’s wrong with me?”

“No.”

She touched her belly. “You know the word cancer?”

“Yes.” Unfortunately, he did know this word. Cancro in Italian. He stared at his burning cigarette. “Is fine, no? The doctors. They can . . .”

“I don’t think so,” she answered. “It’s a very bad kind. They say they can, but I think they’re trying to soften the blow for me. I wanted to tell you to explain that I might seem . . . frank. Do you know this word, frank?”

“Sinatra?” Pasquale asked, wondering if this was the man she was waiting for.

She laughed. “No. Well, yes, but it also means . . . direct, honest.”

Honest Sinatra.

“When I found out how bad it was . . . I decided that from now on I was just going to say what I think, that I would stop worrying about being polite or imagining what people thought of me. That’s a big deal for an actress, refusing to live in the eyes of others. It’s nearly impossible. But it’s important that I don’t waste any more time saying what I don’t mean. I hope that’s okay with you.”

“Yes,” Pasquale said, quietly, relieved to see from her reaction that it was the right answer again.

“Good. Then we’ll make a deal, you and me. We’ll do and say exactly what we mean. And to hell with what anyone thinks about it. If we want to smoke, we’ll smoke, if we want to swear, we’ll swear. How does that sound?”

“I like very much,” Pasquale said.

“Good.” Then she leaned down and kissed him on the cheek, and when her lips grazed his stubbly cheek he felt his breath come short and sharp and he found that he was shaking exactly as when Gualfredo had threatened him.

“Good night, Pasquale,” she said. She grabbed the lost pages of Alvis Bender’s novel and started back for the door, but paused to consider the sign: THE HOTEL ADEQUATE VIEW. “How ever did you come up with the name of the hotel?”

Still stricken by that kiss, unsure how to explain the name, Pasquale simply pointed to the manuscript in her hand. “Him.”

She nodded and looked around again at the tiny village, at the rocks and cliffs around them. “Can I ask, Pasquale . . . what it’s like, living here?”

And this time he had no hesitation in coming up with the proper English word. “Lonely,” Pasquale said.

Pasquale’s father, Carlo, came from a long line of restaurateurs in Florence, and he had always assumed that his sons would follow him in the business. But his oldest, the dashing, jet-haired Roberto, dreamed of being a flier, and in the run-up to World War II he had dashed off to join the regia aeronautica. Roberto did indeed get to fly—three times before his rickety Saetta fighter stalled over North Africa and he fell from the sky like a shot bird. Vowing revenge, the Tursis’ other son, Guido, volunteered for the infantry, sending Carlo into a despairing rage: “If you truly want vengeance, forget the British and go kill the mechanic who let your brother fly that rusty bucket of shit.” But Guido was insistent, and he trucked off with the rest of the Eighth Army’s elite expeditionary force, sent by Mussolini as proof that Italy would do its part to help the Nazis invade Russia. (Bunnies off to eat a black bear, Carlo said.)

It was while comforting his wife over Roberto’s death that the forty-one-year-old Carlo had somehow mustered one last, good seed and passed it on to the thirty-nine-year-old Antonia. At first she disbelieved her condition, then assumed it was temporary (she’d been plagued by miscarriages after her first two). Then, as her belly ballooned, Antonia saw her wartime pregnancy as a sure sign from God that Guido would survive. She named her blue-eyed bambino miracolo Pasquale, Italian for Passover, to honor this deal with God—that the plague of violence sweeping the world would pass over the rest of her family.

But Guido died, too, shot through the throat in the icy meat-fields outside Stalingrad in the winter of ’42. His parents, now ruined by grief, wanted only to hide from the world, and to protect their miracle boy from such insanity. So Carlo sold his stake in the family business to some cousins and bought the tiny Pensione di San Pietro in the most remote place he could find, Porto Vergogna. And there they hid from the world.