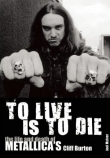

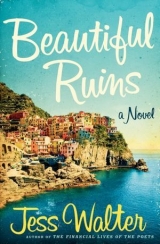

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“Would you rather have one of the other girls?” the prostitute asked. “I’ll go get her, but you still have to pay me.”

Alvis took out his wallet, his hands shaking; he pulled out fifty times the price she’d quoted him. He placed the money on the bed. And then he spoke quietly. “I’m sorry I didn’t just walk you home that night.”

She just stared at the money. Then Alvis Bender walked out, feeling as if the last of his life had seeped out in that room. In the front room, the other whores were reading their magazines. They didn’t even look up. Downstairs, he edged past the skinny, grinning bartender, and by the time he burst outside into the sun Alvis felt crazy with thirst. He hurried across the street, toward another bar, thinking, These bars, thank God, they go on forever. It was a relief, that he would never exhaust all the bars in the world. He could come to Italy once a year to work on this book, and even if it took him the rest of his life to finish it and drink himself to death, that was okay. He knew now what his book would be: an artifact, incomplete and misshapen, a shard of some larger meaning. And if his time with Maria was ultimately pointless—a random encounter, a fleeting moment, perhaps even the wrong whore—then so be it.

In the street, a truck veered around him and he was jolted out of his thoughts long enough to look back over his shoulder, up at the brothel he had just left. There, in the second-story window, stood Maria—at least that’s what he would tell himself—leaning against the glass, watching him, her robe open a little, her fingers stroking the place between her breasts where he had once pressed his face and sobbed. She stared at him a second longer, and then she backed away from the window and was gone.

After that burst of prolific writing, Alvis Bender never made much more progress on his novel when he came to Italy. Instead, he’d cat around Rome or Milan or Venice for a week or two, drinking and chasing women, then come and spend a few days in the quiet of Porto Vergogna. He’d rework that first chapter, rewrite it, reorder things, take a word or two out, put a new sentence in—but nothing came of his book. And yet it always restored him in some way, reading and gently reworking his one good chapter, and seeing his old friend Carlo Tursi, his wife, Antonia, and their sea-eyed son, Pasquale. But now—to find both Carlo and Antonia dead like this, to find Pasquale a full-grown man . . . Alvis wasn’t sure what to think. He had heard of couples dying in short order like this, the grief just too much for the survivor to bear. But it was hard to get his mind around: a year earlier, Carlo and Antonia had both seemed healthy. And now they were gone?

“When did this happen?” he asked Pasquale.

“My father died last spring, my mother three nights ago,” Pasquale said. “Her funeral mass is tomorrow.”

Alvis kept searching Pasquale’s face. He’d been away at school the last few springs when Alvis had come. He couldn’t believe this was little Pasquale, grown into this . . . this man. Even in his grief, Pasquale had the same strange calm about him that he’d had as a boy, those blue eyes steady in their easy assessment of the world. They sat on the patio in the cool morning, Alvis Bender’s portable typewriter and suitcase at his feet where Pasquale had once sat. “I’m so sorry, Pasquale,” he said. “I can go find a hotel up the coast if you want to be alone.”

Pasquale looked up at him. Even though Alvis’s Italian was usually pretty clear, the words were taking a moment to register for Pasquale, almost as if they had to be translated. “No. I would like you to stay.” He poured them each another glass of wine, and slid Alvis’s glass to him.

“Grazie,” Alvis said.

They drank their glasses of wine quietly, Pasquale staring at the table.

“It’s fairly common, couples passing one after the other that way,” said Alvis, whose knowledge sometimes seemed to Pasquale suspiciously broad. “To die of . . .” He tried to think of the Italian word for grief. “Dolore.”

“No.” Pasquale looked up slowly again. “My aunt killed her.”

Alvis wasn’t certain he’d heard right. “Your aunt?”

“Yes.”

“Why would she do that, Pasquale?” Alvis asked.

Pasquale rubbed his face. “She wanted me to go marry the American actress.”

Alvis thought Pasquale might be insane with grief. “What actress?”

Pasquale sleepily handed over the photo of Dee Moray. Alvis took his reading glasses from his pocket, stared at the photo, then looked up. He said flatly, “Your mother wanted you to marry Elizabeth Taylor?”

“No. The other one,” Pasquale said, switching to English, as if such things could only be believed in that language. “She come to the hotel, three days. She make a mistake to come here.” He shrugged.

In the eight years Alvis Bender had been coming to Porto Vergogna, he’d seen only three other guests at the hotel, certainly no Americans, and certainly no beautiful actresses, no friends of Elizabeth Taylor. “She’s beautiful,” Alvis said. “Pasquale, where is your Aunt Valeria now?”

“I don’t know. She ran into the hills.” Pasquale filled their wineglasses again. He looked up at his old family friend, at his sharp features and thin mustache, fanning himself with his fedora. “Alvis,” Pasquale said, “is it okay if we do not talk?”

“Of course, Pasquale,” Alvis said. They quietly drank their wine. And in the quiet, the waves lapped at the cliffs below and a light, salty mist rose in the air, as both men stared out at the sea.

“She read your book,” Pasquale said after a while.

Alvis cocked his head, wondering if he’d heard right. “What did you say?”

“Dee. The American.” He pointed to the blond woman in the photo. “She read your book. She said it was sad, but also very good. She liked it very much.”

“Really?” Alvis asked in English. Then, “Well, I’ll be damned.” Again, it was quiet except for the sea on the rocks, like someone shuffling cards. “I don’t suppose she said . . . anything else?” Alvis Bender asked after a time, once again in Italian.

Pasquale said he wasn’t sure what Alvis meant.

“Concerning my chapter,” he said. “Did the actress say anything else?”

Pasquale said he couldn’t think of anything if she had.

Alvis finished his wine and said he was going up to his room, Pasquale asking if Alvis wouldn’t mind staying in a second-floor room. The actress had stayed on the third floor, he said, and he hadn’t gotten around to cleaning it. Pasquale felt funny lying, but he simply wasn’t ready for someone else in that room yet, even Alvis.

“Of course,” Alvis said, and he went upstairs to put his things in his room, still smiling at the thought of a beautiful woman reading his book.

And so Pasquale was sitting at the table alone when he heard the high rumble of a larger boat motor and looked up just in time to see a speedboat he didn’t recognize round the breakwater into Porto Vergogna’s tiny cove. The pilot had come too quickly into the cove and the boat rose indignantly and settled in the backsplash of its own chop. There were three men in the boat, and as the boat rumbled up to the pier he could see them clearly: a man in a black cap piloting the boat, and behind him, sitting together in back, the snake Michael Deane and the drunk Richard Burton.

Pasquale made no move to go down to the water. The black-capped pilot tied to the wooden bollard and then Michael Deane and Richard Burton climbed out of the boat, stepped onto the pier, and began making their way up the narrow trail to the hotel.

Richard Burton seemed to have sobered up, and was impeccably dressed in a wool suit coat, cuffs of his shirtsleeves peeking out, no tie.

“There’s my old friend,” Richard Burton called to Pasquale as he climbed toward the village. “I don’t suppose Dee’s returned here, sport?”

Michael Deane was a few steps behind Burton, taking measure of the place.

Pasquale looked behind him, at the sad cluster of his father’s village, trying to see it through the American’s eyes. The small block-and-stucco houses must look as exhausted as he felt—as if, after three hundred years, they might yet lose their grip on the cliffs and tumble into the sea.

“No,” Pasquale said. He remained seated, but as both men reached the patio, Pasquale glared up at Michael Deane, who took a half step back.

“So . . . you haven’t seen Dee?” Michael Deane asked.

“No,” Pasquale said again.

“See, I told you,” Michael Deane said to Richard Burton. “Now let’s go to Rome. She’ll turn up there. Or maybe she’ll go on to Switzerland after all.”

Richard Burton ran his hand through his hair, turned, and pointed to the wine bottle on the patio table. “Do you mind terribly, sport?”

Behind him, Michael Deane flinched, but Richard Burton grabbed the bottle, shook it, and showed Deane that it was empty. “Outrageous fortune,” he said, and rubbed his mouth as if he were dying of thirst.

“Inside is more wine,” Pasquale said, “in the kitchen.”

“Bloody decent of you, Pat,” Richard Burton said, patting Pasquale on the shoulder and walking past him into the hotel.

When he was gone, Michael Deane shuffled his feet and cleared his throat. “Dick thought she might have come back here.”

“You lose her?” Pasquale asked.

“I suppose that’s one way to put it.” Michael Deane frowned, as if considering whether or not to say any more. “She was supposed to go on to Switzerland, but it looks like she never got on the train.” Michael Deane rubbed his temple. “If she does come back here, could you contact me?”

Pasquale said nothing.

“Look,” Michael Deane said. “This is all very complicated. You only see this one girl and I’ll admit: it’s been rough business for her. But there are other people involved, other responsibilities and considerations. Marriages, careers . . . it’s not simple.”

Pasquale flinched, recalling when he’d said the same thing to Dee Moray about his relationship with Amedea: It’s not simple.

Michael Deane cleared his throat. “I didn’t come here to explain myself. I came here so you could pass on a message if you see her. Tell her I know she’s angry. But I also know exactly what she wants. You tell her that. Michael Deane knows what you want. And I’m the man who can help her get it.” He reached into his jacket and produced another envelope, which he extended to Pasquale. “There’s an Italian phrase I’ve grown fond of in the last few weeks: con molta discrezione.”

With much discretion. Pasquale waved the money off like it was a hornet.

Michael Deane set the envelope on the table. “Just tell her to contact me if she comes back here, capisce?”

Richard Burton appeared in the doorway then. “Where’d you say that wine was, cap’n?”

Pasquale told him where to find the wine and Richard Burton went back inside.

Michael Deane smiled. “Sometimes the good ones are . . . difficult.”

“And he is a good one?” Pasquale asked without looking up.

“Best I’ve ever seen.”

As if on cue, Richard Burton emerged with the unlabeled wine bottle. “Right, then. Pay the man for the vino, Deane-o.”

Michael Deane put more money on the table, twice the cost of the bottle.

Drawn by the voices, Alvis Bender came out of the hotel, but stopped suddenly in the doorway, staring dumbfounded as Richard Burton toasted him with the dark wine bottle. “Cin cin, amico,” Richard Burton said, as if Alvis were another Italian. He took a long pull from the bottle and turned to Michael Deane again. “Well, Deaner . . . I suppose we’ve worlds to conquer.” He bowed to Pasquale. “Conductor, you’ve a lovely orchestra here. Don’t change a thing.” And with that, he began making his way back to the boat.

Michael Deane reached into his breast pocket and pulled out a business card and a pen. “And this . . .”—with some fanfare, he signed the back of the card and put it on the table in front of Pasquale, as if he were doing a magic trick—“ . . . is for you, Mr. Tursi. Maybe someday I can do something for you, too. Con molta discrezione,” he said again. Then Michael Deane nodded solemnly and turned to follow Richard Burton down the stairs.

Pasquale picked up the signed business card, flipped it over. It read: Michael Deane, Publicity, 20th Century Fox.

In the doorway of the hotel, Alvis Bender stood stock-still, staring open-mouthed as the men made their way down toward the shore. “Pasquale?” he said finally. “Was that Richard Burton?”

“Yes,” Pasquale sighed. And that might have been the end of the whole episode with the American cinema people had not Pasquale’s Aunt Valeria chosen that very moment to reappear, staggering from behind the abandoned chapel like an apparition, mad with grief and guilt and a night spent outside, her eyes vacant, gray hair bursting from her head like blown wire, clothes dirty, her hunger-hollowed face streaked with muddy tears. “Diavolo!”

She walked past the hotel, past Alvis Bender, past her nephew, down toward the two men retreating to the water. The feral cats scattered before her. Richard Burton was too far ahead, but she hobbled down the trail toward Michael Deane, yelling at him in Italian. Devil, killer, assassin: “Omicida!” she hissed. “Assassino cruento!”

Nearly to the boat with his bottle, Richard Burton turned back. “I told you to pay for the wine, Deane!”

Michael Deane stopped and turned, put his hands up to pitch his usual charm, but the old witch kept coming. She raised a knobby finger, pointed it at him, and affixed him with an accusing lamentation, a horrible curse that echoed against the cliff walls: “Io ti maledico a morire lentamente, tormentato dalla tua anima miserabile!”

I curse you to a slow death, tormented by your miserable soul.

“Goddamn it, Deane,” yelled Richard Burton. “Would you get in the boat?”

15

The Rejected First Chapter of Michael Deane’s Memoir

2006

Los Angeles, California

ACTION.

Now where to start? Birth the man says.

Fine. I was birthed fourth of six to the bride of a savvy lawyer in the city of angels in the year 1939. But I was not truly BORN until the spring of 1962.

When I discovered what I was meant to do.

Before that life was what it must be for regular people. Family dinners and swimming lessons. Tennis. Summers with cousins in Florida. Fumbles with easy girls behind the school-house and movie theater.

Was I the brightest? No. Best-looking? Not that either. I was what they called Trouble. Capital T. Envious boys routinely took swings. Girls slapped. Schools spit me out like a bad oyster.

To my father I was The Traitor. To his name and his plans for me: Study abroad. Law school. Practice at HIS firm. Follow HIS footsteps. HIS life. Instead I lived mine. Pomona College for two years. Studied broads. Dropped out in 1960 to be in pictures. A bad complexion shot pocks in my plans. So I decided to learn the biz from inside. Starting at the bottom. A job in publicity at 20th Century Fox.

We worked in the old Fox Car Barn next to the greasy Teamsters. Talked on the phone all day to reporters and gossip columnists. We tried to get good stories in the papers and keep bad ones out. At night I went to openings and parties and benefits. Did I love it? Who wouldn’t? A different lady on my arm every night. The sun and the strip and the sex? Life was electric.

My boss was a fat jug-eared Midwesterner named Dooley. He kept me close because I was fresh. Because I threatened him. But one morning Dooley wasn’t in the office. A frantic call came in. Some sharp was at the studio gate with some interesting photos. A well-known cowboy actor at a party. One of our rising stars. What wasn’t so well-known was that this fellow was also a first-class puff. And these pictures showed him blowing reveille on another fella’s bugle. Most animated performance this particular actor ever gave.

Dooley would be in the next day. But this couldn’t wait. First I reached out to a gossip columnist who owed me. Planted the rumor that the cowboy actor was engaged to a young actress. A rising B-girl. How did I know she’d go for it? She was a girl I’d beefed a few times myself. Having her name connected to a bigger star was the fastest way to the front of the skinnys. Sure she went for it. In this town everything flows upstream. Then I strolled to the gate and casually hired the photographer to shoot promo stills for the studio. Burned the negs of the cowboy-hummer myself.

I got the call at noon. Had it taken care of by five. But next day Dooley was furious. Why? Because Skouros had called. And the head of the studio wanted to see ME. Not him.

Dooley prepped me for an hour. Don’t look old Skouros in the eye. Don’t use profanity. And whatever you do NEVER disagree with the man.

Fine. I waited outside Skouros’s office an hour. Then I stepped inside. He was perched on the corner of his desk. Wore a funeral director’s suit. A thick man with black glasses and slick hair. He gestured to a chair. Offered me a Coca-Cola. “Thank you.” The tight Greek bastard opened the bottle. He poured a third of it into a glass and handed me the glass. He held the rest of that Coke like I hadn’t earned it yet. He sat there on the corner of that desk and watched me drink my tiny Coke while he asked me questions. Where was I from? What did I hope to do? What was my favorite picture? He never even mentioned the cowboy star. And what does this big studio boss want from the Deane?

“Michael. Tell me. What do you know about Cleopatra?”

Stupid question. Every last person in town knew every last thing about that film. Mostly how it was eating Fox alive. How the idea had kicked around for twenty years before Walter Wanger developed it in ’58. But then Wanger caught his wife blowing her agent and he shot the agent in the balls. So Rouben Mamoulian took over Cleo. Budgeted the thing for $2 million with Joan Collins. Who made as much sense as Don Knotts. So the studio dumped her and went after Liz Taylor. The biggest star in the world but she was reeling from bad publicity after she stole Eddie Fisher from Debbie Reynolds. Not even thirty and already on her fourth marriage. At this precarious stage of her career and what’s she do? Demands a million bucks and 10 percent of Cleopatra. No one had ever made half-a-mil on a picture and this dame wants a mil?

But the studio was desperate. Skouros said yes.

Mamoulian took forty people to England to start production on Cleo in 1960. It was hell right off. Bad weather. Bad luck. Sets built. Sets torn down. Sets rebuilt. Mamoulian couldn’t shoot a single frame. Liz got sick. A cold became an abscessed tooth became a brain infection became a staph infection became pneumonia. Woman had a tracheotomy and nearly died on the table. Cast and crew sat around drinking and playing cribbage. After sixteen months of production and seven million bucks he had less than six feet of usable film. A year and a half and the man hadn’t even shot his height in film. Skouros had no choice. He fired Mamoulian. Brought in Joe Mankiewicz. Mankie moved the whole thing to Italy and dumped the whole cast except Liz. Brought in Dick Burton to be Marc Antony. Hired fifty screenwriters to fix the script. Soon it was five hundred pages. Nine hours of story. The studio was losing seventy grand a day while a thousand extras sat around getting paid for nothing and it rained and rained and people walked off with cameras and Liz drank and Mankie started talking about making it into three pictures. The studio was in so deep by now there was no turning back. Not after two years of production and twenty million already down the shitter and God knows how much more while poor tight Skouros rode that goddamn thing all the way down hoping against hope that what showed up on-screen was the greatest goddamned movie . . . spectacle . . . ever . . . made.

“What do I know about Cleopatra?” I looked up at Skouros perched on his desk holding the rest of my cola. “Guess I know a little.”

Right answer. Skouros poured some more Coke in my glass. Then he reached over to his desk. Grabbed a manila envelope. Handed it to me. I will never forget the photo I pulled out of that envelope. It was a work of art. Two people in tight clench. And not any two people. Dick Burton and Liz Taylor. Not Antony and Cleopatra in a publicity shot. Liz and Dick lip-locked on a patio at the Grand Hotel in Rome. Tongues spelunking each other’s mouths.

This was disaster. They were both married. The studio was still dealing with the shit publicity from Liz breaking up the marriage of Debbie and Eddie. Now Liz is getting beefed by the greatest stage actor of his generation? And a top-notch cocksman to boot? What about Eddie Fisher’s little kids? And Burton’s family? His poor Welsh rotters with their coal-stained eyes crying about their lost daddy? The pub would kill the movie. Kill the studio. The movie’s budget was already a guillotine hanging over Skouros’s fat Greek head. This would drop the blade.

I stared at the photo.

Skouros did his best to smile and look calm. But his eyes blinked like a metronome. “What do you think, Deane?”

What did Deane think? Not so fast.

There was something else I knew. But I didn’t really know yet. See? The way you know about sex before you really know about it? I had a gift. But I hadn’t figured how to use it. Sometimes I could see through people. Right to their cores. Like an X-ray. Not a human lie detector. A desire detector. It’s what got me in trouble too. A girl tells me no. Why? She’s got a boyfriend. I hear no but I SEE yes. Ten minutes later the boyfriend walks in to find his girlfriend with a mouthful of Deane. See?

It was like that with Skouros. He was saying one thing but I was seeing something else. So. What now, Deane? Your whole career’s in front of you. And Dooley’s advice is still playing in your head. (Don’t look him in the eye. Don’t use profanity. Don’t challenge him.)

He says it again. “So. What do you think?”

Deep breath. “Well. It looks to me like you’re not the only one getting fucked on this picture.”

Skouros stared at me. Then he straightened up from the corner of his desk. He walked around and sat down. From that moment on he spoke to me like a man. No more quarter-Cokes. The old man broke it down. Liz? Impossible to deal with. Emotional. Stubborn. Contrary. But Burton was a pro. And this wasn’t his first piece of primo tail. Our only chance was to reason with him. When he was sober.

Good luck with that. Your first assignment is to go to Rome and convince a SOBER Dick Burton that if he doesn’t lay off Liz Taylor he’s out of the picture. Right. I flew out the next day.

In Rome I saw right away it wouldn’t be easy. This wasn’t some on-set affair. They were in love. Even that old actress-dipper Burton was in deep with this one. First time in his life he isn’t slopping extras and hairdressers too. At the Grand Hotel I laid it out for him. Gave him Skouros’s whole message. Played it stern. Dick just laughed at me. I’d kick him off the film? Not likely.

Thirty-six hours into the biggest assignment of my life and my bluff’s been called. An A-bomb couldn’t keep Dick and Liz apart.

And no wonder. This was the greatest Hollywood romance in history. Not just some set-screw. Love. All those cute couples now with their conjoined names? Pale imitations. Mere children.

Dick and Liz were gods. Pure talent and charisma and like gods they were terrible together. Awful. A gorgeous nightmare. Drunk and narcissistic and cruel to everyone around them. If only the movie had the drama of these two. They’d film a scene as flat as paper and as soon as the cameras cut Burton would make some wry comment and she’d hiss something back and she’d storm off and he’d chase her back to the hotel and the hotel staff would report these ungodly sounds of breaking glass and yelling and balling and you couldn’t tell the fighting from the fucking with those two. Empty booze decanters flying over hotel balconies. Every day a car wreck. A ten-car pileup.

And that’s when it came to me.

I call it the moment of my birth.

Saints call it epiphany.

Billionaires call it brainstorm.

Artists call it muse.

For me it was when I understood what separated me from other people. A thing I’d always been able to see but never entirely understood. Divination of true nature. Of motivation. Of desirous hearts. I saw the whole world in a flash and I recognized it at once:

We want what we want.

Dick wanted Liz. Liz wanted Dick. And we want car wrecks. We say we don’t. But we love them. To look is to love. A thousand people drive past the statue of David. Two hundred look. A thousand people drive past a car wreck. A thousand look.

I suppose it is cliché now. Obvious to the computer gewgaw-counters with their hits and eyeballs and page views. But this was a transformational moment for me. For the town. For the world.

I called Skouros in L.A. “This can’t be fixed.”

The old man was quiet. “Are you telling me I need to send someone else?”

“No.” I was talking to a five-year-old. “I’m saying this . . . can’t . . . be fixed. And you don’t want to fix it.”

He fumed. This wasn’t someone used to getting bad news. “What the fuck are you talking about?”

“How much do you have into this picture?”

“The actual cost of a film isn’t—”

“How much?”

“Fifteen.”

“You have twenty in if you have a dime. Conservatively you’ll spend twenty-five or thirty before it’s done. And how much will you spend on publicity to recoup thirty mil?”

Skouros couldn’t even say the number.

“Commercials and billboards and ads in every magazine in the world. Eight? Let’s say ten. Now you’re up to forty mil. No picture in history has ever made forty. And let’s be clear. This picture’s no good. I’ve had crabs more enjoyable than this picture. This picture gives shit a bad name.”

Was I killing Skouros? You bet I was. Only to save him.

“But what if I could get you twenty million in FREE publicity?”

“That’s not the kind of publicity we want!”

“Maybe it is.” Then I explained what it was like on set. The drinking. Fighting. Sex. When the cameras ran it was death. But with the cameras off? You couldn’t take your eyes off them. Marc Antony and Cleo-fucking-patra? Who gave a shit about those old moldered bones? But Liz and Dick? THIS is our movie. I told Skouros that as long as this thing rages between them the movie’s got a chance.

Put this fire out? Hell no. What we need to do is stoke it.

It’s easy to see now. In this world of fall and redemption and fall again. Of comeback after comeback. Of carefully released home sex tapes. But no one had thought this way before. Not about movie stars! These were Greek gods. Perfect beings. When one of them fell it was forever. Fatty Arbuckle? Dead. Ava Gardner? Done.

I was suggesting burning the whole town down to save this one house. If I pulled this off people would see our picture not in spite of the scandal but because of it. After this you could never go back. Gods would be dead forever.

I could hear Skouros breathing on the other end of the phone. “Do it.” Then he hung up.

That afternoon I bribed Liz’s driver. When she and Burton came out onto the patio of the villa they’d rented to hide out in camera shutters started popping from balconies in three directions. Photographers I’d tipped. Next day I hired my own shooter to stalk the couple. Made tens of thousands selling those photos. Used that money to bribe more drivers and makeup people for information. I had my own little industry. Liz and Dick were furious. They begged me to find out who was leaking information and I pretended to find out. I fired drivers and extras and caterers and soon Dick and Liz were relying on me to book their remote getaways and still the photographers found them.

And did it work? It broke bigger than any movie story you’ve ever seen. Liz and Dick in every newspaper in the world.

Dick’s wife found out. And Liz’s husband. The story got even bigger. I told Skouros to have patience. To ride it out.

Then poor Eddie Fisher flew to Rome to try to win his wife back and suddenly I had a new problem. For this to work Liz and Dick had to be together when the film wrapped. When the picture opened on Sunset I needed Dick to be boning Liz in the dining room of the Chateau Marmont. And I needed Eddie Fisher to go limping away. But the son of a bitch wanted to fight for his doomed marriage.

The other problem with Liz’s husband being in Rome was Burton. He sulked. Drank. And he went back to this other woman he’d been seeing on the side off and on since his first day in Italy.

She was tall and blond. Uncommon-looking girl. Camera loved her. All the actresses then were either coupes or sedans. Broads or girls-next-door. But this was something else. Something new. She had no film experience. Came from the stage. Mankie inexplicably cast her as Cleopatra’s lady-in-waiting from nothing more than a casting photo. Figured he’d make Liz look more Egyptian by making one of her slaves blond. Little did he know one of Liz’s ladies-in-waiting was actually waiting for Dick.

Christ. I couldn’t believe it when I saw her. Who puts a tall blond woman in a movie set in ancient Egypt?

I’ll call this girl D—.

This D– was what we’d later call a free spirit. One of those moon-eyed easygoing hippie girls I’d get so much joy out of in the sixties and seventies.

Not that I ever beefed this particular one.

Not that I wouldn’t have.

But with Eddie Fisher skulking around Rome Dick went running back to his backup. This D—. I didn’t figure her to be a problem. Girl like that you just throw a bone. A cherry role. A studio contract. And if she won’t play you fire her. What’s that cost? So I had Mankiewicz start giving her five A.M. calls to get her on set. Get her away from Burton. But then she got sick.

We had an American doctor on set. This man Crane. His whole job was to prescribe meds for Liz. He examined this girl D—. Pulled me aside the next day.

“We got a problem. The girl is pregnant. Doesn’t know it yet. Some quack doc told her she can’t have kids. Well she can.”

Of course I’d arranged abortions before. I worked in publicity. It was practically on the business card. But this was Italy. Catholic Italy 1962. At that time it would have been easier to get a moon rock.