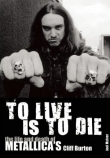

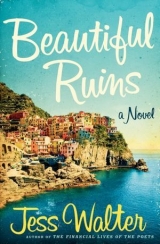

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

9

The Room

Recently

Universal City, California

The Room is everything. When you are in The Room, nothing exists outside. The people hearing your pitch could no more leave The Room than choose to not orgasm. They MUST hear your story. The Room is all there is.

Great fiction tells unknown truths. Great film goes further. Great film improves Truth. After all, what Truth ever made $40 million in its first weekend of wide release? What Truth sold in forty foreign territories in six hours? Who’s lining up to see a sequel to Truth?

If your story improves Truth, you will sell it in The Room. Sell it in The Room and you’ll get The Deal. Get The Deal and the world awaits like a quivering bride in your bed.

–From chapter 14 of The Deane’s Way: How I Pitched Modern Hollywood to America and How You Can Pitch Success Into Your Life Too, by Michael Deane

In The Room, Shane Wheeler feels the exhilaration Michael Deane promised. They are going to make Donner! He knows it. Michael Deane is his Mr. Miyagi and he has just waxed the car. Michael Deane is his Yoda and he has just raised the ship from the muck. Shane did it. He’s never felt so invigorated. He wishes Saundra could’ve been here to see it, or his parents. He might have been a little nervous in the beginning, but he’s never been as sure of anything as he is of this: he killed that pitch.

The Room is suitably quiet. Shane waits. It is old Pasquale who speaks first, pats Shane on the arm, and says, “Penso è andata molto bene.” I think that went very well.

“Grazie, Mr. Tursi.”

Shane glances around the room. Michael Deane is totally inscrutable, but Shane isn’t sure that human expression is even possible anymore on his face. He does look to be deep in thought, though, his wrinkly hands crossed in front of his smooth face, his index fingers raised like a steeple before his lips. Shane looks hard at the man: is one of his brows higher than the other? Or is it just fixed that way?

Then Shane glances to Michael Deane’s right, where Claire Silver has the strangest look on her face. It could be a smile (she loves it!) or a grimace (God, is it possible she hated it?), but if he had to name it he might go with pained bemusement.

Still no one speaks. Shane starts to wonder if maybe he’s misread The Room—all of last year’s self-doubt creeping back in—when . . . a noise comes from Claire Silver. A humming through her nose, like a low motor starting. “Cannibals,” she says, and then she loses it—full, out-of-control, breathless laughter: high, manic, and chirping, and she puts a hand out toward Shane. “I– I’m sorry, it’s not– I just– It’s—” And then she gives in to the laughter; she dissolves in it.

“I’m sorry,” Claire says when she can talk again, “I am. But—” And now the laughter peals again, somehow goes higher. “I wait three years for a good movie pitch . . . and when I get it, what’s it about? A cowboy”—she covers her mouth to try to stop the laughter—“whose family gets eaten by a fat German.” She doubles over.

“He’s not a cowboy,” Shane mumbles, feeling himself shrinking, shriveling, dying. “And we wouldn’t show the cannibalism.”

“No, no, I’m sorry,” Claire says, breathless now. “I’m sorry.” She covers her mouth again and squeezes her eyes shut but she can’t stop laughing.

Shane sneaks a peek at Michael Deane, but the old producer is just staring off, deep in thought, as Claire snorts through her nose—

And Shane feels the last of the air leave his body. He’s two-dimensional now—a flat drawing of his crushed self. This is how he’s felt the last year, during his depression, and he sees now that it was foolish to believe, even for a minute, that he could muster his old ACT confidence—even in its new, humbler form. That Shane is gone now, dead. A veal cutlet. He mutters, “But . . . it’s a good story,” and looks at Michael Deane for help.

Claire knows the rule: no producer ever admits to not liking a pitch, just in case it sells somewhere else and you end up looking like an idiot for passing. You always come up with some other excuse: The market isn’t right for this, or It’s too close to something else we’re doing, or if the idea is truly awful, It just isn’t right for us. But after this day, after the last three years, after everything—she just can’t help herself. All of her gagged responses to three years of ludicrous ideas and moronic pitches gush out in teary, breathless laughter. An effects-driven period thriller about cowboy cannibals? Three hours of sorrow and degradation, all to find out the hero’s son is . . . dessert?

“I’m sorry,” she gasps, but she can’t stop laughing.

I’m sorry: the words seem finally to snap Michael Deane out of some trance. He shoots a cross look at his assistant and drops his hands from his chin. “Claire. Please. That’s enough.” Then he looks at Shane Wheeler and leans forward on his desk. “I love it.”

Claire laughs a few more times, dying sounds. She wipes the tears from her eyes and sees that Michael is serious.

“It’s perfect,” he says. “It’s exactly the kind of film I set out to make when I started in this business.”

Claire falls back in her chair, stunned—hurt, even, beyond the point she realized was possible anymore.

“It’s brilliant,” Michael says, warming up to the idea. “An epic, untold story of American hardship.” And now he turns to Claire. “Let’s option this outright. I want to go to the studio with it.”

He turns back to Shane. “If you’re amenable, we’ll do a short six-month option agreement while I try to set this up with the studio—say, ten thousand dollars? Obviously that’s just to secure the rights against a larger purchase price if it’s further developed. If that’s acceptable, Mr.—”

“Wheeler,” Shane says, barely finding the breath to speak his own name. “Yes,” he manages, “ten thousand is . . . uh . . . acceptable.”

“Well, Mr. Wheeler—that was quite a pitch. You have great energy. Reminds me a bit of myself when I was young.”

Shane looks from Michael Deane to Claire, who has gone pale now, and back again to Michael. “Thank you, Mr. Deane. I practically devoured your book.”

Michael flinches again at the mention of his book. “Well, it shows,” he says, his lips parting to show his gleaming teeth in something like a smile. “Maybe I should have been a teacher, huh, Claire?”

A movie about the Donner Party? Michael as a teacher? Language has completely failed Claire now. She thinks of the deal she’d made with herself—One day, one idea for one film—and realizes that Fate is truly fucking with her now. It’s bad enough trying to live in this vacuous, cynical world, but if Fate is telling her that she doesn’t even understand the rules of the world—well, that’s more than she can bear. People can handle an unjust world; it’s when the world becomes arbitrary and inexplicable that order breaks down.

Michael stands and turns again to his dumbstruck development assistant. “Claire, I need you to set up a meeting at the studio next week—Wallace, Julie . . . everyone.”

“You’re going to take this to the studio?”

“Yes. Monday morning, you, me, Danny, and Mr. Wheeler are going in to pitch The Donner Party.”

“Uh, it’s just called Donner!” Shane offers. “With an exclamation point?”

“Even better,” Michael says. “Mr. Wheeler, can you give that pitch next week? Just like you did today?”

“Sure,” Shane says. “Yeah.”

“Okay then.” Michael pulls out his cell phone. “And Mr. Wheeler, as long as you’re going to be here over the weekend, would it be asking too much for you to help us with Mr. Tursi? We can pay you for translating and put you up at a hotel. Then we’ll set about getting you a film deal on Monday. How does all that sound?”

“Good?” Shane suggests. He glances over at Claire, who looks even more shocked than he is.

Michael opens a drawer in his desk and begins searching for something. “Oh, and Mr. Wheeler, before you go . . . I wonder if you could ask Mr. Tursi one more question.” Michael smiles at Pasquale again. “Ask him . . .” He takes a deep breath and stammers a bit, as if this is the difficult part for him. “I wonder if he knows if Dee . . . what I’m trying to say is . . . was there a child?”

But Pasquale doesn’t need this particular translation. He reaches into an inside pocket of his suit coat and pulls out an envelope. He pulls from it an old, weathered postcard and carefully hands it to Shane. The front of the postcard has a faded blue drawing of a baby. IT’S A BOY! it announces. On the back, the card has been addressed to Pasquale Tursi at the Hotel Adequate View, Porto Vergogna, Italy. Written on the back of the card is a note in careful handwriting:

Dear Pasquale: It seems wrong we didn’t get to say good-bye. But I guess some things are meant just for a certain place and time. Anyway, thank you.

Always—Dee.

P.S.: I named him Pat, after you.

The postcard makes the rounds. When it arrives at Michael, he smiles distantly. “My God. A boy.” He shakes his head. “Well, not a boy anymore, obviously. A man. He’d be . . . Jesus. What? Fortysomething?”

He hands the postcard back to Pasquale, who carefully slides it back in his coat.

Michael stands again and offers his hand to Pasquale. “Mr. Tursi. We’re going to make good on this—you and me.” Pasquale stands and they shake hands uneasily. “Claire, get these gentlemen settled in a hotel. I’ll check in with the private investigator and we’ll reconvene tomorrow.” Michael adjusts his heavy coat over his pajama pants. “Now I’ve got to get home to Mrs. Deane.”

Michael turns to Shane, extends his hand.

“Mr. Wheeler, welcome to Hollywood.”

Michael is already out the door before Claire rises. She tells Shane and Pasquale she’ll be right back, and chases her boss, catching him on the pathway outside the bungalow. “Michael!”

He turns, his face clear and glassy beneath the decorative street-light. “Yes, Claire, what is it?”

She glances back over her shoulder to make sure Shane hasn’t followed her outside. “I can find another translator. You don’t need to string the poor guy along.”

“What are you talking about?”

“The Donner Party?”

“Yes.” He narrows his eyes. “What about it, Claire?”

“The Donner Party?”

He stares at her.

“Michael, are you telling me you liked that pitch?”

“Are you telling me you didn’t?”

Claire blushes. In fact, Shane’s pitch had all the elements: it was compelling, moving, suspenseful. Yeah, it might have even been a great pitch—for a film that could never be made: a Western epic with no gunfights and no romance, a three-hour sobfest that ends with the villain eating the hero’s child.

Claire cocks her head. “So you’re going into the studio Monday morning and pitching a fifty-million-dollar period movie about frontier cannibalism?”

“No,” Michael says, and his lips slide over his teeth again in that facsimile of a smile. “I’m going into the studio Monday morning and pitching an eighty-million-dollar movie about frontier cannibalism.” He turns and starts walking again.

Claire calls after her boss. “And the actress’s kid. It was yours, wasn’t it?”

Michael turns slowly, measuring her. “You have something rare, you know that, Claire? True insight.” He smiles. “Tell me. How did the interview go?”

She’s startled. Just when she starts to see Michael as a kind of caricature, a relic, he’ll show his old power this way.

She glances down at her heels, looks at the skirt she wore today—interview clothes. “They offered me the job. Curator of a film museum.”

“And are you taking it?”

“I haven’t decided.”

He nods. “Look, I really need your help this weekend. Next week, if you still want to leave, I’ll understand. I’ll even help. But this weekend I need you to keep an eye on the Italian and his translator. Get me through this pitch Monday morning and help me find the actress and her kid. Can you do that for me, Claire?”

She nods. “Of course, Michael.” Then, quietly: “So . . . is it? Your kid?”

Michael Deane laughs, looks to the ground and then back up again. “Do you know the old saying, about success having a thousand fathers and failure only one?”

She nods again.

He wraps the coat around himself again. “In that sense, this little fucker . . . might be the only child I ever had.”

10

The UK Tour

August 2008

Edinburgh, Scotland

Some skinny Irish kid knocking into Pat Bender’s shoulder in a Portland bar—that’s what started it.

Pat turned and saw pale, saw gapped front teeth and Superman hair, saw black glasses, Dandy Warhols T-shirt. “Three weeks in America, know what I hate most?” the kid asked. “Your bloody sparts.” He nodded toward the muted Mariners game on the bar TV. “Fact, maybe you can explain something about bess-bowl that I don’t quite get.”

Before Pat could speak, the kid yelled, “Averthing!” and slid into Pat’s booth. “I’m Joe,” he said. “Admit it, Americans suck at every spart you didn’t invent.”

“Actually,” Pat said, “I suck at American sports, too.”

This seemed to amuse and satisfy Joe, and he pointed to Pat’s guitar case, perched next to him in the booth like a bored date. “And do you play that Larrivée?”

“Across the street,” Pat said, “in an hour.”

“Seriously? I’m a bit of a club promoter,” Joe said. “What kind of stuff you play?”

“Failed mostly,” Pat said. “I used to front this band, the Reticents?” No response, and Pat felt pathetic for trying. And how to describe what he did now, which had begun as a talky acoustic set—like that old show Storytellers—but after a year had evolved into a comic-music monologue, Spalding Gray with guitar. “Well,” he told Joe, “I sit on a stool and I sing a little. I tell some funny stories, confess to a lot of bullshit; and, once every few months, after the show, I do some amateur gynecology.”

And that was how it all started—the whole notion of a UK tour. Like every highlight of Pasquale “Pat” Bender’s grubby little career, it wasn’t even his idea. It was this Joe, who sat midway back in a half-full club, laughing at “Showerpalooza,” Pat’s song about the way jam bands stink; howling at Pat’s riff about his band’s stoned liner notes reading like a Chinese food menu; singing along with the crowd at the chorus on “Why Are Drummers So Ducking Fumb?”

There was something magnetic about this Joe. Any other night, Pat would’ve focused on this little stab at a front table, white panties strobe-flashing beneath her skirt, but he kept hearing Joe’s horselaugh, which was bigger than the kid himself, and by the time Pat pivoted into the dark, confessional part of the show—the drugs and breakups—Joe was deeply affected, removing his glasses and dabbing his eyes to the chorus of Pat’s most heartfelt song, “Lydia.”

It’s an old line: you’re too good for me

Yeah, it’s not you it’s me

But Lydia, baby . . . what if that’s the one true thing

You ever got from me—

Afterward, the kid was crazy with praise. He said it was unlike anything he’d ever seen: funny and honest and smart, the music and comic observations complementing each other perfectly. “And that song ‘Lydia’—Jaysus, Pat!”

Just as Pat figured, “Lydia” had made Joe wistful about some girl he’d never gotten over—and he was compelled to tell the whole story, most of which Pat ignored. No matter how much they laughed during the rest of the show, young men were always moved by that song, and its description of the end of a relationship, Pat endlessly surprised at the way they mistook its cold, bitter refutation of romantic negation (Did I ever even exist/Before your brown eyes) for a love song.

Joe started talking right off about Pat performing in London. It was silly talk at midnight, intriguing at one, plausible at two, and by four thirty—smoking Joe’s weed and listening to old Reticents songs in Pat’s apartment in Northeast Portland (“This is fuck-me brilliant, Pat! How’ve I never heard this?”)—the idea had clicked into a plan: a whole range of Pat’s money-girl-career troubles solved by that simple phrase: UK Tour.

Joe said that London and Edinburgh were perfect for Pat’s edgy, smart musical comedy—a circuit of intimate clubs and comedy festivals farmed by eager booking agents and TV scouts. Five A.M. in Portland was one P.M. in Edinburgh, so Joe stepped outside to make a call and came back giddy: an organizer at the Fringe Festival there remembered the Reticents and said there was an opening for a last-minute fill-in. It was all set. Pat just had to get from Oregon to London and Joe would take care of the rest: lodging, food, transportation, six weeks of guaranteed paid gigs, with the potential for more. Hands were shaken, backs clapped, and by morning Pat was contacting his students and canceling lessons for the month. Pat hadn’t felt so excited since his twenties; here he was, heading back out on the road, some twenty-five years after he started. Of course, old fans were sometimes disappointed to see him now—not just that the old front man of the Reticents was doing musical comedy (ignoring Pat’s fine distinction: he was a comic-musical monologist), but that Pat Bender was even alive, that he hadn’t gone the gorgeous-corpse route. Strange how a musician’s very survival made him suspect—as if all the crazy shit of his heyday had been just a pose. Pat had tried writing a song about this strange feeling—“So Sorry to Be Here,” he called it—but the song got bogged down in that junkie braggadocio and he never performed it.

But now he wondered if there hadn’t been a purpose to all that surviving: the second chance to do something . . . BIG. And yet, as excited as he was, even as he typed e-mails to the few friends he could still ask for money (“amazing opportunity” . . . “break I’ve been waiting for”) Pat couldn’t block out a sobering voice: You’re forty-five, running off like some twenty-year-old with a fantasy of getting famous in Europe?

Pat used to imagine such cold-water warnings in the voice of his mother, Dee, who had tried to be an actress in her youth and whose every impulse was to tamp down her son’s ambition with her own disillusionment. Just ask yourself, she’d say when he wanted to join a band or quit a band or kick a guy out of a band or move to New York or leave New York, Is this about the art . . . or is it really about something else?

What a stupid question, he finally said to her. Everything is about something else. The art is about something else! That fucking question is about something else!

But this time it wasn’t his mom’s cautionary voice that Pat heard. It was Lydia—the last time he saw her, a few weeks after their fourth breakup. That day he’d gone to her apartment, apologized yet again, and promised to get sober. For the first time in his life, he told her, he was seeing things clearly; he’d already managed to quit doing almost everything she objected to, and he’d finish the job if that’s what it took to get her back.

Lydia was unlike anyone he’d ever known—smart, funny, self-aware, and shy. Beautiful, too, although she didn’t see it—which was the key to her attraction, that she looked the way she did with no self-consciousness, no embellishment. Other women were like presents he was constantly disappointed in unwrapping, but Lydia was like this secret—so lovely beneath her baggy dresses and low-brimmed Lenin cap. On the last day he saw her, Pat had gently removed that hat. He’d looked into those whiskey-brown eyes: Baby, he said. More than music, booze, anything, it’s you that I need.

That day Lydia stared at him, her eyes wet with regret. She gently took her cap back. Jesus, Pat, she said quietly. Listen to you. You’re like some kind of epiphany addict.

Irish Joe had a buddy in London named Kurtis, a big, bald hip-hop hooligan, and they stayed in the cramped Southwark flat that Kurtis shared with his pale girlfriend, Umi. Pat had never been to London before—had been to Europe only once, in fact, on a high school exchange trip his mom arranged because she wanted him to see Italy. He never made it: a girl in Berlin and a pinch of coke got him sent home early for various violations of tour protocol and human decency. There was always talk of a Japanese tour with the Reticents—so much that it became a band joke, Pat and Benny balking at their one real chance, refusing to open for the “Stone Temple Douchebags.” So this would be the first time Pat performed outside of North America.

“Portland,” said pale Umi upon meeting him, “like the Decemberists.” Pat had experienced the same thing in the nineties when he told New Yorkers he was from Seattle: they’d mutter Nirvana or Pearl Jam, and Pat would grit his teeth and pretend some camaraderie with those ass-smelling latecomer poseur flannel bands. Funny how Portland, Seattle’s goofy little brother, had achieved similar alt-cool coin.

The plan in London was for Pat to open in this basement club, Troupe, where Kurtis worked as a bouncer. Once Pat got to London, though, Joe decided that Edinburgh would be a better place to start, that Pat could refine his show there and use the reviews from the Fringe Festival to build momentum in advance of London. So Pat worked up a shorter, funnier version of the show—a thirty-minute monologue interspersed with six songs. (“Hi, I’m Pat Bender, and if I look familiar it’s because I used to be the singer for one of those bands your pretentious friends talked about to show what obscure musical taste they had. That or we fucked in the bathroom of a club somewhere. Either way, I’m sorry you never heard from me again.”)

He performed the show for Joe and his friends in the flat. He planned to go easy on the darker stuff, and to cut the one serious song, “Lydia,” from this shortened show, but Joe insisted he include it. He said it was the “emotional pivot of the whole bloody thing,” so Pat kept it, and performed it in the flat—Joe once again removing his glasses and wiping his eyes. After the rehearsal, Umi was as enthusiastic as Joe about the show’s prospects. Even quiet, brooding Kurtis admitted it was “quite good.”

The London flat had exposed pipes and old rotting carpet, and for the week they stayed there, Pat never felt at home—certainly not the way Joe did, sitting around all day with Kurtis in their dirty gray boxer briefs, getting high. Joe, it turned out, had been a bit broad in describing himself as a club promoter; he was more of a hanger-on/hash dealer, people occasionally stopping by the flat to buy from him. After a few days with these kids, the twenty-year age difference steepened for Pat: the musical references, the sloppy track suits, the way they slept in and never showered and didn’t seem to notice it was eleven thirty and they were all still in their underwear.

Pat couldn’t sleep more than a few hours at a time, so each morning he cleared out while the others slept. He walked the city, trying to imprint it on his foggy mind—but he was always getting lost on its curving, narrow streets and lanes, with their abruptly changing names, arterials ending in alleys. Pat felt more disoriented each day, not so much by London as by his own inability to absorb it, by his crusty old man’s list of complaints: Why can’t I figure out where I am, or which way to look when crossing a street? Why are the coins so counterintuitive? Are all of the sidewalks this crowded? Why is everything so expensive? Broke, all Pat could do was walk around and look—at free museums, mostly, which gradually overwhelmed him—room after room of paintings at the National Gallery, relics at the British Museum, everything at the Victoria and Albert. He was OD’ing on culture.

Then, on their last day in London, Pat wandered into the Tate Modern, into the vast empty hall, and was floored by the audacity of the art, and the sheer scale of the museum; it was like trying to take in the ocean, or the sky. Maybe it was a lack of sleep, but he felt physically shaken, almost nauseated. Upstairs, he wandered among a collection of surrealist paintings and felt undone by the nervy, opaque genius of their expression: Bacon, Magritte, and especially Picabia, who, according to the gallery notes, had divided the world into two simple categories: failures and unknowns. He was a bug beneath a magnifying glass, the art focused to a blinding hot point on his sleepless skull.

By the time he left the museum, Pat was nearly hyperventilating. Outside was no better. The space-age Millennium Bridge fed like a spoon into the mouth of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London crashing its tones, eras, and genres recklessly, disorienting Pat even more with these massive, fearless juxtapositions: modernist against neoclassic against Tudor against skyscraper.

At the other end of the bridge, Pat came across a little quartet—cello, two violins, electric piano—kids playing Bach over the Thames for change. He sat and listened, trying to catch his breath but awestruck by their casual proficiency, by their simple brilliance. Christ, if street musicians could do that? What was he doing here? He’d always felt insecure about his own musicianship; he could chunk along with anyone on the guitar and be dynamic onstage, but Benny was the real musician. They’d written hundreds of songs together, but standing on the street, listening to these four kids matter-of-factly play the canon, Pat suddenly saw his best songs as ironic trifles, smart-ass commentaries on real music, mere jokes. Jesus, had Pat ever made anything . . . beautiful? The music these kids played was like a centuries-old cathedral; Pat’s lifework had all the lasting power and grace of a trailer. For him, music had always been a pose, a kid’s pissed-off reaction to aesthetic grace; he’d spent his whole life giving beauty the finger. Now he felt empty, shrill—a failure and an unknown. Nothing.

Then Pat did something he hadn’t done in years. Walking back to Kurtis’s flat, he saw a funky music store, a big red storefront called Reckless Records, and after pretending to browse awhile, Pat asked the clerk if they had anything by the Reticents.

“Ah right, yeah,” the clerk said, his pocked face sliding into recognition. “Late eighties, early nineties . . . sort of a soft-pop punk thing—”

“I wouldn’t say soft—”

“Yeah, one of them grunge outfits.”

“No, they were before that—”

“Yeah, we wouldn’t have anything by them,” the clerk said. “We do more—you know—relevant stuff.”

Pat thanked him and left the store.

This was probably why Pat slept with Umi when he got back to the flat. Or maybe it was just her being alone in her underwear, Joe and Kurtis having gone to watch a football match at a pub. “Okay if I sit?” Pat asked, and she swung her legs around on the couch and he stared at the little triangle of her panties, and soon they were fumbling, lurching, as awkward as London traffic (Umi: We mightn’t let Kurty know about this), until they found a rhythm, and eventually, as he’d done so many times before, Pat Bender fucked himself back into existence.

Afterward, with only their legs touching, Umi peppered him with personal questions the way someone might inquire about the fuel economy of a car she’s just test-driven. Pat answered honestly, without being forthcoming. Had he ever been married? No. Not even close? Not really. But what about that song “Lydia”? Wasn’t she the love of his life? It amazed him, what people heard in that song. Love of his life? There was a time when he thought so; he remembered the apartment they’d shared in Alphabet City, barbecuing on the little balcony and doing the crossword puzzle on Sunday mornings. But what had Lydia said after she caught him with another woman? If you really do love me, then it’s even worse, the way you act. It means you’re cruel.

No, Pat told Umi, Lydia wasn’t the love of his life. Just another girl.

They moved backward this way, from intimacy to small talk. Where was he from? Seattle, though he’d lived in New York for a few years and most recently in Portland. Siblings? Nope. Just him and his mother. What about his father? Never really knew the man. Owned a car dealership. Wanted to be a writer. Died when Pat was four.

“I’m sorry. You must be awfully close to your mum, then.”

“Actually, I haven’t talked to her in more than a year.”

“Why?”

And suddenly he was back at that bullshit intervention: Lydia and his mom across the room (We’re worried, Pat and This has to stop), refusing to meet his eyes. Lydia had known Pat’s mom first, had met her through community theater in Seattle, and unlike most of his girlfriends, whose disappointment was all about the way his behavior affected them, Lydia complained on Pat’s mother’s behalf: how he ignored her for months at a time (until he needed money), how he broke promises to her, how he still hadn’t repaid the money he’d taken. You can’t keep doing this, Lydia would say, it’s killing her—her, in Pat’s mind, really meaning both of them. To make them happy, Pat quit everything but booze and pot, and he and Lydia lurched along for another year, until his mother got sick. In hindsight, though, their relationship was probably done at that intervention, the minute she stood on his mother’s side of the room.

“Where is she now?” Umi asked. “Your mum?”

“Idaho,” Pat said wearily, “in this little town called Sandpoint. She runs a theater group there.” Then, surprising himself: “She has cancer.”

“Oh, I’m sorry.” Umi said that her father had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Pat could’ve asked for details, as she’d done, but he said, simply, “That’s tough.”

“Just a bit—” Umi stared at the floor. “My brother keeps saying how brave he is. Dad’s so brave. He’s battling so bravely. Bloody misery, actually.”

“Yeah.” Pat felt squirmy. “Well.” He assumed that enough polite post-orgasm conversation had passed, at least it would have in America; he wasn’t sure of the British exchange rate. “Well, I guess . . .” He stood.

She watched him get dressed. “You do this a bit,” she said, not a question.

“I doubt more than anyone else,” Pat said.

She laughed. “That’s what I love about you good-lookin’ blokes. What, me? Have sex?”

If London was an alien city, Edinburgh was another planet.

They took the train, Joe falling asleep the minute it pulled out of King’s Cross, so that Pat could only guess at the things he saw out the window—clothesline neighborhoods, great ruins in the distance, grain fields and clusters of coastal basalt that made him think of the Columbia River Gorge back home.