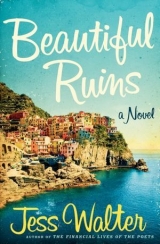

Текст книги "Beautiful Ruins"

Автор книги: Jess Walter

Соавторы: Jess Walter

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Jet tires chirp, grab the runway, and Shane Wheeler jerks awake and checks his watch. Still good. Yeah, his plane’s an hour late, but he’s got three hours until his meeting, and he’s a mere fourteen miles away now. How long can it take to drive fourteen miles? At the gate he uncoils, deplanes, and makes his way in a dream down the long, tiled airport tunnel, through baggage claim and a revolving door, onto a sunlit curb, jumps a bus to the rental-car center, falls in line with the smiling Disney-bounders (who must’ve seen the same $24 online rental-car coupon), and when his turn in line comes, slides his license and credit card to the rental clerk. She says his name with such significance (“Shane Wheeler?”) that for a deluded moment he imagines he’s traveled forward in time and fame, and she’s somehow heard of him—but of course she’s just happy to find his reservation. We live in a world of banal miracles.

“Here for business or pleasure, Mr. Wheeler?”

“Redemption,” Shane says.

“Insurance?”

Coverage declined, upgrade shaken off, pricey GPS and refueling options rejected, Shane heads off with a rental agreement, a set of keys, and a map that looks like it was drawn by a ten-year-old on meth. Ensconced in a rented red Kia, Shane slides the driver’s seat into the same zip code as the steering wheel, takes a breath, starts the car, and rehearses the first words of his first-ever pitch: So there’s this guy . . .

An hour later, he’s somehow farther from his appointment. Shane’s Kia is gridlocked and, he thinks, might even be pointed in the wrong direction (the GPS now seeming like a screaming deal). Shane tosses aside the worthless rental-car map and tries Gene Pergo’s cell: voice mail. He tries the agent who set up the meeting, but the agent’s assistant says, “Sorry, I don’t have Andrew,” whatever that means. He begrudgingly tries his mom’s cell, then his dad’s, and finally, the home number: Shit, where are they? The next number that pops into his head is his ex-wife’s. Saundra is the last person he wants to call right now—but that’s just how desperate he feels.

His name must pop up on her phone still, because her first words are: “Tell me you’re calling because you have the rest of the money you owe me.”

This is what he hoped to avoid—the whole who-ruined-whose-credit and who-stole-whose-car business that has colored their every conversation for a year. He sighs. “As a matter of fact, I’m in the process of getting your money right now, Saundra.”

“You’re not giving plasma again?”

“No. I’m in LA, pitching a movie.”

She laughs and then realizes he’s serious. “Wait. You’re writing a movie now?”

“No. I’m pitching a movie. First you pitch it, then you write it.”

“No wonder movies suck,” she says. This is classic Saundra: a waitress with a poet’s pretensions. They met in Tucson, where she worked at Cup of Heaven, the coffee shop where Shane went to write every morning. He fell for, in order: her legs, her laugh, and the way she idealized writers and was willing to support his work.

For her part—she said at the end—she fell mostly for his bullshit.

“Look,” Shane says, “could you just hold the cultural criticism and MapQuest Universal City for me?”

“You seriously have a meeting in Hollywood?”

“Yes,” Shane says. “With a big producer on a studio lot.”

“What are you wearing?”

He sighs and tells her what Gene Pergo told him, that it doesn’t matter what one wears to a pitch meeting (Unless you own a bullshit-proof suit).

“I’ll bet I know what you’re wearing,” Saundra says, and proceeds to describe his outfit down to the socks.

Shane is regretting this call. “Just help me figure out where I’m going.”

“What’s your movie called?”

Shane sighs. He has to remember they’re no longer married; her bitter-cool ironic streak has no power over him anymore. “Donner!”

Saundra is quiet a moment. But she knows his interests, his reading table obsessions. “You’re writing a movie about cannibals?”

“I told you, I’m pitching a movie, and it’s not about cannibals.”

Clearly, the Donner Party could be a tough subject for a film. But pitches are all in the take, as Michael Deane wrote in the oft-copied chapter fourteen of his memoir/self-help classic, The Deane’s Way:

Ideas are sphincters. Every asshole has one. Your take is what counts. I could walk into Fox today and sell a movie about a restaurant that serves baked monkey balls if I had the right take.

And Shane has the perfect “take.” Donner! will concern itself not with the classic Donner Party story—all those people stuck at the awful camp, freezing and starving to death and finally eating one another—but with the story of a cabinetmaker in the party, named William Eddy, who leads a group of people, mostly young women, on a harrowing, heroic journey out of the mountains to safety, and then—attention, third act!—when he’s regained his strength, returns to rescue his wife and kids! As Shane pitched this idea over the phone to the agent Andrew Dunne, he felt himself becoming animated by its power: It’s a story of triumph, he told the agent, an epic story of resiliency! Courage! Determination! Love! That very afternoon the agent set up a meeting with Claire Silver, a development assistant for . . . get this . . . Michael Deane!

“Huh,” Saundra says when she’s heard the whole story. “And you really think you can sell this thing?”

“Yes. I do,” Shane says, and he does. It’s a key sub-tenet of Shane’s movie-inspired ACT-as-if faith in himself: his generation’s profound belief in secular episodic providence, the idea—honed by decades of entertainment—that after thirty or sixty or one hundred and twenty minutes of complications, things generally work out.

“Okay,” Saundra says—still not entirely immune to the undeniable charm of Shane’s deluded self-belief—and she gives him the MapQuest instructions. When he thanks her, Saundra says, “Good luck today, Shane.”

“Thanks,” Shane says. And, as always, his ex-wife’s passionless, entirely genuine goodwill leaves him feeling like the loneliest person on the planet.

It’s over. What a stupid deal: one day to find a great idea for a film? How many times has Michael told her, We’re not in the film business, we’re in the buzz business. And yes, the day’s not quite over, but her two forty-five is picking at an open scab on his forehead while pitching a TV procedural (So there’s this cop—pick—a zombie cop) and Claire feels the loss of something vital in her, the death of some optimism. Her four P.M. looks like a no-show (somebody named Shawn Weller . . . ) and when Claire checks her watch—four ten—it is through bleary, sleepy eyes. So that’s it. She’s done. She won’t say anything to Michael about her disillusionment; what would be the point? She’ll quietly give two weeks, box up her things, and slink out of this office into a job warehousing souvenirs for the Scientologists.

And what about Daryl? Does she dump him today, too? Can she? She’s tried breaking up with him recently, but it never takes. It’s like cutting soup—nothing to push against. She’ll say, Daryl, we need to talk, and he just smiles in that way of his, and they end up having sex. She even suspects it turns him on a little. She’ll say, I’m not sure this is working, and he’ll start taking off his shirt. She’ll complain about the strip clubs and he’ll just look amused. (Her: Promise me you won’t go again? Him: I promise I won’t make you go.) He doesn’t fight, doesn’t lie, doesn’t care; the man eats, breathes, screws. How do you disengage from someone who’s already so profoundly disengaged?

She met him on what is now looking like the only movie she’ll ever work on—Night Ravagers. Claire has always been weak for ink, and Daryl, who had a walk-on (lurch-on? stagger-on?) as Zombie #14, had these great ropy, tattooed arms. She’d dated mostly smart, sensitive types (who made her smart sensitivity seem redundant) and a couple of slick industry types (whose ambition was like a second dick). She hadn’t yet tried the unemployed-actor type. And wasn’t this what she had in mind when she left the cocoon of film school in the first place, tasting the visceral, the worldly? And at first, visceral-worldly was as good as advertised (she recalls wondering: Was I ever even touched before this?). Thirty-six hours later, as she lay postcoital in bed with the best-looking guy she’s ever slept with (sometimes she just likes to look at him), Daryl matter-of-factly admitted that he’d just been tossed out by his girlfriend and had no place to live. Almost three years later, Night Ravagers remains Daryl’s best acting credit, and Zombie #14 remains a gorgeous lump in her bed.

No, she won’t break up with Daryl. Not today. Not after the Scientologists and the proud grandpas, the lunatics, zombie cops, and skin-pickers. She’ll give Daryl one more chance, go home, bring him a beer, nestle into his broad, tatted shoulder; together they’ll watch the TeeVee (he likes those trucks that drive across the ice on the Discovery Channel) and she’ll have that tenuous connection to life, at least. No, it’s not the stuff of dreams, but it’s a perfectly American thing to do, a whole nation of Night Ravager zombies racing across the horizon, burning through peak oil to get home and sit dull-eyed, watching Ice Road Truckers and Hookbook on the fifty-five-inch flat (the Double Nickel, as Daryl calls it, the Sammy Hagar).

Claire grabs her coat and starts for the door. She pauses, glances back over her shoulder at the office where she thought she might get to make something great—silly Holly Golightly dream—and once more checks her watch: 4:17 and counting. Outside, she locks the door behind her, takes a breath, and goes.

The clock in Shane’s rented Kia also reads 4:17—he’s more than a quarter-hour late, and he’s dying. “Shit shit shit!” He pounds the steering wheel. Even after finally getting turned around, he got caught in several traffic snarls and took the wrong exit. By the time he rolls up to the studio gate and the security guard shrugs and informs him that his destiny is at the other gate, he is twenty-four minutes late, sweating through his carefully chosen whatever-clothing. When he arrives at the proper gate, he’s twenty-eight minutes late—thirty when he finally gets his ID back from the second security guard, shakily slaps a parking pass on his dash, and pulls into the lot.

Shane is only two hundred feet away now from Michael Deane’s bungalow, but he stumbles out of his car the wrong way, wanders among the big soundstages—it is the cleanest warehouse district in the world—and finally walks in a circle, toward a nest of bungalows and a tram filled with fanny-packed tourists on a studio tour, holding up cameras and cell phones, listening to a microphone-aided guide tell apocryphal stories of bygone magic. The camera-people listen breathlessly, waiting for some connection to their own pasts (I loved that show!), and when Shane staggers up to their tram, the star-alert tourists run his disheveled hair, broad sideburns, and thin, frantic features through the thousands of celebrity faces they keep on file—Is that a Sheen? A Baldwin? A celebrity rehabber?—and while they can’t quite match Shane’s oddly appealing features with anyone famous, they take pictures anyway, just in case.

The tour guide chutters into his headset, telling the tram-people in something like English how a certain famous breakup scene from a certain famous television show was famously filmed “right over there,” and as Shane approaches, the driver holds up a finger so he can finish his story. Sweating, near tears, in full overheated self-loathing, fighting every urge to call his parents—his ACT resolve now a distant memory—Shane finds himself staring at the tour guide’s name tag: ANGEL.

“Excuse me?” Shane says.

Angel covers the headset microphone and says, heavily accented, “Fuck jou want?” Angel is roughly his age, so Shane tries for late-twenties camaraderie. “Dude, I’m totally late. Can you help me find Michael Deane’s office?”

Something about this question causes another tourist to take Shane’s picture. But Angel merely jerks his thumb and drives the tram away, revealing a sign that he was blocking, pointing to a bungalow: MICHAEL DEANE PRODUCTIONS.

Shane looks at his watch. Thirty-six minutes late now. Shit shit shit. He runs around the corner and there it is—but blocking the door to the bungalow is an old man with a cane. For a second, Shane thinks it might be Michael Deane himself, even though the agent said Deane wouldn’t be at the meeting, that it would just be his development assistant, Claire Something. Anyway, it’s not Michael Deane. It’s just some old guy, seventy maybe, in a dark gray suit and charcoal fedora, cane draped over his arm, holding a business card. As Shane’s feet clack on the pavement, the old man turns and removes his fedora, revealing a shock of slate hair and eyes that are a strange, coral blue.

Shane clears his throat. “Are you going in? ’Cause I . . . I’m very late.”

The man holds out a business card: ancient, wrinkled and stained, the type faded. It’s from another studio, 20th Century Fox, but the name is right: Michael Deane.

“You’re in the right place,” Shane says. He presents his own Michael Deane business card—the newer model. “See? He’s at this studio now.”

“Yes, I go this one,” says the man, heavily accented, Italian—Shane recognizes it from the year he studied in Florence. He points at the 20th Century Fox card. “They say, go this one.” He points to the bungalow. “But . . . is locked.”

Shane can’t believe it. He steps past the man and tries the door. Yes, locked. Then it’s over.

“Pasquale Tursi,” says the man, holding out his hand.

Shane shakes it. “Big Loser,” he says.

Claire has texted Daryl to ask what he wants for dinner. His answer, kfc, is followed by another text: unrated hookbook—she’s told Daryl that her company is about to stream out an unrated, raunchier version of that show, full of all the nudity and sodden stupidity they couldn’t air on regular TV. Fine, she thinks. She’ll go back for her company’s apocalyptic TV show, then swing through the KFC drive-through, and she’ll curl up with Daryl and deal with her life on Monday. She turns her car around, is waved back through security, and parks back in the lot above Michael’s bungalow office. She starts back to the office to get the raw DVDs, but when she rounds the path, Claire Silver sees, standing at the door to the bungalow, not one Wild Pitch Friday lost cause . . . but two. She stops, imagines turning around and leaving.

Sometimes she makes a guess about Wild Friday Pitchers, and she does this now: mop-haired sideburns in factory-torn blue jeans and faux Western shirt? Michael’s old coke dealer’s son. And old silver-haired, blue-eyed charcoal suit? This one’s tougher. Some guy Michael met in 1965 while getting rimmed at an orgy at Tony Curtis’s house?

The frantic younger guy sees her approaching. “Are you Claire Silver?”

No, she thinks. “Yes,” she says.

“I’m Shane Wheeler, and I am so sorry. There was traffic and I got lost and . . . Is there any chance we could still have our meeting?”

She looks helplessly at the older guy, who removes his hat and extends the business card. “Pasquale Tursi,” he says. “I am look . . . for . . . Mr. Deane.”

Great: two lost causes. A kid who can’t find his way around LA, and a time-traveling Italian. Both men stare at her, hold out Michael Deane business cards. She takes the cards. The young guy’s card is, predictably, newer. She turns it over. Below Michael’s signature is a note from the agent Andrew Dunne. She recently screwed Andrew, not in that she had sex with him—that would be forgivable—but she asked him to hold off circulating a sizzle reel for his client’s unscripted fashion show, If the Shoe Fits, while Michael considered it; instead, he optioned a competing show, Shoe Fetish, which effectively killed Andrew’s client’s idea. The agent’s note reads: “Hope you enjoy!” A payback pitch: Oh, this must be horrible.

The other card is a mystery, the oldest Michael Deane business card she’s ever seen, faded and wrinkled, from Michael’s first studio, 20th Century Fox. It’s the job that catches her—publicity? Michael started in publicity? How old is this card?

Honestly, after the day she’s had, if Daryl had texted anything other than kfc and unrated hookbook, she might just have told these two guys the game was up—they’d missed today’s charity wagon. But she thinks again about Fate and the deal she made. Who knows? Maybe one of these guys . . . right. She unlocks the door and asks their names again. Sloppy sideburns = Shane. Popping eyes = Pasquale.

“Why don’t you both come on back to the conference room,” she says.

In the office, they sit beneath posters for Michael’s classic movies (Mind Blow; The Love Burglar). No time for pleasantries; it’s the first pitch meeting in history in which no water is proffered. “Mr. Tursi, would you like to go first?”

He looks around, confused. “Mr. Deane . . . is not here?” His accent is heavy, as if he’s chewing on each word.

“I’m afraid he’s not here today. Are you an old friend of his?”

“I meet him . . .” He stares at the ceiling. “Eh, nel sessantadue.”

“Nineteen sixty-two,” says the young guy. When Claire looks curiously at him, Shane shrugs. “I spent a year studying in Italy.”

Claire imagines Michael and this old guy, back in the day, tooling around Rome in a convertible, screwing Italian actresses, drinking grappa. Now Pasquale Tursi looks disoriented. “He say . . . you . . . ever need anything.”

“Sure,” Claire says. “I promise I’ll tell Michael all about your pitch. Why don’t you just start at the beginning?”

Pasquale squints as if he doesn’t understand. “My English . . . is long time . . .”

“The beginning,” Shane tells Pasquale. “L’inizio.”

“There’s this guy . . .” Claire urges.

“A woman,” Pasquale Tursi says. “She come to my village, Porto Vergogna . . . in . . .” He looks over at Shane for help.

“Nineteen sixty-two?” Shane says again.

“Yes. She is . . . beautiful. And I am build . . . eh . . . a beach, yes? And tennis?” He rubs his brow, the story already getting away from him. “She is . . . in the cinema?”

“An actress?” Shane Wheeler asks.

“Yes.” Pasquale Tursi nods and stares off into space.

Claire checks her watch and does her best to jumpstart his pitch: “So . . . an actress comes to this town and she falls for this guy who’s building a beach?”

Pasquale looks back at Claire. “No. For me . . . maybe, yes. E– l’attimo, yes?” He looks at Shane for help. “L’attimo che dura per sempre.”

“The moment that lasts forever,” Shane says quietly.

“Yes,” Pasquale says, and nods. “Forever.”

Claire feels pinched by those words in such close proximity, moment and forever. Not exactly KFC and Hookbook. She suddenly feels angry—at her silly ambition and romanticism, at her taste in men, at the loopy Scientologists, at her father for watching that stupid movie and then leaving, at herself for coming back to the office—at herself because she keeps hoping for better. And Michael: Goddamn Michael and his goddamn job and his goddamn business cards and his goddamn old buzzard friends and the goddamn favors he owes the goddamn people he screwed back when he screwed everything that screwed.

Pasquale Tursi sighs. “She was sick.”

Claire flushes with impatience: “With what? Lupus? Psoriasis? Cancer?”

At the word cancer, Pasquale looks up suddenly and mutters in Italian, “Sì. Ma non è così semplice—”

And that’s when the kid Shane interrupts. “Uh, Ms. Silver? I don’t think this guy’s pitching.” And he says to the man, in slow Italian, “Questo è realmente accaduto? Non in un film?”

Pasquale nods. “Sì. Sono qui per trovarla.”

“Yeah, this really happened,” Shane tells Claire. He turns back to Pasquale. “Non l’ha più vista da allora?” Pasquale shakes his head no, and Shane turns back to Claire again. “He hasn’t seen this actress in almost fifty years. He came to find her.”

“Come si chiama?” Shane Wheeler asks.

The Italian looks from Claire to Shane and back again. “Dee Moray,” he says.

And Claire feels a tug in her chest, some deeper shift, a cracking of her hard-earned cynicism, of this anxious tension she’s been fighting. The actress’s name means nothing to her, but the old guy seems utterly changed by saying it aloud, as if he hasn’t said the name in years. Something about the name affects her, too—a crush of romantic recognition, those words, moment and forever—as if she can feel fifty years of longing in that one name, fifty years of an ache that lies dormant in her, too, maybe lies dormant in everyone until it’s cracked open like this—and so weighted is this moment she has to look to the ground or else feel the tears burn her own eyes, and at that moment Claire glances at Shane, and sees that he must feel it, too, the name hanging in the air for just a moment . . . among the three of them . . . and then floating to the floor like a falling leaf, the Italian watching it settle, Claire guessing, hoping, praying the old Italian will say the name once again, more quietly this time—to underline its importance, the way it’s so often done in scripts—but he doesn’t do this. He just stares at the floor, where the name has fallen, and it occurs to Claire Silver that she’s seen too goddamn many movies.