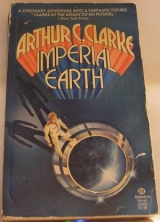

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

“Oh, we are, essentially. I don’t think we’ll ever develop the-ah-‘corridor culture’ you have on the Moon and planets.”

Professor Washington had used that anthropological cliche with some caution. Obviously he was not quite sure if Duncan approved of it. Nor, for that matter, was Duncan himself; but he had to admit that despite all the debates that had raged about it, the phrase was an accurate description of

Titan’s social life.

“One of the chief problems of entertaining off worlders like yourself,” said Washington somewhat ruefully, “is that I find myself explaining at great length things that they know perfectly well, but are too polite

to admit. A coiinle of years ago I took a statistician from Tranquillity along this road, and gave him a brilliant lecture on the population changes here in the Washington-Virginia region over the last three hundred years. I thought he’d be interested, and he was.

If I’d done my homework properly-which I usually do, but for some reason had neglected in this case-I’d have found that he’d written the standard work on the subject. After he’d left, he sent me a copy, with a very nice inscription.”

Duncan wondered how much “homework” George had done on him; doubtless a good deal.

“You can assume my total ignorance in these matters. Still, I should have realized that fusor technology would be almost as important on Earth as off it.“It’s not my field, but you’re probably right. When it was cheaper and simpler to melt a home underground than to build it above—and to fit it with viewscreens that were better than any conceivable window-it’s not surprising that the surface lost many of its attractions. Not all, though.”

He gestured toward the left-hand side of the parkway.

They were approaching a small access road, which merged gently into the main traffic lane. It led into a wood about a kilometer away, and through the trees Duncan could glimpse at least a dozen houses. They were all of different design, yet had common features so that they formed a harmonious group. Every one had steeply gabled red roofs, large windows, gray stone walls-and even chimneys. These were certainly not functional, but many of them served to support complicated structures of metal rods.

“Fake antique,” said Washington with some disapproval.

“Mid-twentieth-century TV antennas. Oh well, there’s no accounting for tastes.”

The road was plunging downhill now, and was about to pass under a graceful bridge car ring a road much wider than the parkway. It was also carrying considerably more traffic, moving at a leisurely twenty or thirty kilometers an hour.

“Enjoying the good weather,” said Washington.

“You only see a few madmen there in the winter. And you may not

believe this, but there was a time when the motor ways were the wide roads. They had to be when there was a hundred times as much traffic and no automatic steering.” He shuddered at the thought. “More people were killed on these roads than ever died in warfare-did you know that? And of course they still get killed, up there on the bikeways. No one’s ever discovered a way to stop cyclists from wobbling; that’s another reason why the road’s so wide.”

As they dived under the bridge, a colorful group of young riders waved down at them, and Washington replied with a cheerful salute.

“When I was thirty years younger,” he said wistfully, “a gang of us set off for California on the Transcontinental Bikeway. No electro cycles allowed, either. Well, we were unlucky-ran into terrible weather in Kansas. Some of us made it, but I wasn’t one of them. I’ve still got a twelve-speed Diamond

Special-all carbon fiber and beryllium; you can lift it with one finger.

Even now, I could do a hundred klicks on it, if I were fool enough to try.”

The big car was slowing down, its computer brain sensing an exit ahead.

Presently it peeled off from the parkway, then speeded up again along a narrow road whose surface rapidly disintegrated into a barely visible grass-covered track. Washington took the steering lever just a second before the END AUTO warning light started to flash on the control panel.

“I’m taking you to the farm for several reasons,” he said. “Life will soon get hectic for both of us, as more visitors start arriving. This may be the last opportunity we have to go through your program in peace and quiet.

Also, out-worlders can learn a lot about Earth very quickly in a place like this. But to be honest-the truth is that I’m proud of the place, and like showing it off.”

They were now approaching a high stone wall, running for hundreds of meters in both directions. Duncan tried to calculate how much labor it represented, if all those oddly shaped blocks were assembled by hand-as surely they must have been. The figure was so incredible that he

couldn’t believe it. And that huge gate was made of-genuine wood, 116 for it was unpainted and he could see the grain. As it swung automatically open, Duncan read the nameplate, and turned to the Professor in surprise.

“But I thought-” he began.

George Washington looked slightly embarrassed.

“That’s my private joke,” he admitted. “The real Mount Vernon is fifty kilometers southeast of here. You mustn’t miss it.”

That last phrase, Duncan guessed, was going to become all too familiar in the months ahead-right up to the day when he reembarked for Titan.

Inside the walls, the road-now firm-packed gravel -ran in a straight line through a checkerboard of small fields. Some of the fields were plowed, and there was a tractor working in one of them-under direct human control, for a man was sitting on the open driving seat. Duncan felt that he had indeed traveled back in time.

“I suppose there’s no need to explain,” said the Professor, “that all this doesn’t belong to me. It’s owned by the Smithsonian. Some people complain that everything within a hundred kilometers of the Capitol is owned by the

Smithsonian, but that’s a slight exaggeration. I’m just the administrator; you might say it’s a kind of full-time hobby. Every year I have to submit a report, and as long as I do a good job, and don’t have a fight with the

Regents, this is my home. Needless to say, I am careful to keep on excellent terms with at least fifty-one percent of the Regents. By the way, do you recognize any of these crops?”

“I’m afraid not-though that’s grass, isn’t it?”

“Well, technically, almost everything here is. Grass includes all the cereals-barley, rice, maize, wheat, oats…. We grow them all except rice.”

“But why-I mean, except for scientific and archaeological interest?”

“Isn’t that sufficient? But I think you’ll find there’s more to it than that, when you’ve had a look around.”

At the risk of being impolite, Duncan persisted. He was not trying to be stubborn, but was genuinely interested.

“What about efficiency? Doesn’t it take a square kilometer to feed one

man, with this system?” “Out around Saturn, perhaps; I’m afraid you’ve dropped a few zeros. If it had to, this little farm could support fifty people in fair comfort, though their diet would be rather monotonous.”

“I’d no idea-my God, what’s that?”

“You’re joking-you don’t recognize it?”

“Oh, I know it’s a horse. But it’s enormous. I thought…”

“Well, I can’t blame you, though wait until you see an elephant.

Charlemagne is probably the largest horse alive today. He’s a Percheron, and weighs over a ton. His ancestors used to carry knights in full armor.

Like to meet him?”

Duncan wanted to say “Not really,” but it was too late. Washington brought the car to a halt, and the gigantic creature ambled toward them.

Until this moment, the limousine had been closed and they had been traveling in air-conditioned comfort. Now the windows slid down-and

Primeval Earth hit Duncan full in the nostrils.

“What’s the matter?” asked Washington anxiously. “Are you all right?”

Duncan gulped, and took a cautious sniff.

“I think so,” he said, without much conviction. “IVS just that-the air is rather—2’ He struggled for words as well as breath, and had almost selected “ripe’ when he gratefully switched to “rich” in the nick of time.

“I’m so sorry,” apologized Washington, genuinely contrite. “I’d quite forgotten how strange this must be -to you. Let me close the window. Go away, Charlie -sorry, some other time.”

The monster now completely dwarfed the car, and a huge head, half as big as a man, was trying to insert itself through the partially open window on

Duncan’s side. The air became even thicker, and redolent of more animal secretions than he cared to identify. Two huge, slobbering lips drew back, to disclose a perfectly terrifying set of teeth…. “Oh, very well,” said Professor Washington in a resigned voice. He leaned across his cowering guest, holding out an open palm on which two lumps of sugar had magically appeared. Gently as any maiden’s kiss, the lips nuzzled

Washington’s hand, and the gift 118 vanished as if inhaled. A mild, gentle eye, which from this distance seemed about as large as a fist, looked straight at Duncan, who started to laugh a little hysterically as the apparition withdrew.

“What’s so funny?” asked Washington.

“Look at it from my point of view. I’ve just met my first Monster from

Outer Space. Thank God it was friendly.”

THE TASTE OF HONEY

I do hope you slept well,” said George Washington, as they walked out into the bright summer morning.

“Quite well, thank you,” Duncan answered, stifling a yawn. He only wished that the statement were true.

It had been almost as bad as his first night aboard Sirius. Then, the noises had all been mechanical. This time, they were made by-things.

Leaving the window open had been a big mistake, but who could have guessed?

“We don’t need air conditioning this time of year,” George had explained.

“Which is just as well, because we haven’t got it. The Regents weren’t too happy even about electric light in a four-hundred-year-old house. If you do get too cold, here are some extra blankets. Primitive, but very effective.”

Duncan did not get too cold; the night was pleasantly mild. It was also extremely busy.

There had been distant thumpings which, he eventually decided, must have been Charlie moving his thousand kilos of muscle around the fields. There had been strange squeakings and rustlings apparently just outside his window, and one high-pitched squeal, suddenly

terminated, which could only have been caused by some unfortunate small beast meeting an untimely end.

But at last he dozed off-only to be wakened, quite suddenly, by the most horrible of all the sensations that can be experienced by a man in the utter darkness of an unfamiliar bedchamber. Something was moving around the room.

It was moving almost silently, yet with amazing speed. There was a kind of whispering rush and, occasionally, a ghostly squeaking so high-pitched that at first Duncan wondered if he was imagining the entire phenomenon. After some minutes he decided, reluctantly, that it was real enough. Whatever the thing might be, it was obviously airborne. But what could possibly move at such speed, in total darkness, without colliding with the fittings and furniture of the bedroom?

While he considered this problem, Duncan did what any sensible man would do. He burrowed under the bedclothes, and presently, to his vast relief, the whispering phantom, with a few more shrill gibberings, swooped out into the night. When his nerves had fully recovered, Duncan hopped out of bed and closed the window; but it seemed hours before his nervous system settled down again.

In the bright light of morning, his fears seemed as foolish as they doubtless were, and he decided not to ask George any questions about his nocturnal visitor; presumably it was some night bird or large insect. Everyone knew that there were no dangerous animals left on Earth, except in well-guarded reservations…. Yet the creatures that George now seemed bent on introducing to him looked distinctly menacing. Unlike Charlemagne, they had built-in weapons.

“I suppose,” said George, only half doubtfully, “that you recognize these?”

“Of course-I do know some Terran zoology. If it has a leg at each corner, and horns, it’s not a horse, but a cow.”

“I’ll only give you half marks. Not all cows have horns. And for that matter, there used to be homed horses. But they became extinct when

there were no more virgins to bridle them.” Duncan was still trying to decide if this was a joke, and if so what was the point of it, when he had a slight mishap.

“Sorry!” exclaimed George, “I should have warned you to mind your step.

Just rub it off on that tuft of grass.”

“Well, at least it doesn’t smell quite as bad as it looks,” said Duncan resignedly, determined to make the best of a bad job.

“That’s because cows are herbivores. Though they’re not very bright, they’re sweet, clean animals. No wonder they used to worship them in India.

Hello, Daisy-morning, Ruby-now, Clemence, that was naughty-Tv

It seemed to Duncan that these bovine endearments were rather one-sided, for their recipients gave no detectable reaction. Then his attention was suddenly diverted; something quite incredible was flying toward them.

It was small-its wingspan could not have been more than ten centimeters-and it traced wavering, zigzag patterns through the air, often seeming about to land on a low bush or patch of grass, then changing its mind at the last moment. Like a living jewel, it blazed with all the colors of the rainbow; its beauty struck Duncan like a sudden revelation. Yet at the same time he found himself asking what purpose such exuberant-no, arrogant-loveliness could possibly serve.

“What is it?” he whispered to his companion, as the creature swept aimlessly back and forth a couple of meters above the grass.

“Sorry,” said George. “I can’t identify it. I don’t think it’s indigenous, though I may be wrong. We get a lot of migrants nowadays, and sometimes they escape from collectors-breeding them’s been a popular hobby for years.” Then he stopped. He had suddenly understood the real thrust of

Duncan’s question. There was something close to pity in his eyes when he continued, in quite a different tone of voice:

“I should, have explained-it’s a butterfly.”

But Duncan scarcely heard him. That iridescent creature, drifting so

effortlessly through the air, made him forget the ferocious gravitational field of which he was now a captive.

He started to ran toward it with the inevitable result.

Luckily, he landed on a clean patch of grass.

Half an hour later, feeling quite comfortable but rather foolish, Duncan was sitting in the centuries old farmhouse with his bandaged ankle stretched out on a footstool, while Mrs. Washington and her two young daughters prepared lunch. He had been carried back like a wounded warrior from the battlefield by a couple of tough farm workers who handled his weight with contemptuous ease, and also, he could not help noticing, radiated a distinct aroma of Charlemagne…. It must be strange, he thought, to live in what was virtually a museum, even as a kind of part-time hobby; he would have been continually afraid of d aging some priceless artifact—such as the spinning wheel that Mrs.

Washington had demonstrated to him. At the same time, he could appreciate that all this activity made a good deal of sense. There was no other way in which you could really get to understand the past, and there were still many people on earth who found this an attractive way of life. The twenty or so farm workers, for example, were here permanently, summer and winter.

Indeed, he found it rather hard to imagine some of them in any other environment even after they had been thoroughly scrubbed…. But the kitchen was spotless, and a most attractive smell was floating from it. Duncan could recognize very few of its ingredients, but one was unmistakable, even though he had met it today for the first time in his life. It was the mouth-watering fragrance of newly baked bread.

It would be all right, he assured his still slightly queasy stomach. He had to ignore the undeniable fact that everything on the table was grown from dirt and dung, and not synthesized from nice, clean chemicals in a spotless factory. This was how the human race had lived for almost the whole of its history; only in the last few seconds of

time had there been any alternative. For one gut-wrenching moment, until Washington had reassured him, he had feared that he might be served real meat. Apparently it was still available, and there was no actual law against it, though many attempts had been made to pass one. Those who opposed Prohibition pointed out that attempts to enforce morality by legislation were always counterproductive; if meat were banned, everybody would want it, even if it made them sick.

And anyway, this was a perversion which did harm to nobody…. Not so, retorted the Prohibitionists; it would do irreparable harm to countless innocent animals, and revive the revolting trade of the butcher. The debate continued, with no end in sight.

Confident that lunch would present mysteries but no terrors, Duncan did his best to enjoy himself. On the whole he succeeded. He bravely tackled everything set before him, rejecting about a third after one nibble, tolerating another third, and thoroughly appreciating the remainder. As it turned out, there was nothing that he actively disliked, but several items had flavors that were too strange and complicated to appeal to him at first taste.

Cheese, for example that was a complete novelty. There were about six different kinds, and he nibbled at them all. He felt that he could get quite enthusiastic about at least two varieties, if he worked on it. But that might not be a good idea, for it was notoriously difficult to persuade the Titan food chemists to introduce new patterns into their synthesizers.

Some products were quite familiar. Potatoes and tomatoes, it seemed, tasted much the same all over the Solar System. He had already encountered them, as luxury products of the hydroponic farms, but had always found it difficult to get enthusiastic about either, at several so lars a kilogram.

The main dish was-well, interesting. It was something called steak and kidney pie, and perhaps the unfortunate name turned him off. He knew perfectly well that the contents were based on high-protein soya; Washington had confessed that this was the only item not actually

produced on the farm, because the, technology needed was too elaborate. Nevertheless, he could not manage more than a few bites. It was too bad that every time he tried to take a mouthful, he kept thinking of the phrase “kidney function” and its unhappy associations. But the crust of the pie was delicious, and he polished off more than half of it.

Dessert was no problem. It consisted of a large variety of fruits, most of them unfamiliar to Duncan even by name. Some were insipid, others very pleasant, but he felt that all were perfectly safe. The strawberries he thought especially good, though he turned down the cream that was offered with them when he discovered, by tactful questioning, exactly how it was made.

He was comfortably replete when Mrs. Washington produced a final surprise-a small wooden box containing a wax honeycomb. As long as he could remember,

Duncan had been familiar with that term for lightweight structures; it required a mental volte face to realize that this was the genuine, original item constructed by Terran insects.

“We’ve just started keeping bees,” explained the Professor. “Fascinating creatures, but we’re still not sure if they’re worth the trouble. I think you’ll like this honey-try it on this crust of new bread.”

His hosts watched him anxiously as he spread the golden fluid, which he thought looked exactly like lubricating off. He hoped that it would taste better, but he was now prepared for almost anything.

There was a long silence. Then he took another bite-and another.

“Well?” asked George at last.

“It’s-delicious-one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.”

“I’m so pleased,” said Mrs. Washington. “George, be sure to send some to the hotel for Mr. Makenzie.”

Mr. Makenzie continued to sample the bread and honey, very slowly. There was a remote and abstracted expression on his face, which his delighted hosts attributed to sheer gastronomical-pleasure. They could not possibly have guessed at the real reason. Duncan had never

been particularly interested in 124 food, and had made no effort to try the occasional novelties that were imported into Titan. The few times that any had been pressed upon him, he had not enjoyed them; he still grimaced at the memory of a reputed delicacy called caviar. He was therefore absolutely certain that never before in his life had he tasted honey.

Yet he recognized it at once; and that was only half the mystery. Like a name that is on the tip of the tongue, yet eludes all attempts to grasp it, the memory of that earlier encounter lay just below the level of consciousness. It had happened a long time ago-but when, and where? For a fleeting moment he almost took seriously the idea of reincarnation. You,

Duncan Makenzie, were a beekeeper in some earlier life on Earth…. Perhaps he was mistaken in thinking that he knew the taste. The association could have been triggered by some random leakage between mental circuits.

And anyway, it could not possibly be of the slightest importance…. He knew better. Somehow, it was very important indeed.

HISTORY LESSON

Of all the old cities, it was generally agreed that Paris and Washington offered the best combination of beauty, culture, history-and convenience Unlike such largely random aggregations as London and Rome, which had defied millennia of planning, they had been adapted fairly easily to automatic transportation. Could he have risen from his tomb in Arlington, the luckless Pierre Charles

L’Enfant would have been proud indeed to have discovered how well he had laid the ground for a technology centuries in his future.

Though an official car was available whenever he wished, Duncan preferred to be as independent as possible. Coming from an aggressively egalitarian society, he never felt quite happy when he was afforded special privileges-except, of course, those he had earned himself. Now that his sprained ankle was no longer paining him he had no excuse for using personal transport, and one could never know a city until one had explored it on foot.

Like any ordinary tourist-and Washington expected the incredible total of five million before the end of July-Duncan rode the glide ways and auto jitneys gaping at the famous buildings and remembering the great men who had lived and worked here for half a thousand years. In the five-kilometer-long rectangle from the Lincoln Memorial to the Capitol, and from the Washington Monument to the White House, no changes had been permitted for more than a century. To ride the shuttle down Constitution

Avenue and back along Independence, on the south side of the Mall, was to take a journey through time.

And time was the problem, for Duncan could spare only an hour or two a day for sightseeing. His planned schedule had already been wrecked by a factor that he had refused to take seriously, despite numerous warnings. Instead of his usual six, he needed no fewer than ten hours of sleep every day.

This was yet another side effect of the increased gravity, and there was nothing he could do about it; his body stubbornly insisted on the additional time, to overcome the extra wear and tear. Eventually, he knew, he would make a partial adaptation, but he could hardly hope to manage with less than eight hours. It was maddening to have come all this way, to one of the most fascinating places on Earth, and to be compelled to waste more than forty percent of his life in unconsciousness.

As with most off-worlders, his first target had been the National Museum of

Astronautics on the Mall, because. it was here that his own history

had begun, 126 that day in July 1969. He had walked past the flimsy and improbable hardware of the early Space Age, and had taken his seat with several hundred other visitors in the Apollo Rotunda just before the beginning of the half-hourly show.

There was nothing that he had not seen many times before, yet the old drama still gripped him. Here were the faces of the first men to ride these crazy contraptions into space, and the sound of their actual voices-sometimes emotionless, sometimes full of excitement-as they spoke to their colleagues on the receding Earth. Now the air shook with the crackling roar of a

Saturn launch, magically recreated exactly as it had taken place on that bright Florida morning, three hundred and seven years ago-and still, in many ways, the most impressive spectacle ever staged by man.

The Moon drew closer-not the busy world that Duncan knew, but the virgin

Moon of the twentieth century. Hard to imagine what it must have meant to people of that time, to whom the Earth was not only the center of the

Universe, but-even to the most sophisticated-still the whole of creation…. Now Man’s first contact with another world was barely minutes ahead. It seemed to Duncan that he was floating in space, only meters away from the spidery Lunar Module, bristling with antennas and wrapped in multicolored metal foil. The simulation was so perfect that he had an involuntary urge to hold his breath, and found himself clutching the handrail, seeking reassurance that he was still on Earth.

“Two minutes, twenty seconds, everything looking good. We show altitude about 47,000 feet…” said Houston to the waiting world of 1969, and to the centuries to come. And then, cutting across the voice of Mission

Control, making a montage of conflicting accents, was a speaker whom for a moment Duncan could not identify, though he knew the voice…. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning

him safely to the Earth.” Even back in 1969, that was already a voice from the grave; the President who had launched Apollo in that speech to Congress had never lived to see the achievement of his dream.

“We’re now in the approach phase, everything looking good. Altitude 5,200 feet.”

And once again that voice, silenced six years earlier in Dallas:

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people….”

“Roger. Go for landing, 3,000 feet. We’re go. Hang tight. We’re go. 2,000 feet. 2,000 feet…”

“And why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal … ? Why, thirty-five years ago, fly the Atlantic? WE CHOOSE TO GO TO THE MOON!” “200 feet, 41/2 down, 51h down, 160, 61h down, 5V2 down, 9 forward, 120 feet, 100 feet, 31h down, 9 forward, 75 feet, things still looking good..”

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade because that challenge is one that we’re willing to accept, one that we are unwilling to postpone, and one that we intend to win!”

“Forward, forward 40 feet, down 21h, kicking up some dust, 30 feet, 21h down, faint shadow, 4 forward, 4 forward, drifting to the right a little . . Contact light. O.K. engine stopped, descent engine command ove ride off … Houston, Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

The music rose to a crescendo. There before his eyes, on the dusty Lunar plain, history had lived again. And presently he saw the clumsy, spacesuited figure climb down the ladder, cautiously test the alien soil, and utter the famous words:

“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

As always, Duncan listened for that missing 64a9l before the word “man,” and as always, he was unable to detect it. A whole book had been written about that odd slip of the tongue, using as its starting point Neil

Armstrong’s slightly exasperated “That’s what I intended to say, and

that’s what I thought I said.” 128 All of this, of course, was simulation-utterly convincing, and apparently life-sized by the magic of holography-but actually contrived in some studio by patient technicians, two centuries after the events themselves. There was Eagle, glittering in the fierce sunlight, with the Stars and Stripes frozen motionless beside it, just as it must have appeared early in the

Lunar morning of that first day. Then the music became quiet, mysterious . something was about to happen. Even though he knew what to expect, Duncan felt his skin crawling in the ancient, involuntary reflex which Man had inherited from his hirsute ancestors.

The image faded, dissolved into another—similar, yet different. In a fraction of a second, three centuries had dropped away.

They were still on the Moon, viewing the Sea of Tranquillity from exactly the same vantage point. But the direction of the light had changed, for the sun was now low and the long shadows threw into relief all the myriads of footprints on the trampled ground. And there stood all that was left of

Eagle-the slightly peeled and blistered descent stage, standing on its four outstretched legs like some abandoned robot.

He was seeing Tranquillity Base as it was at this instant-or, to be precise, a second and a quarter ago, when the video signals left the Moon.

Again, the illusion was perfect; Duncan felt that he could walk out into that shining silence and feel the warm metal beneath his hands. Or he could reach down into the dust and lift up the flag, to end the old debate that had reerapted in this Centennial Year. Should the Stars and Stripes be left where the blast of the takeoff had thrown it, or should it be erected again? Don’t tamper with history, said some. Were only restoring it, said others…. Something was happening just beyond the fence doff area, at the very limits of the 3-D scanners. It was shockingly incongruous to see any movement at all at such a spot; then Duncan remembered that the Sea had lost its tranquillity at least two

centuries ago. A busful of tourists was slowly circling the landing site, its occupants in full View through the curving glass of the observation windows. And though they could not see him, they waved across at the scanners, correctly guessing that someone on Earth was watching at this very moment.