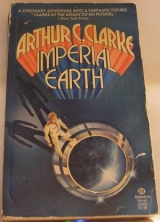

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

It was a timely reminder of his own responsibilities. While the voyage was still beginning, he had better start work.

Exactly ten minutes, George Washington had directed-not a second more. Even the President will be allowed only fifteen, and all the planets must have equal time. The whole affair is scheduled to last two and a half hours, from the moment we enter the Capitol until we leave for the reception at the White House…. It still seemed faintly absurd to travel three billion kilometers to make a ten-minute speech, even for an occasion as unique as a five-hundredth anniversary. Duncan was not going to waste more than the bare minimum of it on polite formalities; anyway, as Malcolm had pointed out, the sincerity of a speech of thanks

is often inversely proportional to its length. For his amusement-and, more important, because it would help to fix the other participants in his mind -Duncan had tried to compose a formal opening, based on the list of guests that Professor Washington had provided. It started off: “Madame President, Mr. Vice President, Honorable

Chief Justice, Honorable Leader of the Senate, Honorable Leader of the

House, Your Excellencies the Ambassadors for Luna, Mars, Mercury, Ganymede, and Titan”-at this point he would incline his head slightly toward

Ambassador Farrell, if he could see him in the crowded gallery’distinguished representatives from Albania, Austrand, Cyprus, Bohemia,

France, Khmer, Palestine,

Kalinga, Zimbawe, Eire He calculated that if he acknowledged all the fifty or sixty regions that still insisted on some form of individual recognition, a quarter of his time would be expended before he had even begun. This, obviously, was absurd, and he hoped that all the other speakers would agree. Regardless of protocol, Duncan had decided to opt for dignified brevity.

“People of Earth” would cover a lot of ground-to be precise, five times the area of Titan, an impressive statistic which Duncan knew by heart. But that would leave out the visitors; what about “Friends from other worlds”? No, that was too pretentious, since most of them would be complete strangers.

Perhaps: “Madame President, distinguished guests, known and unknown friends from many worlds…” That was better, yet somehow it still didn’t seem right.

There was more to this business, Duncan realized, than met the eye, or the ear. Plenty of people would be willing to give him advice, but he was determined, in the good old Makenzie tradition, to see what he could do himself before calling for help. He had read somewhere that the best way to learn to swim is by being thrown into deep water. Duncan could not swim -that skill being singularly useless on Titan-but he could appreciate the analogy. His career in Solar politics would start with a spectacular splash, and before the eyes of millions.

It was not that he was nervous; after all, he had addressed his whole

world as an expert witness during technical debates in the Assembly. He had acquitted himself well when he weighed the complex arguments for and against mining the ammonia glaciers of

Mount Nansen. Even Armand Helmer had congratulated him, despite the fact that they had reached opposing conclusions. In those debates, affecting the future of Titan, he had had real responsibility, and his career might have come to an abrupt end if he had made a fool of himself. His Terran audience might be a thousand times larger, but it would be very much less critical. Indeed, his listeners would be friendly unless he committed the unpardonable sin of boring them.

This, however, he could not yet guarantee, for he still had no idea how he was going to use the most important ten minutes of his life.

Is

AT THE NODE

0 n the seas of Earth, they had called it

“Crossing the Line.” Whenever a ship had passed from one hemisphere to another, there had been light hearted ceremonies and rituals, during which those who had never traversed the Equator before were subjec I ted to ingenious indignities by Father Neptune and his Court.

During the first centuries of space flight, the equivalent transition involved no physical changes; only the navigational computer knew when a ship had ceased to fall toward one planet and was beginning to fall toward another. But now, with the advent of constant acceleration drives, which could maintain thrust for the entire duration of a voyage, Midpoint, or

“Turnaround,” had a real physical meaning, and a correspondingly enhanced psychological impact. After living and moving for days in an

apparent gravitational field, 84 Sirius’ passengers would lose all weight for several hours, and could at least feel that they were really in space.

They could watch the slow rotation of the stars as the ship was swung through one hundred eighty degrees, and the drive was aimed precisely against its previous line of thrust, to slowly whittle away the enormous velocity built up over the preceding ten days. They could savor the thought that they were now moving faster than any human beings in history-and could also contemplate the exciting prospect that if the drive failed to restart,

Sirius would ultimately reach the nearest stars, in not much more than a thousand years…. All these things they could do; however, human nature having certain invariants, a majority of Sirius’ passengers had other possibilities in mind.

It was the only chance most of them would ever have of experiencing weightlessness long enough to enjoy it. What a crime to waste the opportunity! No wonder that the most popular item in the ship’s library these last few days had been the Nasa Sutra, an old book and an old joke, explained so often that it was no longer funny.

Captain Ivanov denied, with a reasonably convincing show of indignation, that the ship’s schedule had been designed to pander to the passenger’s lower instincts. When the subject had been raised at the Captain’s table, the day before Turnaround, he had put up quite a plausible defense.

“It’s the only logical time to shut down the Drive,” he had explained.

“Between zero zero and zero four, all the passengers will be in their cabins, er, sleeping. So there will be the minimum of disturbance. We couldn’t close down during the day-remember, the kitchens and the toilets will be out of action while we’re weightless. Don’t forget that! We’ll remind everyone in the late evening, but some idiot always gets overconfident, or drinks too much, and doesn’t have enough sense to read the instructions on those little plastic bags you’ll find in your cabins-no thanks, Steward, I don’t feel like soup.”

Duncan had been tempted; Marissa was beginning to fade, and there was no lack of opportunity. He had received unmistakable signals from several directions, and for groups with all values of n from one to five. It would not have been easy to make a choice, but Fate had saved him the trouble.

It was a full week, and Turnaround was only three days ahead, before he had felt confident enough of his increasing intimacy with Chief Engineer

Mackenzie to drop some gentle hints. They had not been rejected out of hand, but Warren obviously wanted time to weigh the possibilities. He gave

Duncan his decision only twelve hours in advance.

“I won’t pretend this might cost me nay job,” he said, “but it could be embarrassing, to say the least, if it got around. But you are a Makenzie, and a Special Assistant to the Administrator, and all that. If the worst comes to the worst, which I hope it won’t, we can say your request’s official.”

“Of course. I understand completely, and I really appreciate what you’re doing. I won’t let you down.” . “Now there’s the question of timing. If everything checks out smoothly-and I’ve no reason to expect otherwise-I’ll be through in two hours and can dismiss my assistants. They’ll leave like meteors-they’ll all have something lined up, you can be sure of that -so we’ll have the place to ourselves. I’ll give you a call at zero two, or as soon after as possible.”

“I hope I’m not interrupting any~ ah-personal plans you’ve made.”

“As it happens, no. The novelty’s worn off. What are you smiling at?”

“It’s just occurred to me,” Duncan answered, “that if anyone does meet the pair of us at two o’clock on the morning of Turnaround, we’ll have a perfect alibi …. “

Nevertheless, he felt a mild sense of guilt as he drifted along the corridors behind Warren Mackenzie. The weightless-but far from sleeping-ship might have been deserted, for there was no occasion now for anyone to descend below the freight deck on Level Three. It was not even necessary to pretend that they were heading for an innocent assignation.

Yet the guilt was there, and he knew why. He was taking advantage of a friendship for secret purposes of his own, by suggesting that his interest in the Asymptotic Drive was no more than would be expected from anyone with a scientific or engineering background. But perhaps Warren was not as naieve as he seemed; he could hardly be unaware that the Drive posed a threat to the entire economy of Duncan’s society. He might even be trying to help, in a tactful way.

“You may be disappointed,” said Warren as they passed through the bulkhead floor separating levels Three and Two. “There’s not much to see. But what there is is enough to give some people nightmares which is why we discourage visitors.”

Not the most important reason, thought Duncan. The Drive was not exactly a secret; there was an immense literature on the subject, from the most esoteric mathematical papers down to popularizations so elementary that they amounted to little more than: “You pull on your bootstraps, and away you go.” But it would be fair to say that Earth’s Space Transportation

Authority was curiously evasive when it came down to the practical details, and only its own personnel were allowed on the minor planet where the Drive was assembled. The few photos of Asteroid 4587 were blurred telescopic shots showing two cylindrical structures, more than a thousand kilometers long, stretching out into space on either side of the tiny world, which was an almost invisible speck between them. It was known that these were the accelerators that smashed matter together at such velocities that it fused to form the node or singularity at the heart of the Drive; and this was all that anyone did know, outside the

STA.

Duncan was now floating, a few meters behind his guide, along a corridor lined with pipes and cable ducts-all the anonymous plumbing any vehicle of sea, air, or space for the last three hundred years. Only the remarkable number of handholds, and the profusion of thick padding, revealed that this was the interior of a ship designed to be independent of gravity.

“D’you see that pipe?” said the engineer. “The little red one?”

“Yes-what about it?” Duncan would certainly never have given it a second glance; it was only about as thick as a lead pencil.

“That’s the main hydrogen feed, believe it or not. All of a hundred grams a second. Say eight tons a day, under full thrust.”

Duncan wondered what the old-time rocket engineers would have thought of this tiny fuel line. He tried to visualize the monstrous pipes and pumps of the Saturns that had first taken men to the Moon; what was their rate of fuel consumption? He was certain that they burned more in every second than Sirius consumed in a day. That was a good measure of how far technology had progressed, in three centuries. And in another three … ?

“Mind your head-those are the deflection coils. We don’t trust room-temperature superconductors. These are still good old cryogenics.”

“Deflection coils? What for?”

“Ever stopped to think what would happen if that jet accidentally touched part of the ship? These coils keep it centered, and also give all the vector control we need.”

They were now hovering beside a massive-yet still surprisingly small-cylinder that might have been the barrel of a twentieth-century naval gun. So this was the reaction chamber of the Drive. It was hard not to feel a sense of almost superstitious awe at the knowledge of what lay within a few centimeters of him. Duncan could easily have encircled the metal tube with his arms; how strange to think of putting your arms around a singularity, and thus, if some of the theories were correct, embracing an entire universe…. Near the middle of the five-meter-long tube a small section of the casing had been removed, like the door of some miniature bank vault, and replaced by a crystal window. Through this obviously temporary opening a microscope, mounted on a swinging arm so that it could be moved away after use, was aimed into the interior of the drive unit.

The engineer clipped himself into position by the buckles conveniently fixed to the casing, stared through the eyepiece, and made some

delicate micrometer adjustments. “Take a look,” he said, when he was finally satisfied.

Duncan floated to the eyepiece and fastened himself rather clumsily in place. He did not know what he had expected to see, and he remembered that the eye had to be educated before it could pass intelligible impressions to the brain. Anything utterly i!nfamiliar could be, quite literally, invisible, so he was not too disappointed at his first view.

What he saw was, indeed, perfectly ordinary merely a grid of fine hairlines, crossing at right angles to form a reticule of the kind commonly used for optical measurements. Though he searched the brightly lit field of view, he could find nothing else; he might have been exploring a piece of blank graph paper.

“Look at the crossover at the exact center,” said his guide, “and turn the knob on the left-very slowly. Half a rev will do-either direction.”

Duncan obeyed, yet for a few seconds he could still see nothing. Then be realized that a tiny bulge was creeping along the hairline as he tracked the microscope. It was as if he was looking at the reticule through a sheet of glass with one minute bubble or imperfection in it.

“Do you see it?”

“Yes-just. Like a pin head-sized lens. Without the grid, you’d never notice it.”

“Pinbead-sized! That’s an exaggeration, if ever I heard one. The node’s smaller than an atomic nucleus. You’re not actually seeing it, of course-only the distortion it produces.”

“And yet there are thousands of tons of matter in there.”

“Well, one or two thousand,” answered the engivneer, rather evasively.

“It’s made a dozen trips and is getting near saturation, so we’ll soon have to install a new one. Of course it would go on absorbing hydrogen as long as we fed it, but we can’t drag too much unnecessary mass around, or we’ll pay for it in performance. Like the old seagoing ships-they used to get covered with barnacles, and slowed down if they weren’t scraped clean every so often.”

“What do they do with old nodes when they’re too massive to use? Is it true that they’re dropped into the sun?”

“What good would that do? A node would sail right through the sun and out the other side. Frankly, I don’t know what they do with the old ones.

Perhaps they lump them all together into a big granddaddy node, smaller than a neutron but weighing a few million tons.”

There were a dozen other questions that Duncan was longing to ask. How were these tiny yet immensely massive objects handled? Now that Sirius was in free fall, the node would remain floating where it was-but what kept it from shooting out of the drive tube as soon as acceleration started? He assumed that some combination of powerful electric and magnetic fields held it in place, and transmitted its thrust to the ship.

“What would happen,” Duncan asked, “if I tried to touch it?”

“You know, absolutely everyone asks that question.”

“I’m not surprised. What’s the answer?”

“Well, you’d have to open the vacuum seal, and then all hell would break loose as the air rushed in.”

“Then I don’t do it that way. I wear a spacesuit, and I crawl up the drive tunnel and reach out a finger … to

“How clever of you to hit exactly the right spot! But if you did, when your finger tip got within—oh -something like a millimeter, I’d guess-the gravitational tidal forces would start to tear away at it. As soon as the first few atoms fell into the field, they’d give up all their mass-energy-and you’d think that a small hydrogen bomb had gone off in your face. The explosion would probably blow you out of the tube at a fair fraction of the speed of light.”

Duncan gave an uncomfortable little laugh.

“It would certainly take a clever man to steal one of your babies. Doesn’t it ever give you nightmares?”

“No. It’s the tool I’m trained to use, and I understand its little ways. I can’t imagine handling power lasers-they scare the hell out of

me. You know, old Kipling had it all summed up, as usual. You remember me talking about him?”

“Yes.”

“He wrote a poem called “The Secret of the Machines,” and it has some lines

I often say to myself when I’m down here:

“But remember, please, the Law by which we live,

We are not built to comprehend a lie,

We can neither love nor pity nor forgive.

If you make a slip in handling us you die!

“And that’s true of all machines-all the natural forces we’ve ever learned to handle. There’s no real difference between the first caveman’s fire and the node in the heart of the Asymptotic Drive.”

An hour later, Duncan lay sleepless in his bunk, waiting for the Drive to go on and for Sirius to begin the ten days of deceleration that would lead to her rendezvous with Earth. He could still see that tiny flaw in the structure of space, hanging there in the field of the microscope, and knew that its image would haunt him for the rest of his life. And he realized now that Warren Mackenzie had betrayed nothing of his trust; all that he had learned had been published a thousand times. But no words or photos could ever convey the emotional impact he had experienced.

Tiny fingers began to tug at him; weight was returning to Sirius. From an infinite distance came the thin wail of the Drive; Duncan told himself that he was listening to the death cry of matter as it left the known universe, bequeathing to the ship all the energy of its mass in the final moment of dissolution. Every minute, several kilograms of hydrogen were falling into that tiny but insatiable vortex-the hole that could never be filled.

Duncan slept poorly for the rest of the night. He had dreams that he too was Falling, falling into a spinning whirlpool, indefinitely deep. As he fell, he was being crushed to molecular, to atomic, and finally

to sub nuclear dimensions. In a moment, it would all be over, and he would disappear in a single flash of radiation…. But that moment never came, because as Space contracted, Time stretched endlessly, the passing seconds becoming longer… and longer… and longer -until he was trapped forever in a changeless Eternity.

PORT VAN ALLEN

When Duncan had gone to bed for the last time aboard Sirius, Earth was still five million kilometers away. Now it seemed to fill the sky-and it was exactly like the photographs. He had laughed when more seasoned travelers told him he would be surprised at this; now he was ruefully surprised at his surprise.

Because the ship had cut right across the Earth’s orbit, they were approaching from sunward, and the hemisphere below was almost fully illuminated. White continents of cloud covered most of the day side, and there were only rare glimpses of land, impossible to identify without a map. The dazzling glare of the Antarctic icecap was the most prominent surface feature; it looked very cold down there, yet Duncan reminded himself that it was tropical in comparison with much of his world.

Earth was a beautiful planet; that was beyond dispute. But it was also alien, and its cool whites and blues did nothing to warm his heart. It was indeed a paradox that Titan, with its cheerful orange clouds, looked so much more hospitable from space.

Duncan stayed in Lounge B, watching the approaching Earth and making his farewells to many temporary friends, until Port Van Allen was a

dazzling star against the blackness of space, then a glittering ring, then a huge, slowly turning wheel. Weight gradually ebbed away as the drive that had taken them halfway across the Solar System decreased its thrust to zero; then there were only occasional nudges as low-powered thrustors trimmed the attitude of the ship.

The space station continued to expand. Its size was incredible, even when one realized that it had been steadily growing for almost three centuries.

Now it completely eclipsed the planet whose commerce it directed and controlled; a moment later a barely perceptible vibration, instantly damped out, informed everyone that the ship had docked. A few seconds later, the Captain confirmed it.

“Welcome to Port Van Allen-Gateway to Earth. It’s been nice having you with us, and I hope you enjoy your stay. Please follow the stewards, and check that you’ve left nothing in your cabins. And I’m sorry to mention this, but three passengers still haven’t settled their accounts. The Purser will be waiting for them at the exit….”

A few derisive groans and cheers greeted this announcement, but were quickly lost in the noisy bustle of disembarkation. Although everything was supposed to have been carefully planned, chaos was rampant. The wrong passengers went to the wrong checkpoints, while the public-address system called plaintively for individuals with improbable names. It took Duncan more than an hour to get into the spaceport, and he did not see all of his baggage again until his second day on Earth.

But at last the confusion abated as people squeezed through the bottleneck of the docking hub and sorted themselves out in the appropriate levels of the station. Duncan followed instructions conscientiously, and eventually found himself, with the rest of his alphabetical group, lined up outside the Quarantine Office. All other formalities had been completed hours ago, by radio circuit; but this was something that could not be done by electronics. Occasionally,

travelers had been turned back at this point, on the very door step of Earth, and it was not without qualms that Duncan confronted this last hurdle.

“We don’t get many visitors from Titan,” said the medical officer who checked his record. “You come in the Lunar classification-less than a quarter gee. It may be tough down there for the first week, but you’re young enough to adapt. It helps if both your parents were born…”

The doctor’s voice trailed off into silence; he had come to the entry marked MOTHER. Duncan was used to the reaction, and it had long ago ceased to bother him. Indeed, he now derived a certain amusement from the surprise that discovery of his status usually produced. At least the M.O. would not ask the silly question that laymen so often asked, and to which he had long ago formulated an automatic reply: “Of course I’ve got a navel-the best that money can buy.” The other common myth-that male clones must be abnormally virile “because the had one father twice”-he had wisely left unchY lenged. It had been useful to him on several occasions.

Perhaps because there were six other people waiting in line, the doctor suppressed any scientific curiosity he may have felt, and sent Duncan “upstairs” to the Earth-gravity section of the spaceport. It seemed a long time before the elevator, moving out along one of the spokes of the slowly spinning wheel, finally reached the rim; and all the while, Duncan felt his weight increasing remorselessly.

When the doors opened at last, he walked stiff legged out of the cage.

Though he was still a thousand kilometers above the Earth, and his new-found weight was entirely artificial, he felt that he was already in the cruel grip of the planet below. if he could not pass the test, he would be shipped back to Titan in disgrace.

It was true that those who just failed to make the grade could take a highspeed toughening-up course, primarily intended for returning Lunar residents. This, however, was safe only for those who had spent most

of their infancy on Earth, and Duncan could not possibly qualify. He forgot all these fears when he entered the lounge and saw the cresent

Earth, filling half the sky and slowly sliding along the huge observation windows-themselves a famous tour de * force of space engineering. Duncan had no intention of calculating how many tons of air pressure they were resisting; as he walked, up to the nearest, it was easy to imagine that there was nothing protecting him from the vacuum of space. The sensation was both exhilarating and disturbing.

He had intended to go through the check list that the doctor had given him, but that awesome view made it impossible. He stood rooted to the spot, only shifting his unaccustomed weight from one foot to the other as hitherto unknown muscles registered their complaints.

Port Van Allen circled the globe every two hours, and also rotated on its own axis three times a minute. After a while, Duncan found that he could ignore the station’s own spin; his mind was able to cancel it out, like an irrelevant background noise or a persistent but neutral odor. Once he had achieved this mental attitude, he could imagine that he was alone in space, a human satellite racing along the Equator from night into day. For the

Earth was waxing visibly even as he watched, the curved line of dawn moving steadily away from him as he hurtled into the east.

As usual, there was little land visible, and what could be seen through or between the clouds seemed to have no relationship to any maps. And from this altitude there was not the slightest sign of life-still less of intelligence. it was very hard to believe that most of human history had taken place beneath that blanket of brilliant white, and that, until a mere three hundred years ago, no man had ever risen above it.

He was still searching for signs of life when the disc started to contrast to a crescent once more, and the public-address system called on all passengers for Earth to report to the shuttle embarkation area, Elevators

Two and Three.

He just had time to stop at the “Last Chance” toilet-almost as famous

as the lounge windows-and then he was down by elevator again, back into the weightless world of the station’s hub, where the Earth-to-orbit shuttle was being readied for its return journey.

There were no windows here, but each passenger had his own vision screen, on the back of the seat in front of hina, and could switch to forward, rear, or downward as preferred. The choice was not completely free, though this fact was not widely advertised. Images that were likely to be too disturbing like the final moments of docking or touchdown were thoughtfully censored by the ship’s computer.

It was pleasant to be weightless again-if only during the fifty minutes needed for the fall down to the edge of the atmosphere-and to watch the

Earth slowly changing from a planet to a world. The curve of the horizon became flatter and flatter; there were fleeting glimpses of islands and the spiral nebula of a great storm, raging in silence far below. Then at last a feature that Duncan could recognize-the characteristic narrow isthmus of the California coastline, as the shuttle dropped out of the Pacific skies for its final landfall, still the width of a continent away.

He felt himself sinking deeper and deeper into the superbly padded seat, which spread the load so evenly over his body that there was the minimum of discomfort. But it was hard to breathe, until he remembered the “Advice to

Passengers” he had finally managed to read. Don’t try to inhale deeply, it had said; take short, sharp pants, to reduce the strain on the chest muscles. He tried it, and it worked.

Now there was a gentle buffeting and a distant roar, and the vision screen flashed into momentary flame, then switched automatically from the fires of reentry to the view astern. The canyons and deserts dwindled behind, to be replaced by a group of lakes-obviously artificial, with the tiny white flecks of sailboats clearly visible. He caught a glimpse of the huge

V-shaped wake, kilometers long, of some vessel going at great speed over the water, although from this altitude it seemed completely motionless.

Then the scene changed with an abruptness that took him by surprise.

He might have been flying over the ocean once more, so uniform was the view below. Still so high that he could not see the individual trees, he was passing over the endless forests of the American Midwest.

Here indeed was proof of Life, on a scale such as he had never imagined. On all of Titan, there were fewer than a hundred trees, cherished and protected with loving care. Spread out beneath him now were incomputable millions.

Somewhere, Duncan had encountered the phrase “primeval forest,” and now it flashed again into his mind. So must the Earth have looked in the ancient days, before Man had set to work upon it with fire and axe. Now, with the ending of the brief Agricultural Age, much of the planet was reverting to something like its original state.

Though the fact was very hard to believe, Duncan knew perfectly well that the “primeval forest” lying endlessly beneath him was not much older than

Grandfather. Only two centuries ago, this had all been farmland, divided into enormous checkerboards and covered in the autumn with golden grain. (That concept of seasons was another local reality he found extremely difficult to grasp…. ) There were still plenty of farms in the world, run by eccentric hobbyists or biological research organizations, but the disasters of the twentieth century had taught men never again to rely on a technology that, at its very best, had an efficiency of barely one percent.

The sun was sinking, driven down into the west with unnatural speed by the shuttle’s velocity. It clung to the horizon for a few seconds, then winked out. For perhaps a minute longer the forest was still visible; then it faded into obscurity.

But not into darkness. As if by magic, faint lines of light had appeared on the land below-spiders’ webs of luminosity, stretching as far as the eye could see. Sometimes three or four lines would meet at a single glowing knot. There were also isolated islands of phosphorescence, apparently unconnected with the main network. Here was further proof of Man’s existence; that great forest was a much