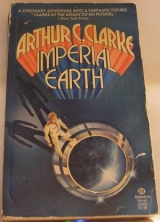

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Seating. He wondered how many starving passengers were now converging upon the Chief Steward, in search of an earlier time slot.

Enioyin!~ the sensation of man-made weight which, barrina accidents, would remain constant until the moment of mid-voyage, Duncan went to join the rapidly lengthening line at the cafeteria.

Already, his first thirty years of life on Titan seemed to belong to

another existence.

LAST WORDS

For onemomentmore, the achingly familiar image remained frozen on the screen. Behind Marissa and the children, Duncan could see the two armchairs of the living room, the photograph of Grandfather (as usual, slightly askew), the cover of the food distribution hatch, the door to the main bedroom, the bookcase with the few but priceless treasures that had survived two centuries of interplanetary wandering…. This was his universe. It held everything he loved, and now he was leaving it.

Already, it lay in his past

It lay only three seconds away, yet that was enough. He had traveled a mere million kilometers in less than half a day; but the sense of separation was already almost complete. It was intolerable to wait six seconds for every reaction and every answer. By the time a reply came, he had forgotten the original question and had started to say something else. And so the attempted conversation had quickly degenerated into a series of stops and starts, while he and Marissa had stared at each other in dumb misery, each waiting for the other to speak…. He was glad that the ordeal was over.

The experience brought home to him, as nothing else had yet done, the sheer immensity of space. The Solar System, he began to suspect, was not designed for the convenience of Man, and that presumptuous creature’s attempts to use it for his own advantage would often be foiled by laws beyond his control. All his life, Duncan had assumed without question that he could speak to friends or family instantly, wherever he might be. Yet now-before he had even passed Saturn’s outer

moons!-that power had been taken from him. For the next twenty days, he would share a lonely, isolated bubble of humanity, able to interact with his fellow passengers, but cut off from all real contact with the rest of mankind.

His self-pity lasted only a few moments. There was also an exhilaration—even a freedom-in this sense of isolation, and in the knowledge that he was setting forth on one of the longest and swiftest voyages that any man could make. Travel to the outer planets was routine and uneventful-but it was also rare, and only a very small fraction of the human race would ever experience it. Duncan remembered a favorite Terran phrase of Malcolm’s, usually employed in a different context, but sound advice for every occasion: “When it’s inevitable, relax and enjoy it.” He would do his best to enjoy this voyage.

Yet Duncan was exhausted when he finally climbed into his bunk at the end of his first day in space. The strain of innumerable farewells, not only to his family but to countless friends, had left him emotionally drained. On top of this, there were all the nagging worries of departure: What had he forgotten to do? What vital necessities had he failed to pack? Had all his baggage been safely loaded and stowed? What essential good-byes had he overlooked? It was useless worrying about these matters now that he was speeding away from home at a velocity increasing by twenty-five thousand kilometers an hour, every hour, yet he could not help doing so. Tired though he was, his hyperactive brain would not let him sleep.

It takes real genius to make a bed that can be uncomfortable at a fifth of a gravity, and luckily the designers of Sirius had not accepted this challenging assignment. After thirty minutes or so, Duncan began to relax and to get his racing thoughts in order. He prided himself on being able to sleep without artificial aids, and it looked as if he would be able to dispense with electro narcosis after all. That was, of course, supposed to be completely harmless, but he never felt pronerly awake the next day.

You’re’falling asleep, he told himself. You won’t know anything more until it’s time for breakfast. All your dreams are going to be happy

ones…. A sound like a small volcano clearing its throat undid the good work of the last ten minutes. He was instantly wide awake, wondering what disaster had befallen Sirius. Not until several anxious seconds had passed did he realize that some antisocial shipmate had found it necessary to visit the adjacent toilet.

Cursing, he tried to recapture the broken mood and to return to the threshold of sleep. But it was useless; the myriad voices of the ship had started to clamor for his attention. He seemed to have lost control of the analytical portion of his brain, and it was busy classifying all the noises from the surrounding universe.

It had been hours since he had really noticed the far-off, ghostly whistling of the drive. Every second Sirius was ejecting a hundred grams of hydrogen at a third of the velocity of light-a trifling loss of mass, yet it represented meaningless millions of gigawatts. During the first few centuries of the Industrial Revolution, all the factories of Earth could not have matched the power that was now driving him sunward.

That incongruously faint and feeble scream was not really disturbing, but it was overlaid with all. sorts of other peculiar sounds. What could possibly cause the “Buzz… click, click … buzz,” the soft “thump … thump … thump,” the “gurgle, hissssss,” and the intermittent “whee-wheee-whee” which was the most maddening of all?

Duncan rolled over and tried to bury. his head in the pillows. It made no difference, except that the higher-pitched sounds got filtered out and the lower frequencies were enhanced. He also became more aware of the steady pulsation of the bed itself, at just about the ten cycles per second nicely calculated to produce epileptic fits.

Hello, that was something new. It was a kind of dispirited kerplunk, kerplunk, kerplunk” that might have been produced by an ancient internal combustion engine in the last stages of decrepitude. Somehow, Duncan seriously doubted that i.c. engines, old or new, were to be found aboard

Sirius. He rolled over on the other side-and then became conscious of the slightly cold airstream from the ventilator hitting him on his left cheek. Perhaps if he ignored it, the sensation would sink below the threshold of consciousness. However, the very effort of pretending it wasn’t there focused attention upon the annoyance.

On the other side of the thin partition, the ship’s plumbing once again advertised its presence with a series of soft thumps. There was an air bubble somewhere in the system, and Duncan knew, with a deadly certainty, that all the engineering skills aboard Sirius would be unable to exorcise it before the end of the voyage.

And what was that? It was a rasping, whistling sound, so irregular that no well-adjusted mechanism could possibly have produced it. As Duncan lay in the darkness, racking his brains to think of an explanation, his annoyance slowly grew to alarm. Should he call the steward and report that something had gone wrong?

He was still trying to make up his mind when a sudden explosive change in pitch and intensity left him in no doubt as to the sound’s origin. Groaning and cursing his luck, Duncan resigned himself to a sleepless night.

Dr. Chung snored..

Someone was gently shaking him. He mumbled “Go away,” then swam groggily upward from the depths of slumber.

“If you don’t hurry,” said Dr. Chung, “you’re going to miss

breakfast.”

THE LONGEST VOYAGE

1 Tis is the Captain speaking. We will be performing a final out-of-ecliptic velocity trim during the next fifteen minutes. This will be your last opportunity for a good view of Saturn, and we are orientating the ship so that it will be visible through the B Lounge windows. Thank you.”

Thank you, thought Duncan, though he was a little less grateful when he reached B Lounge. This time, too many other passengers had been tipped off by the stewards. Nevertheless, he managed to obtain a good vantage point, even though he had to stand.

Though the journey had scarcely begun, Saturn already seemed far away. The planet had dwindled to a quarter of its accustomed size; it was now only twice as large as the Moon would appear from Earth.

Yet though it had shrunk in size, it had gained in impressiveness. Sirius had risen several degrees out of the planet’s equatorial plane, and now at last he could see the rings in all their glory. Thin, concentric silver haloes, they looked so artificial that it was almost impossible to believe that they were not the work of some cosmic craftsman whose raw materials were worlds. Although at first sight they appeared to be solid, when he looked more carefully Duncan could see the planet glimmering through them, its

Ilow light contrasting strangely with their immacuaet’e, snowy whiteness. A hundred thousand kilometers below, the shadow of the rings lay in a dusky band along the equator; it could easily have been taken for an unusually dark cloud belt, rather than something whose cause lay far out in space.

The two main divisions of the rings were apparent at the most casual glance, but a more careful inspection revealed at least a dozen fainter

boundaries where there were abrupt changes in brightness between adjacent sections. Ever since the rings had been discovered, back in the seventeenth century, mathematicians like Dr. Chung had been trying to account for their structure. It had long been known that the attractions of

Saturn’s many moons segregated the billions of orbiting particles into separate bands, but the details, of the process were still unclear.

There was also a certain amount of variation within the individual bands themselves. The outermost ring, for example, showed a distinct mottling or beadiness, and a tiny clot of light was clearly visible near its eastern extremity. Was this, Duncan wondered, a moon about to be born-or the last remnants of one that had been destroyed?

Rather diffidently, he put the question to Dr. Chung.

“Both possibilities have been considered,” she said. “My studies indicate the former. That condensation may, with luck, become another satellite in a few thousand years.”

“I can’t agree, Doctor,” interjected another passenger. “It’s merely a statistical fluctuation in the particle density. They’re quite common, and seldom last more than a few years.”

“The smaller ones-yes. But this is too intense, and too near the edge of the B-ting.”

“But Vanderplas’ analysis of the Janus problem … At that moment, it became rather like the shootout in an old time Western movie. The two scientists reached simultaneously for their hip computers and then retreated, muttering equations, to the back of the lounge.

Thereafter, they completely ignored the real Saturn they had come so far to study-and which, in all probability, they would never see again.

“Captain speaking. We have concluded our velocity trim and are re orientating the ship into the plane of the ecliptic. I hope you had a good view-Saturn will be a long way off next time you see it.”

There was no perceptible sense of motion, but the great ringed globe began to creep slowly down the observation window. The passengers in

front craned forward to follow it, and there was a chorus of disappointed “Ohs” as it finally sank from view below the wide skirting that surrounded the lower part of the ship. That band of metal had one purpose only-to block any radiation from the jet that might stray forward. Even a momentary glimpse of that intolerable glare, bright as a -supernova at the moment of detonation, could cause total blindness; a few seconds’ exposure would be lethal.

Sirius was now aimed almost directly at the sun, as she accelerated toward the inner planets. While the drive was on, there could be no rear-viewing.

Duncan knew that when he next saw Saturn with his unaided eyes, it would be merely a not-very-distinguished star.

A day later, moving at three hundred kilometers a second, the ship passed another milestone. She had, of course, escaped from the planet’s gravitational field hours earlier; neither Saturn-nor, for that matter, the

Sun-could ever recapture her. The frontier that Sirius was crossing now was a purely arbitrary one: the orbit of the outermost moon.

Mnemosyne, only fifteen kilometers in diameter, could claim two modest records. It had the longest period of any satellite, taking no fewer than 1,139 days to orbit Saturn, at an average distance of twenty-one million kilometers. And it also had the longest day of any body in the Solar

System, its period of rotation being an amazing 1,143 days. Although it seemed obvious that these two facts must be connected, no one had been able to arrive at any plausible explanation of Mnemosyne’s sluggish behavior.

Purely by chance, Sirius passed within fewer than a million kilometers of the tiny world. At first, even under the highest power of the ship’s telescope, Mnemosyne was only a minute crescent showing no visible features at all, but as it swiftly grew to a half-moon, patches of light and shade merged which eventually resolved themselves into craters. It was typical of all the denser, Mercury-type satellites-as

opposed to the inner snowballs like Mimas, Enceladus, and Tethys-but to Duncan it now held a special interest. It was more to him than the last landmark on the road to Earth.

Karl was there, and had been for many weeks, with the joint Titan-Terran

Outer Satellite Survey. Indeed, that survey had been in progress as long as

Duncan could remember-the surface area of all the moons added up to a surprising number of million square kilometers-and the TTOSS team was doing a thorough job. There had been complaints about the cost, and the critics had subsided only when promised that the survey would be so thorough that it would never be necessary to go back to the outer moons again. Somehow,

Duncan doubted that the promise would be kept.

He watched the pale crescent of Mnemosyne wax to full, simultaneously dwindling astern as the ship dropped sunward, and wondered fleetingly if he should send Karl a farewell greeting. But if he did, it would only be interpreted as a taunt.

It took Duncan several days to adjust to the complicated schedule of shipboard life-a schedule dominated by the fact that the dining room (as the lounge adjacent to the cafeteria was grandly called) could seat only one third of the passengers at a time. There were consequently three sittings for each of the three main meals-so for nine hours of every day, at least a hundred people were eating, while two hundred were either thinking about the next meal or grumbling about the last. This made it very difficult for the Purser, who doubled as Entertainment Officer, to organize any shipboard activities. The fact that most of the passengers had no wish to be organized did not help him.

Nevertheless, the day was loosely structured by a series of events, at which a good attendance was guaranteed by sheer boredom. There would be a thirty minute newscast from Earth at 0800, with a repeat at 1000, and updates in the evening at 1900 and 2100. At the beginning of the

voyage, the Earth news would be at least an hour and a half late, but it would become more and more timely as Sirius approached her destination.

When she reached her final parking orbit, a thousand kilometers above the

Equator, the delay would be effectively zero, and watches could at last be set by the radio time signals. Those passengers who did not realize this were liable to get into a hopeless state of confusion and, even worse, to miss meal sittings.

All types of visual display, including the contents of several million volumes of fiction and nonfiction, as well as most of the musical treasures of mankind, were available in the tiny library; at a squeeze, it could hold ten people. However, there were two movie screenings every evening in the main lounge, selection being made-if the Purser could be believed -in the approved democratic manner by public ballot. Almost all the great film classics were available, right back to the beginning of the twentieth century. For the first time in his life, Duncan saw Charlie Chaplin’s

Modern Times, much of the Disney canon, Olivier’s Hamlet, Ray’s Pather

Panchali, Kubrick’s Napoleon Bonaparte, Zymanowski’s Moby Dick, and many other old masterpieces that had not even been names to him. But by far the greatest popular success was If This Is Tuesday, This Must Be Mars-a selection from the countless space-travel movies made in the days before space Right was actually achieved. This invariably reduced the audience to helpless hysterics, and it was hard to believe that it had once been banned for in-flight screening because some unimaginative bureaucrat feared that its disasters such as accidentally arriving at the wrong planet might alarm nervous passengers. In fact, it had just the opposite effect; they laughed too much to worry.

The big event of the day, however, was the lottery on the ship’s run, a simple but ingenious device for redistributing wealth among the passengers.

All that one had to do was to guess how far Sirius had traveled along her heliocentric trajectory during the previous twenty-four hours; any number of guesses was permitted, at the cost of one solar each.

At noon, the Captain announced the correct result. The suspense was terrific, as he read out the figures very slowly: “Today’s run has been two-two-seven five-nine -zero -six four-point-three kilometers.” (Cheers and moans.) Since everyone knew the ship’s position and acceleration, it required very little mathematics to calculate the first four or five figures, but beyond that the digits were completely arbitrary, so winning was a matter of luck. Although it was rumored that navigating officers had been bribed to trim the last few decimal places by minute adjustments to the thrust, no one had ever been able to prove it.

Another wealth-distributor was a noisy entertainment called “Bingo,” apparently the main surviving relic of a once flourishing religious order.

Duncan attended one session, then decided that there were better ways of wasting time. Yet a surprising percentage of his very talented and intellectually superior companions seemed to enjoy this rather mindless ritual, jumping up and down and shrieking like small children when their numbers were called…. They could not be criticized for this; they needed some such relaxation.

For they were the loneliest people in the Solar System; hundreds of millions of kilometers separated them from the rest of mankind. Everybody knew this, but no one ever mentioned it. Yet it would not have taken an astute psychologist to detect countless slightly unusual reactions-even minor symptoms of stress-in the behavior of Sirius’ passengers and crew.

There was, for example, a tendency to laugh at the feeblest of jokes, and to go into positive convulsions over catch phrases such as “This is the

Captain speaking” or “Dining room closes in fifteen minutes.” Most popular of all-at least among the men-was “Any more for Cabin 44.” Why the two middle-aged and rather quiet lady geologists who occupied this cabin had acquired a reputation for ravening insatiability was a mystery that Duncan never solved.

Nor was he particularly interested; his heart still ached for Marissa and he would not seek any other consolation until he reached Earth.

Moreover, with 76 the somewhat excessive conscientiousness that was typical of the Makenzies, he was already hard at work by the second day of the voyage.

He had three major projects-one physical and two intellectual. The first, carried out under the hard, cold eye of the ship’s doctor, was to get himself fit for life at one gravity. The second was to learn all that he could about his new home, so that he would not appear too much of a country cousin when he arrived. And the third was to prepare his speech of thanks, or at least to write a fairly detailed outline, which could be revised as necessary during the course of his stay.

The toughening-up process involved a fifteen-minute session, twice a day, in the ship’s centrifuge or on the “race track.” Nobody enjoyed the centrifuge; not even the best background music could alleviate the boredom of being whirled around in a tiny cabin until legs and arms appeared to be made of lead. But the race track was so much fun that it operated right around the clock, and some enthusiasts even tried to get extra time on it.

Part of its appeal was undoubtedly due to sheer novelty; who would have expected to find bicycles in space? The track was a narrow tunnel, with steeply banked floor, completely encircling the ship, and rather like an old-time particle accelerator-except that in this case the particles themselves provided the acceleration.

Every evening, just before going to bed, Duncan would enter the tunnel, climb onto one of the four bicycles, and start pedaling slowly around the sixty meters of track. His first revolution would take a leisurely half minute; then he would gradually work up to full speed. As he did so, he would rise higher and higher up the baAed wall, until at maximum speed he was almost at right angles to the floor. At the same time, he would feel his weight steadily increase; the bicycle’s speedometer had been calibrated to read in fractions of a gee, so he could tell exactly how well he was doing. Forty kilometers an hour ten times around

Sirius every minute-was the equivalent of one Earth gravity. After several days of practice Duncan was able to maintain this for ten minutes without too much effort. By the end of the voyage, he could tolerate it indefinitely-as he would have to, when he reached Earth.

The race track was at its most exciting when it contained two or more riders-especially when they were moving at different speeds. Though overtaking was strictly forbidden, it was an irresistible challenge, and on this voyage there were no serious casualties. One of Duncan’s most vivid and incongruous memories of Sirius would be the tinkle of bicycle bells, echoing round and round a brightly lit circular tunnel whose blurred walls flashed by only a few centimeters away…. And the race track also provided him with a more material souvenir, a pseudo medieval scroll which announced to all who were interested that

1, DUNCAN MAKENZIE, OF OASIS

CITY, TITAN, AM HEREBY CERTIFIED TO HAVE BICYCLED FROM SATURN TO EARTH,

AT

AN AVERAGE VELOCITY OF 2,176,420 KILOMETERS AN HOUR.

Duncan’s mental preparation for life on Earth occupied considerably more time, but was not quite so exhausting. He already had a good knowledge of

Terran history, geography, and current affairs, but until now it had been mostly theoretical, because it had little direct application to him. Both astronomically and psychologically, Earth had been a long way off. Now it was coming closer by millions of kilometers a day.

Even more to the point, he was now surrounded by Terrans; there were only seven passengers from Titan aboard Sirius, so they were outnumbered fifty to one. Whether he liked it or not, Duncan was being rapidly brainwashed and molded by another culture. He found himself using Terran figures of speech, adopting the slightly sing-song intonation now universal on Earth, and employing more and more words of Chinese origin. All this was to be expected; what he found disturbing was the fact that his own swiftly receding world was becoming steadily

more unreal. Before the voyage was finished, he suspected that he would have become half-Terran.

He spent much of his time viewing Earth scenes, listening to famous political debates, and trying to understand what was happening in culture and the arts, so that he would not appear to be a complete barbarian from the outer darkness. When he was not sitting at the viddy, he was likely to be flicking through the pages of a small, dense booklet optimistically entitled Earth in Ten Days. He was fond of trying out bits of new-found information on his fellow passengers, to study their reactions and to check on his own understanding. Sometimes the response was a blank stare, sometimes a slightly condescending smile. But everyone was very polite to him; after a while, Duncan realized that there was some truth in the old cliche that Terrans were never unintentionally rude.

Of course, it was absurd to apply a single label to half a billion people-or even to the three hundred and fifty on the ship. Yet Duncan was surprised to find how often his preconceived ideas-even his prejudices-were perfectly accurate. Most Terrans did have a quite unconscious air of superiority. At first, Duncan found it annoying; then he realized that several thousand years of history and culture justified a certain pride.

It was still too early for him to answer the question, so long debated on all the other worlds: “Is Earth becoming decadent?” The individuals he had met aboard Sirius showed no trace of that effete over sensibility with which

Terrans were frequently charged-but, of course, they were not a fair sample. Anyone who had occasion to visit the outer reaches of the Solar

System must possess exceptional ability or resources.

He would have to wait until he reached earth before he could measure its decadence more precisely. The project might be an interesting

one-if his budget and his timetable could stand the strain.

SONGS OF EMPIRE

In a hundred years, thought Duncan, he could never have managed to arrange this deliberately. Masterful administration of the unforeseen, indeed! Colin would be proud of him…. It had all begun quite accidentally. When he discovered that the Chief

Engineer bore the scarcely uncommon name of Mackenzie, it had been natural enough to introduce himself and to compare family trees. A glance was sufficient to show that any relationship was remote: Warren Mackenzie,

Doctor of Astrotechnology (Propulsion) was a freckled redhead.

It made no difference, for he was pleased to meet Duncan and happy to chat with him. A genuine friendship had developed, long before Duncan decided to take advantage of it.

“I sometimes feel,” Warren lamented, not very seriously, “that I’m a living cliche. Did you know that there was a time when all ship’s engineers were

Scots, and called Mac-something-or-other?”

“I didn’t know it. Why not Germans or Russians? They started the whole thing.”

“You’re on the wrong wavelength. I’m talking about ships that float on water. The first powered ones were driven by steam-piston engines, working paddle wheels-around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Now, the

Industrial Revolution started in Britain, and the first practical steam engine was made by a Scot. So when steamships began to operate all over the world, the Macs went with them. No one else could understand

such complicated pieces of machinit cry. “Steam engines? Complicated? You must be joking. 99

“Have you ever looked at one? More to it than you might think, though it doesn’t take long to figure it out…. Anyway, while the steamships lasted-that was only about a hundred years-the Scots ran them. I’ve made a hobby of the period; it has some surprising parallels with our time.”

“Go on-surprise me.”

“Well, those old ships were incredibly slow, averaging only about ten klicks, at least for freighters. So really long journeys, even on Earth, could take weeks. Just like space travel.”

“I see. In those days, the countries on Earth were almost as far apart as the planets.”

“Well, some of them. The most perfect analogy is the old British

Commonwealth, the first and last world empire. For almost a hundred years, countries like Canada, India, and Australia relied entirely on steamships to link them to Britain; the one-way journey could easily take a month or more, and was often a once-in-a-lifetime affair. Only the wealthy, or people on official business, could afford it. And-just like today-people in the colonies couldn’t even speak to the mother country. The psychological isolation was almost complete.”

“They had telephones, didn’t they?”

“Only for local use, and only a few even then. I’m talking about the beginning of the twentieth century, remember. Universal global communication didn’t arrive until the end of it.”

“I feel that the analogy is a little forced,” protested Duncan. He was intrigued but unconvinced, and quite willing to listen to Mackenzie’s arguments-as yet, with no ulterior motive.

“I can give you some more evidence that makes a better case. Have you heard of Rudyard Kipling?”

“Yes, though I’ve never read anything of his. He was a writer, wasn’t he?

Anglo-American-sometime between Melville and Hemingway. English Lit’s almost unknown territory to me. Life’s too short.”

“True, alas. But I have read Kipling. He was the first poet of the

machine age, and some people think he was also the finest short-story writer of his century. I couldn’t judge that, of course, but he exactly described the period I’m talking about. “McAndrew’s Hymn,” for example-an old engineer musing about the pistons and boilers and crankshafts that drive his ship round the world. Its technology-not to mention its theology!-has been extinct for three hundred years; but the spirit behind it is still as valid as ever.

“And he wrote poems and stories about the far places of the empire which make them seem quite as remote as the planets are today-and sometimes even more exotic! There’s a favorite of mine called “The Song of the Cities.” I don’t understand half the allusions, but the tributes to Bombay, Singapore,

Rangoon, Sydney, Auckland… make me think of Luna, Mercury, Mars,

Titan…”

Mackenzie paused and looked just a little embarrassed.

“I’ve tried to do something of the same kind myself-but don’t worry, I won’t inflict my verses on it you.

Duncan made the encouraging noises he knew were expected. He was quite sure that before the end of the voyage he would be asked for his criticism-translation, praise—of Mackenzie’s literary efforts.