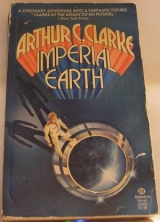

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Duncan turned to the guide who had driven him through the labyrinth of access tunnels on. the small, chemically powered scooter. “I don’t see anyone,” he complained. “Are you sure he’s here?”

“This is where we left him, an hour ago. He’ll be in the preamplifier

assembly, up there on the platform. 242 You’ll have to shout-no radios allowed here, of course.”

Duncan could not help smiling at this further example of the CYCLOPS management’s almost fanatical precautions against interference. He had even been asked to surrender his watch, lest its feeble electronic pulses be mistaken for signals from an alien civilization a few hundred light-years away. His guide was actually wearing a spring-driven timepiece-the first that Duncan had ever seen.

Cupping his hands around his mouth, Duncan tilted his head toward the metal tower looming above him and shouted “Karl!” A fraction of a second later, the K echoed back from the next antenna, then reverberated feebly from the ones beyond. After that the silence seemed more profound than before. Duncan did not feel like disturbing it again.

Nor was there any need. Fifty meters above, a figure had moved to the railing around the platform; and it brought with it the familiar glint of gold.

“V~Io’s there?”

Who do you think? Duncan asked himself. Of course, it was hard to recognize a person from vertically overhead, and voices were distorted in this inhumanly scaled place.

“It’s Duncan.”

There was a pause that seemed to last for the better part of a minute, but could only have been a few seconds in actuality. Karl was obviously surprised, though by this time he must surely have guessed that Duncan knew of his presence on Earth. Then he answered: “I’m in the middle of a job.

Come up, if you want to.”

That was hardly a welcome, but the voice did not seem hostile. The only emotion that Duncan could identify at this distance was a kind of tired resignation; and perhaps he was imagining even this.

Karl had vanished again, doubtless to continue whatever task he had come here to perform. Duncan looked very thoughtfully at the spiral stairway winding up the cylindrical trunk of the antenna tower.

Fifty meters was a trifling distance-but not in terms of Earth’s gravity It was the equivalent of two him243 dred and fifty on Titan; he had never had to climb a quarter of a kilometer on his own world.

Karl, of course, would have had little difficulty, since he had spent his early years on Earth, and his muscles would have recovered much of their original strength. Duncan wondered if this was a deliberate challenge. That would be typical of Karl, and if so he had no choice in the matter.

As he stepped onto the first of the perforated metal stairs, his CYCLOPS guide remarked hopefully: “There’s not much room up there on the platform.

Unless you want me, I’ll stay here.”

Duncan could recognize a lazy man when he met one, but he was glad to accept the excuse. He did not wish any strangers to be present when he came face to face with Karl. The confrontation was one that he would have avoided if it had been at all possible, but this was not a job that could be delegated to anyone else-even if those instructions from Colin and

Malcolm had allowed it.

The climb was easy enough, though the safety rail was not as substantial as

Duncan would have wished. Moreover, sections had been badly rusted, and now that he was close enough to touch the metal he could see that the mounting was in even worse condition than he had been led to expect. Unless emergency repairs were carried out very soon, CYCLOPS would never see the dawn of the twenty-fourth century.

When Duncan had completed his first circuit, the guide called up to him: “I forgot to tell you-we’re selecting a new target in about five minutes.

You’ll find it rather dramatic.”

Duncan stared up at the huge bowl now completely blocking the sky above him. The thought of all those tons of metal swinging around just overhead was quite disturbing, and he was glad that he had been warned in time.

The other saw his action and interpreted it correctly.

“It won’t bother you. This antenna’s been frozen for at least ten years.

The drive’s seized up, and not worth repairing.” So that confirmed a suspicion of Duncan’s, which he had dismissed as an optical illusion. The great parabola above him was indeed at a slight angle to all the others; it was no longer an active part of the CYCLOPs array, but was now pointing blindly at the sky. The loss of one-or even a dozen–elements would cause only a slight degradation of the system.” but it was typical of the general air of neglect. One more circuit, and he would be at the platform. Duncan paused for breath. He had been climbing very slowly, but already his legs were beginning to ache with the wholly unaccustomed effort. There had been no further * sound from Karl. What was he doing, in this fantastic place of old triumphs and lost dreams?

And how would he react to this unexpected, and doubtless unwelcome, confrontation, when they were face to face? A little belatedly, it occurred to Duncan that a small platform fifty meters above the ground, and in this frightful gravity, was not the best place to have an argument. He smiled at the mental image this conjured up; whatever their disagreement, violence was unthinkable.

Well, not quite unthinkable. He had just thought of it…. Overhead now was a narrow band of perforated metal flooring, barely wide enough for the rectangular slot through which the stairway emerged. With a heartfelt sigh of relief, pulling himself upward with rust-stained hands,

Duncan climbed the last few steps and stood amid monstrous bearings, silent hydraulic motors, a maze of cables, much dismantled plumbing, and the delicate tracery of ribs supporting the now useless hundred-meter parabola.

There was still no sign of Karl, and Duncan began a cautious circumnavigation of the antenna mounting. The catwalk was about two meters wide, and the protective rail almost waist-high, so there was no real danger. Nevertheless, he kept well away from the edge and avoided looking at the fifty-meter drop.

He had barely completed half a circuit when all hell broke loose. There

was a sudden whirr of motors, the low booming of great machineries on the move—and even the occasional accompaniment of protesting shrieks from gears and bearings that did not wish to be disturbed.

On every side, the huge skyward-facing bowls were beginning to tam in unison, swinging around to the south. Only the one immediately overhead was motionless, like a blind eye no longer able to react to any stimulus. The din was quite astonishing, and continued for several minutes. Then it stopped as abruptly as it had started. CYCLOPs had located a new target for its scrutiny.

“Hello, Duncan,” said Karl in the sudden silence. “Welcome to Earth.”

He had emerged, while Duncan was distracted by the tumult, from a small cubicle on the underside of the parabola, and was now climbing down a somewhat precarious arrangement of hanging ladders. His descent looked particularly hazardous because he was using only one hand; the other was firmly clutching a large notebook, and Duncan did not relax until Karl was safely on the platform, a few meters away. He made no attempt to come closer, but stood looking at Duncan with a completely unfathomable expression, neither friendly nor hostile.

Then there was one of those embarrassing pauses when neither party wishes to speak first, and as it dragged on interminably Duncan became aware for the first time of an omnipresent faint hum from all around him. The cycLops array was alive now, its hundreds of tracking motors working in precise synchronism. There was no perceptible movement of the great antenna’s, but they would now be creeping around at a fraction of a centimeter a second.

The multiple facets of the CYCLOPs eye, having fixed their gaze upon the stars, were now turning at the precise rate needed to counter the rotation of the Earth.

How foolish, in this awesome shrine dedicated to the cosmos itself, for two grown men to behave like children, each trying to outface the other! Duncan had the dual advantage of surprise and a clear conscience; he would have nothing to lose by speaking first. He did

not wish to take the initiative and perhaps antagonize Karl, so it was best to open with some innocuous triviality.

No, not the weather-the amount of Terran conversation devoted to that was quite incrediblel-but something equally neutral.

“That was the hardest work I’ve done since I got here. I can’t believe that people really~ climb mountains on this planet.”

Karl examined this brilliant gambit for possible booby traps. Then he shrugged his shoulders and replied: “Earth’s tallest mountain is two hundred times as high as this. People climb it every year.”

At least the ice was broken, and communication had been established. Duncan permitted himself a sigh of relief; at the same time, now that they were at close quarters, he was shocked by Karl’s appearance. Some of that golden hair had turned to silver, and there was much less of it. In the year since they had last met, Karl seemed to have aged ten. There were crow’s-feet wrinkles of anxiety around his eyes, and his brow was now permanently furrowed. He also seemed to have shrunk considerably, and Earth’s gravity could not be wholly to blame, for Duncan was even more vulnerable to that.

On Titan, he had always had to look up at Karl; now, as they stood face to face, their eyes were level.

But Karl avoided his gaze and moved restlessly back and forth, firmly clutching the notebook he was stiff carrying. Presently he walked to the very edge of the platform and leaned with almost ostentatious recklessness against the protective rail.

“Don’t do that!” protested Duncan. “It makes me nervous.” That, he suspected, was the purpose of the exercise.

“Why should you care?”

The brusque answer saddened Duncan beyond measure. He could only reply: “If you really don’t know, it’s too late for me to explain.”

“Well, I know this isn’t a social visit. I suppose you’ve seen Calindy?”

“Yes. I’ve seen her.” “What are you trying to do?” 247 “I can’t speak for Calindy. She doesnt even know that I’m here.”

“What are the Makenzies trying to do? For the good of Titan, of course.”

Duncan knew better than to argue. He did not even feel angry at the calculated provocation.

“All I’m trying to do is to avoid a scandal-if it’s not too late.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“You know perfectly well. Who authorized your trip to Earth? Who’s paying your expenses?”

Duncan had expected Karl to show some signs of guilt, but he was mistaken.

“I have friends here. And I don’t recall that the Makenzies worried too much about regulations. How did Malcolm get the first Lunar orbital refueling contract?”

“That was a hundred years ago, when he was trying to get the Titan economy started. There’s no excuse now for financial irregularities. Especially for purely personal ends.”

This was, of course, a shot in the dark, but he appeared to have landed on some target. For the first time, Karl looked angry.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” he snapped back. “One day

Titan…”

CYCLOPS gently but firmly interrupted him. They had quite forgotten the slow tracking of the great antennas on every side, and were no longer even aware of the faint whirr of the hundreds of drive motors. Until a few seconds ago, the upper platform of 005 had been shielded by the inverted umbrella of the next bowl, but now its shadow was no longer falling upon them. The artificial eclipse was over, and they were blasted by the tropical sun.

Duncan closed his eyes until his dark glasses had adjusted to the glare.

When he opened them again, he was standing in a world divided sharply into night and day. Everything on one side was clearly visible, while in the shadow only a few centimeters away he could see absolutely nothing. The contrast between light and darkness, exaggerated by his

glasses, was so great that Duncan could almost imagine he was on the airless Moon.

It was also uncomfortably hot, especially for Titanians.

“If you don’t mind,” said Duncan, still determined to be polite, “we’ll move around to the shadow side.” It would be just like Karl to refuse, either out of sheer stubbornness or to demonstrate his superiority. He was not even wearing dark glasses, though he was holding the notebook to shield his eyes.

Rather to Duncan’s surprise, Karl followed him meekly enough around the catwalk, into the welcome shade on the northern face of the tower. The utter banality of the interruption seemed to have put him off his stride.

“I was saying,” continued Duncan, when they had settled down again, “that

I’m merely trying to avoid any unpleasantness that will embarrass both

Earth and Titan. There’s nothing personal in this, and I wish that someone else were doing it-believe me.1P

Karl did not answer at once, but bent down and carefully placed his notebook on the most rust-free section of the catwalk he could find. The action reminded Duncan so vividly of old times that he was absurdly moved.

Karl had never been able to express his emotions properly unless his hands were free, and that notebook was obviously a major hindrance.

“Listen carefully, Duncan,” Karl began. “Whatever Calindy told you-“

“She’s told me nothing.”

“She must have helped you find me.”

“Not even that. She doesn’t even know I’m here.”

“I don’t believe you.”

Duncan shrugged his shoulders and remained silent. His strategy seemed to be working. By hinting that he knew much more than he did-which was indeed little enougb-he hoped to undercut Karl’s confidence and gain further admissions from him. But what he would do then, he still had no idea; he could only rely on Colin’s maxim of the masterful

administration of the unforeseen. Karl had now begun to pace back and forth in such an agitated manner that, for the first time, Duncan felt distinctly nervous. He remembered Calindy’s warning; and once again, he reminded himself uneasily that this was not at all a good place for a confrontation with an adversary who might be slightly unbalanced.

Suddenl ,v, Karl seemed to come to a decision. He stopped his uncertain weaving along the narrow catwalk and turned on his heel so abruptly that Duncan drew back involuntarily. Then he realized, with both surprise and relief, that Karl’s hands were outstretched in a gesture of pleading, not of menace.

“Duncan,” he began, in a voice that was now completely changed. “You can help me. What I’m trying to do—P

It was as if the sun had exploded. Duncan threw his hands before his eyes and clenched them tightly against the intolerable glare. He heard a cry from Karl, and a moment later the other bumped into him violently, rebounding at once.

The actinic detonation had lasted only a fraction of a second. Could it have been lightning? But if so, where was the thunder? It should have come almost instantaneously, for a flash as brilliant as this.

Duncan dared to open his eyes, and found that he could see again, though through a veil of pinkish mist. But Karl, it was obvious, could not see at all; he was blundering around blindly, with his hands cupped tightly over his eyes. And still the expected thunder never came…. If Duncan had not been half-paralyzed by shock, he might yet have acted in time. Everything seemed to happen in slow motion, as in a dream. He could not believe that it was real.

He saw Karl’s foot hit the precious notebook, so that it went spinning off into space, fluttering downward like some strange, white bird. Blinded though he was, Karl must have realized what he had done. Totally disoriented, he made one futile grab at the empty air, then crashed into the guardrail. Duncan tried to reach him, but it was too

late. 250 Even then, it might not have mattered; but the years and the rust had done their work. As the treacherous metal parted, it seemed to Duncan that Karl cried out his name, in the last second of his life. But of that he would never be sure.

THE LISTENERS

“You’re under no legal compulsion,” Ambassador Farrell had explained. “If you wish, I could claim diplomatic immunity for you. But it would be unwise, and might lead to various-ah-difficulties. In any case, this inquiry is in the mutual interest of all concerned. We want to find out what’s happened, just as much as they do.”

“And who are they?”

“Even if I knew, I couldn’t tell you. Let’s say Terran Security.”

“You still have that kind of nonsense here? I thought spies and secret agents went out a couple of hundred years ago.”

“Bureaucracies are self-perpetuating-you should know that. But civilization will always have its discontents, to use a phrase I came across somewhere.

Though the police handles most matters, as they do on Titan, there are cases which require-special treatment. By the way, I’ve been asked to make it clear that anything you care to say will be privileged and won’t be published without your consent. And if you wish, I will come along with you for moral support and guidance.”

Even now, Duncan was not quite sure who the Ambassador was representing, but the offer was a reasonable one and he had accepted it. He could see no harm in such a private meeting; some kind of judicial inquiry was obviously needed, but the less publicity, the better.

He had half expected to be taken in a blacked-out car on a long, tortuous drive to some vast underground complex in the depths of Virginia or Maryland. It was a little disappointing to end up in a small room at the old

State Department Building, talking to an Assistant Under Secretary with the improbable name of John Smith; later checking on Duncan’s part disclosed that this actually was his name. However, it soon became clear that there was much more to this room than the plain desk and three comfortable chairs that met the eye.

Duncan’s suspicions about the large mirror that covered most of one wall were quickly confirmed. His host—or interrogator, if one wanted to be melodramatic-saw the direction of his glance and gave him a candid smile.

“With your permission, Mr. Makenzie, we’d like to record this meeting. And there are several other participants watching; they may join in from time to time. If you don’t mind, I’ll refrain from introducing them

Duncan nodded politely toward the mirror.

“I’ve no objection to recording,” he said. “Do you mind if I also use my

Minisec?”

There was a painful silence, broken only by an ambassadorial chuckle. Then

Mr. Smith answered: “We would prefer to supply you with a transcript. I can promise that it will be quite accurate.”

Duncan did not press the point. Presumably, it might cause embarrassment if some of the voices involved were recognized by outsiders. In any case, a transcript would be perfectly acceptable; he could trust his memory to spot errors or deletions.

“Well, that’s fine,” said Mr. Smith, obviously relieved. “Let’s get started.”

Simultaneously, something odd happened to the room. Its acoustics changed abruptly; it was as if it had suddenly become much larger. There was not the slightest visible alteration, but Duncan had the uncanny feeling of unseen presences all around him. He would never

know if they were actually in Washington or on the far side of the Earth, and it gave him an uncomfortable, naked sensation to be surrounded by invisible listeners-and watchers.

A moment later, a voice spoke quietly from the air immediately in front of him.

“Good morning, Mr. Makenzie. It’s good of you to spare us your time, and please excuse our reticence. If you think this is some kind of twentieth-century spy melodrama, our apologies. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, these precautions are totally unnecessary. But we can never tell which occasion will be the hundredth.”

It was a friendly, powerful voice, very deep and resonant, yet there was something slightly unnatural about it. A computer? Duncan asked himself.

That was too easy an assumption; in any case, there was no way of distinguishing between computer vocalization and human speech-especially now that a realistic number of “ers,” “wells,” incomplete sentences, and downright grammatical errors could be incorporated to make the nonelectronic participants in a conversation feel at ease. He guessed that he was listening to a, man talking through a speech-disguising circuit.

While Duncan was still trying to decide if any answer was necessary, another speaker took over. This time, the voice emerged about half a meter from his left ear.

“It’s only fair to reassure you on one point, Mr. Makenzie. As far as we can ascertain, no Terran laws have been broken. We are not here to investigate a _crime—only to solve a mystery, to explain a tragedy. If any

Titanian regulations are involved, that is your problem-not ours. I hope you understand. ““Yes Duncan replied. “I assumed that was the case, but I’m glad to have your confirmation.”

This was indeed a relief, but he knew better than to relax. Perhaps this statement was exactly what it seemed to be-a friendly plea for cooperation. But it might also be a trap.

Now a woman’s voice came from immediately be hind him, and he had to resist the impulse to swing around and look at the speaker. Was this

quite unnecessary shifting of sound focus a deliberate at tempt to disorient him? How naieve did they take him to be?

“To save us all time, let me explain that we have a complete summary of Mr.

Helmer’s background.” And mine, thought Duncan. “Your government has been most helpful, but you may have information which is unknown to us, since you were one of his closest friends.”

Duncan nodded, without bothering to speak. They would know all about that friendship, and its ending.

As if responding to some hidden signal, Mr. Smith opened his briefcase and carefully laid a small object on the table.

“You’ll recognize this, of course,” the female voice continued. “The Helmer family has asked that it be handed over to you for safe custody, with the other property of the deceased.”

The sight of Karl’s Minisec-virtually the same model as his own-was in itself such a shock that at first the remainder of the message failed to get through. Then Duncan reacted with a start and said: “Would you please repeat that?”

There was such a surprisingly long delay that he wondered if the speaker was on the Moon; during the course of the session, Duncan became almost certain of it. With all the other interrogators, there was a quick give-and-take, but with the lone woman there was always this invariable time-lag.

“The Helmers have asked that you be custodian of their son’s effects, until disposition is settled.”

It was a gesture of peace, across the grave of all their hopes, and Duncan felt his eyes stinging with unshed tears. He looked at the handful of microelectronics on the table and felt a deep reluctance even to touch it.

There were all Karl’s secrets. Would the Helmers have asked him to accept this if they had anything to hide? But there was a great deal, Duncan was certain, that Karl had concealed from his own family; there would be much in the Minisec that only he had ever known. True, it would be guarded by carefully chosen code words, some of them possibly

linked with ERASE circuits to prevent unauthorized intrusion. “Naturally,” continued the voice from the Moon (if it was from the Moon), 66we are interested in what may be in this Minisec. In particular, we would like any list of contacts on Earth-addresses or personal numbers.”

Yes, thought Duncan, I can understand that. I’m sure you must have been tempted to do some interrogation already, but are scared of possible ERASE circuits and want to explore other alternatives first…. He stared thoughtfully at that little box on the table, with its multitudinous studs and its now darkened read-out panel. There lay a device of a complexity beyond all the dreams of earlier ages-a virtual micro simulacrum of a human brain. Within it were billions of bits of information, stored in endless atomic arrays, waiting to be recalled by the right signal—or obliterated by the wrong one. At the rhoment it was lifeless, inert, like consciousness itself in the profoundest depths of sleep. No-not quite inert; the clock and calendar circuits would still be operating, ticking off the seconds and minutes and days that now were no concern of Karl’s.

Another voice broke in, this time from the right.

“We have asked Mr. Armand Helmer if his son left any code words with him, as is usual in such cases. You may be hearing more on the matter shortly.

Meanwhile, no attempt will be made to obtain any read-outs. With your permission, we would like to retain the Minisec for the present.”

Duncan was getting a little tired of having decisions made for him-and the

Helmers had apparently stated that he was to take possession of Karl’s effects. But there was no point in objecting; and if he did, some legal formality would undoubtedly materialize out of the same thin air as these mysterious voices.

Mr. Smith was digging into his case again.

“Now there is a second matter-I’m sure you’ll also recognize this.”

“Yes. Karl usually carried a sketchbook. Is this the one he had with him when-“

“It is. Would you like to go through it, and see if there is anything

that strikes you as unusual-note255 worthy-of any possible value to this investigation? Even if it seems utterly trivial or irrelevant, please don’t hesitate to speak.”

What a technological gulf, thought Duncan, between these two objects! The

Minisec was a triumph of the Neoelectronic Age; the sketchbook had existed virtually unchanged for at least a thousand years -and so had the pencil tucked into it. It was very true, as some philosopher of history had once said, that mankind never completely abandons any of its ancient tools. Yet

Karl’s sketchbooks had always been something of an affectation; he could make competent engineering drawings, but had never shown any genuine sign of artistic talent.

As Duncan slowly turned the leaves, he was acutely conscious of the hidden eyes all around him. Without the slightest doubt, every page here had been carefully recorded, using all the techniques that could bring out invisible marks and erasures. It was hard to believe that he could add much to the investigations that had already been made.

Karl apparently used his sketchbooks to make notes of anything that interested him, to conduct a sort of dialogue with himself, and to express his emotions. There were cryptic words and numbers in small, precise handwriting, fragments of calculations and equations, mathematical sketches

And there were spaces capes obviously rough drawings of scenes on the outer moons, with the formalized circle-and-ellipse of Saturn hanging in the sky . circuit diagrams, with more calculations full of lambdas and omegas, and vector notations that Duncan could recognize, but could not understand . and then suddenly, bursting out of the pages of impersonal notes and rather inept sketches, something that breathed life, something that might have been the work of a real artist-a portrait of Calindy, drawn with obvious, loving care.

It should have been instantly recognizable; yet strangely enough, for a fraction of a second, Duncan stared at it blankly. This was not the

Calindy he now knew, for the real woman was already obliterating the image from the past. Here was Calindy as they had both remembered her-the girl frozen forever in the bubble stero, beyond the reach of Time.

Duncan looked at the picture for long minutes before turning the page. It was really excellent-quite unlike all the other sketches. But then, how many times had Karl drawn it, over and over again, during the intervening years?

No one spoke from the air around him or interrupted his thoughts. And presently he moved on. . more calculations… patterns of hexagons, dwindling away into the distance-why, of course!

“ThaVs the titanite lattice-but the number written against it means nothing to me. It looks Eke a Terran viddy coding.”

“You are correct. It happens to be the number of a gem expert here in

Washington. Not Ivor Mandel’stahm, in case you’re wondering. The person concerned assures us that Mr. Helmer never contacted him, and we believe him. It’s probably a number he acquired somehow, jotted down, but never used.” more calculatiogs, now with lots of frequencies and phase angles.

Doubtless communications stuff part of Karl’s regular work … . geometrical doodles, many of them based on the hexagon motif … Calindy again-only an outline sketch this time, showing none of the loving care of the earlier draw in ! … : a honeycomb pattern of little circles, seen in plan and elevation. Only a few were drawn in detail but it was obvious that there must be hundreds. The interpretation was equally obvious.

“The CYCLops array-yes, he’s written in the number of elements and the overall dimensions.”

“Why do you think he was so interested?”

“That’s quite natural-it’s the biggest and most famous radio telescope on

Earth. He often discussed it with me.”

“Did he ever speak of visiting it?”

“Very likely-but I don’t remember. After all, this was some years ago.”

The drawings on the next few pages, though very rough and diagrammatic, were clearly details of cyCLOPs-antenna feeds, tracking mechanisms, obscure bits of circuitry, interspersed with yet more calculations. One sketch had been started and never finished. Duncan looked at it sadly, then turned the page. As he had expected, the next sheet was blank.

“I’m sorry to disappoint you,” he said, closing the book, “but I get nothing at all from this. Kar-Mr. Helmer’s field was communications science; he helped design the Titan-Inner Planets Link. This is all part of his work. His interest is completely understandable, and I see nothing unusual about it.”

“Perhaps so, Mr. Makenzie. But you haven’t finished.”

Duncan looked in surprise at the empty air. Then Under Secretary Smith gestured toward the sketchbook.

“Never take anything for granted,” he said mildly. “Start at the other end.”