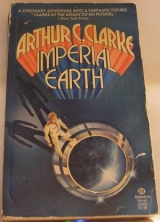

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

“I’m not quite sure. But the moment I saw Calindy, shining like a nova amid all that gloom and chaos down in the old mine workings, I wanted to learn more about her … wanted to make her part of my life. You

know what I mean.” 48 Duncan could only nod his head in silent agreement.

“Sheela didn’t mind-after all, I’m not a babysnatcherl And we both hoped that Calindy would give you someone to think about besides Karl.”

“I was already getting over that, anyway. It was much too frustrating.”

Colin chuckled, not unsympathetically.

“So I can imagine. Karl was spreading himself pretty thin. Half of Titan was in love with him in those days-still is, for that matter. Which is why we must keep him out of politics. Remind me to tell you about Alcibiades someday.”

“Who?”

“Ancient Greek general-too clever and charming for his own good. Or for anyone else’s.”

“I appreciate your concern,” said Duncan, with only a slight trace of sarcasm. “But that increased my problems a hundred percent. As she made quite clear, I was much too young for Calindy, and of course Karl was now interested only in her. And to make matters worse, they didn’t even mind me sharing their bed as long as I didn’t get in the way. In fact—2’

“Yes?”

Duncan’s face darkened. How strange that he had never thought of this before, yet how obvious it wasl

“Didn’t mind, hell! They enjoyed having me there, just to tease me! At least Karl did.”

It should have been a shattering revelation, yet somehow it did not hurt as much as he would have expected. He must have realized for a long time, without admitting it to himself, that there was a very definite streak of cruelty in Karl. Certainly his lovemaking often lacked tenderness and consideration; there were even times when he had scared Duncan into something approaching impotence. And to do that to a virile sixteen-year-old was no mean feat. “I’m glad you’ve realized that,” said Colin somberly. “You had to find it out for yourself-you wouldn’t have believed us. But whatever Karl did, he certainly paid for it. That breakdown was serious. And, frankly, I don’t believe his

recovery is as complete as the doctors claim.” This was also a new thought to Duncan, and he turned it over in his mind.

Karl’s breakdown was still a considerable mystery, which the Helmer family had never discussed with outsiders. The romantics had a simple explanation: he was heartbroken over the loss of Calindy. Duncan had always found this too hard to accept. Karl was too tough to pine away like some character in an old time melodrama–especially when there were at least a thousand volunteers waiting to console him. Yet it was undeniable that the breakdown had occurred only a few weeks after Mentor had, to everyone’s relief, blasted Earthward.

After that, there had been a complete change in his personality; whenever

Duncan met him in these last few years, he had seemed almost a stranger.

Physically, he was as beautiful as ever-perhaps even more so, thanks to his greater maturity. And he could still be friendly, though there were sudden silences when he seemed to retreat into himself for no apparent reason. But real communication was missing; maybe it had never been there…. No, that was unfair and untrue. They had known many shared moments before

Calindy entered their lives. And one, though only one, after she had left.

That was still the deepest pain that Duncan had ever known. He had been inarticulate with grief when they had made their farewells in the shuttle terminus of Meridian, surrounded by scores of other parting guests. To its great surprise, Titan had suddenly discovered that it was going to miss its young visitors; nearly every one of them was surrounded by a tearful group of local residents.

Duncan’s grief was also, to no small extent, compounded with jealousy. He never discovered how Karl -or Calindy-had managed it, but they flew up in the shuttle together, and made their final farewells on the ship. So when

Duncan glimpsed Calindy for the last time, when she waved back at him from the quarantine barrier, Karl was still with her. In that desolating moment, he did not suppose that he would ever see her again.

When Karl returned on the last shuttle flight, five hours later, he was

drawn and pale, and had lost all 50 his usual vivacity. Without a word, he had handed Duncan a small package, wrapped in brightly colored paper, and bearing the inscription LOVE FROM

CALINDY.

Duncan had opened it with trembling fingers; a bubble stereo was inside. It was a long time before he was able to see, through the mist of tears, the image it contained.

Much later that same day, as they clung together in mutual misery, an obvious question had suddenly occurred to Duncan.

“What did she give you, Karl?” he had asked.

There was a sudden pause in the other’s breathing, and he felt Karl’s body tense slightly and draw away from him. It was an almost imperceptible gesture; probably Karl was not even aware of it.

When he answered, his voice was strained and curiously defensive.

“It’s-it’s a secret. Nothing important; perhaps one day I’ll tell you.”

Even then, Duncan knew that he never would; and somehow he already yealized that this was the last night they would ever spend together.

WORLD’S END

Ground Effect Vehicles were very attractive in a low-gravity, dense-atmosphere environment, but they did tend to rearrange the landscape, especially when it consisted largely of fluffy snow. That was only a problem, however, to anyone following in the rear. When it reached its normal cruising speed of two hundred kilometers an hour, the hover sled left its private blizzard behind it, and the view ahead was excellent.

But it was not cruising at two hundred klicks; it was flat out at three, and Duncan was beginning to wish he had stayed home.

It would be very stupid if he broke his neck, on a mission where his presence was quite unnecessary, only two days before he was due to leave for

Earth.

Yet there was no real danger. They were moving over smooth, flat ammonia snow, on a terrain known to be free from crevasses. Top speed was safe, and it was fully justified. This was too good an opportunity to miss, and he had waited for it for years. No one had ever observed a wax worm in the active phase, and this one was only eighty kilometers from Oasis. The seismographs had spotted its characteristic signature, and the environment computer had given the alert. The hover sled had been through the airlock within ten minutes.

Now it was approaching the lower slopes of Mount Shackelton, the well-behaved little volcano which, after much careful thought, the original settlers had decided to accept as a neighbor. Waxworms were almost always associated with volcanoes, and some were festooned with them “like an explosion in a spaghetti factory,” as one early explorer had put it. No wonder that their discovery had caused much excitement; from the air they looked very much like the protective tunnels built by termites and other social insects on Earth.

To the bitter disappointment of the exobiologists, they had turned out to be a purely natural phenomenon-the equivalent, at a much lower temperature, of terrestrial lava tubes. The head of a wax worm moved, judging from the seismic records, at up to fifty kilometers an hour, preferring slopes of not more than ten degrees. They had even been known to go uphill for short distances, when the driving pressure was sufficiently high. Once the core of hot petrochemicals had passed along, what remained was a hollow tube as much as five meters in diameter. Waxworms were among Titan’s more benign manifestations; not only were they a valuable source of raw materials, but they could be readily adapted for storage space and even temporary surface housing-if

one could get used to the rich orchestration of alliphatic smells. The hover sled had another reason for speed; it was the season of eclipses.

Twice every Saturnian year, around the equinoxes, the sun would vanish behind the invisible bulk of the planet for up to six hours at a time.

There would be no slow waning of light, as on Earth; with shocking abruptness, the monstrous shadow of Saturn would sweep across Titan, bringing sudden and unexpected night to any traveler who had been foolish enough not to check his calendar.

Today’s eclipse was due in just over an hour, which, unless they ran into obstacles, would give ample time to reach the wax worm The sled was now driving down a narrow valley flanked by beautiful ammonia cliffs, tinted every possible shade of blue from the palest sapphire to deep indigo. Titan had been called the most colorful world in the Solar System-not excluding

Earth; if the sunlight had been more powerful, it would have been positively garish. Although reds and oranges predominated, every part of the spectrum was available somewhere, though seldom for long in the same place. The methane storms and ammonia rains were continually sculpting the landscape.

“Hello, Sled Three,” said Oasis Control suddenly. “You’ll be out in the open again in five kilometers less than two minutes at your present speed.

Then there’s a ten-kilometer slope up to the Amundsen Glacier. From there, you should be able to see the worm. But I think you’re too late-it’s almost reached World’s End.”

“Damn,” said the geologist who had been handling the sled with such effortless skill. “I was afraid of that. Something tells me I’m never going to catch a worm on the run.”

He cut the speed abruptly as a flurry of snow reduced visibility almost to zero, and for a few minutes they were navigating on radar alone through a shining white mist. A film of sticky hydrocarbon slush started to build up on the forward windows, and would soon have covered them completely if the driver had not taken remedial action A high-pitched whine filled the cabin as the sheets of tough plastic started to oscillate at near ultrasonic frequencies, and a fascinating

pat53 tern of standing waves appeared before the obscuring layer was flicked away.

Then they were through the little storm, and the jet-black wall of the

Amundsen Glacier was visible on the horizon. In a few centuries that creeping mountain would reach Oasis, and it would be necessary to do something about it. During the years of summer, the viscosity of the carbon-impregnated oils and waxes became low enough for the glacier to advance at the breath-taking speed of several centimeters an hour, but during the long winter it was as motionless as rock.

Ages ago, local heating had melted part of the glacier and formed Lake

Tuonela, almost as Stygian black as its parent but decorated by great whorls and loops where lighter material had been caught in patterns of turbulence, now frozen for eternity. Everyone who saw the phenomenon from the air for the first time thought he was being original when he exclaimed:

“Why, it looks exactly like a cup of coffee, just after you’ve stirred in the cream!”

As the sled raced over the lake, the pattern flickered past in a few minutes, too close for its swirls to be properly observed. Then there was another long slope, dotted with large boulders which could be avoided only by the full thrust of the under jets This cut speed to less than a hundred klicks, and the sled labored up toward the crest in zigs and zags, the driver cursing and looking every few seconds at his watch.

“There it is!” Duncan shouted.

Only a few kilometers away, coming out of the mist that always enveloped the flanks of Mount Shackelton, was a thin white line, like a piece of rope laid across the landscape. It stretched away downhill until it disappeared over the horizon, and the driver swung the sled around to follow its track.

But Duncan already knew that they were too late to achieve their main objective; they were much too close to World’s End. Minutes later, they were there, and the sled came to a stop at a respectful distance.

“That’s as close as I’m getting,” said the driver. “I wouldn’t like a gust to catch us when we’re skirting the edge. Who wants to go out?

We still have thirty minutes of light.” “What’s the temperature?” someone asked.

“Warm. Only fifty below. Single-layer suits will do.”

It was the first time that Duncan had been out in the open for months, but there were some skills that nobody who lived on Titan ever allowed himself to forget. He checked the oxygen pressure, the reserve tank, the radio, the fit of the neck seal-all those little details upon which his hopes of a peaceful old age depended. The fact that he would be within a hundred meters of safety, and surrounded by other men who could come to his aid in a moment, did not affect his thoroughness in the least.

Real spacers sometimes underestimated Titan, with disastrous results. It seemed altogether too easy to move around on a world where a pressure suit was unnecessary and the whole body could be exposed to the surrounding atmosphere. Nor was there any need to worry gbout freezing, even in the

Titanian night. As long as the thermosuit retained its integrity, the body’s own hundred and fifty watts of heat could maintain .a comfortable temperature indefinitely.

These facts could induce a sense of false security. A torn suit-which would be immediately noticed and repaired in a vacuum environment-might be ignored here as a minor discomfort until it was too late, and toes and fingers were quietly dropping off through frostbite. And although it seemed incredible that anyone could ignore an oxygen warning, or be careless enough to go beyond his point of no return, it had happened. Ammonia poisoning is not the nicest way to die.

Duncan did not let these facts oppress him, but they were always -there at the back of his mind. As he walked toward the worm, his feet crunching through a thin crust like congealed candle grease, he kept automatically checking the positions of his nearest companions, in case they needed him—or he needed them.

The cylindrical wall of the worm now loomed above him, ghostly white, textured with little scales or platelets which were slowly peeling off and falling to the ground. Duncan removed a mitten and laid his bare hand on the tube. It was slightly warm and there was a gentle

vibration; the core of hot liquid was still pulsing within, like blood through a giant artery. But the worm itself, controlled by the interacting forces of surface tension and gravity, had committed suicide.

While the others busied themselves with their measurements, photographs, and samples, Duncan walked to World’s End. It was not his first visit to that famous and spectacular view, but the impact had not diminished.

Almost at his feet, the ground fell away vertically for more than a thousand meters. Down the face of the cliff, the decapitated worm was slowly dripping stalactites of wax. From time to time an oily globule would break off and fall slowly toward the cloud layer far below. Duncan knew that the ground itself was another kilometer beneath that, but the sea of clouds that stretched out to the horizon had never broken since men had first observed it.

Yet overhead, the weather was remarkably clear. Apart from a little ethylene cirrus, nothing obscured the sky, and the sun was as sharp and bright as Duncan had ever seen it. He could even make out, thirty kilometers to the north, the unmistakable cone of Mount Shackelton, with its perpetual streamer of smoke.

“Hurry up and take your pictures,” said a voice in his radio. “You have less than five minutes.”

A million kilometers away, the invisible bulk of Saturn was edging toward the brilliant star that flooded this strange landscape with a light ten thousand times brighter than Earth’s full Moon. Duncan stepped back a few paces from the brink, but not so far that he could no longer watch the clouds below; he hoped he would be able to observe the shadow of the eclipse asit came racing toward him.

The light was going-going-gone. He never saw the onrushing shadow; it seemed that night fell instantly upon all the world.

He looked up toward the vanished sun, hoping to catch a glimpse of the fabled corona. But there was only a shrinking glow, revealing for a few seconds the curved edge of Saturn as the giant world swept

inexorably across the sky. Beyond that was a faint and distant star, which in another moment would also be engulfed.

“Eclipse will last twelve minutes,” said the hover sled driver. “If any of you want to stay outside, keep away from the edge. You can easily get disoriented in the darkness.”

Duncan scarcely heard him. Something had caught at his throat, almost as if a whiff of the surrounding ammonia had invaded his suit.

He could not take his gaze off that faint little star, during the seconds before Saturn wiped it from the sky. He continued to stare long after it was gone, with all its promise of warmth and wonder, and the storied centuries of its civilization.

For the first time in his life, Duncan Makenzie had seen the planet

Earth with his own unaided eyes. Part 11

I – -1 L Transit

I I

SIRIUS

After three hundred years of spaceships that were mostly fuel tanks,

Sirius was not quite believable. She seemed to have far too many windows, and there were entrance hatches in most improbable places, some of them still gaping open as cargo was loaded. At least she was taking on some hydrogen, thought Duncan sourly; it would be adding insult to economic injury if she made the round trip on a single fueling. She was capable of doing this, it was rumored, though at the cost of doubling her transit time.

It was also hard to believe that this stubby cylinder, with the smooth mirror-bright ring of the radiation baffle surrounding the drive unit like a huge sunshade, was one of the fastest objects ever built by man. Only the interstellar probes, now far out into the abyss on their centuries-long journeys, could exceed her theoretical maximum-almost one percent of the velocity of light. She would never achieve even half this speed, because she had to carry enough propel lent to slow down and rendezvous with her destination. Nevertheless, she could make the voyage from Saturn to Earth in twenty days, despite a minor detour to avoid the hazards-largely psychological-of the asteroid belt.

The forty-minute flight from surface to parking orbit was not Duncan’s first experience of space; he had made several brief trips to neighboring moons, aboard this same shuttle. The Titanian passenger fleet consisted of exactly five vessels, and as none possessed the expensive luxury of centrifugal gravity, all safety belts were secured throughout the voyage.

Any passenger who wished to sample the joys and hazards of weightlessness would have just under two hours to experience it aboard

Sirius, before the drive started to operate. Although Duncan had always felt completely at ease in free fall, he let the stewards float him, an inert and unresisting package, through the airlock and into the ship.

It had been rather too much to expect the Centennial Committee to provide a single cabin-there were only four on the ship-and Duncan knew that he would have to share a double. L.3 was a minute cell with two folding bunks, a couple of lockers, two seats-also folding-and a mirror-vision screen.

There was no window looking out into space; this, the Welcome Aboard! brochure carefully explained, would create unacceptable structural hazards.

Duncan did not believe this for a moment, and wondered if the designers feared an attempt by claustrophobic passengers to claw a way out.

And there were no toilet facilities-these were all in an adjacent cubicle, which serviced the four cabins around it. Well, it was only going to be for a few weeks…. Duncan’s spirits rose somewhat after he had gained enough confidence to start exploring his little world. He quickly learned to visualize his location by following the advice printed on the shipboard maps; it was convenient to think of Sirius as a cylindrical tower with ten floors. The fifty cabins were divided between the sixth and seventh floors. Immediately below, on the fifth level, was the lounge, recreation and dining area.

The territory above these three floors was forbidden to passengers. Going upward, the remaining levels were Life Support, Crew Quarters, and-forming a kind of penthouse with all-round visibility-the Bridge. In the other direction, the four levels were Galley, Hold, Fuel, and Propulsion. It was a logical arrangement, but it would take Duncan some time to discover that the Purser’s Office was on the kitchen level, the surgery next to the freight compartment, the gym in Life Support, and the library tucked away in an emergency airlock overlapping levels Six and Seven…. During the circumnavigation of his

new home, Duncan encountered a dozen other passengers on a 61 similar voyage of exploration, and exchanged the guarded greetings appropriate among strangers who will soon get to know each other perhaps all too well. He had already been through the passenger list to see if there was anyone on board he knew and had found a few familiar Titanian names, but no close acquaintances. Sharing cabin L.3, he had discovered, was a Dr. Louise

Chung; but the parting with Marissa still hurt too much for the “Louise” to arouse more than the faintest flicker of interest.

I In any event, as he found when he returned to L.3, Dr. Chung was a bright little old lady, undoubtedly on the far side of a hundred, who greeted him with an absent-minded courtesy which, even by the end of the voyage, never seemed to extend to a complete recognition of his existence. She was, he soon discovered, one of the Solar System’s leading mathematical physicists, and the authority on resonance phenomena among the satellites of the outer planets. For half a century she had been trying to explain why the gaps in

Saturn’s rings were not exactly where all the best theories demanded.

The two hours ticked slowly away, finally seeming to move with a rush toward the expected announcement: “This is Captain Ivanov speaking at minus five minutes. All crew members should be on station or standby, all passengers should have safety straps secured. Initial acceleration will be one hundredth gravity-ten centimeters second squared. I repeat, one hundredth gravity. This will be maintained for ten minutes while the propulsion system undergoes routine checks.”

And suppose it doesn’t pass those checks? Duncan asked himself. Do even the mathematicians know what would happen if the Asymptotic Drive started to malfunction? This line of thought was not very profitable, and he hastily abandoned it.

“Minus four minutes. Stewards check all passengers secured.”

Now that instruction could not possibly be obeyed. There were three hundred twenty-five passengers, half of them in their cabins and the

other half in the two lounges, and there was no way in which the dozen harassed stewards could see that all their charges were behaving. They had made one round of the ship at minus thirty and minus ten minutes, and passeligers who had cut loose since then had only themselves to blame. And anyone who could be hurt by a hundredth of a gee, thought Duncan, certainly deserved it. Impacts at that acceleration had about the punch of a large wet sponge.

“Minus three minutes. All systems normal. Passengers in Lounge B will see

Saturn rising.”

Duncan permitted himself a slight glow of self satisfaction. This was precisely why, after checking with one of the stewards, he was now in Lounge B. As Titan always kept the same face turned toward its pr tary the spectacle of the great globe climbing abe the horizon was one that could never be seen from the surface, even if the almost perpetual over cast of hydrocarbon clouds had permitted.

That blanket of clouds now lay a thousand kilometers below, hiding the world that it protected from the chill of space. And then suddenly-unexpectedly, even though he had been waiting for it-Saturn. was rising like a golden ghost.

In all the known universe, there was nothing to compare with the wonder he was seeing now. A hundred times the size of the puny Moon that floated in the skies of Earth, the flattened yellow globe looked like an object lesson in planetary meteorology. Its knotted bands of cloud could change their appearance almost every hour, while thousands of kilometers down in the hydrogen-methane atmosphere, eruptions whose cause was still unknown would lift bubbles larger than terrestrial continents up from the hidden core.

They would expand and burst as they reached the limits of the atmosphere, and in minutes Saturn’s furious ten-hour spin would have smeared them out into long colored ribbons, stretching halfway round the planet.

Somewhere down there in that inferno, Duncan reminded himself with awe,

Captain Kleinman had died seventy years ago, and so had part of Grandma

Ellen. In all that time, no one had attempted to return. Saturn still

represented one of the largest pieces of unfinished business in the Solar System-next, perhaps, to the smoldering hell of Venus.

The rings themselves were still so inconspicuous that it was easy to overlook them. By a cosmic irony, all the inner satellites lay in almost the same plane as the delicate, wafer-thin structure that made Saturn unique. Edge on, as they were now, the rings were visible only as hairlines of light jutting out on either side of the planet, yet they threw a broad, dusky band of shadow along the equator.

In a few hours, as Sirius rose above the orbital plane of Titan, the rings would open up in their full glory. And that alone, thought Duncan, would be enough to justify this voyage.

“Minus one minute…”

He had never even heard the two-minute mark; the great world rising out of the horizon clouds must have held him hypnotized. In sixty seconds, the automatic sequencer in the heart of the drive unit would’ initiate its final mysteries. Forces which only a handful of living men could envisage, and none could truly understand, would awaken in their fury, tear Sirius from the grip of Saturn, and hurl her sunward toward the distant goal of

Earth. “.. . ten seconds… five seconds … ignition!”

How strange that a word that had been technologically obsolete for at least two hundred years should have survived in the jargon of astronautics!

Duncan barely had time to formulate this thought when he felt the onset of thrust. From exactly zero his weight leaped up to less than a kilogram. It was barely enough to dent the cushion above which he had been floating, and was detectable chiefly by the slackening tension of his waist belt.

Other effects were scarcely more dramatic. There was a distinct change in the timbre of the indefinable noises which never cease on board a spacecraft while its mechanical hearts are operating; and it seemed to

Duncan that, far away, he could hear a faint hissing. But he was not even sure of that.

And then, a thousand kilometers below, he saw the unmistakable evidence that Sirius was indeed breaking away from her orbit. The ship had been

driving 64 into night on its final circuit of Titan, and the wan sunlight had been swiftly fading on the sea of clouds far below. But now a second dawn had come, in a wide swathe across the face of the world he was soon to leave.

For a hundred kilometers behind the accelerating ship, a column of incandescent plasma was splashing untold quintillions of candlepower out into space and across the carmine cloud scape of Titan. Sirius was falling sunward in greater glory than the sun itself.

“Ten minutes after ignition. All drive checks complete. We will now be increasing thrust to our cruise level of point two gravities-two hundred centimeters second squared.”

And now, for the first time, Sirius was showing what she could do. In a smooth surge of power, thrust and weight climbed twenty-fold and held steady. The light on the clouds below was now so strong that it hurt the eye. Duncan even glanced at the still-rising disc of Saturn to see if it too showed any sign of this fierce new sun. He could now hear, faint but unmistakable, the steady whistling roar that would be the background to all life aboard the ship until the voyage ended. It must, he thought, be pure coincidence that the awesome voice of the Asymptotic Drive sounded so much like that of the old chemical rockets that first gave men the freedom of space. The plasma hurtling from the ship’s reactor was moving a thousand times more swiftly than the exhaust gases of any rocket, even a nuclear one; and how it created that apparently familiar noise was a puzzle that would not be solved by any naive mechanical intuition.

“We are now on cruise mode at one-fifth gee. Passengers may unstrap themselves and move about freely-but please use caution until you are completely adapted.”

That won’t take me very long, thought Duncan as be unbuckled himself; the ship’s acceleration gave him his normal, Titan weight. Any residents of the

Moon would also feel completely at home here, while Martians and

Terrans would have a delightful sense of buoyancy. The lights in the lounge, which had been dimmed almost to extinction for better viewing of the spectacle outside, slowly brightened to normal. The few first magnitude stars that had been visible disappeared at once, and the gibbous globe of Saturn became bleached and pale, losing all its colors.

Duncan could restore the scene by drawing the black curtains around the observation alcove, but his eyes would take several minutes to readapt. He was wondering whether to make the effort when the decision was made for him.

There was a musical “Ding-dong-ding,” and a new voice, which sounded as if it came from a social stratum several deLyrees above the Captain’s, anuounced languidly: “This is the Chief Steward. Will passengers kindly note that First Seating for lunch is at twelve hundred, Second Seating at thirteen hundred, Last Seating at fourteen hundred. Please do not attempt to make any changes without consulting me. Thank you.” A less peremptory

“Dong-ding-dong” signaled end of message.

Looking at the marvels of the universe made you hungry, Duncan instantly discovered. It was already 1150,“and he was glad that he was in the First