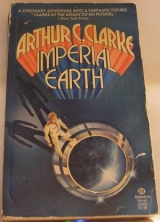

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Grandma had polished a section a few millimeters on a side, and the specimen now lay on the stage of a binocular microscope, with a beam of pseudo white light from a tri chromatic laser shining into it. Most of the room illumination had been switched off, but refracted and reflected spots, many of them completely dispersed into their three component colors, glowed steadily from unexpected places on walls and ceiling. The room might have been some magician’s or alchemist’s cell-as, indeed, in a way it was. In earlier ages, Ellen Makenzie would probably have been regarded as a witch.

Calindy stared through the microscope for a long time, while Duncan waited more or less patiently. Then, with a whispered “It’s beautiful-I’ve never seen anything like it!” she had reluctantly stepped aside …. A hexagonal corridor of light, dwindling away to infinity, outlined by millions of sparkling points in a geometrically perfect array. By changing focus, Duncan could hurtle down that corridor, without ever coming to an end. How incredible that such a universe lay inside a piece of rock only a millimeter thick!

The slightest change of position, and the glittering hexagon vanished; it depended critically on the angle of illumination, as well as the orientation of the crystal. Once it was lost, even Grandma’s skilled hands took minutes to find it again.

“Quite unique,” she had said happily (Duncan had never seen her so cheerful), “and I’ve no explanations-merely half a dozen theories. I’m not even sure if we’re seeing a real structure-or some kind of moire pattern in three dimensions, if that’s possible….”

That had been fifteen years ago-and in that time, hundreds of theories had been proposed and demolished. It was widely agreed, however, that titanite’s extraordinarily perfect lattice structure must have been produced by a combination of extremely low temperatures and total absence of gravity. If this theory was correct, it could not have originated on any planet, or much nearer to the Sun than the orbit of Neptune. Some scientists had even built a whole elaborate theory of “interstellar crystallography” on this assumption.

There had been even wilder suggestions. Something as odd as titanite had, naturally, appealed to Karl’s speculative urges.

“I don’t believe it’s natural,” he had once told Duncan. “A material like that couldn’t happen. It’s an artifact of a superior civilization-like-oh-one of our crystal memories.”

Duncan had been impressed. It was one of those theories that sounded just crazy enough to be true, and every few years someone “rediscovered” it. But as the debate raged on inconclusively, the public soon lost interest; only the geologists and gemologists still found titanite a source of endless fascination-as Manderstahm had now demonstrated.

Makenzies always kept their promises, even in the most trifling matters.

Duncan would send a message off to Colin the first thing in the morning.

There was no hurry; and that, he expected and half hoped, would be the last he would hear of it.

Very gently, he replaced the titanite cross in its setting between the

F,

N, U, and V pentominoes. One day, he really must make a sketch of the configuration.

If the pieces ever fell out of the box, it might take him hours to get them back again….

THE RIVALS

After the encounter with Mortimer Keynes Duncan licked his wounds in silence for several days. He did not feel like discussing the matter with his usual confidants, General George and Ambassador Farrell. And though he did not doubt that Calindy would have all the answers-or could find them quickly-he also hesitated to call her. Instinct, rather than logic, told him that it might not be a good idea. When he looked into his heart, Duncan had to admit ruefully that though he certainly desired

Calindy, and perhaps even loved her, he did not trust her.

The Classified Section of the Comsole was not much use. When he asked for information on cloning services, he got several dozen names, none of which meant anything to him. He was not surprised to see that the list no longer included Keynes; when he checked the surgeon’s personal entry, it printed out “Retired.” He might have saved himself some embarrassment if he had discovered this earlier, but who could have guessed?

Like many such problems, this one solved itself unexpectedly. He was groaning beneath Bernie Patras’ ministrations when he suddenly realized that the person who could help was right here, pulverizing him with merciless skill.

Whether or not a man has any secrets from his valet, he certainly has none from his masseur. With Bernie, Duncan had established a cheerful, bantering relationship, without detracting from the serious professionalism of the other’s therapy-thanks to which he was not merely mobile, but still steadily gaining strength.

Bernie was an inveterate gossip, fall of scandalous stories, but Duncan had noticed that he never revealed names and was as careful to protect his sources as any media reporter. For all his chattering, he could be trusted; and he also had any entree he wished to the medical profession. He was just the man for the job.

“Bernie, there’s something I’d like you to do for me.92

“Delighted. Just tell me whether it’s boys or girls, and how many of each, with approximate shapes and sizes. I’ll fill in the details.”

“This is serious. You know I’m a clone, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

Duncan had assumed as much; it was not one of the Solar System’s best-kept secrets.

“Ouch-have you ever heard of Mortimer Keynes?”

“The genetic surgeon? Of course.”

“Good. He was the man who cloned me. Well, the other day I called him, just to-ah-say hello. And he behaved in a very strange way. In fact, he was almost rude.”

“You didn’t call him “Doctoe? Surgeons often hate that.”

“No-at least, I don’t think so. It wasn’t really anything on a personal level. He just tried to tell me that cloning was a bad idea, and he was against it. I felt I should apologize for existing.”

“I can understand your feelings. What do you want me to do? My rates for assassination are quite high, but easy terms can be arranged.”

“Before we get that far, you might make some inquiries among your medical friends. I’d very much like to discover why Sir Mortimer changed his mind -that is, if anyone knows the reason.”

“I’ll find out, don’t worry-though it may take a few days.” Bernie was obviously delighted at the challenge; he was also unduly pessimistic in his estimate, for he called Duncan the very next morning.

“No problem,” he said triumphantly. “Everyone knows the story-I should have remembered it my~ self. Are you ready to record? A few kilobits of the

World Times coming over…” The tragicomedy had reverberated around the Terran news services for several months, more than fifteen years ago, and echoes of it were still heard from time to time. It was an old tale-as old as human history, in some form or other. Duncan had read only a few paragraphs before he was able to imagine the rest.

There had been the brilliant but aging surgeon and his equally brilliant young assistant, who in the natural course of events would have been his successor. They had known triumphs and disasters together, and had been so closely linked that the world had thought of them almost as one person.

Then there had been a quarrel, over a new technique which the younger man had developed. There was no need, he claimed, to wait for the immemorial nine months between conception and birth, now that the entire process was under control. If certain precautions were taken to safeguard the health of the human foster mother who carried the fertilized egg, there was no reason why pregnancy should last more than two or three months.

Needless to say, this claim excited wide attention. There was even facetious talk of “instant clones.” Mortimer Keynes had not disputed his colleague’s techniques, but he deplored any attempt to put them into practice. With a conservatism that some thought curiously inappropriate, he agrued that Nature had chosen that nine months for very good reasons, and that the human race should stick to it.

Considering the violence that cloning did to the normal process of reproduction, this seemed a rather strange attitude, as many critics hastened to point out. This only made Sir Mortimer even more stubborn, and reading between the lines Duncan felt fairly certain that the surgeon’s expressed objections were not the real ones. For some unknown and probably unknowable reason, he had experienced a crisis of conscience; what he was now opposing was not merely the shortening of the gestation period, but the entire process of cloning itself.

The younger man, of course, disagreed completely. The debate had become more and more bitter-also more and more public, as it was inflamed by sensation-seeking hangers-on who wanted to see a good fight.

After one abortive attempt at reconciliation, the partnership split up, and the two men had never spoken to each other again. A major problem at medical congresses for the last decade had been to ensure that they were not present simultaneously at any meeting.

That had been the end of Mortimer Keynes’s active career. The famous clinic he had established was closed down, though he still kept his Harley Street office and did a little consultation. His ex-partner, who had a remarkable gift for acquiring public and private funds, promptly established a new base and continued his experiments.

As Duncan read on, with increasing curiosity and excitement, he realized that here was the man he needed. Whether he would take advantage of the highspeed cloning technique he could decide later; it was certainly interesting to know that the option existed, and that if he wished, he could return to Titan months in advance of his original schedule.

Now to locate Sir Mortimer’s ex-colleague and successor. It was lucky that the search did not have to rely on the name alone, for it was one that occurred in some form or other half a million times in the Earth Directory.

But he had only to consult the Classified Section-often referred to, for some mysterious reason lost in the depths of time, by the utterly meaningless phrase “Yellow Pages.”

And so, on a small island off the east coast of Africa, Duncan discovered

El Hadj Yehudi ben Mohammed.

He had scarcely made arrangements to fly to Zanzibar when a small bombshell arrived from Titan. It bore Colin’s identification number, but he was unable to make sense of it until he realized that it was both in cipher and the Makenzie private code. Even after two processing trips through his

Minisec, it was still somewhat cryptic: PRIORITY AAA SECURITY AAA

NO RECORD OF ANY SHIPMENT TITANrrB REGISTERED BUREAU OF RESOURCES LAST

TWO

YEARS. POSSIBLE INFRINGEMENT FINANCE REGULATIONS IF PRIVATE SALE FOR

CONVERTIBLE SO LARS NOT APPROVED BY BANK OF TITAN. PERSISTENT RUMOR

MAJOR

DISCOVERY ON OUTER MOON. ASKING HELMER TO INVESTIGATE. WILL REPORT

SOONEST.

COLIN.

Duncan read the message several times without any immediate reaction. Then, slowly, the pieces of the puzzle began to drift around into new configurations, and a pattern started to emerge. It was one that Duncan did not like at all.

Naturally, Colin would have gone to Armand Helmer, Controller of Resources; the export of minerals came under his jurisdiction. Moreover, Armand was a geologist-in fact, he had made one small titanite find himself, of which he was inordinately proud.

Was it conceivable that Armand himself might be involved? The thought flashed through Dancan’s mind, but he dismissed it instantly. He had known

Armand all his life and despite their many political and personal differences, he did not for a moment believe that the Controller would get involved in any illegality-especially one that concerned his own Bureau.

And for what purpose? Merely to accumulate a few thousand so lars in some terrestrial bank? Armand was now too old, and too gravity-conditioned, ever to return to Earth, and he was not the kind of man who would break the law for so trivial a purpose as importing Terran luxuries. Especially as such chicanery was always discovered, sooner or later; smugglers could never resist displaying their treasures. And then there would be another acquisition for the impecunious Titan Museum, while the criminal would be barred from all the best places for at least a month.

No, Armand could be excluded; but what of his son? The more Duncan, considered this possibility, the more likely it seemed. He had no proof whatsoever-OnlY an allaY of facts all pointing in one direction.

Consider: Karl had always been daring and adventurous, willing to run risks for what he believed sufficiently good reasons. As a boy, he had taken a positive delight in circumventing regulations-except, of course, those basic safety rules that no sane resident of Titan would ever challenge.

If titanite had been discovered on one of the other satellites, Karl would be in an excellent position to take advantage of it. In the last three years, he had been on half a dozen Titan-Terran surveys. To Duncan’s certain knowledge, he was one of the few men who had been to Enceladus,

Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Hyperion, Iapetus, Phoebe, Chronus, Prometheus. And now he was on remote Mnemosyne….

Already Duncan could draw up a seductively plausible scenario. Karl might even have made the find himself. Certainly he would have seen all the specimens coming aboard the survey ship, and his well known charm would have done the rest. Indeed, the actual discoverer might never have known what he had found. Few people had seen raw titanite, and it was not easy to identify until it had been polished.

Then it would have been a simple matter of sending a small package to

Earth, pprhaps on one of the resupply ships which did not even call at

Titan. (What would be the legal situation then? That could be tricky. Titan had jurisdiction over the other permanent satellities, but its claim to the obvious temporary ones like Phoebe & Co. was still in dispute. It was possible that no laws had been broken at all …. )

But this was sheer speculation. He had not the slightest hard evidence.

Why, indeed, had he thought of Karl at all in this context?

He reread the message, still glowing on the

Comsole monitor: MAJOR DISCOVERY ON OUTER

MOON. ASKING HELMER… That was what had triggered this line of ‘thought. Guilt by association, perhaps the juxtaposition might be pure coincidence.

But the Makenzies could read each other’s minds, and’ Duncan knew that

the phraseology was deliberate. There was no need for Colin to have mentioned Helmer; he was sending out an early warning signal.

It was ridiculous to pile speculation upon speculation, but Duncan could not resist the next step. Assuming that Karl was involved-why?

Karl might take risks, might even get involved in petty illegalities, but it would be for some good purpose. If-and it was still an enormous “if”-he was trying to accumulate funds on Earth, he must have a long-range objective in mind. The most obvious was the establishment of a power base-precisely as Duncan was doing.

He must also have an agent here, someone he could trust implicitly. That would not be difficult; Karl had met hundreds of Terrans “Oh, my God,” Duncan breathed. “That explains everything….”

He wondered if he should cancel his trip to Zanzibar; no, that took priority over all else, except the speech he had come a billion kilometers to deliver. In any case, he did not see what more he could do here in

Washington until he had further news from home.

He was still operating on pure guesswork, without one atom of proof. But there was a cold, dead feeling in the general region of his heart; and suddenly, for no good reason at all, Duncan thought of that solitary iceberg, gliding southward on the hidden current toward its irrevocable destiny.

THE ISLAND OF DR. MOHAMMED

El Hadj’s deputy, Dr. Todd, was one of those medical men who seem, not always justifiably, to radiate an aura of confidence. This despite his relative youth and informality; for reasons which Duncan never

discovered, all his colleagues used his nickname, Sweeney. ““I’m sorry you won’t meet El Hadj this time,” he said apologetically. “He had to rush to Hawaii, for an emergency operation.”

“I’m surprised that’s necessary, in this age.”

“Normally, it’s not. But Hawaii’s almost exactly on the other side of the world-which means you have to work through two com sats in series. During tele surgery that extra time delay can be critical.”

So even on Earth, thought Duncan, the slowness of radio waves can be a problem. A half-second lag would not matter in conversation; but between a surgeon’s hand and eye, it might be fatal.

“Until twenty years ago,” Dr. Todd explained, “this was a famous marine biology lab. So it had most of the facilities we need-including isolation.”

“Why is that necessary?” asked Duncan. He had wondered why the clinic was in such an inconveniently out-of-the-way spot.

“There’s a good deal of emotional interest in our work, and we have to control visitors. Despite air transportation, you can still do that much easier on an island than anywhere else. And above all, we have to protect our Mothers. They may not be very intelligent, but they’re sensitive, and don’t like being stared at.”

“I’ve not seen any yet.”

“Do you really want to?”

That was a difficult question to answer, for Dun can felt his emotions tugging in opposite directions.

Thirty-one years ago, he must have been born in a place not unlike this, though probably not as sT)ec tacularly beautiful. If he had gone full term-and in those days, he assumed, all clones did so-some un known woman had carried him in her body for at least eight months after implantation. Was she still alive? Did any record of her name still exist, or was she merely a number in a computer file? Perhaps not even that, for the identity of a foster mother was not of the slightest biological importance. A purely mechanical womb could have served as well, but there had never been any real need to perfect so complex a

device. In a world where reproduction was strictly limited, there would always be plenty of volunteers; the only problem was selecting them.

Duncan had no memory whatsoever of his unknown foster mother or of the months he must have spent on Earth as a baby. Every attempt to penetrate the fog that lay at the very beginning of his childhood was a failure. He could not be certain if this was normal, or whether the earliest part of his life was hidden by deliberately induced amnesia. He suspected the latter, since he felt a distinct reluctance ever to investigate the subject in any detail.

When he formed the concept “Mother” in his mind, he instantly saw Colin’s wife, Sheela. Her face was his earliest memory, her affection his first love, later shared with Grandma Ellen. Colin had chosen -carefully and had learned from Malcolm’s mistakes.

Sheela had treated Duncan exactly like her own children, and he had never thought of Yuri and Glynn as anything except his older brother and sister.

He could not remember when he had first realized that Colin was not their father, and that they bore no genetic relationship to him whatsoever. Somehow, it had never seemed to matter.

He appreciated, now, the unobtrusive skills that had gone into the creation of so well adjusted a “family”; it would not have been possible in an earlier age of exclusive marriage and sexual possessiveness. Even today, it was no easy task. He hoped that he and Marissa would be equally successful, and that Clyde and Carline would accept little Malcolm as their brother, just as wholeheartedly as Yuri and Glynn had once accepted him…. “I’m sorry,” said Duncan. “I was daydreaming.”

“Can’t say I blame you; this place is too damned beautiful. I sometimes have to draw the curtains when I want to do any work.”

That was easy to believe-yet beauty was not the first impression to strike

Duncan when he landed on the island. Even now, his dominant feeling was one of awe, mixed with more than a trace of fear.

Starting a dozen meters away, and filling his field of vision right out to the sharp blue line of the horizon, was more water than he had ever

imagined. It 204 was true that he-had seen Earth’s oceans from space, but from that Olympian vantage point it had been impossible to envisage their true size. Even the greatest of seas was diminished, when one could flash across it in ten minutes.

This world was indeed misnamed. It should have been called Ocean, not

Earth. Duncan performed a rough mental calculation-one of the skills the

Makenzies had carefully retained, despite the omnipresent computer. Radius six thousand-and his eye was about six meters above sea level-that made it simple-six root two, or near enough eight kilometers. Only eight! It was incredible; he could easily have believed that the horizon was a hundred kilometers away. His vision could not span even one percent of the distance to the other shore…. And what he could see now was only the two dimensional skin of an alien universe, teeming with strange life forms seeking whom they might devour.

To Duncan, that expanse of peaceful blue concealed a word much more hostile, and more terrifying, than Space. Even Titan, with its known dangers, seemed benign in comparison.

And yet there were children out there, splashing around in the shallows, and disappearing underwater for quite terrifying lengths of time. One of them, Duncan was certain, had been gone for well over a minute.

“Isn’t that dangerous?” he asked anxiously, gesturing toward the lagoon.

“We don’t let them go near the water until they’re well trained. And if you must drown yourself, this is the place for it-with some of the best medical facilities in the world. We’ve had only one permanent death in the last fifteen years. Revival would have been possible even then, but after an hour underwater, brain damage is irreversible.”

“But what about sharks and all the other big fish?”

“We’ve never had an attack inside the reef, and only one outside it. That’s a small price to pay for admission to Fairyland. We’re taking out the big trimaran tomorrow-why don’t you come along?” “I’ll think

about it, “Duncan answered evasively. 205 “Oh-I suppose you’ve never been underwater before.”

“I’ve never been on it—except in a swimming Pool.”

“Well, you’ve nothing to lose. Though we won’t complete the tests for another forty-eight hours, I’m sure we’ll be able to clone successfully from the genotypes you’ve given. So your immortality insurance is taken care of.”

“Thank you very much,” said Duncan dryly. “That makes all the difference.”

He remembered Commander Innes’ invitation to the Caribbean reefs, and his instant though unexpressed refusal. But those mere children were obviously enjoying themselves, and their confidence was a reproach to his manhood.

The pride of the Makenzies was at stake; he looked glumly at that appalling mass of water, and realized that he would have to do something about it before he left the island.

He had never felt less enthusiastic about any project in his life.

The night was beautiful, blazing with more stars than any man could ever see from the surface of Titan, however long he lived. Though it was only nineteen hundred hours-too early for dinner, let alone sleep-the sun might never have existed, so total was the darkness away from the illumination of the main buildings, and of the little lights strung along the paths of crushed coral.

From somewhere in that darkness came the sound of music-a rhythmical throbbing of drums, played with more enthusiasm than skill. Rising above this steady beat were occasional bursts of song, and women’s voices calling to one another. Those voices made Duncan suddenly lonely and homesick. He started to walk along the narrow path in the general direction of the revelry.

After wandering down several blind alleys—ending up once in a charming sunken garden, which he left with profuse apologies to the couple busily occupying it-he came to the clearing where the party was in 206

progress. At its center, a large bonfire was lofting a column of smoke and flames toward the stars, and a score of figures was dancing around it, like the priestesses of some primitive religion.

They were not dancing with much grace or vigor; in fact, it would be more truthful to say that most of them were circulating in a dignified waddle.

But despite their obvious advanced state of pregnancy, they were clearly enjoying themselves, and were being as active as was advisable in the circumstances.

It was a grotesque yet strangely moving spectacle, arousing in Duncan a mixture of pity and tenderness -even an impersonal and wholly un erotic love. The tenderness was that which all men feel in the imminent presence of birth and the wonder of their own existence; the pity had a different cause.

Ugliness and deformity were rare on Titan-and rarer still on Earth, since both could almost always be corrected. Almost-but not always. Here was proof of that.

Most of these women were extremely plain; some were ugly; a few were frankly hideous. And though Duncan noticed two or three who might even pass as beautiful, it needed only a glance to show that they were mentally subnormal. Had his long-dead sis tee Anitra survived into adult life, she would have been at home in this strange assembly.

If the dancers-and those others merely sitting around, banging away at drums and sawing on fiddles.-had not been so obviously happy it would have been a disturbing, perhaps even a sickening spectacle. It did not upset

Duncan. Though he was startled, he was prepared for it.

He knew how the foster mothers were chosen. The first requirement, of course, was that they should have no gynecological defects. That demand was easy to satisfy. It was not so simple to cope with the psychological factors, and it might have been a virtually impossible task in the days before the world’s population was computer-profiled.

There would always be women who desperately yearned to bear children, but who for one reason or another could not fulfill their destiny. In

earlier ages, most of them would have been doomed to spinsterly frustration; indeed, even in this world of 2276, many of them still were. There were more would-be mothers than the controlled birth rate could satisfy, but those who were especially disadvantaged could find some compensation here. The losers in the lottery of Fate could yet win a consolation prize, and know for a few months the happiness that would otherwise be denied them.

And so the World Computer had been programmed as an instrument of compassion. This act of humanity had done more than anything else to silence those who objected to cloning.

Of course, there were still problems. All these Mothers must know, however dimly, that soon after birth they would be separated forever from the child they were to bring into the world. That was not a sorrow that any man could understand; but women were stronger than men, and they would get over it -more often than not by taking part again in the creation of another life.

Duncan remained in the shadows, not wishing to be seen and certainly not wishing to get involved. Some of those incipient Mothers could crush him to a pulp if they grabbed him and whirled him into the dance. He had now noticed that a handful of men -presumably medical orderlies or staff from the clinic-were circulating light-heartedly with the Mothers and entering into the spirit of the festivities.

He could not help wondering if there had also been some deliberate psychological selection here. Several of the men looked very effeminate, and were treating their partners with what could only be called sisterly affection. They were obviously dear friends; and that was all they would ever be.

No one could have seen, in the darkness, Duncan’s smile of amused recollection. He had just remembered-for the first time in years-a boy who had fallen in love with him in his late teens. It is hard to reject anyone who is devoted to you, but although Duncan had good-naturedly succumbed a few times to Nikki’s blandishments, he had eventually managed to discourage his admirer, despite torrents of

tears. Pity is not a good basis for any relationship, and Duncan could never feel quite happy with someone whose affections were exclusively polarized toward one sex. What a contrast to the aggressive normality of Karl, whq, did not give a damn whether he had more affairs with boys or girls, or vice versa.

At least, until the Calindy episode … These memories, so unexpectedly dredged up from the past, made Duncan aware of the complicated emotional crosscurrents that must be sweeping through this place. And he suddenly recalled that disturbing conversation-or, rather, monologue-with Sir Mortitimer Keynes…. That he would follow in the steps of Colin, and of Malcolm before, was something that Duncan had always taken for granted, without any discussion.

But now he realized, rather late in the day, that there was a price for everything, and that it should be considered very carefully before the contract was finally signed.

Cloning was neither good nor bad; only its purpose was important. And that purpose should not be one that was trivial or selfish.

GOLDEN REEF

The vivid green band of palms and the brilliant white crescent of the perfect beach were now more than a kilometer away, on the far side of the barrier reef. Even through the dark glasses which he dared not remove for a moment, the scene was almost painfully bright; when he looked in the direction of the sun, and caught its sparkle off the ocean swell, Duncan was completely blinded. Though this was a tritling matter, it enhanced his feeling of separation from all his companions.

True, most of them also wore dark glasses-but in their case it was a convenience, not a necessity.

Despite his wholly terrestrial genes, it seemed that he had adapted irrevocably to the light of a world ten times farther from the sun.

Beneath the smoothly sliding flanks of the triple hull, the water was so clear that it added to Duncan’s feeling of insecurity. The boat seemed to be hanging in midair, with no apparent means of support, over a dappled sea bed five or ten meters below. It seemed strange that this should worry him, when he had looked down on Earth from orbit, hundreds of kilometers above the atmosphere.