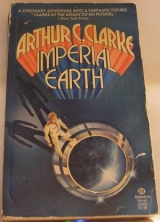

Текст книги "Imperial Earth"

Автор книги: Arthur Charles Clarke

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

But surely there must be more to it than this. The game couldn’t have finished already. No, Grandma still had something up her sleeve.

“Now listen carefully, Duncan. Each of these figures-they’re called pentominoes, by the way-is obviously the same size, since they’re all made from five identical squares. And there are twelve of them, so the total area is sixty squares. Right?”

GUm … yes.”

“Now sixty is a nice round number, which you can split up in lots of ways.

Let’s start with ten multiplied by six, the easiest one. That’s the area of this little box-ten units by six units. So the twelve pieces should fit exactly into it, like a simple jigsaw puzzle.”

Duncan looked for traps-Grandma had a fondness for verbal and mathematical paradoxes, not all of them comprehensible to a ten-year-old victim but he could find none. If the box was indeed the size Grandma said, then the twelve pieces should just fit into it. After all, both were sixty units in area.

Wait a minute … the area might be the same, but the shape could be wrong.

There might be no way of 33 making the twelve pieces fit this rectangular box, even though it was the right size.

“I’ll leave you to it,” said Grandma, after he had shuffled pieces around for a few minutes. “But I promise you this-it can be done.”

Ten minutes later, Duncan was beginning to doubt it. It was easy enough to fit ten of the pieces into the frame-and once he had managed eleven. Unfortunately the hole then left in the jigsaw was not the same shape as the piece that remained in his hand —even though, of course, it was of exactly the same area. The hole was an X, the piece was a Z…. Thirty minutes later, he was fairly bursting with frustration. Grandma had left him completely alone, while she conducted an earnest dialogue with her computer; but from time to time she gave him an amused glance, as if to say

“See-it isn’t as easy as you thought….”

Duncan was stubborn for his age. Most boys of ten would have given up long ago. (It never occurred to him, until years later, that Grandma was also doing a neat job of psychological testing.) He did not appeal for help for almost forty minutes. – . Grandma’s fingers flickered over the mosaic. The U and X and L slid around inside their restraining frame-and suddenly the little box was exactly full. The twelve pieces had been perfectly fitted into the jigsaw.

“Well, you knew the answerl” said Duncan, rather lamely.

“The answer?” retorted Grandma. “Would you care to guess how many diflerent ways those pieces can be fitted into their box?”

There was a catch here-Duncan was sure of it. He hadn’t found a single solution in almost an hour of effort-and he must have tried at least a hundred arrangements. But it was possible that there might be-oh-a dozen different answers.

“I’d guess there might be twenty ways of putting those pieces into the box,” he replied, determined to be on the safe side.

“Try again.” That was a danger signal. Obviously, there was 34 much more to this business than met the eye, and it would be safer not to commit himself.

Duncan shook his head.

“I can’t imagine.~P

“Sensible boy. Intuition is a dangerous guide though sometimes it’s the only one we have. Nobody could ever guess the right answer. There are more than two thousand distinct ways of putting these twelve pieces back into their box. To be precise, 2,339. What do you think of that?”

It was not likely that Grandma was lying to him, yet Duncan felt so humiliated by his total failure to find even one solution that he blurted out: “I don’t believe it!”

Grandma seldom showed annoyance, though she could become cold and withdrawn when he had offended her. This time, however, she merely laughed and punched out some instructions to the computer.

“Look at that,” she said.

A pattern of bright lines had appeared on the screen, showing the set of all twelve pentominoes fitted into the six-by-ten frame. It held for a few seconds, then was replaced by another obviously different, though Duncan could not possibly remember the arrangement briefly presented to him. Then came another… and another, until Grandma canceled the program.

“Even at this fast rate,” she said, “it takes five hours to run through them all. And take my word for it-though no human being has ever checked each one, or ever could-they’re all different.”

For a long time, Duncan stared at the collection of twelve deceptively simple figures. As he slowly assimilated what Grandma had told him, he had the first genuine mathematical revelation of his life. What had at first seemed merely a childish game had opened endless vistas and horizons-though even the brightest of ten-year-olds could not begin to guess the full extent of the universe now opening up before him.

This moment of dawning wonder and awe was purely passive; a far more intense explosion of intellectual delight occurred when he found his

first very own solution to the problem. For weeks he carried around with him the set of twelve pentominoes in their plastic box, playing with them at every odd moment. He got to know each of the dozen shapes as personal friends, calling them by the letters which they most resembled, though in some cases with a good deal of imaginative distortion: the odd group, F, 1, L, P, N and-the ultimate alphabetical sequence T, U, V, W,

Y…” Y, Z.

And once in a sort of geometrical trance or ecstasy which he was never able to repeat, he discovered five solutions in less than an hour. Newton and

Einstein and Chen-tsu could have felt no greater kinship with the gods of mathematics in their own moments of truth…. It did not take him long to realize, without any prompting from Grandma, that it might. also be possible to arrange the pieces in other shapes besides the six-by-ten rectangle. In theory, at least, the twelve pentominoes could exactly cover rectangles with sides of five-by-twelve units, four-by-fifteen units, and even the narrow strip only three units wide and twenty long.

Without too much effort, he found several examples of the five-by twelve and four-by-fifteen rectangles. Then he spent a frustrating week, trying to align the dozen pieces into a perfect three-by-twenty strip. Again and again he produced shorter rectangles, but always there were a few pieces left over, and at last he decided that this shape was impossible.

Defeated, he went back to Grandma-and received another surprise.

“I’m glad you made the effort,” she said. “Generalizing–exploring every possibility-is what mathematics is all about. But you’re wrong. It can be done. There are just two solutions; and if you find one, you’ll also have the other.”

Encouraged, Duncan continued the hunt with renewed vigor. After another week, he began to realize them.agnitude of the problem. The number of distinct ways in which a mere twelve objects could be laid out essentially in a straight line, when one also allowed for the fact that most of them could assume at least four different orientations,

was staggering. Once again, he appealed to Grandma, pointing out the unfairness of the odds. If there were only two solutions, bow long would it take to find them?

“I’ll tell you,” she said. “If you were a brainless computer, and put down the pieces at the rate of one a second in every possible, way, you could run through the whole set in”—she paused for effect–~‘rather more than six million, million years.”

Earth years or Titan years? thought the appalled Duncan. Not that it really mattered … “But you aren’t a brainless computer,” continued Grandma. “You can see at a glance whole categories that won’t fit into the pattern, so you don’t have to bother about them. Try again….”

Duncan obeyed, though without much enthusiasm or success. And then he had a brilliant idea.

Karl was interested, and accepted the challenge at once. He took the set of pentominoes, and that was the last Duncan heard of him for several hours.

Then he called back, looking a little flustered.

“Are you sure it can be done?” he demanded.

“Absolutely. In fact, there are two solutions. Haven’t you found even one?

I thought you were good in mathematics.”

“So I am. That’s why I know how tough the job is. There are over a quadrillion possible arrangements to be checked.”

“How do you work that out?” asked Duncan, delighted to discover something that had baffled his friend.

Karl looked at a piece of paper covered with sketches and numbers.

“Well, excluding forbidden positions, and allowing for symmetry and rotation, it comes to factorial twelve times two to the twenty-first-you wouldn’t understand why! That’s quite a number; here it is.”

He held up a sheet on which he had written, in large figures, the imposing array of digits:

1 004 539 160 000000

Duncan looked at the number with satisfaction; he did not doubt Karl’s

arithmetic. “So you’ve given up.”

“NO! I’m just telling you how hard it is.” And Karl, looking grimly determined, switched off.

The next day, Duncan had one of the biggest surprises of his young life. A bleary-eyed Karl, who had obviously not slept since their last conversation, appeared on his screen.

“Here it is,” he said, exhaustion and triumph competing in his voice.

Duncan could hardly believe his eyes; he had been convinced that the odds against success were impossibly great. But there was the narrow rectangular strip, only three squares wide and twenty long, formed from the complete set of twelve pieces…. With fingers that trembled slightly from fatigue, Karl took the two end sections and switched them around, leaving the center portion of the puzzle untouched.

“And here’s the second solution,” he said. “Now I’m going to bed. Good night-or good morning, if that’s what it is.”

For a long time, a very chastened Duncan sat staring at the blank screen.

He did not yet understand what had happened. He only knew that Karl had won against all reasonable expectations.

It was not that Duncan really minded; he loved Karl too much to resent his little victory, and indeed was capable of rejoicing in his friend’s triumphs even when they were at his own expense. But there was something strange here, something almost magical.

It was Duncan’s first glimpse of the power of intuition, and the mind’s mysterious ability to go beyond the available facts and to short-circuit the process of logic. In a few hours, Karl had completed a search that should have required trillions of operations and would have tied up the fastest computer in existence for an appreciable number of seconds.

One day, Duncan would realize that all men had such powers, but might use them only once in a lifetime. In Karl, the gift was exceptionally well developed; from that moment onward, Duncan had learned to take

seriously even his most outrageous speculations. That was twenty years ago; whatever had happened to that little set of plastic figures? He could not remember when he had last seen it.

But here it was again, reincarnated in colored minerals-the peculiar rose-tinted granite from the Galileo Hills, the obsidian of the Huygens

Plateau, the pseudo marble of the Herschel Escarpment. And there—it was unbelievable, but doubt was impossible in such a matter-was the rarest and most mysterious of all the gemstones found on this world. The X of the puzzle was made of Titanite itself; no one could ever mistake that blue-black sheen with its fugitive flecks of gold. It was the largest piece that Duncan had ever seen, and he could not even guess at its value.

“I don’t know what to say,” he stammered. “It’s beautiful-I’ve never seen anything like it.”

He put his arms around Grandma’s thin shoulders -and found, to his distress, that they were quivering uncontrollably. He held her gently until the shaking stopped, knowing that there were no words for such moments, and realizing as never before that he was the last love of her empty life, and he was leaving her to her memories.

CHILDREN OF THE CORRIDORS

There was a sense of sadness and finality about almost everything that he did in these last days. Sometimes it puzzled Duncan; he should be excited, anticipating the great adventure that only a handful of men on his world could ever share. And though he had never before been out of touch with his friends and family for more than a few hours, he was certain that a year’s absence would pass swiftly enough, among the

wonders and distractions of Earth. So why this melancholy? If he was saying farewell to the things of his youth, it was only for a little while, and he would appreciate them all the more when he returned…. When he returned. That, of course, was the heart of the problem. In a real sense, the Duncan Makenzie who was now leaving Titan would never return; indeed, that was the purpose of the exercise. Like Colin thirty years ago, and Malcolm forty years before that, he was heading sunward in search of knowledge, of power, of maturity-and, above all, of the successor which his own world could never give him. For, of course, being Malcolm’s duplicate, he too carried in his loins the fatal Makenzie gene.

Sooner than he had expected, he had to prepare his family for the new addition. After the usual number of earlier experiments, he had settled down with Marissa four years ago, and he loved her children as much, he was certain, as if they had been his own flesh and blood. Clyde was now six years old, Caroline three. They in their turn appeared to be as fond of

Duncan as of their real fathers, who were now regarded as honorary members of the Clan Makenzie. Much the same thing had happened in Colin’s generation-he had acquired or adopted three families-and in Malcolm’s.

Grandfather had never gone to the trouble of marrying again after Ellen had left him, but he had never lacked company for long. Only a computer could keep track of the comings and goings on the periphery of the clan; it often seemed that most of Titan was related to it in some way or other. One of

Duncan’s major problems now was deciding who would be mortally offended if he failed to say good-bye.

Quite apart from the time factor, he had other rea sons for making as few farewells as possible. Every one of his friends and relatives-as well as almost complete strangers-seemed to have some request for him, some mission they wanted him to carry out as soon as he reached Earth. Or, worse still, there was some essential item (“It won’t be any

trouble”) they wanted him to bring back. Duncan calculated that he would have to charter a special freighter if he aoquiesced to all these demands.

Every job now had to be divided into one of two categories. There were the things that must be done before he left Titan, and those that could be postponed until he was aboard ship. The latter included his studies of current terrestrial affairs, which kept slipping despite ColWs increasingly frantic attempts to update him

Extricating himself from his official duties was also no easy task, and

Duncan realized that in a few more years it would be well-nigh impossible

He was getting involved in too many things, though that was a matter of deliberate family policy. More than once he had complained that his title of Special Assistant to the Chief Administrator gave him responsibility without power. To this, Chief Administrator Colin had retorted: “Do you know what power means in our society? Giving orders to people who carry them out only it and when they feel like it.”

This was, of course, a gross libel on the Titanian bureaucracy, which functioned surprisingly well and with a minimum of red tape. Because all the key individuals knew each other, an immense amount of business got done through direct personal contact. Everyone who had come to Titan had been carefully selected for intelligence and ability, and knew that survival depended upon cooperation. Those who felt like abandoning their social responsibilities first had to practice breathing methane at a hundred below.

One possible embarrassment he had at least been spared. He could hardly leave Titan without saying good-bye to his once closest friend-but, very fortunately, Karl was off-world. Several months ago he had left on one of the shuttles to join a Terran survey ship working its way through the outer moons. Ironically enough, Duncan had envied Karl his chance of seeing some unknown worlds; now it was Karl who would be envious of him.

He could well imagine Karl’s frustration when he heard that Duncan was on his way to Earth. The thought gave him more sadness than pleasure; the

Makenzies, whatever their faults, were not vindictive Yet Duncan could not help wondering how often Karl’s reveries would now turn sunward, and to the moment long ago when their emotions had been irrevocably linked with the mother world.

Duncan was just sixteen, and Karl twenty-one, when the cruise liner Mentor had made her first, and it was widely hoped only, rendezvous with Titan.

She was a converted fusion-drive freighter-slow but economical, provided adequate supplies of hydrogen could be picked up at strategic points.

Mentor had stopped at Titan for her final refueling, on the last leg of a grand tour that had taken her to Mars, Ganymede, Europa, Pallas, and

Iapetus, and had included flybys of Mercury and Eros. As soon as she had loaded some fifteen thousand tons of hydrogen, her exhausted crew planned to head back to Earth on the fastest orbit they could compute, if possible after marooning all the passengers.

The cruise must have seemed a good idea when a consortium of Terran universities had planned it several years earlier. And so indeed it had turned out, in the long run, for Mentor graduates had since proved their worth throughout the Solar System. But when the ship staggered into her parking orbit, under the command of a prematurely gray captain, the whole enterprise looked like a first-magnitude disaster.

The problems of keeping five hundred young adults entertained and out of mischief on a six-months’ cruise aboard even the largest space liner had not been given sufficient thought; the law professor who had signed on as master-at-arms was later heard to complain bitterly about the complete absence from the ship’s inventory of hypodermic guns and knockout gas. On the other hand, there had been no deaths or serious injuries, only one pregnancy, and everyone had learned a great deal, though not necessarily in the areas that the organizers had intended. The first few weeks, for example, were mostly occupied by experiments in zero-gravity sex, despite warnings that this was an expensive addiction for those compelled to spend most of their lives on planetary

surfaces. Other shipboard activities, it was widely believed, were not quite so harmless. There were reports of tobacco-smoking-not actually illegal, of course, but hardly sensible behaviour when there were so many safe alternatives. Even more alarming were persistent rumors that someone had smuggled an Emotion Amplifier on board Mentor. The so-called joy machines were banned on all planets, except under strict medical control; but there would always be people to whom reality was not good enough, and who would want to try something better.

Notwithstanding the horror stories radioed ahead from other ports of call,

Titan had looked forward to welcoming its young visitors. It was felt that they would add color to the social scene, and help establish some enjoyable contacts with Mother Earth. And anyway, it would be for only a week…. Luckily, no one dreamed that it would be for two months. This was not

Mentor’s fault; Titan had only itself to blame.

When Mentor fell into her parking orbit, Earth and Titan were involved in one of their periodical wrangles over the price of hydrogen, FOB. Zero

Gravitational Potential (Solar Reference). The proposed 15 percent rise, screamed the Terrans, would cause the collapse of interplanetary commerce.

Anything under 10 percent, swore the Titanians, would result in their instant bankruptcy and would make it impossible for them to import any of the expensive items Earth was always trying to sell. To any historian of economics, the whole debate was boringly familiar.

Unable to get a firm quotation, Mentor was stranded in orbit with empty fuel tanks. At first, her captain was not too unhappy; he and the crew could do with the rest, now that the passengers had shuttled down to Titan and had fanned out all over the face of the hapless satellite. But one week stretched into two, then three, then a month. By that time, Titan was ready to settle on almost any terms; unfortunately, Mentor had now missed her optimum trajectories, and it would be another

four weeks before the next launch window opened. Meanwhile, the five hundred guests were enjoying themselves, usually much more than their hosts.

But to the younger Titanians, it was an exciting time which they would remember all their lives. On a small world where everyone knew everybody else, half a thousand fascinating strangers had arrived, full of tales, many of them quite true, about the wonders of Earth. Here were men and women, barely into their twenties, who had seen forests and prairies and oceans of liquid water, who had strolled unprotected under an open sky beneath a sun whose heat could actually be felt…. This very contrast in backgrounds, however, was a possible source of danger. The Terrans could not be allowed to go wandering around by themselves, even inside the habitats. They had to have escorts, preferably responsible people not too far from their own age group, to see that they did not inadvertently kill either themselves or their hosts.

Naturally, there were times when they resented this well-intentioned supervision, and even tried to escape from it. One group succeeded; it was very lucky, and suffered no more than a few searing whiffs of ammonia.

Damage was so slight that the foolish adventurers required only routine lung transplants, but after this exploit there was no more serious trouble.

There were plenty of other problems. The sheer mechanics of absorbing five hundred visitors was a challenge to a society where living standards were still somewhat Spartan, and accommodation limited. At first, all the unexpected guests were housed in the complex of corridors left by an abandoned i i g operation, hastily converted into dormitories. Then, as quickly as arrangements could be made, they were farmed out-like refugees from some bombed city in an ancient war-to any households that were able to cope with them. At this stage, there were still many willing volunteers, among them Colin and Sheela Makenzie.

The apartment was lonely, now that Duncan’s pseudo sibling Glynn had left home to work on the other side of Titan; Sheela’s other child,

Yuri, had been gone for a decade. Though Number 402, Second Level, Meridian Park was hardly spacious by Terran standards,

Assistant Administrator Colin Makenzie, as he was then, had selected one of the homeless wafes for temporary adoption.

And so Calindy had come into Duncan’s life-and into Karl’s.

THE FATAL GIFT

Catherine Linden Ellerman had celebrated her twenty-first birthday just before Mentor reached Saturn. By all accounts, it had been a memorable party, giving the final silvery gloss to the captain’s remaining hairs.

Calindy would have sailed through untouched; next to her beauty, that was her most outstanding characteristic. In the midst of chao seven chaos that she herself had generated-she was the calm center of the storm.

With a self-possession far beyond her years, she seemed to young Duncan the very embodiment of Terran culture and sophistidation. He could smile wryly, one and a half decades later, at his boyish naievete but it was not wholly unfounded. By any standards, Calindy was a remarkable phenomenon.

Duncan knew, of course, that all Terrans were rich. (How could it be otherwise, when each was the heir to a hundred thousand generations?) But he was overawed ‘by Calindy’s display of jewels and silks, never realizing that she had a limited wardrobe which she varied with consummate skill.

Most impressive of all was a stunningly beautiful coat of golden fur-the only one ever seen on Titan-made from the skins of an animal called a mink.

That was typical of Calindy; no one else would have dreamed of taking a fur coat aboard a spaceship. And she had not done so—as malicious

rumor pretended-because she had heard it was cold out around Saturn. She was much too intelligent for that kind of stupidity, and knew exactly what she was doing; she had brought her mink simply because it was beautiful.

Perhaps because he could see her only through a mist of adoration, Duncan could never visualize her, in later years, as an actual person. When he thought of Calindy, and tried to conjure up her image, he did pot see the real girl, but always his only replica of her, in one of the bubble stereos that had become popular in the ‘50’s.

How many thousands of times he had taken that apparently solid, yet almost weightless sphere in his hands, shaken it gently, and thus activated the five second loo pI Through the subtle magic of organized gas molecules, each releasing its programmed quantum of light, Calindy’s face would appear out of the swirling mists-tiny, yet perfect in form and color. At first she would be in proffle; then she would turn and suddenly-Duncan could never be sure of the moment when it arrived-there would be the faint smile that only

Leonardo could have captured in an earlier age. She did not seem to be smiling at him, but at someone over his shoulder. The impression was so strong that more than once Duncan had looked back, startled, to see who was standing behind him.

Then the image would fade, the bubble would become opaque, and he would have to wait five minutes before the system recharged itself. It did not matter; he had only to close his eyes and he could still see the perfect oval face, the delicate ivory skin, the lustrous black hair gathered up into a toque and held in place by a silver comb that had belonged to a

Spanish princess, when Columbus was a child. Calindy liked playing roles, though she took none of them too seriously, and Carmen was one of her favorites. when she entered the Makenzie household, however, she was the exiled aristocrat, graciously accepting the hospitality of kindly provincials, with what few family heirlooms she had been able to save from the

Revolution. As this impressed no one except Duncan, she quickly became the studious anthropologist, taking notes for her thesis on the quaint

habits of 46 primitive societies. This role was at least partly genuine, for Calindy was really interested in differing life styles; and by some definitions, Titan could indeed be classed as primitive—or, at least, undeveloped.

Thus the supposedly unshockable Terrans were genuinely horrified at encountering families with three—and even fourl–children on Titan. The twentieth century’s millions of skeleton babies still haunted the conscience of the world, and such tragic but understandable excesses as the “Breeder Lynching” campaign, not to mention the burning of the Vatican, had left permanent scars on the human psyche. Duncan could still remember

Calindy’s expression when she encountered her first family of six: outrage contended with curiosity, until both were moderated by Terran good manners.

He had patiently explained the facts of life to her, pointing out that there was nothing eternally sacred about the dogma of Zero Growth, and that

Titan really needed to double its population every fifty years. Eventually she appreciated this logically, but she had never been able to accept it emotionally. And it was emotion that provided the driving force of

Calindy’s life; her will and beauty and intelligence were merely its servants.

For a young Terran, she was not promiscuous. She once told Duncan-and he believed her-that she never had more than two lovers at a time. On Titan, to Duncan’s considerable distress, she had only one.

Even if the Helmers and Makenzies had not been related through Grandma

Ellen, it was inevitable that she would have met Karl, at one of the countless concerts and parties and dances arranged for Mentor’s castaways.

So Duncan could not really blame himself for introducing them; it would have made no difference in the end. Yet even so, he would always wonder…. Karl was then almost twenty-two-a year older than Calindy, though far less experienced. He still possessed the slightly overmuscled build of the native born Terran, but had adapted so well to the lower gravity that he moved more gracefully than most men who had spent their entire lives on

Titan. He seemed to possess the secret of power without clumsiness. And in a quite literal sense, he was the Golden Boy of his generation.

Though he pretended to hate the phrase, Duncan knew that he was secretly proud of the title someone had given him in his teens: “The boy with hair like the sun.” The description could only have been coined by a visitor from Earth. No Titanian would have thought of it-but everyone agreed that it was completely appropriate. For Karl Helmer was one of those men upon whom, for their own amusement, the Gods had bestowed the fatal gift of beauty.

Only years later, and partly thanks to Colin, did Duncan begin to understand all the nuances of the affair. Soon after his twenty-third birthday, the Makenzies received the last Star Day card that Calindy ever sent them.

“I still don’t know if I made a mistake,” Colin said ruefully as he fingered the bright rectangle of paper that had carried its conventional greetings halfway across the Solar System. “But it seemed a good idea at the time.”

“Well, I don’t think it did any harm, in the long run. tv

Cohn looked at him strangely.

“I wonder. Anyway, it certainly didn’t turn out as I expected.”

“And what did you expect?”

It was sometimes a great advantage, and sometimes downright embarrassing, to have a father who was also your thirty-year-older identical twin. He knew all the mistakes you were going to make, because he had made them already. It was impossible to conceal any secrets from him, because his thought processes were virtually the same. In such a situation, the only policy that made any sense was complete honesty, as far as that could be achieved by human beings.