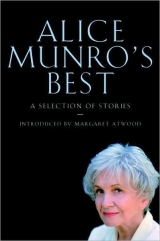

Текст книги "Alice Munro's Best"

Автор книги: Alice Munro

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

AUNT BERYL said not to call her Aunt. “I’m not used to being anybody’s aunt, honey. I’m not even anybody’s momma. I’m just me. Call me Beryl.”

Beryl had started out as a stenographer, and now she had her own typing and bookkeeping business, which employed many girls. She had arrived with a man friend, whose name was Mr. Florence. Her letter had said that she would be getting a ride with a friend, but she hadn’t said whether the friend would be staying or going on. She hadn’t even said if it was a man or a woman.

Mr. Florence was staying. He was a tall, thin man with a long, tanned face, very light-colored eyes, and a way of twitching the corner of his mouth that might have been a smile.

He was the one who got to sleep in the room that my mother and I had papered, because he was the stranger, and a man. Beryl had to sleep with me. At first we thought that Mr. Florence was quite rude, because he wasn’t used to our way of talking and we weren’t used to his. The first morning, my father said to Mr. Florence, “Well, I hope you got some kind of a sleep on that old bed in there.” (The spare-room bed was heavenly, with a feather tick.) This was Mr. Florence’s cue to say that he had never slept better.

Mr. Florence twitched. He said, “I slept on worse.”

His favorite place to be was in his car. His car was a royal-blue Chrysler, from the first batch turned out after the war. Inside it, the upholstery and floor covering and roof and door padding were all pearl gray. Mr. Florence kept the names of those colors in mind and corrected you if you said just “blue” or “gray.”

“Mouse skin is what it looks like to me,” said Beryl rambunctiously “I tell him it’s just mouse skin!”

The car was parked at the side of the house, under the locust trees. Mr. Florence sat inside with the windows rolled up, smoking, in the rich new-car smell.

“I’m afraid we’re not doing much to entertain your friend,” my mother said.

“I wouldn’t worry about him,” said Beryl. She always spoke about Mr. Florence as if there was a joke about him that only she appreciated. I wondered long afterward if he had a bottle in the glove compartment and took a nip from time to time to keep his spirits up. He kept his hat on.

Beryl herself was being entertained enough for two. Instead of staying in the house and talking to my mother, as a lady visitor usually did, she demanded to be shown everything there was to see on a farm. She said that I was to take her around and explain things, and see that she didn’t fall into any manure piles.

I didn’t know what to show. I took Beryl to the icehouse, where chunks of ice the size of dresser drawers, or bigger, lay buried in saw dust. Every few days, my father would chop off a piece of ice and carry it to the kitchen, where it melted in a tin-lined box and cooled the milk and butter.

Beryl said she had never had any idea ice came in pieces that big. She seemed intent on finding things strange, or horrible, or funny.

“Where in the world do you get ice that big?”

I couldn’t tell if that was a joke.

“Off of the lake,” I said.

“Off of the lake! Do you have lakes up here that have ice on them all summer?”

I told her how my father cut the ice on the lake every winter and hauled it home, and buried it in sawdust, and that kept it from melting.

Beryl said, “That’s amazing!”

“Well, it melts a little,” I said. I was deeply disappointed in Beryl.

“That’s really amazing.”

Beryl went along when I went to get the cows. A scarecrow in white slacks (this was what my father called her afterward), with a white sun hat tied under her chin by a flaunting red ribbon. Her fingernails and toenails – she wore sandals – were painted to match the ribbon. She wore the small, dark sunglasses people wore at that time. (Not the people I knew – they didn’t own sunglasses.) She had a big red mouth, a loud laugh, hair of an unnatural color and a high gloss, like cherry wood. She was so noisy and shiny, so glamorously got up, that it was hard to tell whether she was good-looking, or happy, or anything.

We didn’t have any conversation along the cowpath, because Beryl kept her distance from the cows and was busy watching where she stepped. Once I had them all tied in their stalls, she came closer. She lit a cigarette. Nobody smoked in the barn. My father and other farmers chewed tobacco there instead. I didn’t see how I could ask Beryl to chew tobacco.

“Can you get the milk out of them or does your father have to?” Beryl said. “Is it hard to do?”

I pulled some milk down through the cow’s teat. One of the barn cats came over and waited. I shot a thin stream into its mouth. The cat and I were both showing off.

“Doesn’t that hurt?” said Beryl. “Think if it was you.”

I had never thought of a cow’s teat as corresponding to any part of myself, and was shaken by this indecency. In fact, I could never grasp a warm, warty teat in such a firm and casual way again.

* * *

BERYL SLEPT IN a peach-colored rayon nightgown trimmed with écru lace. She had a robe to match. She was just as careful about the word écru as Mr. Florence was about his royal blue and pearl gray.

I managed to get undressed and put on my nightgown without any part of me being exposed at any time. An awkward business. I left my underpants on, and hoped that Beryl had done the same. The idea of sharing my bed with a grownup was a torment to me. But I did get to see the contents of what Beryl called her beauty kit. Hand-painted glass jars contained puffs of cotton wool, talcum powder, milky lotion, ice-blue astringent. Little pots of red and mauve rouge – rather greasy-looking. Blue and black pencils. Emery boards, a pumice stone, nail polish with an overpowering smell of bananas, face powder in a celluloid box shaped like a shell, with the name of a dessert – Apricot Delight.

I had heated some water on the coal-oil stove we used in summertime. Beryl scrubbed her face clean, and there was such a change that I almost expected to see makeup lying in strips in the washbowl, like the old wallpaper we had soaked and peeled. Beryl’s skin was pale now, covered with fine cracks, rather like the shiny mud at the bottom of puddles drying up in early summer.

“Look what happened to my skin,” she said. “Dieting. I weighed a hundred and sixty-nine pounds once, I took it off too fast and my face fell in on me. Now I’ve got this cream, though. It’s made from a secret formula and you can’t even buy it commercially. Smell it. See, it doesn’t smell all perfumy. It smells serious.”

She was patting the cream on her face with puffs of cotton wool, patting away until there was nothing to be seen on the surface.

“It smells like lard,” I said.

“Christ Almighty, I hope I haven’t been paying that kind of money to rub lard on my face. Don’t tell your mother I swear.”

She poured clean water into the drinking glass and wet her comb, then combed her hair wet and twisted each strand round her finger, clamping the twisted strand to her head with two crossed pins. I would be doing the same myself, a couple of years later.

“Always do your hair wet, else it’s no good doing it up at all,” Beryl said. “And always roll it under even if you want it to flip up. See?”

When I was doing my hair up – as I did for years – I sometimes thought of this, and thought that of all the pieces of advice people had given me, this was the one I had followed most carefully.

We put the lamp out and got into bed, and Beryl said, “I never knew it could get so dark. I’ve never known a dark that was as dark as this.” She was whispering. I was slow to understand that she was comparing country nights to city nights, and I wondered if the darkness in Netterfield County could really be greater than that in California.

“Honey?” whispered Beryl. “Are there any animals outside?”

“Cows,” I said.

“Yes, but wild animals? Are there bears?”

“Yes,” I said. My father had once found bear tracks and droppings in the bush, and the apples had all been torn off a wild apple tree. That was years ago, when he was a young man.

Beryl moaned and giggled. “Think if Mr. Florence had to go out in the night and he ran into a bear!”

NEXT DAY WAS Sunday. Beryl and Mr. Florence drove my brothers and me to Sunday school in the Chrysler. That was at ten o’clock in the morning. They came back at eleven to bring my parents to church.

“Hop in,” Beryl said to me. “You too,” she said to the boys. “We’re going for a drive.”

Beryl was dressed up in a satiny ivory dress with red dots, and a red-lined frill over the hips, and red high-heeled shoes. Mr. Florence wore a pale-blue summer suit.

“Aren’t you going to church?” I said. That was what people dressed up for, in my experience.

Beryl laughed. “Honey, this isn’t Mr. Florence’s kind of religion.”

I was used to going straight from Sunday school into church, and sitting for another hour and a half. In summer, the open windows let in the cedary smell of the graveyard and the occasional, almost sacrilegious sound of a car swooshing by on the road. Today we spent this time driving through country I had never seen before. I had never seen it, though it was less than twenty miles from home. Our truck went to the cheese factory, to church, and to town on Saturday nights. The nearest thing to a drive was when it went to the dump. I had seen the near end of Bell’s Lake, because that was where my father cut the ice in winter. You couldn’t get close to it in summer; the shoreline was all choked up with bulrushes. I had thought that the other end of the lake would look pretty much the same, but when we drove there today, I saw cottages, docks and boats, dark water reflecting the trees. All this and I hadn’t known about it. This too was Bell’s Lake. I was glad to have seen it at last, but in some way not altogether glad of the surprise.

Finally, a white frame building appeared, with verandas and potted flowers, and some twinkling poplar trees in front. The Wildwood Inn. Today the same building is covered with stucco and done up with Tudor beams and called the Hideaway. The poplar trees have been cut down for a parking lot.

On the way back to the church to pick up my parents, Mr. Florence turned in to the farm next to ours, which belonged to the McAllisters. The McAllisters were Catholics. Our two families were neighborly but not close.

“Come on, boys, out you get,” said Beryl to my brothers. “Not you,” she said to me. “You stay put.” She herded the little boys up to the porch, where some McAllisters were watching. They were in their raggedy home clothes, because their church, or Mass, or whatever it was, got out early. Mrs. McAllister came out and stood listening, rather dumbfounded, to Beryl’s laughing talk.

Beryl came back to the car by herself. “There,” she said. “They’re going to play with the neighbor children.”

Play with McAllisters? Besides being Catholics, all but the baby were girls.

“They’ve still got their good clothes on,” I said.

“So what? Can’t they have a good time with their good clothes on? I do!”

My parents were taken by surprise as well. Beryl got out and told my father he was to ride in the front seat, for the legroom. She got into the back, with my mother and me. Mr. Florence turned again onto the Bell’s Lake road, and Beryl announced that we were all going to the Wildwood Inn for dinner.

“You’re all dressed up, why not take advantage?” she said. “We dropped the boys off with your neighbors. I thought they might be too young to appreciate it. The neighbors were happy to have them.” She said with a further emphasis that it was to be their treat. Hers and Mr. Florence’s.

“Well, now,” said my father. He probably didn’t have five dollars in his pocket. “Well, now. I wonder do they let the farmers in?”

He made various jokes along this line. In the hotel dining room, which was all in white – white tablecloths, white painted chairs – with sweating glass water pitchers and high, whirring fans, he picked up a table napkin the size of a diaper and spoke to me in a loud whisper, “Can you tell me what to do with this thing? Can I put it on my head to keep the draft off?”

Of course he had eaten in hotel dining rooms before. He knew about table napkins and pie forks. And my mother knew – she wasn’t even a country woman, to begin with. Nevertheless this was a huge event. Not exactly a pleasure – as Beryl must have meant it to be – but a huge, unsettling event. Eating a meal in public, only a few miles from home, eating in a big room full of people you didn’t know, the food served by a stranger, a snippy-looking girl who was probably a college student working at a summer job.

“I’d like the rooster,” my father said. “How long has he been in the pot?” It was only good manners, as he knew it, to joke with people who waited on him.

“Beg your pardon?” the girl said.

“Roast chicken,” said Beryl. “Is that okay for everybody?”

Mr. Florence was looking gloomy. Perhaps he didn’t care for jokes when it was his money that was being spent. Perhaps he had counted on something better than ice water to fill up the glasses.

The waitress put down a dish of celery and olives, and my mother said, “Just a minute while I give thanks.” She bowed her head and said quietly but audibly, “Lord, bless this food to our use, and us to Thy service, for Christ’s sake. Amen.” Refreshed, she sat up straight and passed the dish to me, saying, “Mind the olives. There’s stones in them.”

Beryl was smiling around at the room.

The waitress came back with a basket of rolls.

“Parker House!” Beryl leaned over and breathed in their smell. “Eat them while they’re hot enough to melt the butter!”

Mr. Florence twitched, and peered into the butter dish. “Is that what this is – butter? I thought it was Shirley Temple’s curls.”

His face was hardly less gloomy than before, but it was a joke, and his making it seemed to convey to us something of the very thing that had just been publicly asked for – a blessing.

“When he says something funny,” said Beryl – who often referred to Mr. Florence as “he” even when he was right there – “you notice how he always keeps a straight face? That reminds me of Mama. I mean of our mama, Marietta’s and mine. Daddy, when he made a joke you could see it coming a mile away – he couldn’t keep it off his face – but Mama was another story. She could look so sour. But she could joke on her deathbed. In fact, she did that very thing. Marietta, remember when she was in bed in the front room the spring before she died?”

“I remember she was in bed in that room,” my mother said. “Yes.”

“Well, Daddy came in and she was lying there in her clean nightgown, with the covers off, because the German lady from next door had just been helping her take a wash, and she was still there tidying up the bed. So Daddy wanted to be cheerful, and he said, ‘Spring must be coming. I saw a crow today.’ This must have been in March. And Mama said quick as a shot, ‘Well, you better cover me up then, before it looks in that window and gets any ideas!’ The German lady – Daddy said she just about dropped the basin. Because it was true, Mama was skin and bones; she was dying. But she could joke.”

Mr. Florence said, “Might as well when there’s no use to cry.”

“But she could carry a joke too far, Mama could. One time, one time, she wanted to give Daddy a scare. He was supposed to be interested in some girl that kept coming around to the works. Well, he was a big good-looking man. So Mama said, ‘Well, I’ll just do away with myself, and you can get on with her and see how you like it when I come back and haunt you.’ He told her not to be so stupid, and he went off downtown. And Mama went out to the barn and climbed on a chair and put a rope around her neck. Didn’t she, Marietta? Marietta went looking for her and she found her like that!”

My mother bent her head and put her hands in her lap, almost as if she was getting ready to say another grace.

“Daddy told me all about it, but I can remember anyway. I remember Marietta tearing off down the hill in her nightie, and I guess the German lady saw her go, and she came out and was looking for Mama, and somehow we all ended up in the barn – me too, and some kids I was playing with – and there was Mama up on a chair preparing to give Daddy the fright of his life. She’d sent Marietta after him. And the German lady starts wailing, ‘Oh, missus, come down missus, think of your little kindren’ – ‘kindren’ is the German for ‘children’ – ‘think of your kindren,’ and so on. Until it was me standing there – I was just a little squirt, but I was the one noticed that rope. My eyes followed that rope up and up and I saw it was just hanging over the beam, just flung there – it wasn’t tied at all! Marietta hadn’t noticed that, the German lady hadn’t noticed it. But I just spoke up and said, ‘Mama, how are you going to manage to hang yourself without that rope tied around the beam?’”

Mr. Florence said, “That’d be a tough one.”

“I spoiled her game. The German lady made coffee and we went over there and had a few treats, and, Marietta, you couldn’t find Daddy after all, could you? You could hear Marietta howling, coming up the hill, a block away.”

“Natural for her to be upset,” my father said.

“Sure it was. Mama went too far.”

“She meant it,” my mother said. “She meant it more than you give her credit for.”

“She meant to get a rise out of Daddy. That was their whole life together. He always said she was a hard woman to live with, but she had a lot of character. I believe he missed that, with Gladys.”

“I wouldn’t know,” my mother said, in that particularly steady voice with which she always spoke of her father. “What he did say or didn’t say.”

“People are dead now,” said my father. “It isn’t up to us to judge.”

“I know,” said Beryl. “I know Marietta’s always had a different view.”

My mother looked at Mr. Florence and smiled quite easily and radiantly. “I’m sure you don’t know what to make of all these family matters.”

The one time that I visited Beryl, when Beryl was an old woman, all knobby and twisted up with arthritis, Beryl said, “Marietta got all Daddy’s looks. And she never did a thing with herself. Remember her wearing that old navy-blue crêpe dress when we went to the hotel that time? Of course, I know it was probably all she had, but did it have to be all she had? You know, I was scared of her somehow. I couldn’t stay in a room alone with her. But she had outstanding looks.” Trying to remember an occasion when I had noticed my mother’s looks, I thought of the time in the hotel, my mother’s pale-olive skin against the heavy white, coiled hair, her open, handsome face smiling at Mr. Florence – as if he was the one to be forgiven.

I DIDN’T HAVE a problem right away with Beryl’s story. For one thing, I was hungry and greedy, and a lot of my attention went to the roast chicken and gravy and mashed potatoes laid on the plate with an ice-cream scoop and the bright diced vegetables out of a can, which I thought much superior to those fresh from the garden. For dessert, I had a butterscotch sundae, an agonizing choice over chocolate. The others had plain vanilla ice cream.

Why shouldn’t Beryl’s version of the same event be different from my mother’s? Beryl was strange in every way – everything about her was slanted, seen from a new angle. It was my mother’s version that held, for a time. It absorbed Beryl’s story, closed over it. But Beryl’s story didn’t vanish; it stayed sealed off for years, but it wasn’t gone. It was like the knowledge of that hotel and dining room. I knew about it now, though I didn’t think of it as a place to go back to. And indeed, without Beryl’s or Mr. Florence’s money, I couldn’t. But I knew it was there.

The next time I was in the Wildwood Inn, in fact, was after I was married. The Lions Club had a banquet and dance there. The man I had married, Dan Casey, was a Lion. You could get a drink there by that time. Dan Casey wouldn’t have gone anywhere you couldn’t. Then the place was remodelled into the Hideaway, and now they have strippers every night but Sunday. On Thursday nights, they have a male stripper. I go there with people from the real-estate office to celebrate birthdays or other big events.

THE FARM WAS sold for five thousand dollars in 1965. A man from Toronto bought it, for a hobby farm or just an investment. After a couple of years, he rented it to a commune. They stayed there, different people drifting on and off, for a dozen years or so. They raised goats and sold the milk to the health-food store that had opened up in town. They painted a rainbow across the side of the barn that faced the road. They hung tie-dyed sheets over the windows, and let the long grass and flowering weeds reclaim the yard. My parents had finally got electricity in, but these people didn’t use it. They preferred oil lamps and the woodstove, and taking their dirty clothes to town. People said they wouldn’t know how to handle lamps or wood fires, and they would burn the place down. But they didn’t. In fact, they didn’t manage badly. They kept the house and barn in some sort of repair and they worked a big garden. They even dusted their potatoes against blight – though I heard that there was some sort of row about this and some of the stricter members left. The place actually looked a lot better than many of the farms round about that were still in the hands of the original families. The McAllister son had started a wrecking business on their place. My own brothers were long gone.

I knew I was not being reasonable, but I had the feeling that I’d rather see the farm suffer outright neglect – I’d sooner see it in the hands of hoodlums and scroungers – than see that rainbow on the barn, and some letters that looked Egyptian painted on the wall of the house. They seemed a mockery. I even disliked the sight of those people when they came to town – the men with their hair in ponytails, and with holes in their overalls that I believed were cut on purpose, and the women with long hair and no makeup and their meek, superior expressions. What do you know about life, I felt like asking them. What makes you think you can come here and mock my father and mother and their life and their poverty? But when I thought of the rainbow and those letters, I knew they weren’t trying to mock or imitate my parents’ life. They had displaced that life, hardly knowing it existed. They had set up in its place these beliefs and customs of their own, which I hoped would fail them.

That happened, more or less. The commune disintegrated. The goats disappeared. Some of the women moved to town, cut their hair, put on makeup, and got jobs as waitresses or cashiers to support their children. The Toronto man put the place up for sale, and after about a year it was sold for more than ten times what he had paid for it. A young couple from Ottawa bought it. They have painted the outside a pale gray with oyster trim, and have put in skylights and a handsome front door with carriage lamps on either side. Inside, they’ve changed it around so much that I’ve been told I’d never recognize it.

I did get in once, before this happened, during the year that the house was empty and for sale. The company I work for was handling it, and I had a key, though the house was being shown by another agent. I let myself in on a Sunday afternoon. I had a man with me, not a client but a friend – Bob Marks, whom I was seeing a lot at the time.

“This is that hippie place,” Bob Marks said when I stopped the car. “I’ve been by here before.”

He was a lawyer, a Catholic, separated from his wife. He thought he wanted to settle down and start up a practice here in town. But there already was one Catholic lawyer. Business was slow. A couple of times a week, Bob Marks would be fairly drunk before supper.

“It’s more than that,” I said. “It’s where I was born. Where I grew up.” We walked through the weeds, and I unlocked the door.

He said that he had thought, from the way I talked, that it would be farther out.

“It seemed farther then.”

All the rooms were bare, and the floors swept clean. The woodwork was freshly painted – I was surprised to see no smudges on the glass. Some new panes, some old wavy ones. Some of the walls had been stripped of their paper and painted. A wall in the kitchen was painted a deep blue, with an enormous dove on it. On a wall in the front room, giant sunflowers appeared, and a butterfly of almost the same size.

Bob Marks whistled. “Somebody was an artist.”

“If that’s what you want to call it,” I said, and turned back to the kitchen. The same woodstove was there. “My mother once burned up three thousand dollars,” I said. “She burned three thousand dollars in that stove.”

He whistled again, differently. “What do you mean? She threw in a check?”

“No, no. It was in bills. She did it deliberately. She went into town to the bank and she had them give it all to her, in a shoebox. She brought it home and put it in the stove. She put it in just a few bills at a time, so it wouldn’t make too big a blaze. My father stood and watched her.”

“What are you talking about?” said Bob Marks. “I thought you were so poor.”

“We were. We were very poor.”

“So how come she had three thousand dollars? That would be like thirty thousand today. Easily. More than thirty thousand today.”

“It was her legacy,” I said. “It was what she got from her father. Her father died in Seattle and left her three thousand dollars, and she burned it up because she hated him. She didn’t want his money. She hated him.”

“That’s a lot of hate,” Bob Marks said.

“That isn’t the point. Her hating him, or whether he was bad enough for her to have a right to hate him. Not likely he was. That isn’t the point.”

“Money,” he said. “Money’s always the point.”

“No. My father letting her do it is the point. To me it is. My father stood and watched and he never protested. If anybody had tried to stop her, he would have protected her. I consider that love.”

“Some people would consider it lunacy.”

I remember that that had been Beryl’s opinion, exactly.

I went into the front room and stared at the butterfly, with its pink-and-orange wings. Then I went into the front bedroom and found two human figures painted on the wall. A man and a woman holding hands and facing straight ahead. They were naked, and larger than life size.

“It reminds me of that John Lennon and Yoko Ono picture,” I said to Bob Marks, who had come in behind me. “That record cover, wasn’t it?” I didn’t want him to think that anything he had said in the kitchen had upset me.

Bob Marks said, “Different color hair.”

That was true. Both figures had yellow hair painted in a solid mass, the way they do it in the comic strips. Horsetails of yellow hair curling over their shoulders and little pigtails of yellow hair decorating their not so private parts. Their skin was a flat beige pink and their eyes a staring blue, the same blue that was on the kitchen wall.

I noticed that they hadn’t quite finished peeling the wallpaper away before making this painting. In the corner, there was some paper left that matched the paper on the other walls – a modernistic design of intersecting pink and gray and mauve bubbles. The man from Toronto must have put that on. The paper underneath hadn’t been stripped off when this new paper went on. I could see an edge of it, the cornflowers on a white ground.

“I guess this was where they carried on their sexual shenanigans,” Bob Marks said, in a tone familiar to me. That thickened, sad, uneasy, but determined tone. The not particularly friendly lust of middle-aged respectable men.

I didn’t say anything. I worked away some of the bubble paper to see more of the cornflowers. Suddenly I hit a loose spot, and ripped away a big swatch of it. But the cornflower paper came too, and a little shower of dried plaster.

“Why is it?” I said. “Just tell me, why is it that no man can mention a place like this without getting around to the subject of sex in about two seconds flat? Just say the words hippie or commune and all you guys can think about is screwing! As if there wasn’t anything at all behind it but orgies and fancy combinations and non-stop screwing! I get so sick of that – it’s all so stupid it just makes me sick!”

IN THE CAR, on the way home from the hotel, we sat as before – the men in the front seat, the women in the back. I was in the middle, Beryl and my mother on either side of me. Their heated bodies pressed against me, through cloth; their smells crowded out the smells of the cedar bush we passed through, and the pockets of bog, where Beryl exclaimed at the water lilies. Beryl smelled of all those things in pots and bottles. My mother smelled of flour and hard soap and the warm crêpe of her good dress and the kerosene she had used to take the spots off.

“A lovely meal,” my mother said. “Thank you, Beryl. Thank you, Mr. Florence.”

“I don’t know who is going to be fit to do the milking,” my father said. “Now that we’ve all ate in such style.”

“Speaking of money,” said Beryl – though nobody actually had been – “do you mind my asking what you did with yours? I put mine in real estate. Real estate in California – you can’t lose. I was thinking you could get an electric stove, so you wouldn’t have to bother with a fire in summer or fool with that coal-oil thing, either one.”

All the other people in the car laughed, even Mr. Florence.

“That’s a good idea, Beryl,” said my father. “We could use it to set things on till we get the electricity.”

“Oh, Lord,” said Beryl. “How stupid can I get?”

“And we don’t actually have the money, either,” my mother said cheerfully, as if she was continuing the joke.

But Beryl spoke sharply. “You wrote me you got it. You got the same as me.”

My father half turned in his seat. “What money are you talking about?” he said. “What’s this money?”

“From Daddy’s will,” Beryl said. “That you got last year. Look, maybe I shouldn’t have asked. If you had to pay something off, that’s still a good use, isn’t it? It doesn’t matter. We’re all family here. Practically.”

“We didn’t have to use it to pay anything off,” my mother said. “I burned it.”