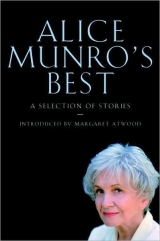

Текст книги "Alice Munro's Best"

Автор книги: Alice Munro

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 37 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

In the spring sunshine she sat, weeping weakly, on a bench by the wall. She was still polite – she apologized for her tears, and never argued with a suggestion or refused to answer a question. But she wept. Weeping had left her eyes raw-edged and dim. Her cardigan – if it was hers – would be buttoned crookedly. She had not got to the stage of leaving her hair unbrushed or her nails uncleaned, but that might come soon.

Kristy said that her muscles were deteriorating, and that if she didn’t improve soon they would put her on a walker.

“But you know once they get a walker they start to depend on it and they never walk much anymore, just get wherever it is they have to go.”

“You’ll have to work at her harder,” she said to Grant. “Try and encourage her.”

But Grant had no luck at that. Fiona seemed to have taken a dislike to him, though she tried to cover it up. Perhaps she was reminded, every time she saw him, of her last minutes with Aubrey, when she had asked him for help and he hadn’t helped her.

He didn’t see much point in mentioning their marriage, now.

She wouldn’t go down the hall to where most of the same people were still playing cards. And she wouldn’t go into the television room or visit the conservatory.

She said that she didn’t like the big screen, it hurt her eyes. And the birds’ noise was irritating and she wished they would turn the fountain off once in a while.

So far as Grant knew, she never looked at the book about Iceland, or at any of the other – surprisingly few – books that she had brought from home. There was a reading room where she would sit down to rest, choosing it probably because there was seldom anybody there, and if he took a book off the shelves she would allow him to read to her. He suspected that she did that because it made his company easier for her – she was able to shut her eyes and sink back into her own grief. Because if she let go of her grief even for a minute it would only hit her harder when she bumped into it again. And sometimes he thought she closed her eyes to hide a look of informed despair that it would not be good for him to see.

So he sat and read to her out of one of these old novels about chaste love, and lost-and-regained fortunes, that could have been the discards of some long-ago village or Sunday school library. There had been no attempt,apparently, to keep the contents of the reading room as up-to-date as most things in the rest of the building.

The covers of the books were soft, almost velvety, with designs of leaves and flowers pressed into them, so that they resembled jewelry boxes or chocolate boxes. That women – he supposed it would be women – could carry home like treasure.

THE SUPERVISOR CALLED him into her office. She said that Fiona was not thriving as they had hoped.

“Her weight is going down even with the supplement. We’re doing all we can for her.”

Grant said that he realized they were.

“The thing is, I’m sure you know, we don’t do any prolonged bed care on the first floor. We do it temporarily if someone isn’t feeling well, but if they get too weak to move around and be responsible we have to consider upstairs.”

He said he didn’t think that Fiona had been in bed that often.

“No. But if she can’t keep up her strength, she will be. Right now she’s borderline.”

He said that he had thought the second floor was for people whose minds were disturbed.

“That too,” she said.

HE HADN’T REMEMBERED anything about Aubrey’s wife except the tartan suit he had seen her wearing in the parking lot. The tails of the jacket had flared open as she bent into the trunk of the car. He had got the impression of a trim waist and wide buttocks.

She was not wearing the tartan suit today. Brown belted slacks and a pink sweater. He was right about the waist – the tight belt showed she made a point of it. It might have been better if she hadn’t, since she bulged out considerably above and below.

She could be ten or twelve years younger than her husband. Her hair was short, curly, artificially reddened. She had blue eyes – a lighter blue than Fiona’s, a flat robin’s-egg or turquoise blue – slanted by a slight puffiness. And a good many wrinkles made more noticeable by a walnut-stain makeup. Or perhaps that was her Florida tan.

He said that he didn’t quite know how to introduce himself.

“I used to see your husband at Meadowlake. I’m a regular visitor there myself.”

“Yes,” said Aubrey’s wife, with an aggressive movement of her chin.

“How is your husband doing?”

The “doing” was added on at the last moment. Normally he would have said, “How is your husband?”

“He’s okay,” she said.

“My wife and he struck up quite a close friendship.”

“I heard about that.”

“So. I wanted to talk to you about something if you had a minute.”

“My husband did not try to start anything with your wife, if that’s what you’re getting at,” she said. “He did not molest her in any way. He isn’t capable of it and he wouldn’t anyway. From what I heard it was the other way round.”

Grant said, “No. That isn’t it at all. I didn’t come here with any complaints about anything.”

“Oh,” she said. “Well, I’m sorry. I thought you did.”

That was all she was going to give by way of apology. And she didn’t sound sorry. She sounded disappointed and confused.

“You better come in, then,” she said. “It’s blowing cold in through the door. It’s not as warm out today as it looks.”

So it was something of a victory for him even to get inside. He hadn’t realized it would be as hard as this. He had expected a different sort of wife. A flustered homebody, pleased by an unexpected visit and flattered by a confidential tone.

She took him past the entrance to the living room, saying, “We’ll have to sit in the kitchen where I can hear Aubrey.” Grant caught sight of two layers of front-window curtains, both blue, one sheer and one silky, a matching blue sofa and a daunting pale carpet, various bright mirrors and ornaments.

Fiona had a word for those sort of swooping curtains – she said it like a joke, though the women she’d picked it up from used it seriously. Any room that Fiona fixed up was bare and bright – she would have been astonished to see so much fancy stuff crowded into such a small space. He could not think what that word was.

From a room off the kitchen – a sort of sunroom, though the blinds were drawn against the afternoon brightness – he could hear the sounds of television.

Aubrey. The answer to Fiona’s prayers sat a few feet away, watching what sounded like a ball game. His wife looked in at him. She said, “You okay?” and partly closed the door.

“You might as well have a cup of coffee,” she said to Grant.

He said, “Thanks.”

“My son got him on the sports channel a year ago Christmas, I don’t know what we’d do without it.”

On the kitchen counters there were all sorts of contrivances and appliances – coffeemaker, food processor, knife sharpener, and some things Grant didn’t know the names or uses of. All looked new and expensive, as if they had just been taken out of their wrappings, or were polished daily.

He thought it might be a good idea to admire things. He admired the coffeemaker she was using and said that he and Fiona had always meant to get one. This was absolutely untrue – Fiona had been devoted to a European contraption that made only two cups at a time.

“They gave us that,” she said. “Our son and his wife. They live in Kamloops. B.C. They send us more stuff than we can handle. It wouldn’t hurt if they would spend the money to come and see us instead.”

Grant said philosophically, “I suppose they’re busy with their own lives.”

“They weren’t too busy to go to Hawaii last winter. You could understand it if we had somebody else in the family, closer at hand. But he’s the only one.”

The coffee being ready, she poured it into two brown-and-green ceramic mugs that she took from the amputated branches of a ceramic tree trunk that sat on the table.

“People do get lonely,” Grant said. He thought he saw his chance now. “If they’re deprived of seeing somebody they care about, they do feel sad. Fiona, for instance. My wife.”

“I thought you said you went and visited her.”

“I do,” he said. “That’s not it.”

Then he took the plunge, going on to make the request he’d come to make. Could she consider taking Aubrey back to Meadowlake maybe just one day a week, for a visit? It was only a drive of a few miles, surely it wouldn’t prove too difficult. Or if she’d like to take the time off – Grant hadn’t thought of this before and was rather dismayed to hear himself suggest it – then he himself could take Aubrey out there, he wouldn’t mind at all. He was sure he could manage it. And she could use a break.

While he talked she moved her closed lips and her hidden tongue as if she was trying to identify some dubious flavor. She brought milk for his coffee, and a plate of ginger cookies.

“Homemade,” she said as she set the plate down. There was challenge rather than hospitality in her tone. She said nothing more until she had sat down, poured milk into her coffee and stirred it.

Then she said no.

“No. I can’t do that. And the reason is, I’m not going to upset him.”

“Would it upset him?” Grant said earnestly.

“Yes, it would. It would. That’s no way to do. Bringing him home and taking him back. Bringing him home and taking him back, that’s just confusing him.”

“But wouldn’t he understand that it was just a visit? Wouldn’t he get into the pattern of it?”

“He understands everything all right.” She said this as if he had offered an insult to Aubrey. “But it’s still an interruption. And then I’ve got to get him all ready and get him into the car, and he’s a big man, he’s not so easy to manage as you might think. I’ve got to maneuver him into the car and pack his chair along and all that and what for? If I go to all that trouble I’d prefer to take him someplace that was more fun.”

“But even if I agreed to do it?” Grant said, keeping his tone hopeful and reasonable. “It’s true, you shouldn’t have the trouble.”

“You couldn’t,” she said flatly. “You don’t know him. You couldn’t handle him. He wouldn’t stand for you doing for him. All that bother and what would he get out of it?”

Grant didn’t think he should mention Fiona again.

“It’d make more sense to take him to the mall,” she said. “Where he could see kids and whatnot. If it didn’t make him sore about his own two grandsons he never gets to see. Or now the lake boats are starting to run again, he might get a charge out of going and watching that.”

She got up and fetched her cigarettes and lighter from the window above the sink.

“You smoke?” she said.

He said no thanks, though he didn’t know if a cigarette was being offered.

“Did you never? Or did you quit?”

“Quit,” he said.

“How long ago was that?”

He thought about it.

“Thirty years. No – more.”

He had decided to quit around the time he started up with Jacqui. But he couldn’t remember whether he quit first, and thought a big reward was coming to him for quitting, or thought that the time had come to quit, now that he had such a powerful diversion.

“I’ve quit quitting,” she said, lighting up. “Just made a resolution to quit quitting, that’s all.”

Maybe that was the reason for the wrinkles. Somebody – a woman – had told him that women who smoked developed a special set of fine facial wrinkles. But it could have been from the sun, or just the nature of her skin – her neck was noticeably wrinkled as well. Wrinkled neck, youthfully full and up-tilted breasts. Women of her age usually had these contradictions. The bad and good points, the genetic luck or lack of it, all mixed up together. Very few kept their beauty whole, though shadowy, as Fiona had done.

And perhaps that wasn’t even true. Perhaps he only thought that because he’d known Fiona when she was young. Perhaps to get that impression you had to have known a woman when she was young.

So when Aubrey looked at his wife did he see a high-school girl full of scorn and sass, with an intriguing tilt to her robin’s-egg blue eyes, pursing her fruity lips around a forbidden cigarette?

“So your wife’s depressed?” Aubrey’s wife said. “What’s your wife’s name? I forget.”

“It’s Fiona.”

“Fiona. And what’s yours? I don’t think I ever was told that.”

Grant said, “It’s Grant.”

She stuck her hand out unexpectedly across the table.

“Hello, Grant. I’m Marian.”

“So now we know each other’s name,” she said, “there’s no point in not telling you straight out what I think. I don’t know if he’s still so stuck on seeing your – on seeing Fiona. Or not. I don’t ask him and he’s not telling me. Maybe just a passing fancy. But I don’t feel like taking him back there in case it turns out to be more than that. I can’t afford to risk it. I don’t want him getting hard to handle. I don’t want him upset and carrying on. I’ve got my hands full with him as it is. I don’t have any help. It’s just me here. I’m it.”

“Did you ever consider – it is very hard for you—” Grant said – “did you ever consider his going in there for good?”

He had lowered his voice almost to a whisper, but she did not seem to feel a need to lower hers.

“No,” she said. “I’m keeping him right here.”

Grant said, “Well. That’s very good and noble of you.”

He hoped the word “noble” had not sounded sarcastic. He had not meant it to be.

“You think so?” she said. “Noble is not what I’m thinking about.”

“Still. It’s not easy.”

“No, it isn’t. But the way I am, I don’t have much choice. If I put him in there I don’t have the money to pay for him unless I sell the house. The house is what we own outright. Otherwise I don’t have anything in the way of resources. I get the pension next year, and I’ll have his pension and my pension, but even so I could not afford to keep him there and hang on to the house. And it means a lot to me, my house does.”

“It’s very nice,” said Grant.

“Well, it’s all right. I put a lot into it. Fixing it up and keeping it up.”

“I’m sure you did. You do.”

“I don’t want to lose it.”

“No.”

“I’m not going to lose it.”

“I see your point.”

“The company left us high and dry,” she said. “I don’t know all the ins and outs of it, but basically he got shoved out. It ended up with them saying he owed them money and when I tried to find out what was what he just went on saying it’s none of my business. What I think is he did something pretty stupid. But I’m not supposed to ask, so I shut up. You’ve been married. You are married. You know how it is. And in the middle of me finding out about this we’re supposed to go on this trip with these people and can’t get out of it. And on the trip he takes sick from this virus you never heard of and goes into a coma. So that pretty well gets him off the hook.”

Grant said, “Bad luck.”

“I don’t mean exactly that he got sick on purpose. It just happened. He’s not mad at me anymore and I’m not mad at him. It’s just life.”

“That’s true.”

“You can’t beat life.”

She flicked her tongue in a cat’s businesslike way across her top lip, getting the cookie crumbs. “I sound like I’m quite the philosopher, don’t I? They told me out there you used to be a university professor.”

“Quite a while ago,” Grant said.

“I’m not much of an intellectual,” she said.

“I don’t know how much I am, either.”

“But I know when my mind’s made up. And it’s made up. I’m not going to let go of the house. Which means I’m keeping him here and I don’t want him getting it in his head he wants to move anyplace else. It was probably a mistake putting him in there so I could get away, but I wasn’t going to get another chance, so I took it. So. Now I know better.”

She shook out another cigarette.

“I bet I know what you’re thinking,” she said. “You’re thinking there’s a mercenary type of a person.”

“I’m not making judgments of that sort. It’s your life.”

“You bet it is.”

He thought they should end on a more neutral note. So he asked her if her husband had worked in a hardware store in the summers, when he was going to school.

“I never heard about it,” she said. “I wasn’t raised here.”

DRIVING HOME, he noticed that the swamp hollow that had been filled with snow and the formal shadows of tree trunks was now lighted up with skunk lilies. Their fresh, edible-looking leaves were the size of platters. The flowers sprang straight up like candle flames, and there were so many of them, so pure a yellow, that they set a light shooting up from the earth on this cloudy day. Fiona had told him that they generated a heat of their own as well. Rummaging around in one of her concealed pockets of information, she said that you were supposed to be able to put your hand inside the curled petal and feel the heat. She said that she had tried it, but she couldn’t be sure if what she felt was heat or her imagination. The heat attracted bugs.

“Nature doesn’t fool around just being decorative.”

He had failed with Aubrey’s wife. Marian. He had foreseen that he might fail, but he had not in the least foreseen why. He had thought that all he’d have to contend with would be a woman’s natural sexual jealousy – or her resentment, the stubborn remains of sexual jealousy.

He had not had any idea of the way she might be looking at things. And yet in some depressing way the conversation had not been unfamiliar to him. That was because it reminded him of conversations he’d had with people in his own family. His uncles, his relatives, probably even his mother, had thought the way Marian thought. They had believed that when other people did not think that way it was because they were kidding themselves – they had got too airy-fairy, or stupid, on account of their easy and protected lives or their education. They had lost touch with reality. Educated people, literary people, some rich people like Grant’s socialist in-laws had lost touch with reality. Due to an unmerited good fortune or an innate silliness. In Grant’s case, he suspected, they pretty well believed it was both.

That was how Marian would see him, certainly. A silly person, full of boring knowledge and protected by some fluke from the truth about life. A person who didn’t have to worry about holding on to his house and could go around thinking his complicated thoughts. Free to dream up the fine, generous schemes that he believed would make another person happy.

What a jerk, she would be thinking now.

Being up against a person like that made him feel hopeless, exasperated, finally almost desolate. Why? Because he couldn’t be sure of holding on to himself against that person? Because he was afraid that in the end they’d be right? Fiona wouldn’t feel any of that misgiving. Nobody had beat her down, narrowed her in, when she was young. She’d been amused by his upbringing, able to think its harsh notions quaint.

Just the same, they have their points, those people. (He could hear himself now arguing with somebody. Fiona?) There’s some advantage to the narrow focus. Marian would probably be good in a crisis. Good at survival, able to scrounge for food and able to take the shoes off a dead body in the street.

Trying to figure out Fiona had always been frustrating. It could be like following a mirage. No – like living in a mirage. Getting close to Marian would present a different problem. It would be like biting into a litchi nut. The flesh with its oddly artificial allure, its chemical taste and perfume, shallow over the extensive seed, the stone.

HE MIGHT HAVE married her. Think of it. He might have married some girl like that. If he’d stayed back where he belonged. She’d have been appetizing enough, with her choice breasts. Probably a flirt. The fussy way she had of shifting her buttocks on the kitchen chair, her pursed mouth, a slightly contrived air of menace – that was what was left of the more or less innocent vulgarity of a small-town flirt.

She must have had some hopes, when she picked Aubrey. His good looks, his salesman’s job, his white-collar expectations. She must have believed that she would end up better off than she was now. And so it often happened with those practical people. In spite of their calculations, their survival instincts, they might not get as far as they had quite reasonably expected. No doubt it seemed unfair.

In the kitchen the first thing he saw was the light blinking on his answering machine. He thought the same thing he always thought now. Fiona.

He pressed the button before he got his coat off.

“Hello, Grant. I hope I got the right person. I just thought of something. There is a dance here in town at the Legion supposed to be for singles on Saturday night, and I am on the supper committee, which means I can bring a free guest. So I wondered whether you would happen to be interested in that? Call me back when you get a chance.”

A woman’s voice gave a local number. Then there was a beep, and the same voice started talking again.

“I just realized I’d forgot to say who it was. Well you probably recognized the voice. It’s Marian. I’m still not so used to these machines. And I wanted to say I realize you’re not a single and I don’t mean it that way. I’m not either, but it doesn’t hurt to get out once in a while. Anyway, now I’ve said all this I really hope it’s you I’m talking to. It did sound like your voice. If you are interested you can call me and if you are not you don’t need to bother. I just thought you might like the chance to get out. It’s Marian speaking. I guess I already said that. Okay, then. Good-bye.”

Her voice on the machine was different from the voice he’d heard a short time ago in her house. Just a little different in the first message, more so in the second. A tremor of nerves there, an affected nonchalance, a hurry to get through and a reluctance to let go.

Something had happened to her. But when had it happened? If it had been immediate, she had concealed it very successfully all the time he was with her. More likely it came on her gradually, maybe after he’d gone away. Not necessarily as a blow of attraction. Just the realization that he was a possibility, a man on his own. More or less on his own. A possibility that she might as well try to follow up.

But she’d had the jitters when she made the first move. She had put herself at risk. How much of herself, he could not yet tell. Generally a woman’s vulnerability increased as time went on, as things progressed. All you could tell at the start was that if there was an edge of it now, there’d be more later.

It gave him a satisfaction – why deny it? – to have brought that out in her. To have roused something like a shimmer, a blurring, on the surface of her personality. To have heard in her testy, broad vowels this faint plea.

He set out the eggs and mushrooms to make himself an omelette. Then he thought he might as well pour a drink.

Anything was possible. Was that true – was anything possible? For instance, if he wanted to, would he be able to break her down, get her to the point where she might listen to him about taking Aubrey back to Fiona? And not just for visits, but for the rest of Aubrey’s life. Where could that tremor lead them? To an upset, to the end of her self-preservation? To Fiona’s happiness?

It would be a challenge. A challenge and a creditable feat. Also a joke that could never be confided to anybody – to think that by his bad behavior he’d be doing good for Fiona.

But he was not really capable of thinking about it. If he did think about it, he’d have to figure out what would become of him and Marian, after he’d delivered Aubrey to Fiona. It would not work – unless he could get more satisfaction than he foresaw, finding the stone of blameless self-interest inside her robust pulp.

You never quite knew how such things would turn out. You almost knew, but you could never be sure.

She would be sitting in her house now, waiting for him to call. Or probably not sitting. Doing things to keep herself busy. She seemed to be a woman who would keep busy. Her house had certainly shown the benefits of nonstop attention. And there was Aubrey – care of him had to continue as usual. She might have given him an early supper – fitting his meals to a Meadowlake timetable in order to get him settled for the night earlier and free herself of his routine for the day. (What would she do about him when she went to the dance? Could he be left alone or would she get a sitter? Would she tell him where she was going, introduce her escort? Would her escort pay the sitter?)

She might have fed Aubrey while Grant was buying the mushrooms and driving home. She might now be preparing him for bed. But all the time she would be conscious of the phone, of the silence of the phone.Maybe she would have calculated how long it would take Grant to drive home. His address in the phone book would have given her a rough idea of where he lived. She would calculate how long, then add to that time for possible shopping for supper (figuring that a man alone would shop every day). Then a certain amount of time for him to get around to listening to his messages. And as the silence persisted she would think of other things. Other errands he might have had to do before he got home. Or perhaps a dinner out, a meeting that meant he would not get home at suppertime at all.

She would stay up late, cleaning her kitchen cupboards, watching television, arguing with herself about whether there was still a chance.

What conceit on his part. She was above all things a sensible woman. She would go to bed at her regular time thinking that he didn’t look as if he’d be a decent dancer anyway. Too stiff, too professorial.

He stayed near the phone, looking at magazines, but he didn’t pick it up when it rang again.

“Grant. This is Marian. I was down in the basement putting the wash in the dryer and I heard the phone and when I got upstairs whoever it was had hung up. So I just thought I ought to say I was here. If it was you and if you are even home. Because I don’t have a machine obviously, so you couldn’t leave a message. So I just wanted. To let you know.

“Bye.”

The time was now twenty-five after ten.

Bye.

He would say that he’d just got home. There was no point in bringing to her mind the picture of his sitting here, weighing the pros and cons.

Drapes. That would be her word for the blue curtains – drapes. And why not? He thought of the ginger cookies so perfectly round that she’d had to announce they were homemade, the ceramic coffee mugs on their ceramic tree. A plastic runner, he was sure, protecting the hall carpet. A high-gloss exactness and practicality that his mother had never achieved but would have admired – was that why he could feel this twinge of bizarre and unreliable affection? Or was it because he’d had two more drinks after the first?

The walnut-stain tan – he believed now that it was a tan – of her face and neck would most likely continue into her cleavage, which would be deep, crepey-skinned, odorous and hot. He had that to think of, as he dialled the number that he had already written down. That and the practical sensuality of her cat’s tongue. Her gemstone eyes.

FIONA WAS IN her room but not in bed. She was sitting by the open window, wearing a seasonable but oddly short and bright dress. Through the window came a heady, warm blast of lilacs in bloom and the spring manure spread over the fields.

She had a book open in her lap.

She said, “Look at this beautiful book I found, it’s about Iceland. You wouldn’t think they’d leave valuable books lying around in the rooms. The people staying here are not necessarily honest. And I think they’ve got the clothes mixed up. I never wear yellow.”

“Fiona…,” he said.

“You’ve been gone a long time. Are we all checked out now?”

“Fiona, I’ve brought a surprise for you. Do you remember Aubrey?”

She stared at him for a moment, as if waves of wind had come beating into her face. Into her face, into her head, pulling everything to rags.

“Names elude me,” she said harshly.

Then the look passed away as she retrieved, with an effort, some bantering grace. She set the book down carefully and stood up and lifted her arms to put them around him. Her skin or her breath gave off a faint new smell, a smell that seemed to him like that of the stems of cut flowers left too long in their water.

“I’m happy to see you,” she said, and pulled his earlobes.

“You could have just driven away,” she said. “Just driven away without a care in the world and forsook me. Forsooken me. Forsaken.”

He kept his face against her white hair, her pink scalp, her sweetly shaped skull. He said, Not a chance.