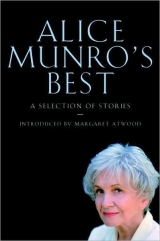

Текст книги "Alice Munro's Best"

Автор книги: Alice Munro

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Rose hears her father come in. She stiffens, a tremor runs through her legs, she feels them shiver on the oilcloth. Called away from some peaceful, absorbing task, away from the words running in his head, called out of himself, her father has to say something. He says, “Well? What’s wrong?”

Now comes another voice of Flo’s. Enriched, hurt, apologetic, it seems to have been manufactured on the spot. She is sorry to have called him from his work. Would never have done it if Rose was not driving her to distraction. How to distraction? With her back talk and impudence and her terrible tongue. The things Rose has said to Flo are such that if Flo had said them to her mother, she knows her father would have thrashed her into the ground.

Rose tries to butt in, to say this isn’t true.

What isn’t true?

Her father raises a hand, doesn’t look at her, says, “Be quiet.”

When she says it isn’t true, Rose means that she herself didn’t start this, only responded, that she was goaded by Flo, who is now, she believes, telling the grossest sort of lies, twisting everything to suit herself. Rose puts aside her other knowledge that whatever Flo has said or done, whatever she herself has said or done, does not really matter at all. It is the struggle itself that counts, and that can’t be stopped, can never be stopped, short of where it has got to now.

Flo’s knees are dirty, in spite of the pad. The scrub rag is still hanging over Rose’s foot.

Her father wipes his hands, listening to Flo. He takes his time. He is slow at getting into the spirit of things, tired in advance, maybe, on the verge of rejecting the role he has to play. He won’t look at Rose, but at any sound or stirring from Rose, he holds up his hand.

“Well, we don’t need the public in on this, that’s for sure,” Flo says, and she goes to lock the door of the store, putting in the store window the sign that says BACK SOON, a sign Rose made for her with a great deal of fancy curving and shading of letters in black and red crayon. When she comes back she shuts the door to the store, then the door to the stairs, then the door to the woodshed.

Her shoes have left marks on the clean wet part of the floor.

“Oh, I don’t know,” she says now, in a voice worn down from its emotional peak. “I don’t know what to do about her.” She looks down and sees her dirty knees (following Rose’s eyes) and rubs at them viciously with her bare hands, smearing the dirt around.

“She humiliates me,” she says, straightening up. There it is, the explanation. “She humiliates me,” she repeats with satisfaction. “She has no respect.”

“I do not!”

“Quiet, you!” says her father.

“If I hadn’t called your father you’d still be sitting there with that grin on your face! What other way is there to manage you?”

Rose detects in her father some objections to Flo’s rhetoric, some embarrassment and reluctance. She is wrong, and ought to know she is wrong, in thinking that she can count on this. The fact that she knows about it, and he knows she knows, will not make things any better. He is beginning to warm up. He gives her a look. This look is at first cold and challenging. It informs her of his judgment, of the hopelessness of her position. Then it clears, it begins to fill up with something else, the way a spring fills up when you clear the leaves away. It fills with hatred and pleasure. Rose sees that and knows it. Is that just a description of anger, should she see his eyes filling up with anger? No. Hatred is right. Pleasure is right. His face loosens and changes and grows younger, and he holds up his hand this time to silence Flo.

“All right,” he says, meaning that’s enough, more than enough, this part is over, things can proceed. He starts to loosen his belt.

Flo has stopped anyway. She has the same difficulty Rose does, a difficulty in believing that what you know must happen really will happen, that there comes a time when you can’t draw back.

“Oh, I don’t know, don’t be too hard on her.” She is moving around nervously as if she has thoughts of opening some escape route. “Oh, you don’t have to use the belt on her. Do you have to use the belt?”

He doesn’t answer. The belt is coming off, not hastily. It is being grasped at the necessary point. All right you. He is coming over to Rose. He pushes her off the table. His face, like his voice, is quite out of character. He is like a bad actor, who turns a part grotesque. As if he must savor and insist on just what is shameful and terrible about this. That is not to say he is pretending, that he is acting, and does not mean it. He is acting, and he means it. Rose knows that, she knows everything about him.

She has since wondered about murders, and murderers. Does the thing have to be carried through, in the end, partly for the effect, to prove to the audience of one – who won’t be able to report, only register, the lesson – that such a thing can happen, that there is nothing that can’t happen, that the most dreadful antic is justified, feelings can be found to match it?

She tries again looking at the kitchen floor, that clever and comforting geometrical arrangement, instead of looking at him or his belt. How can this go on in front of such daily witnesses – the linoleum, the calendar with the mill and creek and autumn trees, the old accommodating pots and pans?

Hold out your hand!

Those things aren’t going to help her, none of them can rescue her. They turn bland and useless, even unfriendly. Pots can show malice, the patterns of linoleum can leer up at you, treachery is the other side of dailiness.

At the first, or maybe the second, crack of pain, she draws back. She will not accept it. She runs around the room, she tries to get to the doors. Her father blocks her off. Not an ounce of courage or of stoicism in her, it would seem. She runs, she screams, she implores. Her father is after her, cracking the belt at her when he can, then abandoning it and using his hands. Bang over the ear, then bang over the other ear. Back and forth, her head ringing. Bang in the face. Up against the wall and bang in the face again. He shakes her and hits her against the wall, he kicks her legs. She is incoherent, insane, shrieking. Forgive me! Oh please, forgive me!

Flo is shrieking too. Stop, stop!

Not yet. He throws Rose down. Or perhaps she throws herself down. He kicks her legs again. She has given up on words but is letting out a noise, the sort of noise that makes Flo cry, Oh, what if people can hear her? The very last-ditch willing sound of humiliation and defeat it is, for it seems Rose must play her part in this with the same grossness, the same exaggeration, that her father displays, playing his. She plays his victim with a self-indulgence that arouses, and maybe hopes to arouse, his final, sickened contempt.

They will give this anything that is necessary, it seems, they will go to any lengths.

Not quite. He has never managed really to injure her, though there are times, of course, when she prays that he will. He hits her with an open hand, there is some restraint in his kicks.

Now he stops, he is out of breath. He allows Flo to move in, he grabs Rose up and gives her a push in Flo’s direction, making a sound of disgust. Flo retrieves her, opens the stair door, shoves her up the stairs.

“Go on up to your room now! Hurry!”

Rose goes up the stairs, stumbling, letting herself stumble, letting herself fall against the steps. She doesn’t bang her door because a gesture like that could still bring him after her, and anyway, she is weak. She lies on the bed. She can hear through the stovepipe hole Flo snuffling and remonstrating, her father saying angrily that Flo should have kept quiet then, if she did not want Rose punished she should not have recommended it. Flo says she never recommended a hiding like that.

They argue back and forth on this. Flo’s frightened voice is growing stronger, getting its confidence back. By stages, by arguing, they are being drawn back into themselves. Soon it’s only Flo talking; he will not talk anymore. Rose has had to fight down her noisy sobbing, so as to listen to them, and when she loses interest in listening, and wants to sob some more, she finds she can’t work herself up to it. She has passed into a state of calm, in which outrage is perceived as complete and final. In this state events and possibilities take on a lovely simplicity. Choices are mercifully clear. The words that come to mind are not the quibbling, seldom the conditional. “Never” is a word to which the right is suddenly established. She will never speak to them, she will never look at them with anything but loathing, she will never forgive them. She will punish them; she will finish them. Encased in these finalities, and in her bodily pain, she floats in curious comfort, beyond herself, beyond responsibility.

Suppose she dies now? Suppose she commits suicide? Suppose she runs away? Any of these things would be appropriate. It is only a matter of choosing, of figuring out the way. She floats in her pure superior state as if kindly drugged.

And just as there is a moment, when you are drugged, in which you feel perfectly safe, sure, unreachable, and then without warning and right next to it a moment in which you know the whole protection has fatally cracked, though it is still pretending to hold soundly together, so there is a moment now – the moment, in fact, when Rose hears Flo step on the stairs – that contains for her both present peace and freedom and a sure knowledge of the whole down-spiralling course of events from now on.

Flo comes into the room without knocking, but with a hesitation that shows it might have occurred to her. She brings a jar of cold cream. Rose is hanging on to advantage as long as she can, lying face down on the bed, refusing to acknowledge or answer.

“Oh, come on,” Flo says uneasily. “You aren’t so bad off, are you? You put some of this on and you’ll feel better.”

She is bluffing. She doesn’t know for sure what damage has been done. She has the lid off the cold cream. Rose can smell it. The intimate, baby ish, humiliating smell. She won’t allow it near her. But in order to avoid it, the big ready clot of it in Flo’s hand, she has to move. She scuffles, resists, loses dignity, and lets Flo see there is not really much the matter.

“All right,” Flo says. “You win. I’ll leave it here and you can put it on when you like.”

Later still a tray will appear. Flo will put it down without a word and go away. A large glass of chocolate milk on it, made with Vita-Malt from the store. Some rich streaks of Vita-Malt around the bottom of the glass. Little sandwiches, neat and appetizing. Canned salmon of the first quality and reddest color, plenty of mayonnaise. A couple of butter tarts from a bakery package, chocolate biscuits with a peppermint filling. Rose’s favorites, in the sandwich, tart, and cookie line. She will turn away, refuse to look, but left alone with these eatables will be miserably tempted; roused and troubled and drawn back from thoughts of suicide or flight by the smell of salmon, the anticipation of crisp chocolate, she will reach out a finger, just to run it around the edge of one of the sandwiches (crusts cut off!) to get the overflow, get a taste. Then she will decide to eat one, for strength to refuse the rest. One will not be noticed. Soon, in helpless corruption, she will eat them all. She will drink the chocolate milk, eat the tarts, eat the cookies. She will get the malty syrup out of the bottom of the glass with her finger, though she sniffles with shame. Too late.

Flo will come up and get the tray. She may say, “I see you got your appetite still,” or, “Did you like the chocolate milk, was it enough syrup in it?” depending on how chastened she is feeling, herself. At any rate, all advantage will be lost. Rose will understand that life has started up again, that they will all sit around the table eating again, listening to the radio news. Tomorrow morning, maybe even tonight. Unseemly and unlikely as that may be. They will be embarrassed, but rather less than you might expect considering how they have behaved. They will feel a queer lassitude, a convalescent indolence, not far off satisfaction.

One night after a scene like this they were all in the kitchen. It must have been summer, or at least warm weather, because her father spoke of the old men who sat on the bench in front of the store.

“Do you know what they’re talking about now?” he said, and nodded his head toward the store to show who he meant, though of course they were not there now, they went home at dark.

“Those old coots,” said Flo. “What?”

There was about them both a geniality not exactly false but a bit more emphatic than was normal, without company.

Rose’s father told them then that the old men had picked up the idea somewhere that what looked like a star in the western sky, the first star that came out after sunset, the evening star, was in reality an airship hovering over Bay City, Michigan, on the other side of Lake Huron. An American invention, sent up to rival the heavenly bodies. They were all in agreement about this, the idea was congenial to them. They believed it to be lit by ten thousand electric light bulbs. Her father had ruthlessly disagreed with them, pointing out that it was the planet Venus they saw, which had appeared in the sky long before the invention of an electric light bulb. They had never heard of the planet Venus.

“Ignoramuses,” said Flo. At which Rose knew, and knew her father knew, that Flo had never heard of the planet Venus either. To distract them from this, or even apologize for it, Flo put down her teacup, stretched out with her head resting on the chair she had been sitting on and her feet on another chair (somehow she managed to tuck her dress modestly between her legs at the same time), and lay stiff as a board, so that Brian cried out in delight, “Do that! Do that!”

Flo was double-jointed and very strong. In moments of celebration or emergency she would do tricks.

They were silent while she turned herself around, not using her arms at all but just her strong legs and feet. Then they all cried out in triumph, though they had seen it before.

Just as Flo turned herself Rose got a picture in her mind of that air ship, an elongated transparent bubble, with its strings of diamond lights, floating in the miraculous American sky.

“The planet Venus!” her father said, applauding Flo. “Ten thousand electric lights!”

There was a feeling of permission, relaxation, even a current of happiness, in the room.

YEARS LATER, many years later, on a Sunday morning, Rose turned on the radio. This was when she was living by herself in Toronto.

Well, sir.

It was a different kind of place in our day. Yes, it was.

It was all horses then. Horses and buggies. Buggy races up and down the main street on the Saturday nights.

“Just like the chariot races,” says the announcer’s, or interviewer’s, smooth encouraging voice.

I never seen a one of them.

“No, sir, that was the old Roman chariot races I was referring to. That was before your time.”

Musta been before my time. I’m a hunerd and two years old.

“That’s a wonderful age, sir.”

It is so.

She left it on, as she went around the apartment kitchen, making coffee for herself. It seemed to her that this must be a staged interview, a scene from some play, and she wanted to find out what it was. The old man’s voice was so vain and belligerent, the interviewer’s quite hopeless and alarmed, under its practiced gentleness and ease. You were surely meant to see him holding the microphone up to some toothless, reckless, preening centenarian, wondering what in God’s name he was doing here, and what would he say next?

“They must have been fairly dangerous.”

What was dangerous?

“Those buggy races.”

They was. Dangerous. Used to be the runaway horses. Used to be a-plenty of accidents. Fellows was dragged along on the gravel and cut their face open. Wouldna matter so much if they was dead. Heh.

Some of them horses was the high-steppers. Some, they had to have the mustard under their tail. Some wouldn step out for nothin. That’s the thing it is with the horses. Some’ll work and pull till they drop down dead and some wouldn pull your cock out of a pail of lard. Hehe.

It must be a real interview after all. Otherwise they wouldn’t have put that in, wouldn’t have risked it. It’s all right if the old man says it. Local color. Anything rendered harmless and delightful by his hundred years.

Accidents all the time then. In the mill. Foundry. Wasn’t the precautions.

“You didn’t have so many strikes then, I don’t suppose? You didn’t have so many unions?”

Everybody taking it easy nowadays. We worked and we was glad to get it. Worked and was glad to get it.

“You didn’t have television.”

Didn’t have no TV. Didn’t have no radio. No picture show.

“You made your own entertainment.”

That’s the way we did.

“You had a lot of experiences young men growing up today will never have.”

Experiences.

“Can you recall any of them for us?”

I eaten groundhog meat one time. One winter. You wouldna cared for it. Heh.

There was a pause, of appreciation, it would seem, then the announcer’s voice saying that the foregoing had been an interview with Mr. Wilfred Nettleton of Hanratty, Ontario, made on his hundred and second birthday, two weeks before his death, last spring. A living link with our past. Mr. Nettleton had been interviewed in the Wawanash County Home for the Aged.

Hat Nettleton.

Horsewhipper into centenarian. Photographed on his birthday, fussed over by nurses, kissed no doubt by a girl reporter. Flashbulbs popping at him. Tape recorder drinking in the sound of his voice. Oldest resident. Oldest horsewhipper. Living link with our past.

Looking out from her kitchen window at the cold lake, Rose was longing to tell somebody. It was Flo who would enjoy hearing. She thought of her saying Imagine! in a way that meant she was having her worst suspicions gorgeously confirmed. But Flo was in the same place Hat Nettleton had died in, and there wasn’t any way Rose could reach her. She had been there even when that interview was recorded, though she would not have heard it, would not have known about it. After Rose put her in the Home, a couple of years earlier, she had stopped talking. She had removed herself, and spent most of her time sitting in a corner of her crib, looking crafty and disagreeable, not answering anybody, though she occasionally showed her feelings by biting a nurse.

THE BEGGAR MAID

PATRICK BLATCHFORD was in love with Rose. This had become a fixed, even furious, idea with him. For her, a continual surprise. He wanted to marry her. He waited for her after classes, moved in and walked beside her, so that anybody she was talking to would have to reckon with his presence. He would not talk when these friends or classmates of hers were around, but he would try to catch her eye, so that he could indicate by a cold incredulous look what he thought of their conversation. Rose was flattered, but nervous. A girl named Nancy Falls, a friend of hers, mispronounced Metternich in front of him. He said to her later, “How can you be friends with people like that?”

Nancy and Rose had gone and sold their blood together, at Victoria Hospital. They each got fifteen dollars. They spent most of the money on evening shoes, tarty silver sandals. Then because they were sure the bloodletting had caused them to lose weight, they had hot fudge sundaes at Boomers. Why was Rose unable to defend Nancy to Patrick?

Patrick was twenty-four years old, a graduate student, planning to be a history professor. He was tall, thin, fair, and good-looking, though he had a long pale-red birthmark, dribbling like a tear down his temple and his cheek. He apologized for it, but said it was fading as he got older. When he was forty, it would have faded away. It was not the birthmark that cancelled out his good looks, Rose thought. (Something did cancel them out, or at least diminish them, for her; she had to keep reminding herself they were there.) There was something edgy, jumpy, disconcerting about him. His voice would break under stress – with her, it seemed he was always under stress – he knocked dishes and cups off tables, spilled drinks and bowls of peanuts, like a comedian. He was not a comedian; nothing could be further from his intentions. He came from British Columbia. His family was rich.

He arrived early to pick Rose up, when they were going to the movies. He wouldn’t knock, he knew he was early. He sat on the step outside Dr. Henshawe’s door. This was in the winter, it was dark out, but there was a little coach lamp beside the door.

“Oh, Rose! Come and look!” called Dr. Henshawe, in her soft, amused voice, and they looked down together from the dark window of the study. “The poor young man,” said Dr. Henshawe tenderly. Dr. Henshawe was in her seventies. She was a former English professor, fastidious and lively. She had a lame leg, but a still youthfully, charmingly tilted head, with white braids wound around it.

She called Patrick poor because he was in love, and perhaps also because he was a male, doomed to push and blunder. Even from up here he looked stubborn and pitiable, determined and dependent, sitting out there in the cold.

“Guarding the door,” Dr. Henshawe said. “Oh, Rose!”

Another time she said disturbingly, “Oh, dear, I’m afraid he is after the wrong girl.”

Rose didn’t like her saying that. She didn’t like her laughing at Patrick. She didn’t like Patrick sitting out on the steps that way, either. He was asking to be laughed at. He was the most vulnerable person Rose had ever known; he made himself so, didn’t know anything about protecting himself. But he was also full of cruel judgments, he was full of conceit.

“YOU ARE A SCHOLAR, Rose,” Dr. Henshawe would say. “This will interest you.” Then she would read aloud something from the paper, or, more likely, something from Canadian Forum or the Atlantic Monthly. Dr. Henshawe had at one time headed the city’s school board, she was a founding member of Canada’s Socialist Party. She still sat on committees, wrote letters to the paper, reviewed books. Her father and mother had been medical missionaries; she had been born in China. Her house was small and perfect. Polished floors, glowing rugs, Chinese vases, bowls, and landscapes, black carved screens. Much that Rose could not appreciate, at the time.

She could not really distinguish between the little jade animals on Dr. Henshawe’s mantelpiece and the ornaments displayed in the jewelry-store window in Hanratty, though she could now distinguish between either of these and the things Flo bought from the five-and-ten. She could not really decide how much she liked being at Dr. Henshawe’s. At times she felt discouraged, sitting in the dining room with a linen napkin on her knee, eating from fine white plates on blue placemats. For one thing, there was never enough to eat, and she had taken to buying doughnuts and chocolate bars and hiding them in her room. The canary swung on its perch in the dining-room window and Dr. Henshawe directed conversation. She talked about politics, about writers. She mentioned Frank Scott and Dorothy Livesay. She said Rose must read them. Rose must read this, she must read that. Rose became sullenly determined not to. She was reading Thomas Mann. She was reading Tolstoy.

Before she came to Dr. Henshawe’s, Rose had never heard of the working class. She took the designation home.

“This would have to be the last part of town where they put the sewers,” Flo said.

“Of course,” Rose said coolly. “This is the working-class part of town.”

“Working class?” said Flo. “Not if the ones around here can help it.”

Dr. Henshawe’s house had done one thing. It had destroyed the naturalness, the taken-for-granted background, of home. To go back there was to go quite literally into a crude light. Flo had put fluorescent lights in the store and the kitchen. There was also, in a corner of the kitchen, a floor lamp Flo had won at Bingo; its shade was permanently wrapped in wide strips of cellophane. What Dr. Henshawe’s house and Flo’s house did best, in Rose’s opinion, was discredit each other. In Dr. Henshawe’s charming rooms there was always for Rose the raw knowledge of home, an indigestible lump, and at home now her sense of order and modulation elsewhere exposed such embarrassing sad poverty in people who never thought themselves poor. Poverty was not just wretchedness, as Dr. Henshawe seemed to think, it was not just deprivation. It meant having those ugly tube lights and being proud of them. It meant continual talk of money and malicious talk about new things people had bought and whether they were paid for. It meant pride and jealousy flaring over something like the new pair of plastic curtains, imitating lace, that Flo had bought for the front window. That as well as hanging your clothes on nails behind the door and being able to hear every sound from the bathroom. It meant decorating your walls with a number of admonitions, pious and cheerful and mildly bawdy.

THE LORD IS MY SHEPHERD

BELIEVE IN THE LORD JESUS CHRIST AND THOU SHALL

BE SAVED

Why did Flo have those, when she wasn’t even religious? They were what people had, common as calendars.

THIS IS MY KITCHEN AND I WILL DO AS I DARNED PLEASE

MORE THAN TWO PERSONS TO A BED IS DANGEROUS

AND UNLAWFUL

Billy Pope had brought that one. What would Patrick have to say about them? What would someone who was offended by a mispronunciation of Metternich think of Billy Pope’s stories?

Billy Pope worked in Tyde’s Butcher Shop. What he talked about most frequently now was the D.P., the Belgian, who had come to work there, and got on Billy Pope’s nerves with his impudent singing of French songs and his naive notions of getting on in this country, buying a butcher shop of his own.

“Don’t you think you can come over here and get yourself ideas,” Billy Pope said to the D.P. “It’s youse workin’ for us, and don’t think that’ll change into us workin’ for youse.” That shut him up, Billy Pope said.

Patrick would say from time to time that since her home was only fifty miles away he ought to come up and meet Rose’s family.

“There’s only my stepmother.”

“It’s too bad I couldn’t have met your father.”

Rashly, she had presented her father to Patrick as a reader of history, an amateur scholar. That was not exactly a lie, but it did not give a truthful picture of the circumstances.

“Is your stepmother your guardian?”

Rose had to say she did not know.

“Well, your father must have appointed a guardian for you in his will. Who administers his estate?”

His estate. Rose thought an estate was land, such as people owned in England.

Patrick thought it was rather charming of her to think that.

“No, his money and stocks and so on. What he left.”

“I don’t think he left any.”

“Don’t be silly,” Patrick said.

AND SOMETIMES Dr. Henshawe would say, “Well, you are a scholar, you are not interested in that.” Usually she was speaking of some event at the college: a pep rally, a football game, a dance. And usually she was right; Rose was not interested. But she was not eager to admit it. She did not seek or relish that definition of herself.

On the stairway wall hung graduation photographs of all the other girls, scholarship girls, who had lived with Dr. Henshawe. Most of them had got to be teachers, then mothers. One was a dietician, two were librarians, one was a professor of English, like Dr. Henshawe herself. Rose did not care for the look of them, for their soft-focused meekly smiling gratitude, their large teeth and maidenly rolls of hair. They seemed to be urging on her some deadly secular piety. There were no actresses among them, no brassy magazine journalists; none of them had latched on to the sort of life Rose wanted for herself. She wanted to perform in public. She thought she wanted to be an actress but she never tried to act, was afraid to go near the college drama productions. She knew she couldn’t sing or dance. She would really have liked to play the harp, but she had no ear for music. She wanted to be known and envied, slim and clever. She told Dr. Henshawe that if she had been a man she would have wanted to be a foreign correspondent.

“Then you must be one!” cried Dr. Henshawe alarmingly. “The future will be wide open for women. You must concentrate on languages. You must take courses in political science. And economics. Perhaps you could get a job on the paper for the summer. I have friends there.”

Rose was frightened at the idea of working on a paper, and she hated the introductory economics course; she was looking for a way of dropping it. It was dangerous to mention things to Dr. Henshawe.

SHE HAD GOT to live with Dr. Henshawe by accident. Another girl had been picked to move in but she got sick; she had t.b., and went instead to a sanatorium. Dr. Henshawe came up to the college office on the second day of registration to get the names of some other scholarship freshmen.

Rose had been in the office just a little while before, asking where the meeting of the scholarship students was to be held. She had lost her notice. The Bursar was giving a talk to the new scholarship students, telling them of ways to earn money and live cheaply and explaining the high standards of performance to be expected of them here if they wanted their payments to keep coming.

Rose found out the number of the room, and started up the stairs to the first floor. A girl came up beside her and said, “Are you on your way to three-oh-twelve, too?”

They walked together, telling each other the details of their scholarships. Rose did not yet have a place to live, she was staying at the Y. She did not really have enough money to be here at all. She had a scholarship for her tuition and the county prize to buy her books and a bursary of three hundred dollars to live on; that was all.

“You’ll have to get a job,” the other girl said. She had a larger bursary, because she was in science (that’s where the money is, the money’s all in science, she said seriously), but she was hoping to get a job in the cafeteria. She had a room in somebody’s basement. How much does your room cost? How much does a hot plate cost? Rose asked her, her head swimming with anxious calculations.