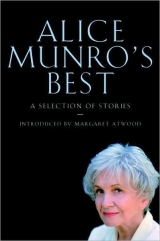

Текст книги "Alice Munro's Best"

Автор книги: Alice Munro

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Ian had phoned, she said. Ian had phoned and said he was flying into Toronto tomorrow. Work on his book had progressed more quickly than he had expected; he had changed his plans. Instead of waiting for the three weeks to be up, he was coming tomorrow to collect Sophie and the children and take them on a little trip. He wanted to go to Quebec City. He had never been there, and he thought the children should see the part of Canada where people spoke French.

“He got lonesome,” Philip said.

Sophie laughed. She said, “Yes. He got lonesome for us.”

Twelve days, Eve thought. Twelve days had passed of the three weeks. She had had to take the house for a month. She was letting her friend Dev use the apartment. He was another out-of-work actor, and was in such real or imagined financial peril that he answered the phone in various stage voices. She was fond of Dev, but she couldn’t go back and share the apartment with him.

Sophie said that they would drive to Quebec in the rented car, then drive straight back to the Toronto airport, where the car was to be turned in. No mention of Eve’s going along. There wasn’t room in the rented car. But couldn’t she have taken her own car? Philip riding with her, perhaps, for company. Or Sophie. Ian could take the children, if he was so lonesome for them, and give Sophie a rest. Eve and Sophie could ride together as they used to in the summer, travelling to some town they had never seen before, where Eve had got a job.

That was ridiculous. Eve’s car was nine years old and in no condition to make a long trip. And it was Sophie Ian had got lonesome for – you could tell that by her warm averted face. Also, Eve hadn’t been asked.

“Well that’s wonderful,” said Eve. “That he’s got along so well with his book.”

“It is,” said Sophie. She always had an air of careful detachment when she spoke of Ian’s book, and when Eve had asked what it was about she had said merely, “Urban geography.” Perhaps this was the correct behavior for academic wives – Eve had never known any.

“Anyway you’ll get some time by yourself,” Sophie said. “After all this circus. You’ll find out if you really would like to have a place in the country. A retreat.”

Eve had to start talking about something else, anything else, so that she wouldn’t bleat out a question about whether Sophie still thought of coming next summer.

“I had a friend who went on one of those real retreats,” she said. “He’s a Buddhist. No, maybe a Hindu. Not a real Indian.” (At this mention of Indians Sophie smiled in a way that said this was another subject that need not be gone into.) “Anyway, you could not speak on this retreat for three months. There were other people around all the time, but you could not speak to them. And he said that one of the things that often happened and that they were warned about was that you fell in love with one of these people you’d never spoken to. You felt you were communicating in a special way with them when you couldn’t talk. Of course it was a kind of spiritual love, and you couldn’t do anything about it. They were strict about that kind of thing. Or so he said.”

Sophie said, “So? When you were finally allowed to speak what happened?”

“It was a big letdown. Usually the person you thought you’d been communicating with hadn’t been communicating with you at all. Maybe they thought they’d been communicating that way with somebody else, and they thought—”

Sophie laughed with relief. She said, “So it goes.” Glad that there was to be no show of disappointment, no hurt feelings.

Maybe they had a tiff, thought Eve. This whole visit might have been tactical. Sophie might have taken the children off to show him something. Spent time with her mother, just to show him something. Planning future holidays without him, to prove to herself that she could do it. A diversion.

And the burning question was, Who did the phoning?

“Why don’t you leave the children here?” she said. “Just while you drive to the airport? Then just drive back and pick them up and take off. You’d have a little time to yourself and a little time alone with Ian. It’ll be hell with them in the airport.”

Sophie said, “I’m tempted.”

So in the end that was what she did.

Now Eve had to wonder if she herself had engineered that little change just so she could get to talk to Philip.

(Wasn’t it a big surprise when your dad phoned from California?

He didn’t phone. My mom phoned him.

Did she? Oh I didn’t know. What did she say?

She said, “I can’t stand it here, I’m sick of it, let’s figure out some plan to get me away.”)

EVE DROPPED HER voice to a matter-of-fact level, to indicate an interruption of the game. She said, “Philip. Philip, listen. I think we’ve got to stop this. That truck just belongs to some farmer and it’s going to turn in someplace and we can’t go on following.”

“Yes we can,” Philip said.

“No we can’t. They’d want to know what we were doing. They might be very mad.”

“We’ll call up our helicopters to come and shoot them.”

“Don’t be silly. You know this is just a game.”

“They’ll shoot them.”

“I don’t think they have any weapons,” said Eve, trying another tack. “They haven’t developed any weapons to destroy aliens.”

Philip said, “You’re wrong,” and began a description of some kind of rockets, which she did not listen to.

WHEN SHE WAS a child staying in the village with her brother and her parents, Eve had sometimes gone for drives in the country with her mother. They didn’t have a car – it was wartime, they had come here on the train. The woman who ran the hotel was friends with Eve’s mother, and they would be invited along when she drove to the country to buy corn or raspberries or tomatoes. Sometimes they would stop to have tea and look at the old dishes and bits of furniture for sale in some enterprising farm woman’s front parlor. Eve’s father preferred to stay behind and play checkers with some other men on the beach. There was a big cement square with a checkerboard painted on it, a roof protecting it but no walls, and there, even in the rain, the men moved oversized checkers around in a deliberate way, with long poles. Eve’s brother watched them or went swimming unsupervised – he was older. That was all gone now – the cement, even, was gone, or something had been built right on top of it. The hotel with its verandas extending over the sand was gone, and the railway station with its flower beds spelling out the name of the village. The railway tracks too. Instead there was a fake-old-fashioned mall with the satisfactory new supermarket and wineshop and boutiques for leisure wear and country crafts.

When she was quite small and wore a great hair bow on top of her head, Eve was fond of these country expeditions. She ate tiny jam tarts and cakes whose frosting was stiff on top and soft underneath, topped with a bleeding maraschino cherry. She was not allowed to touch the dishes or the lace-and-satin pincushions or the sallow-looking old dolls, and the women’s conversations passed over her head with a temporary and mildly depressing effect, like the inevitable clouds. But she enjoyed riding in the backseat imagining herself on horseback or in a royal coach. Later on she refused to go. She began to hate trailing along with her mother and being identified as her mother’s daughter. My daughter, Eve. How richly condescending, how mistakenly possessive, that voice sounded in her ears. (She was to use it, or some version of it, for years as a staple in some of her broadest, least accomplished acting.) She detested also her mother’s habit of dressing up, wearing large hats and gloves in the country, and sheer dresses on which there were raised flowers, like warts. The oxford shoes, on the other hand – they were worn to favor her mother’s corns – appeared embarrassingly stout and shabby.

“What did you hate most about your mother?” was a game that Eve would play with her friends in her first years free of home.

“Corsets,” one girl would say, and another would say, “Wet aprons.”

Hair nets. Fat arms. Bible quotations. “Danny Boy.”

Eve always said. “Her corns.”

She had forgotten all about this game until recently. The thought of it now was like touching a bad tooth.

Ahead of them the truck slowed and without signalling turned into a long tree-lined lane. Eve said, “I can’t follow them any farther, Philip,” and drove on. But as she passed the lane she noticed the gateposts. They were unusual, being shaped something like crude minarets and decorated with whitewashed pebbles and bits of colored glass. Neither one of them was straight, and they were half hidden by goldenrod and wild carrot, so that they had lost all reality as gateposts and looked instead like lost stage props from some gaudy operetta. The minute she saw them Eve remembered something else – a whitewashed outdoor wall in which there were pictures set. The pictures were stiff, fantastic, childish scenes. Churches with spires, castles with towers, square houses with square, lopsided, yellow windows. Triangular Christmas trees and tropical-colored birds half as big as the trees, a fat horse with dinky legs and burning red eyes, curly blue rivers, like lengths of ribbon, a moon and drunken stars and fat sunflowers nodding over the roofs of houses. All of this made of pieces of colored glass set into cement or plaster. She had seen it, and it wasn’t in any public place. It was out in the country, and she had been with her mother. The shape of her mother loomed in front of the wall – she was talking to an old farmer. He might only have been her mother’s age, of course, and looked old to Eve.

Her mother and the hotel woman did go to look at odd things on those trips; they didn’t just look at antiques. They had gone to see a shrub cut to resemble a bear, and an orchard of dwarf apple trees.

Eve didn’t remember the gateposts at all, but it seemed to her that they could not have belonged to any other place. She backed the car and swung around into the narrow track beneath the trees. The trees were heavy old Scotch pines, probably dangerous – you could see dangling half-dead branches, and branches that had already blown down or fallen down were lying in the grass and weeds on either side of the track. The car rocked back and forth in the ruts, and it seemed that Daisy approved of this motion. She began to make an accompanying noise. Whoppy. Whoppy. Whoppy.

This was something Daisy might remember – all she might remember – of this day. The arched trees, the sudden shadow, the interesting motion of the car. Maybe the white faces of the wild carrot that brushed at the windows. The sense of Philip beside her – his incomprehensible serious excitement, the tingling of his childish voice brought under unnatural control. A much vaguer sense of Eve – bare, freckly, sun-wrinkled arms, gray-blond frizzy curls held back by a black hairband. Maybe a smell. Not of cigarettes anymore, or of the touted creams and cosmetics on which Eve once spent so much of her money. Old skin? Garlic? Wine? Mouthwash? Eve might be dead when Daisy remembered this. Daisy and Philip might be estranged. Eve had not spoken to her own brother for three years. Not since he said to her on the phone, “You shouldn’t have become an actress if you weren’t equipped to make a better go of it.”

There wasn’t any sign of a house ahead, but through a gap in the trees the skeleton of a barn rose up, walls gone, beams intact, roof whole but flopping to one side like a funny hat. There seemed to be pieces of machinery, old cars or trucks, scattered around it, in the sea of flowering weeds. Eve had not much leisure to look – she was busy controlling the car on this rough track. The green truck had disappeared ahead of her – how far could it have gone? Then she saw that the lane curved. It curved; they left the shade of the pines and were out in the sunlight. The same sea foam of wild carrot, the same impression of rusting junk strewed about. A high wild hedge to one side, and there was the house, finally, behind it. A big house, two stories of yellowish-gray brick, an attic story of wood, its dormer windows stuffed with dirty foam rubber. One of the lower windows shone with aluminum foil covering it on the inside.

She had come to the wrong place. She had no memory of this house. There was no wall here around mown grass. Saplings grew up at random in the weeds.

The truck was parked ahead of her. And ahead of that she could see a patch of cleared ground where gravel had been spread and where she could have turned the car around. But she couldn’t get past the truck to do that. She had to stop, too. She wondered if the man in the truck had stopped where he did on purpose, so that she would have to explain herself. He was now getting out of the truck in a leisurely way. Without looking at her, he released the dog, which had been running back and forth and barking with a great deal of angry spirit. Once on the ground, it continued to bark, but didn’t leave the man’s side. The man wore a cap that shaded his face, so that Eve could not see his expression. He stood by the truck looking at them, not yet deciding to come any closer.

Eve unbuckled her seat belt.

“Don’t get out,” said Philip. “Stay in the car. Turn around. Drive away.”

“I can’t,” said Eve. “It’s all right. That dog’s just a yapper, he won’t hurt me.”

“Don’t get out.”

She should never have let that game get so far Out of control. A child of Philip’s age could get too carried away. “This isn’t part of the game,” she said. “He’s just a man.”

“I know,” said Philip. “But don’t get out.”

“Stop that,” said Eve, and got out and shut the door.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m sorry. I made a mistake. I thought this was somewhere else.”

The man said something like “Hey.”

“I was actually looking for another place,” said Eve. “It was a place where I came once when I was a little girl. There was a wall with pictures on it all made with pieces of broken glass. I think a cement wall, whitewashed. When I saw those pillars by the road, I thought this must be it. You must have thought we were following you. It sounds so silly.”

She heard the car door open. Philip got out, dragging Daisy behind him. Eve thought he had come to be close to her, and she put out her arm to welcome him. But he detached himself from Daisy and circled round Eve and spoke to the man. He had brought himself out of the alarm of a moment before and now he seemed steadier than Eve was.

“Is your dog friendly?” he said in a challenging way.

“She won’t hurt you,” the man said. “Long as I’m here, she’s okay. She gets in a tear because she’s not no more than a pup. She’s still not no more than a pup.”

He was a small man, no taller than Eve. He was wearing jeans and one of those open vests of colorful weave, made in Peru or Guatemala. Gold chains and medallions sparkled on his hairless, tanned, and muscular chest. When he spoke he threw his head back and Eve could see that his face was older than his body. Some front teeth were missing.

“We won’t bother you anymore,” she said. “Philip, I was just telling this man we drove down this road looking for a place I came when I was a little girl, and there were pictures made of colored glass set in a wall. But I made a mistake, this isn’t the place.”

“What’s its name?” said Philip.

“Trixie,” the man said, and on hearing her name the dog jumped up and bumped his arm. He swatted her down. “I don’t know about no pictures. I don’t live here. Harold, he’s the one would know.”

“It’s all right,” said Eve, and hoisted Daisy up on her hip. “If you could just move the truck ahead, then I could turn around.”

“I don’t know no pictures. See, if they was in the front part the house I never would’ve saw them because Harold, he’s got the front part of the house shut off.”

“No, they were outside,” said Eve. “It doesn’t matter. This was years and years ago.”

“Yeah. Yeah. Yeah,” the man was saying, warming to the conversation. “You come in and get Harold to tell you about it. You know Harold? He’s who owns it here. Mary, she owns it, but Harold he put her in the Home, so now he does. It wasn’t his fault, she had to go there.” He reached into the truck and took out two cases of beer. “I just had to go to town, Harold sent me into town. You go on. You go in. Harold be glad to see you.”

“Here Trixie,” said Philip sternly.

The dog came yelping and bounding around them, Daisy squealed with fright and pleasure and somehow they were all on the route to the house, Eve carrying Daisy, and Philip and Trixie scrambling around her up some earthen bumps that had once been steps. The man came close behind them, smelling of the beer that he must have been drinking in the truck.

“Open it up, go ahead in,” he said. “Make your way through. You don’t mind it’s got a little untidy here? Mary’s in the Home, nobody to keep it tidied up like it used to be.”

Massive disorder was what they had to make their way through – the kind that takes years to accumulate. The bottom layer of it made up of chairs and tables and couches and perhaps a stove or two, with old bedclothes and newspapers and window shades and dead potted plants and ends of lumber and empty bottles and broken lighting fixtures and curtain rods piled on top of that, up to the ceiling in some places, blocking nearly all the light from outside. To make up for that, a light was burning by the inside door.

The man shifted the beer and got that door open, and shouted for Harold. It was hard to tell what sort of room they were in now – there were kitchen cupboards with the doors off the hinges, some cans on the shelves, but there were also a couple of cots with bare mattresses and rumpled blankets. The windows were so successfully covered up with furniture or hanging quilts that you could not tell where they were, and the smell was that of a junk store, a plugged sink, or maybe a plugged toilet, cooking and grease and cigarettes and human sweat and dog mess and unremoved garbage.

Nobody answered the shouts. Eve turned around – there was room to turn around here, as there hadn’t been in the porch – and said, “I don’t think we should—” but Trixie got in her way and the man ducked round her to bang on another door.

“Here he is,” he said – still at the top of his voice, though the door had opened. “Here’s Harold in here.” At the same time Trixie rushed forward, and another man’s voice said, “Fuck. Get that dog out of here.”

“Lady here wants to see some pictures,” the little man said. Trixie whined in pain – somebody had kicked her. Eve had no choice but to go on into the room.

This was a dining room. There was the heavy old dining-room table and the substantial chairs. Three men were sitting down, playing cards. The fourth man had got up to kick the dog. The temperature in the room was about ninety degrees.

“Shut the door, there’s a draft,” said one of the men at the table.

The little man hauled Trixie out from under the table and threw her into the outer room, then closed the door behind Eve and the children.

“Christ. Fuck,” said the man who had got up. His chest and arms were so heavily tattooed that he seemed to have purple or bluish skin. He shook one foot as if it hurt. Perhaps he had also kicked a table leg when he kicked Trixie.

Sitting with his back to the door was a young man with sharp narrow shoulders and a delicate neck. At least Eve assumed he was young, because he wore his hair in dyed golden spikes and had gold rings in his ears. He didn’t turn around. The man across from him was as old as Eve herself, and had a shaved head, a tidy gray beard, and bloodshot blue eyes. He looked at Eve without any friendliness but with some intelligence or comprehension, and in this he was unlike the tattooed man, who had looked at her as if she was some kind of hallucination that he had decided to ignore.

At the end of the table, in the host’s or the father’s chair, sat the man who had given the order to close the door, but who hadn’t looked up or otherwise paid any attention to the interruption. He was a large-boned, fat, pale man with sweaty brown curls, and as far as Eve could tell he was entirely naked. The tattooed man and the blond man were wearing jeans, and the gray-bearded man was wearing jeans and a checked shirt buttoned up to the neck and a string tie. There were glasses and bottles on the table. The man in the host’s chair – he must be Harold – and the gray-bearded man were drinking whiskey. The other two were drinking beer.

“I told her maybe there was pictures in the front but she couldn’t go in there you got that shut up,” the little man said.

Harold said, “You shut up.”

Eve said, “I’m really sorry.” There seemed to be nothing to do but go into her spiel, enlarging it to include staying at the village hotel as a little girl, drives with her mother, the pictures in the wall, her memory of them today, the gateposts, her obvious mistake, her apologies. She spoke directly to the graybeard, since he seemed the only one willing to listen or capable of understanding her. Her arm and shoulder ached from the weight of Daisy and from the tension which had got hold of her entire body. Yet she was thinking how she would describe this – she’d say it was like finding yourself in the middle of a Pinter play. Or like all her nightmares of a stolid, silent, hostile audience.

The graybeard spoke when she could not think of any further charming or apologetic thing to say. He said, “I don’t know. You’ll have to ask Harold. Hey. Hey Harold. Do you know anything about some pictures made out of broken glass?”

“Tell her when she was riding around looking at pictures I wasn’t even born yet,” said Harold, without looking up.

“You’re out of luck, lady,” said the graybeard.

The tattooed man whistled. “Hey you,” he said to Philip. “Hey kid. Can you play the piano?”

There was a piano in the room behind Harold’s chair. There was no stool or bench – Harold himself taking up most of the room between the piano and the table – and inappropriate things, such as plates and overcoats, were piled on top of it, as they were on every surface in the house.

“No,” said Eve quickly. “No he can’t.”

“I’m asking him,” the tattooed man said. “Can you play a tune?”

The graybeard said, “Let him alone.”

“Just asking if he can play a tune, what’s the matter with that?”

“Let him alone.”

“You see I can’t move until somebody moves the truck,” Eve said.

She thought, There is a smell of semen in this room.

Philip was mute, pressed against her side.

“If you could just move—” she said, turning and expecting to find the little man behind her. She stopped when she saw he wasn’t there, he wasn’t in the room at all, he had got out without her knowing when. What if he had locked the door?

She put her hand on the knob and it turned, the door opened with a little difficulty and a scramble on the other side of it. The little man had been crouched right there, listening.

Eve went out without speaking to him, out through the kitchen, Philip trotting along beside her like the most tractable little boy in the world. Along the narrow pathway on the porch, through the junk, and when they reached the open air she sucked it in, not having taken a real breath for a long time.

“You ought to go along down the road ask down at Harold’s cousin’s place,” the little man’s voice came after her. “They got a nice place. They got a new house, she keeps it beautiful. They’ll show you pictures or anything you want, they’ll make you welcome. They’ll sit you down and feed you, they don’t let nobody go away empty.”

He couldn’t have been crouched against the door all the time, because he had moved the truck. Or somebody had. It had disappeared altogether, been driven away to some shed or parking spot out of sight.

Eve ignored him. She got Daisy buckled in. Philip was buckling himself in, without having to be reminded. Trixie appeared from somewhere and walked around the car in a disconsolate way, sniffing at the tires.

Eve got in and closed the door, put her sweating hand on the key. The car started, she pulled ahead onto the gravel – a space that was surrounded by thick bushes, berry bushes she supposed, and old lilacs, as well as weeds. In places these bushes had been flattened by piles of old tires and bottles and tin cans. It was hard to think that things had been thrown out of that house, considering all that was left in it, but apparently they had. And as Eve swung the car around she saw, revealed by this flattening, some fragment of a wall, to which bits of whitewash still clung.

She thought she could see pieces of glass embedded there, glinting.

She didn’t slow down to look. She hoped Philip hadn’t noticed – he might want to stop. She got the car pointed towards the lane and drove past the dirt steps to the house. The little man stood there with both arms waving and Trixie was wagging her tail, roused from her scared docility sufficiently to bark farewell and chase them partway down the lane. The chase was only a formality; she could have caught up with them if she wanted to. Eve had had to slow down at once when she hit the ruts.

She was driving so slowly that it was possible, it was easy, for a figure to rise up out of the tall weeds on the passenger side of the car and open the door – which Eve had not thought of locking – and jump in.

It was the blond man who had been sitting at the table, the one whose face she had never seen.

“Don’t be scared. Don’t be scared anybody. I just wondered if I could hitch a ride with you guys, okay?”

It wasn’t a man or a boy; it was a girl. A girl now wearing a dirty sort of undershirt.

Eve said, “Okay.” She had just managed to hold the car in the track.

“I couldn’t ask you back in the house,” the girl said. “I went in the bathroom and got out the window and run out here. They probably don’t even know I’m gone yet. They’re boiled.” She took hold of a handful of the undershirt which was much too large for her and sniffed at it. “Stinks,” she said. “I just grabbed this of Harold’s, was in the bathroom. Stinks.”

Eve left the ruts, the darkness of the lane, and turned onto the ordinary road. “Jesus I’m glad to get out of there,” the girl said. “I didn’t know nothing about what I was getting into. I didn’t know even how I got there, it was night. It wasn’t no place for me. You know what I mean?”

“They seemed pretty drunk all right,” said Eve.

“Yeah. Well. I’m sorry if I scared you.”

“That’s okay.”

“If I hadn’t’ve jumped in I thought you wouldn’t stop for me. Would you?”

“I don’t know,” said Eve. “I guess I would have if it got through to me you were a girl. I didn’t really get a look at you before.”

“Yeah. I don’t look like much now. I look like shit now. I’m not saying I don’t like to party. I like to party. But there’s party and there’s party, you know what I mean?”

She turned in the seat and looked at Eve so steadily that Eve had to take her eyes from the road for a moment and look back. And what she saw was that this girl was much more drunk than she sounded. Her dark-brown eyes were glazed but held wide open, rounded with effort, and they had the imploring yet distant expression that drunks’ eyes get, a kind of last-ditch insistence on fooling you. Her skin was blotched in some places and ashy in others, her whole face crumpled with the effects of a mighty bingeing. She was a natural brunette – the gold spikes were intentionally and provocatively dark at the roots – and pretty enough, if you disregarded her present dinginess, to make you wonder how she had ever got mixed up with Harold and Harold’s crew. Her way of living and the style of the times must have taken fifteen or twenty natural pounds off her – but she wasn’t tall and she really wasn’t boyish. Her true inclination was to be a cuddly chunky girl, a darling dumpling.

“Herb was crazy bringing you in there like that,” she said. “He’s got a screw loose, Herb.”

Eve said, “I gathered that.”

“I don’t know what he does around there, I guess he works for Harold. I don’t think Harold uses him too good, neither.”

Eve had never believed herself to be attracted to women in a sexual way. And this girl in her soiled and crumpled state seemed unlikely to appeal to anybody. But perhaps the girl did not believe this possible – she must be so used to appealing to people. At any rate she slid her hand along Eve’s bare thigh, just getting a little way beyond the hem of her shorts. It was a practiced move, drunk as she was. To spread the fingers, to grasp flesh on the first try, would have been too much. A practiced, automatically hopeful move, yet so lacking in any true, strong, squirmy, comradely lust that Eve felt that the hand might easily have fallen short and caressed the car upholstery.

“I’m okay,” the girl said, and her voice, like the hand, struggled to put herself and Eve on a new level of intimacy. “You know what I mean? You understand me. Okay?”

“Of course,” said Eve briskly, and the hand trailed away, its tired whore’s courtesy done with. But it had not failed – not altogether. Blatant and halfhearted as it was, it had been enough to set some old wires twitching.

And the fact that it could be effective in any way at all filled Eve with misgiving, flung a shadow backwards from this moment over all the rowdy and impulsive as well as all the hopeful and serious, the more or less unrepented-of, couplings of her life. Not a real flare-up of shame, a sense of sin – just a dirty shadow. What a joke on her, if she started to hanker now after a purer past and a cleaner slate.

But it could be just that still, and always, she hankered after love.

She said, “Where is it you want to go?”

The girl jerked backwards, faced the road. She said, “Where you going? You live around here?” The blurred tone of seductiveness had changed, as no doubt it would change after sex, into a mean-sounding swagger.

“There’s a bus goes through the village,” Eve said. “It stops at the gas station. I’ve seen the sign.”

“Yeah but just one thing,” the girl said. “I got no money. See, I got away from there in such a hurry I never got to collect my money. So what use would it be me getting on a bus without no money?”