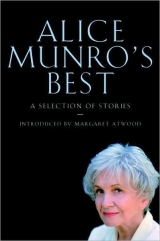

Текст книги "Alice Munro's Best"

Автор книги: Alice Munro

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

All this was what I wondered at the time. Later, when I knew more, at least about sex, I decided that Brian was Herb’s lover, and that Gladys really was trying to get attention from Herb, and that that was why Brian had humiliated her – with or without Herb’s connivance and consent. Isn’t it true that people like Herb – dignified, secretive, honorable people – will often choose somebody like Brian, will waste their helpless love on some vicious, silly person who is not even evil, or a monster, but just some importunate nuisance? I decided that Herb, with all his gentleness and carefulness, was avenging himself on us all – not just on Gladys but on us all – with Brian, and that what he was feeling when I studied his face must have been a savage and gleeful scorn. But embarrassment as well – embarrassment for Brian and for himself and for Gladys, and to some degree for all of us. Shame for all of us – that is what I thought then.

Later still, I backed off from this explanation. I got to a stage of backing off from the things I couldn’t really know. It’s enough for me now just to think of Herb’s face with that peculiar, stricken look; to think of Brian monkeying in the shade of Herb’s dignity; to think of my own mystified concentration on Herb, my need to catch him out, if I could ever get the chance, and then move in and stay close to him. How attractive, how delectable, the prospect of intimacy is, with the very person who will never grant it. I can still feel the pull of a man like that, of his promising and refusing. I would still like to know things. Never mind facts. Never mind theories, either.

When I finished my drink I wanted to say something to Herb. I stood beside him and waited for a moment when he was not listening to or talking with anyone else and when the increasingly rowdy conversation of the others would cover what I had to say.

“I’m sorry your friend had to go away.”

“That’s all right.”

Herb spoke kindly and with amusement, and so shut me off from any further right to look at or speak about his life. He knew what I was up to. He must have known it before, with lots of women. He knew how to deal with it.

Lily had a little more whisky in her mug and told how she and her best girlfriend (dead now, of liver trouble) had dressed up as men one time and gone into the men’s side of the beer parlor, the side where it said MEN ONLY, because they wanted to see what it was like. They sat in a corner drinking beer and keeping their eyes and ears open, and nobody looked twice or thought a thing about them, but soon a problem arose.

“Where were we going to go? If we went around to the other side and anybody seen us going into the ladies,’ they would scream bloody murder. And if we went into the men’s somebody’d be sure to notice we didn’t do it the right way. Meanwhile the beer was going through us like a bugger!”

“What you don’t do when you’re young!” Marjorie said.

Several people gave me and Morgy advice. They told us to enjoy ourselves while we could. They told us to stay out of trouble. They said they had all been young once. Herb said we were a good crew and had done a good job but he didn’t want to get in bad with any of the women’s husbands by keeping them there too late. Marjorie and Lily expressed indifference to their husbands, but Irene announced that she loved hers and that it was not true that he had been dragged back from Detroit to marry her, no matter what people said. Henry said it was a good life if you didn’t weaken. Morgan said he wished us all the most sincere Merry Christmas.

When we came out of the Turkey Barn it was snowing. Lily said it was like a Christmas card, and so it was, with the snow whirling around the streetlights in town and around the colored lights people had put up outside their doorways. Morgan was giving Henry and Irene a ride home in the truck, acknowledging age and pregnancy and Christmas. Morgy took a shortcut through the field, and Herb walked off by himself, head down and hands in his pockets, rolling slightly, as if he were on the deck of a lake boat. Marjorie and Lily linked arms with me as if we were old comrades.

“Let’s sing,” Lily said. “What’ll we sing?”

“‘We Three Kings’?” said Marjorie. “‘We Three Turkey Gutters’?”

“‘I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas.’”

“Why dream? You got it!”

So we sang.

THE MOONS OF JUPITER

I FOUND MY FATHER in the heart wing, on the eighth floor of Toronto General Hospital. He was in a semi-private room. The other bed was empty. He said that his hospital insurance covered only a bed in the ward, and he was worried that he might be charged extra.

“I never asked for a semi-private,” he said.

I said the wards were probably full.

“No. I saw some empty beds when they were wheeling me by.”

“Then it was because you had to be hooked up to that thing,” I said. “Don’t worry. If they’re going to charge you extra, they tell you about it.”

“That’s likely it,” he said. “They wouldn’t want those doohickeys set up in the wards. I guess I’m covered for that kind of thing.”

I said I was sure he was.

He had wires taped to his chest. A small screen hung over his head. On the screen a bright jagged line was continually being written. The writing was accompanied by a nervous electronic beeping. The behavior of his heart was on display. I tried to ignore it. It seemed to me that paying such close attention – in fact, dramatizing what ought to be a most secret activity – was asking for trouble. Anything exposed that way was apt to flare up and go crazy.

My father did not seem to mind. He said they had him on tranquillizers. You know, he said, the happy pills. He did seem calm and optimistic.

It had been a different story the night before. When I brought him into the hospital, to the emergency room, he had been pale and close-mouthed. He had opened the car door and stood up and said quietly, “Maybe you better get me one of those wheelchairs.” He used the voice he always used in a crisis. Once, our chimney caught on fire; it was on a Sunday afternoon and I was in the dining room pinning together a dress I was making. He came in and said in that same matter-of-fact, warning voice, “Janet. Do you know where there’s some baking powder?” He wanted it to throw on the fire. Afterwards he said, “I guess it was your fault – sewing on Sunday.”

I had to wait for over an hour in the emergency waiting room. They summoned a heart specialist who was in the hospital, a young man. He called me out into the hall and explained to me that one of the valves of my father’s heart had deteriorated so badly that there ought to be an immediate operation.

I asked him what would happen otherwise.

“He’d have to stay in bed,” the doctor said.

“How long?”

“Maybe three months.”

“I meant, how long would he live?”

“That’s what I meant too,” the doctor said.

I went to see my father. He was sitting up in bed in a curtained-off corner. “It’s bad, isn’t it?” he said. “Did he tell you about the valve?”

“It’s not as bad as it could be,” I said. Then I repeated, even exaggerated, anything hopeful the doctor had said. “You’re not in any immediate danger. Your physical condition is good, otherwise.”

“Otherwise,” said my father gloomily.

I was tired from the drive – all the way up to Dalgleish, to get him, and back to Toronto since noon – and worried about getting the rented car back on time, and irritated by an article I had been reading in a magazine in the waiting room. It was about another writer, a woman younger, better-looking, probably more talented than I am. I had been in England for two months and so I had not seen this article before, but it crossed my mind while I was reading that my father would have. I could hear him saying, Well, I didn’t see anything about you in Maclean’s. And if he had read something about me he would say, Well, I didn’t think too much of that write-up. His tone would be humorous and indulgent but would produce in me a familiar dreariness of spirit. The message I got from him was simple: Fame must be striven for, then apologized for. Getting or not getting it, you will be to blame.

I was not surprised by the doctor’s news. I was prepared to hear something of the sort and was pleased with myself for taking it calmly, just as I would be pleased with myself for dressing a wound or looking down from the frail balcony of a high building. I thought, Yes, it’s time; there has to be something, here it is. I did not feel any of the protest I would have felt twenty, even ten, years before. When I saw from my father’s face that he felt it – that refusal leapt up in him as readily as if he had been thirty or forty years younger – my heart hardened, and I spoke with a kind of badgering cheerfulness. “Otherwise is plenty,” I said.

THE NEXT DAY he was himself again.

That was how I would have put it. He said it appeared to him now that the young fellow, the doctor, might have been a bit too eager to operate. “A bit knife-happy,” he said. He was both mocking and showing off the hospital slang. He said that another doctor had examined him, an older man, and had given it as his opinion that rest and medication might do the trick.

I didn’t ask what trick.

“He says I’ve got a defective valve, all right. There’s certainly some damage. They wanted to know if I had rheumatic fever when I was a kid. I said I didn’t think so. But half the time then you weren’t diagnosed what you had. My father was not one for getting the doctor.”

The thought of my father’s childhood, which I always pictured as bleak and dangerous – the poor farm, the scared sisters, the harsh father – made me less resigned to his dying. I thought of him running away to work on the lake boats, running along the railway tracks, toward Goderich, in the evening light. He used to tell about that trip. Somewhere along the track he found a quince tree. Quince trees are rare in our part of the country; in fact, I have never seen one. Not even the one my father found, though he once took us on an expedition to look for it. He thought he knew the crossroad it was near, but we could not find it. He had not been able to eat the fruit, of course, but he had been impressed by its existence. It made him think he had got into a new part of the world.

The escaped child, the survivor, an old man trapped here by his leaky heart. I didn’t pursue these thoughts. I didn’t care to think of his younger selves. Even his bare torso, thick and white – he had the body of a working-man of his generation, seldom exposed to the sun – was a danger to me; it looked so strong and young. The wrinkled neck, the age-freckled hands and arms, the narrow, courteous head, with its thin gray hair and mustache, were more what I was used to.

“Now, why would I want to get myself operated on?” said my father reasonably. “Think of the risk at my age, and what for? A few years at the outside. I think the best thing for me to do is go home and take it easy. Give in gracefully. That’s all you can do, at my age. Your attitude changes, you know. You go through some mental changes. It seems more natural.”

“What does?” I said.

“Well, death does. You can’t get more natural than that. No, what I mean, specifically, is not having the operation.”

“That seems more natural?”

“Yes.”

“It’s up to you,” I said, but I did approve. This was what I would have expected of him. Whenever I told people about my father I stressed his independence, his self-sufficiency, his forbearance. He worked in a factory, he worked in his garden, he read history books. He could tell you about the Roman emperors or the Balkan wars. He never made a fuss.

JUDITH, MY YOUNGER daughter, had come to meet me at the Toronto Airport two days before. She had brought the boy she was living with, whose name was Don. They were driving to Mexico in the morning, and while I was in Toronto I was to stay in their apartment. For the time being, I live in Vancouver. I sometimes say I have my headquarters in Vancouver.

“Where’s Nichola?” I said, thinking at once of an accident or an overdose. Nichola is my older daughter. She used to be a student at the Conservatory, then she became a cocktail waitress, then she was out of work. If she had been at the airport, I would probably have said something wrong. I would have asked her what her plans were, and she would have gracefully brushed back her hair and said, “Plans?” – as if that was a word I had invented.

“I knew the first thing you’d say would be about Nichola,” Judith said.

“It wasn’t. I said hello and I–”

“We’ll get your bag,” Don said neutrally.

“Is she all right?”

“I’m sure she is,” said Judith, with a fabricated air of amusement. “You wouldn’t look like that if I was the one who wasn’t here.”

“Of course I would.”

“You wouldn’t. Nichola is the baby of the family. You know, she’s four years older than I am.”

“I ought to know.”

Judith said she did not know where Nichola was exactly. She said Nichola had moved out of her apartment (that dump!) and had actually telephoned (which is quite a deal, you might say, Nichola phoning) to say she wanted to be incommunicado for a while but she was fine.

“I told her you would worry,” said Judith more kindly on the way to their van. Don walked ahead carrying my suitcase. “But don’t. She’s all right, believe me.”

Don’s presence made me uncomfortable. I did not like him to hear these things. I thought of the conversations they must have had, Don and Judith. Or Don and Judith and Nichola, for Nichola and Judith were sometimes on good terms. Or Don and Judith and Nichola and others whose names I did not even know. They would have talked about me. Judith and Nichola comparing notes, relating anecdotes; analyzing, regretting, blaming, forgiving. I wished I’d had a boy and a girl. Or two boys. They wouldn’t have done that. Boys couldn’t possibly know so much about you.

I did the same thing at that age. When I was the age Judith is now I talked with my friends in the college cafeteria or, late at night, over coffee in our cheap rooms. When I was the age Nichola is now I had Nichola herself in a carry-cot or squirming in my lap, and I was drinking coffee again on all the rainy Vancouver afternoons with my one neighborhood friend, Ruth Boudreau, who read a lot and was bewildered by her situation, as I was. We talked about our parents, our childhoods, though for some time we kept clear of our marriages. How thoroughly we dealt with our fathers and mothers, deplored their marriages, their mistaken ambitions or fear of ambition, how competently we filed them away, defined them beyond any possibility of change. What presumption.

I looked at Don walking ahead. A tall ascetic-looking boy, with a St. Francis cap of black hair, a precise fringe of beard. What right did he have to hear about me, to know things I myself had probably forgotten? I decided that his beard and hairstyle were affected.

Once, when my children were little, my father said to me, “You know those years you were growing up – well, that’s all just a kind of a blur to me. I can’t sort out one year from another.” I was offended. I remembered each separate year with pain and clarity. I could have told how old I was when I went to look at the evening dresses in the window of Benbow’s Ladies’ Wear. Every week through the winter a new dress, spotlit – the sequins and tulle, the rose and lilac, sapphire, daffodil – and me a cold worshipper on the slushy sidewalk. I could have told how old I was when I forged my mother’s signature on a bad report card, when I had measles, when we papered the front room. But the years when Judith and Nichola were little, when I lived with their father – yes, blur is the word for it. I remember hanging out diapers, bringing in and folding diapers; I can recall the kitchen counters of two houses and where the clothesbasket sat. I remember the television programs – Popeye the Sailor, The Three Stooges, Funorama. When Funorama came on it was time to turn on the lights and cook supper. But I couldn’t tell the years apart. We lived outside Vancouver in a dormitory suburb: Dormir, Dormer, Dormouse – something like that. I was sleepy all the time then; pregnancy made me sleepy, and the night feedings, and the west coast rain falling. Dark dripping cedars, shiny dripping laurel; wives yawning, napping, visiting, drinking coffee, and folding diapers; husbands coming home at night from the city across the water. Every night I kissed my homecoming husband in his wet Burberry and hoped he might wake me up; I served up meat and potatoes and one of the four vegetables he permitted. He ate with a violent appetite, then fell asleep on the living-room sofa. We had become a cartoon couple, more middle-aged in our twenties than we would be in middle age.

Those bumbling years are the years our children will remember all their lives. Corners of the yards I never visited will stay in their heads.

“Did Nichola not want to see me?” I said to Judith.

“She doesn’t want to see anybody, half the time,” she said. Judith moved ahead and touched Don’s arm. I knew that touch – an apology, an anxious reassurance. You touch a man that way to remind him that you are grateful, that you realize he is doing for your sake something that bores him or slightly endangers his dignity. It made me feel older than grandchildren would to see my daughter touch a man – a boy – this way. I felt her sad jitters, could predict her supple attentions. My blunt and stocky, blond and candid child. Why should I think she wouldn’t be susceptible, that she would always be straightforward, heavy-footed, self-reliant? Just as I go around saying that Nichola is sly and solitary, cold, seductive. Many people must know things that would contradict what I say.

In the morning Don and Judith left for Mexico. I decided I wanted to see somebody who wasn’t related to me, and who didn’t expect anything in particular from me. I called an old lover of mine, but his phone was answered by a machine: “This is Tom Shepherd speaking. I will be out of town for the month of September. Please record your message, name, and phone number.”

Tom’s voice sounded so pleasant and familiar that I opened my mouth to ask him the meaning of this foolishness. Then I hung up. I felt as if he had deliberately let me down, as if we had planned to meet in a public place and then he hadn’t shown up. Once, he had done that, I remembered.

I got myself a glass of vermouth, though it was not yet noon, and I phoned my father.

“Well, of all things,” he said. “Fifteen more minutes and you would have missed me.”

“Were you going downtown?”

“Downtown Toronto.”

He explained that he was going to the hospital. His doctor in Dalgleish wanted the doctors in Toronto to take a look at him, and had given him a letter to show them in the emergency room.

“Emergency room?” I said.

“It’s not an emergency. He just seems to think this is the best way to handle it. He knows the name of a fellow there. If he was to make me an appointment, it might take weeks.”

“Does your doctor know you’re driving to Toronto?” I said.

“Well, he didn’t say I couldn’t.”

The upshot of this was that I rented a car, drove to Dalgleish, brought my father back to Toronto, and had him in the emergency room by seven o’clock that evening.

Before Judith left I said to her, “You’re sure Nichola knows I’m staying here?”

“Well, I told her,” she said.

Sometimes the phone rang, but it was always a friend of Judith’s.

“WELL, IT LOOKS like I’m going to have it,” my father said. This was on the fourth day. He had done a complete turnaround overnight. “It looks like I might as well.”

I didn’t know what he wanted me to say. I thought perhaps he looked to me for a protest, an attempt to dissuade him.

“When will they do it?” I said.

“Day after tomorrow.”

I said I was going to the washroom. I went to the nurses’ station and found a woman there who I thought was the head nurse. At any rate, she was gray-haired, kind, and serious-looking.

“My father’s having an operation the day after tomorrow?” I said.

“Oh, yes.”

“I just wanted to talk to somebody about it. I thought there’d been a sort of decision reached that he’d be better not to. I thought because of his age.”

“Well, it’s his decision and the doctor’s.” She smiled at me without condescension. “It’s hard to make these decisions.”

“How were his tests?”

“Well, I haven’t seen them all.”

I was sure she had. After a moment she said, “We have to be realistic. But the doctors here are very good.”

When I went back into the room my father said, in a surprised voice, “Shore-less seas.”

“What?” I said. I wondered if he had found out how much, or how little, time he could hope for. I wondered if the pills had brought on an untrustworthy euphoria. Or if he had wanted to gamble. Once, when he was talking to me about his life, he said, “The trouble was I was always afraid to take chances.”

I used to tell people that he never spoke regretfully about his life, but that was not true. It was just that I didn’t listen to it. He said that he should have gone into the Army as a tradesman – he would have been better off. He said he should have gone on his own, as a carpenter, after the war. He should have got out of Dalgleish. Once, he said, “A wasted life, eh?” But he was making fun of himself, saying that, because it was such a dramatic thing to say. When he quoted poetry too, he always had a scoffing note in his voice, to excuse the showing-off and the pleasure.

“Shoreless seas,” he said again. “‘Behind him lay the gray Azores, / Behind the Gates of Hercules; / Before him not the ghost of shores, / Before him only shoreless seas.’ That’s what was going through my head last night. But do you think I could remember what kind of seas? I could not. Lonely seas? Empty seas? I was on the right track but I couldn’t get it. But there now when you came into the room and I wasn’t thinking about it at all, the word popped into my head. That’s always the way, isn’t it? It’s not all that surprising. I ask my mind a question. The answer’s there, but I can’t see all the connections my mind’s making to get it. Like a computer. Nothing out of the way. You know, in my situation the thing is, if there’s anything you can’t explain right away, there’s a great temptation to – well, to make a mystery out of it. There’s a great temptation to believe in – You know.”

“The soul?” I said, speaking lightly, feeling an appalling rush of love and recognition.

“Oh, I guess you could call it that. You know, when I first came into this room there was a pile of papers here by the bed. Somebody had left them here – one of those tabloid sort of things I never looked at. I started reading them. I’ll read anything handy. There was a series running in them on personal experiences of people who had died, medically speaking – heart arrest, mostly – and had been brought back to life. It was what they remembered of the time when they were dead. Their experiences.”

“Pleasant or un-?” I said.

“Oh, pleasant. Oh, yes. They’d float up to the ceiling and look down on themselves and see the doctors working on them, on their bodies. Then float on further and recognize some people they knew who had died before them. Not see them exactly but sort of sense them. Sometimes there would be a humming and sometimes a sort of – what’s that light that there is or color around a person?”

“Aura?”

“Yes. But without the person. That’s about all they’d get time for; then they found themselves back in the body and feeling all the mortal pain and so on – brought back to life.”

“Did it seem – convincing?”

“Oh, I don’t know. It’s all in whether you want to believe that kind of thing or not. And if you are going to believe it, take it seriously, I figure you’ve got to take everything else seriously that they print in those papers.”

“What else do they?”

“Rubbish – cancer cures, baldness cures, bellyaching about the younger generation and the welfare bums. Tripe about movie stars.”

“Oh, yes. I know.”

“In my situation you have to keep a watch,” he said, “or you’ll start playing tricks on yourself.” Then he said, “There’s a few practical details we ought to get straight on,” and he told me about his will, the house, the cemetery plot. Everything was simple.

“Do you want me to phone Peggy?” I said. Peggy is my sister. She is married to an astronomer and lives in Victoria.

He thought about it. “I guess we ought to tell them,” he said finally. “But tell them not to get alarmed.”

“All right.”

“No, wait a minute. Sam is supposed to be going to a conference the end of this week, and Peggy was planning to go along with him. I don’t want them wondering about changing their plans.”

“Where is the conference?”

“Amsterdam,” he said proudly. He did take pride in Sam, and kept track of his books and articles. He would pick one up and say, “Look at that, will you? And I can’t understand a word of it!” in a marvelling voice that managed nevertheless to have a trace of ridicule.

“Professor Sam,” he would say. “And the three little Sams.” This is what he called his grandsons, who did resemble their father in braininess and in an almost endearing pushiness – an innocent energetic showing-off. They went to a private school that favored old-fashioned discipline and started calculus in Grade 5. “And the dogs,” he might enumerate further, “who have been to obedience school. And Peggy…”

But if I said, “Do you suppose she has been to obedience school too?” he would play the game no further. I imagine that when he was with Sam and Peggy he spoke of me in the same way – hinted at my flightiness just as he hinted at their stodginess, made mild jokes at my expense, did not quite conceal his amazement (or pretended not to conceal his amazement) that people paid money for things I had written. He had to do this so that he might never seem to brag, but he would put up the gates when the joking got too rough. And of course I found later, in the house, things of mine he had kept – a few magazines, clippings, things I had never bothered about.

Now his thoughts travelled from Peggy’s family to mine. “Have you heard from Judith?” he said.

“Not yet.”

“Well, it’s pretty soon. Were they going to sleep in the van?”

“Yes.”

“I guess it’s safe enough, if they stop in the right places.”

I knew he would have to say something more and I knew it would come as a joke.

“I guess they put a board down the middle, like the pioneers?”

I smiled but did not answer.

“I take it you have no objections?”

“No,” I said.

“Well, I always believed that too. Keep out of your children’s business. I tried not to say anything. I never said anything when you left Richard.”

“What do you mean, ‘said anything’? Criticize?”

“It wasn’t any of my business.”

“No.”

“But that doesn’t mean I was pleased.”

I was surprised – not just at what he said but at his feeling that he had any right, even now, to say it. I had to look out the window and down at the traffic to control myself.

“I just wanted you to know,” he added.

A long time ago, he said to me in his mild way, “It’s funny. Richard when I first saw him reminded me of what my father used to say. He’d say if that fellow was half as smart as he thinks he is, he’d be twice as smart as he really is.”

I turned to remind him of this, but found myself looking at the line his heart was writing. Not that there seemed to be anything wrong, any difference in the beeps and points. But it was there.

He saw where I was looking. “Unfair advantage,” he said.

“It is,” I said. “I’m going to have to get hooked up too.”

We laughed, we kissed formally; I left. At least he hadn’t asked me about Nichola, I thought.

THE NEXT AFTERNOON I didn’t go to the hospital, because my father was having some more tests done, to prepare for the operation. I was to see him in the evening instead. I found myself wandering through the Bloor Street dress shops, trying on clothes. A preoccupation with fashion and my own appearance had descended on me like a raging headache. I looked at the women in the street, at the clothes in the shops, trying to discover how a transformation might be made, what I would have to buy. I recognized this obsession for what it was but had trouble shaking it. I’ve had people tell me that waiting for life-or-death news they’ve stood in front of an open refrigerator eating anything in sight – cold boiled potatoes, chili sauce, bowls of whipped cream. Or have been unable to stop doing crossword puzzles. Attention narrows in on something – some distraction – grabs on, becomes fanatically serious. I shuffled clothes on the racks, pulled them on in hot little changing rooms in front of cruel mirrors. I was sweating; once or twice I thought I might faint. Out on the street again, I thought I must remove myself from Bloor Street, and decided to go to the museum.

I remembered another time, in Vancouver. It was when Nichola was going to kindergarten and Judith was a baby. Nichola had been to the doctor about a cold, or maybe for a routine examination, and the blood test revealed something about her white blood cells – either that there were too many of them or that they were enlarged. The doctor ordered further tests, and I took Nichola to the hospital for them. Nobody mentioned leukemia but I knew, of course, what they were looking for. When I took Nichola home I asked the babysitter who had been with Judith to stay for the afternoon and I went shopping. I bought the most daring dress I ever owned, a black silk sheath with some laced-up arrangement in front. I remembered that bright spring afternoon, the spike-heeled shoes in the department store, the underwear printed with leopard spots.

I also remembered going home from St. Paul’s Hospital over the Lions Gate Bridge on the crowded bus and holding Nichola on my knee. She suddenly recalled her baby name for bridge and whispered to me, “Whee – over the whee.” I did not avoid touching my child – Nichola was slender and graceful even then, with a pretty back and fine dark hair – but realized I was touching her with a difference, though I did not think it could ever be detected. There was a care – not a withdrawal exactly but a care – not to feel anything much. I saw how the forms of love might be maintained with a condemned person but with the love in fact measured and disciplined, because you have to survive. It could be done so discreetly that the object of such care would not suspect, any more than she would suspect the sentence of death itself. Nichola did not know, would not know. Toys and kisses and jokes would come tumbling over her; she would never know, though I worried that she would feel the wind between the cracks of the manufactured holidays, the manufactured normal days. But all was well. Nichola did not have leukemia. She grew up – was still alive, and possibly happy. Incommunicado.