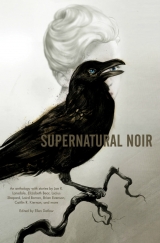

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

As I walked back to the house, I tried to think of where he would have asked to meet her. I pictured all the places I’d been to in the past few weeks. An image of Ms. Berkley’s map came to mind, the one of town with the red dots and the triangles, east and west. I’d not found a triangle point to the west, and as I considered that, I recalled the point I had found in the east, the symbol spray-painted on the trunk of an old car up on blocks. It came to me—say that one didn’t count because it wasn’t on a building, connected to the ground. That was a fake. Maybe he knew somehow Ms. Berkley would notice the symbols and he wanted to throw her off.

Then it struck me: what if there was a third symbol in the west I just didn’t see? I tried to picture the map as the actual streets it represented and figure where the center of a western triangle would be. At first it seemed way too complicated, just a jumble of frustration, but I took a few deep breaths, and, recalling the streets I’d walked before, realized the spot must be somewhere in the park across the street from Maya’s Newsstand. It was a hike, and I knew I had to pace myself, but the fact that I’d figured out Lionel’s twists and turns gave me a burst of energy. What I really wanted was to tell Ms. Berkley how I’d thought it through. Then I realized she might already be dead.

Something instinctively drew me toward the gazebo. It was a perfect center for a magician’s prison. The moonlight was on the lake. I thought I heard them talking, saw their shadows sitting on the bench, smelled the smoke of Ducados, but when I took the steps and leaned over to catch my breath, I realized it was all in my mind. The place was empty and still. The geese called from out on the lake. I sat down on the bench and lit a cigarette. Only when I resigned myself to just returning to the house, it came to me I had one more option: to find the last point of the western triangle.

I knew it was a long shot at night, looking without a flashlight for something I couldn’t find during the day. My only consolation was that since Lionel hadn’t taken Ms. Berkley to the center of his triangle, he might not intend to use her as his victim.

I was exhausted, and although I set out from the gazebo jogging toward my best guess as to where the last point was, I was soon walking. The street map of town with the red triangles would flash momentarily in my memory and then disappear. I went up a street that was utterly dark, and the wind followed me. From there, I turned and passed a row of closed factory buildings. The symbol could have been anywhere, hiding in the dark. Finally, there was a cross street, and I walked down a block of row homes, some boarded, some with bars on the windows. That path led to an industrial park. Beneath a dim streetlight, I stopped and tried to picture the map, but it was no use. I was totally lost. I gave up and turned back in the direction I thought Ms. Berkley’s house would be.

One block outside the industrial park, I hit a street of old four-story apartment buildings. The doors were off the hinges, and the moonlight showed no reflection in the shattered windows. A neighborhood of vacant lots and dead brick giants. Halfway down the block, hoping to find a left turn, I just happened to look up and see an unbroken window, yellow lamplight streaming out. From where I stood, I could only see the ceiling of the room, but faint silhouettes moved across it. I took out the gun. There was no decent reason why I thought it was them, but I felt drawn to the place as if under a spell.

I took the stone steps of the building, and when I tried the door, it pushed open. I thought this was strange, but I figured he might have left it ajar for Ms. Berkley. Inside, the foyer was so dark and there was no light on the first landing. I found the first step by inching forward and feeling around with my foot. The last thing I needed was three flights of stairs. I tried to climb without a sound, but the planks creaked unmercifully. “If they don’t hear me coming,” I thought, “they’re both dead.”

As I reached the fourth floor, I could hear noises coming from the room. It sounded like two people were arguing and wrestling around. Then I distinctly heard Ms. Berkley cry out. I lunged at the door, cracked it on the first pounce and busted it in with the second. Splinters flew, and the chain lock ripped out with a pop. I stumbled into the room, the gun pointing forward, completely out of breath. It took me a second to see what was going on.

There they were, in a bed beneath the window in the opposite corner of the room, naked, frozen by my intrusion, her legs around his back. Ms. Berkley scooted up and quickly wrapped the blanket around herself, leaving old Lionel out in the cold. He jumped up quick, dick flopping, and got into his boxers.

“What the hell,” I whispered.

“Go home, Thomas,” she said.

“You’re coming with me,” I said.

“I can handle this,” she said.

“Who’s after you?” I said to Lionel. “For what?”

He took a deep breath. “Phantoms more cruel than you can imagine, my boy. I lived my young life recklessly, like you, and its mistakes have multiplied and hounded me ever since.”

“You’re a loser,” I said and it sounded so stupid. Especially when it struck me that Lionel might have been old, but he looked pretty strong.

“Sorry, son,” he said and drew that long knife from a scabbard on the nightstand next to the bed. “It’s time to sever ties.”

“Run,” said Ms. Berkley.

I thought, “Fuck this guy,” and pulled out the gun.

Ms. Berkley jumped on Lionel, but he shrugged her off with a sharp push that landed her back on the bed. “This one’s not running,” he said. “I can tell.”

I was stunned for a moment by Ms. Berkley’s nakedness. But as he advanced a step, I raised the gun and told him, “Drop the knife.”

He said, “Be careful; you’re hurting it.”

At first his words didn’t register, but then, in my hand, instead of a gun, I felt a frail wriggling thing with a heartbeat. I released my grasp, and a bat flew up to circle around the ceiling. In the same moment, I heard the gun hit the wooden floor and knew he’d tricked me with magic.

He came toward me slowly, and I whipped off two of my T-shirts and wrapped them around my right forearm. He sliced the air with the blade a few times as I crouched down and circled away from him. He lunged fast as a snake, and I got caught against a dresser. He cut me on the stomach and the right shoulder. The next time he came at me, I kicked a footstool in front of him and managed a punch to the side of his head. Lionel came back with a half dozen more slices, each marking me. The T-shirts on my arm were in shreds, as was the one I wore.

I kept watching that knife, and that’s how he got me, another punch to the jaw worse than the one in the station parking lot. I stumbled backward and he followed with the blade aimed at my throat. What saved me was that Ms. Berkley grabbed him from behind. He stopped to push her off again, and I caught my balance and took my best shot to the right side of his face. The punch scored, he fell backward into the wall, and the knife flew in the air. I tried to catch it as it fell but only managed to slice my fingers. I picked it up by the handle and when I looked, Lionel was steamrolling toward me again.

“Thomas,” yelled Ms. Berkley from where she’d landed. I was stunned, and automatically pushed the weapon forward into the bulk of the charging magician. He stopped in his tracks, teetered for a second, and fell back onto his ass. He sat there on the rug, legs splayed, with that big knife sticking out of his stomach. Blood seeped around the blade and puddled in front of him.

Ms. Berkley was next to me, leaning on my shoulder. “Pay attention,” she said.

I snapped out of it and looked down at Lionel. He was sighing more than breathing and staring at the floor.

“If he dies,” said Ms. Berkley, “you inherit the spell of the Last Triangle.”

“That’s right,” Lionel said. Blood came from his mouth with the words. “Wherever you are at dawn, that will be the center of your world.” He laughed. “For the rest of your life you will live in a triangle within the rancid town of Fishmere.”

Ms. Berkley found the gun and picked it up. She went to the bed and grabbed one of the pillows.

“Is that true?” I said and started to panic.

Lionel nodded, laughing. Ms. Berkley took up the gun again and then wrapped the pillow around it. She walked over next to Lionel, crouched down, and touched the pillow to the side of his head.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

Ms. Berkley squinted one eye and steadied her left arm with her right hand while keeping the pillow in place.

“What else?” said Lionel, spluttering blood bubbles. “What needs to be done.”

The pillow muffled the sound of the shot somewhat as feathers flew everywhere. Lionel dropped onto his side without magic, the hole in his head smoking. I wasn’t afraid anyone would hear. There wasn’t another soul for three blocks. Ms. Berkley checked his pulse. “The Last Triangle is mine now,” she said. “I have to get home by dawn.” She got dressed while I stood in the hallway.

I don’t remember leaving Lionel’s building, or passing the park or Maya’s Newsstand. We were running through the night, across town, as the sky lightened in the distance. Four blocks from home, Ms. Berkley gave out and started limping. I picked her up and, still running, carried her the rest of the way. We were in the kitchen, the tea whistle blowing, when the birds started to sing and the sun came up.

She poured the tea for us and said, “I thought I could talk Lionel out of his plan, but he wasn’t the same person anymore. I could see the magic’s like a drug; the more you use it, the more it pushes you out of yourself and takes over.”

“Was he out to kill me or you?” I asked.

“He was out to get himself killed. I’d promised to do the job for him before you showed up. He knew we were onto him and he tried to fool us with the train-station scam, but once he heard my voice that night, he said he knew he couldn’t go through with it. He just wanted to see me once more, and then I was supposed to cut his throat.”

“You would have killed him?” I said.

“I did.”

“You know, before I knifed him?”

“He told me the phantoms and fetches that were after him knew where he was, and it was only a matter of days before they caught up with him.”

“What was it exactly he did?”

“He wouldn’t say, but he implied that it had to do with loving me. And I really think he thought he did.”

“What do you think?” I asked.

Ms. Berkley interrupted me. “You’ve got to get out of town,” she said. “When they find Lionel’s body, you’ll be one of the usual suspects, what with your wandering around drinking beer and smoking pot in public.”

“Who told you that?” I said.

“Did I just fall off the turnip truck yesterday?”

Ms. Berkley went to her office and returned with a roll of cash for me. I didn’t even have time to think about leaving, to miss my cot and the weights, and the meals. The cab showed up and we left. She had her map of town with the triangles on it and had already drawn a new one—its center, her kitchen. We drove for a little ways and then she told the cab driver to pull over and wait. We were in front of a closed-down gas station on the edge of town. She got out and I followed her.

“I paid the driver to take you two towns over to Willmuth. There’s a bus station there. Get a ticket and disappear,” she said.

“What about you? You’re stuck in the triangle.”

“I’m bounded in a nutshell,” she said.

“Why’d you take the spell?”

“You don’t need it. You just woke up. I have every confidence that I’ll be able to figure a way out of it. It’s amazing what you can find on the Internet.”

“A magic spell?” I said.

“Understand this,” she said. “Spells are made to be broken.” She stepped closer and reached her hands to my shoulders. I leaned down. She kissed me on the forehead. “Not promises, though,” she said and turned away, heading home.

“Ms. Berkley,” I called after her.

“Stay clean,” she yelled without looking.

Back in the cab, I said, “Willmuth,” and leaned against the window. The driver started the car, and we sailed through an invisible boundary, into the world.

–

Jeffrey Ford is the author of the novels The Physiognomy, Memoranda, The Beyond, The Portrait of Mrs. Charbuque, The Girl in the Glass, and The Shadow Year. His short fiction has been published in three collections: The Fantasy Writer’s Assistant, The Empire of Ice Cream, and The Drowned Life. His fiction has won the World Fantasy Award, the Nebula Award, the Edgar Allan Poe Award, and the Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and two sons and teaches literature and writing at Brookdale Community College.

| THE CARRION GODS IN THEIR HEAVEN |

| THE CARRION GODS IN THEIR HEAVEN |

Laird Barron

–

The leaves were turning.

Lorna fueled the car at a mom-and-pop gas station in the town of Poger Rock, population 190. Poger Rock comprised a forgotten, moribund collection of buildings tucked into the base of a wooded valley a stone’s throw south of Olympia. The station’s marquee was badly peeled and she couldn’t decipher its title. A tavern called Mooney’s occupied a gravel island half a block down, across the two-lane street from the post office and the grange. Next to a dumpster, a pair of mongrel dogs were locked in coitus, patiently facing opposite directions, Dr. Doolittle’s Pushmi-pullyu for the twenty-first century. Other than vacant lots overrun by bushes and alder trees and a lone antiquated traffic light at the intersection that led out of town—either toward Olympia, or deeper into cow country—there wasn’t much else to look at. She hobbled in to pay and ended up grabbing a few extra supplies—canned peaches and fruit cocktail, as there wasn’t any refrigeration at the cabin. She snagged three bottles of bourbon gathering dust on a low shelf.

The clerk noticed her folding crutch and the soft cast on her left leg. She declined his offer to carry her bags. After she loaded the Subaru, she ventured into the tavern and ordered a couple rounds of tequila. The tavern was dim and smoky and possessed a frontier vibe, with antique flintlocks over the bar, and stuffed and mounted deer heads staring from the walls. A great black wolf snarled atop a dais near the entrance. The bartender watched her drain the shots raw. He poured her another on the house and said, “You’re staying at the Haugstad place, eh?”

She hesitated, the glass partially raised, then set the drink on the counter and limped away without answering. She assayed the long, treacherous drive up to the cabin, chewing over the man’s question, the morbid implication of his smirk. She got the drift. Horror movies and pulp novels made the conversational gambit infamous—life imitating art. Was she staying at the Haugstad place indeed. Like hell she’d take that bait. The townsfolk were strangers to her and she wondered how the bartender knew where she lived. Obviously, the hills had eyes.

Two weeks prior, Lorna had fled into the wilderness to an old hunting cabin, the so-called Haugstad place, with her lover Miranda. Miranda was the reason she’d discovered the courage to leave her husband Bruce, the reason he grabbed a fistful of Lorna’s hair and threw her down a flight of concrete stairs in the parking garage of Sea-Tac airport. That was the second time Lorna had tried to escape with their daughter Orillia. Sweet Orillia, eleven years old next month, was safe in Florida with relatives. Lorna missed her daughter, but slept better knowing she was far from Bruce’s reach. He wasn’t interested in going after the child; at least not as his first order of business.

Bruce was a vengeful man, and Lorna feared him the way she might fear a hurricane, a volcano, a flood. His rages overwhelmed and obliterated his impulse control. Bruce was a force of nature, all right, and capable of far worse than breaking her leg. He owned a gun and a collection of knives, had done time years ago for stabbing somebody during a fight over a gambling debt. He often got drunk and sat in his easy chair cleaning his pistol or sharpening a large, cruel-looking blade he called an Arkansas toothpick.

So, it came to this: Lorna and Miranda shacked up in the mountains while Lorna’s estranged husband, free on bail, awaited trial back in Seattle. Money wasn’t a problem—Bruce made plenty as a manager at a lumber company, and Lorna had helped herself to a healthy portion of it when she headed for the hills.

Both women were loners by necessity—or device, as the case might be—who’d met at a cocktail party thrown by one of Bruce’s colleagues and clicked on contact. Lorna hadn’t worked since her stint as a movie-theater clerk during college—Bruce had insisted she stay home and raise Orillia, and when Orillia grew older, he dropped his pretenses and punched Lorna in the jaw after she pressed the subject of getting a job, beginning a career. She’d dreamed of going to grad school for a degree in social work.

Miranda was a semiretired artist, acclaimed in certain quarters and much in demand for her wax sculptures. She cheerfully set up a mini studio in the spare bedroom, strictly to keep her hand in. Photography was her passion of late, and she’d brought along several complicated and expensive cameras. She was also the widow of a once-famous sculptor. Between her work and her husband’s royalties, she wasn’t exactly rich, but not exactly poor, either. They’d survive a couple of months “roughing it.” Miranda suggested they consider it a vacation, an advance celebration of “Brucifer’s” (her pet name for Lorna’s soon-to-be ex) impending stint as a guest of King County Jail.

She’d secured the cabin through a labyrinthine network of connections. Miranda’s second (or was it third?) cousin gave them a ring of keys and a map to find the property. It sat in the mountains, ten miles from civilization amid high timber and a tangle of abandoned logging roads. The driveway was cut into a steep hillside—a hundred-yard-long dirt track hidden by masses of brush and trees. The perfect bolthole.

Bruce wouldn’t find them here, in the catbird’s seat overlooking nowhere.

–

Lorna arrived home a few minutes before nightfall. Miranda came to the porch and waved. She was tall, her hair long and burnished auburn, her skin dusky and unblemished. Lorna thought her beautiful—lush and ripe, vaguely Rubenesque. A contrast to Lorna’s own paleness, her angular, sinewy build. She thought it amusing that their personalities reflected their physiognomies—Miranda tended to be placid and yielding and sweetly melancholy, while Lorna was all sharp edges.

Miranda helped bring in the groceries. She’d volunteered to drive into town and fetch them herself, but Lorna refused, and the reason why went unspoken, although it loomed large. A lot more than her leg needed healing. Bruce had done the shopping, paid the bills, made every decision for thirteen torturous years. Not all at once, but gradually, until he crushed her, smothered her, with his so-called love. That was over. A little more pain and suffering in the service of emancipation—figuratively and literally—following a lost decade seemed appropriate.

The Haugstad cabin was practically a fossil and possessed of a dark history that Miranda hinted at but coyly refused to disclose. It was in solid repair for a building constructed in the 1920s—on the cozy side, even: thick slab walls and a mossy shake roof. Two bedrooms, a pantry, a loft, a cramped toilet and bath, and a living room with a kitchenette tucked in the corner. The cellar’s trapdoor was concealed inside the pantry. She had no intention of going down there. She hated spiders and all the other creepy-crawlies sure to infest that wet and lightless space. Nor did she like the tattered bearskin rug before the fireplace, nor the oil painting of a hunter in buckskins stalking along a ridge beneath a twilit sky, nor a smaller portrait of a stag with jagged horns in menacing silhouette atop a cliff, also at sunset. Lorna detested the idea of hunting, preferred not to ponder where the chicken in chicken soup came from, much less the fate of cattle. These artifacts of minds and philosophies so divergent from her own were disquieting.

There were a few modern renovations. A portable generator provided electricity to power the plumbing and lights. No phone, however. Not that it mattered—her cell reception was passable despite the rugged terrain. The elevation and eastern exposure also enabled the transistor radio to capture a decent signal.

Miranda raised an eyebrow when she came across the bottles of Old Crow. She stuck them in a cabinet without comment. They made a simple pasta together with peaches on the side and a glass or three of wine for dessert. Later, they relaxed near the fire. Conversation lapsed into a comfortable silence until Lorna chuckled upon recalling the bartender’s portentous question, which seemed inane rather than sinister now that she was half-drunk and drowsing in her lover’s arms. Miranda asked what was so funny, and Lorna told her about the tavern incident.

“Man alive, I found something weird today,” Miranda said. She’d stiffened when Lorna described shooting tequila. Lorna’s drinking was a bone of contention. She’d hit the bottle when Orillia went into first grade, leaving her alone at the house for the majority of too many lonely days. At first it’d been innocent enough: A nip or two of cooking sherry, the occasional glass of wine during the soaps, then the occasional bottle of wine, then the occasional bottle of Maker’s Mark or Johnnie Walker, and finally, the bottle was open and in her hand five minutes after Orillia skipped to the bus and the cork didn’t go back in until five minutes before her little girl came home. Since she and Miranda became an item, she’d striven to restrict her boozing to social occasions, dinner, and the like. But sweet Jesus, fuck. At least she hadn’t broken down and started smoking again.

“Where’d you go?” Lorna said.

“That trail behind the woodshed. I wanted some photographs. Being cooped up in here is driving me a teensy bit bonkers.”

“So, how weird was it?”

“Maybe weird isn’t quite the word. Gross. Gross is more accurate.”

“You’re killing me.”

“That trail goes a long way. I think deer use it as a path because it’s really narrow but well beaten. We should hike to the end one of these days, see how far it goes. I’m curious where it ends.”

“Trails don’t end; they just peter out. We’ll get lost and spend the winter gnawing bark like the Donners.”

“You’re so morbid!” Miranda laughed and kissed Lorna’s ear. She described crossing a small clearing about a quarter mile along the trail. At the far end was a stand of Douglas fir, and she didn’t notice the tree house until she stopped to snap a few pictures. The tree house was probably as old as the cabin; its wooden planks were bone yellow where they peeked through moss and branches. The platform perched about fifteen feet off the ground, and a ladder was nailed to the backside of a tree . . .

“You didn’t climb the tree,” Lorna said.

Miranda flexed her scraped and bruised knuckles. “Yes, I climbed that tree, all right.” The ladder was very precarious and the platform itself so rotted, sections of it had fallen away. Apparently, for no stronger reason than boredom, she risked life and limb to clamber atop the platform and investigate.

“It’s not a tree house,” Lorna said. “You found a hunter’s blind. The hunter sits on the platform, camouflaged by the branches. Eventually, some poor, hapless critter comes by, and blammo! Sadly, I’ve learned a lot from Bruce’s favorite cable-television shows. What in the heck compelled you to scamper around in a deathtrap in the middle of the woods? You could’ve gotten yourself in a real fix.”

“That occurred to me. My foot went through in one spot and I almost crapped my pants. If I got stuck I could scream all day and nobody would hear me. The danger was worth it, though.”

“Well, what did you find? Some moonshine in mason jars? D. B. Cooper’s skeleton?”

“Time for the reveal!” Miranda extricated herself from Lorna and went and opened the door, letting in a rush of cold night air. She returned with what appeared to be a bundle of filthy rags and proceeded to unroll them.

Lorna realized her girlfriend was presenting an animal hide. The fur had been sewn into a crude cape or cloak, beaten and weathered from great age, and shriveled along the hem. The head was that of some indeterminate predator—possibly a wolf or coyote. Whatever the species, the creature was a prize specimen. Despite the cloak’s deteriorated condition, she could imagine it draped across the broad shoulders of a Viking berserker or an Indian warrior. She said, “You realize that you just introduced several colonies of fleas, ticks, and lice into our habitat with that wretched thing.”

“Way ahead of you, baby. I sprayed it with bleach. Cooties were crawling all over. Isn’t it neat?”

“It’s horrifying,” Lorna said. Yet she couldn’t look away as Miranda held it at arm’s length so the pelt gleamed dully in the firelight. What was it? Who’d worn it, and why? Was it a garment to provide mere warmth, or to blend with the surroundings? The painting of the hunter was obscured by shadows, but she thought of the man in buckskin sneaking along, looking for something to kill, a throat to slice. Her hand went to her throat.

“This was hanging from a peg. I’m kinda surprised it’s not completely ruined, what with the elements. Funky, huh? A Daniel Boone–era accessory.”

“Gives me the creeps.”

“The creeps? It’s just a fur.”

“I don’t dig fur. Fur is dead. Man.”

“You’re a riot. I wonder if it’s worth money.”

“I really doubt that. Who cares? It’s not ours.”

“Finders keepers,” Miranda said. She held the cloak against her bosom as if she were measuring a dress. “Rowr! I’m a wild woman. Better watch yourself tonight!” She’d drunk enough wine to be in the mood for theater. “Scandinavian legends say to wear the skin of a beast is to become the beast. Haugstad fled to America in 1910, cast out from his community. There was a series of unexplained murders back in the homeland, and other unsavory deeds, all of which pointed to his doorstep. People in his village swore he kept a bundle of hides in a storehouse, that he donned them and became something other than a man, that it was he who tore apart a family’s cattle, that it was he who slaughtered a couple of boys hunting rabbits in the field, that it was he who desecrated graves and ate of the flesh of the dead during lean times. So, he left just ahead of a pitchfork-wielding mob. He built this cabin and lived a hermit’s life. Alas, his dark past followed. Some of the locals in Poger Rock got wind of the old scandals. One of the town drunks claimed he saw the trapper turn into a wolf, and nobody laughed as hard as one might expect. Haugstad got blamed whenever a cow disappeared, when the milk went sour, you name it. Then, over the course of ten years or so a long string of loggers and ranchers vanished. The natives grew restless, and it was the scene in Norway all over again.”

“What happened to him?”

“He wandered into the mountains one winter and never returned. Distant kin took over this place, lived here off and on the last thirty or forty years. Folks still remember, though.” Miranda made an exaggerated face and waggled her fingers. “Booga-booga!”

Lorna smiled, but she was repulsed by the hide, and unsettled by Miranda’s flushed cheeks, her loopy grin. Her lover’s playfulness wasn’t amusing her as it might’ve on another night. She said, “Toss that wretched skin outside, would you? Let’s hit the sack. I’m exhausted.”

“Exhausted, eh? Now is my chance to take full advantage of you.” Miranda winked as she stroked the hide. Instead of heading for the front door, she took her prize to the spare bedroom and left it there. She came back and embraced Lorna. Her eyes were too bright. The wine was strong on her breath. “Told you it was cool. God knows what else we’ll find if we look sharp.”

–

They made fierce love. Miranda was much more aggressive than her custom. The pain in Lorna’s knee built from a small flame to a white blaze of agony and her orgasm only registered as spasms in her thighs and shortness of breath, pleasure eclipsed entirely by suffering. Miranda didn’t notice the tears on Lorna’s cheeks, the frantic nature of her moans. When it ended, she kissed Lorna on the mouth, tasting of musk and salt, and something indefinably bitter. She collapsed and was asleep within seconds.

Lorna lay propped by pillows, her hand tangled in Miranda’s hair. The faint yellow shine of a three-quarter moon peeked over the ridgeline across the valley and beamed through the window at the foot of the bed. She could tell it was cold because their breaths misted the glass. A wolf howled and she flinched, the cry arousing a flutter of primordial dread in her breast. She waited until Miranda’s breathing steadied, then crept away. She put on Miranda’s robe and grabbed a bottle of Old Crow and a glass and poured herself a dose, and sipped it before the main window in the living room.

Thin, fast-moving clouds occasionally crossed the face of the moon, and its light pulsed and shadows reached like claws across the silvery landscape of rocky hillocks and canyons and stands of firs and pine. The stars burned a finger width above the crowns of the adjacent peaks. The land fell away into deeper shadow, a rift of darkness uninterrupted by a solitary flicker of man-made light. She and Miranda weren’t welcome; the cabin and its former inhabitants hadn’t been, either, despite persisting like ticks bored into the flank of a dog. The immensity of the void intimidated her, and for a moment she almost missed Bruce and the comparative safety of her suburban home, the gilded cage, even the bondage. She blinked, angry at this lapse into the bad old way of thinking, and drank the whiskey. “I’m not a damned whipped dog.” She didn’t bother pouring but had another pull directly from the bottle.