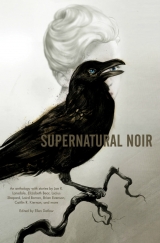

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

The stairs had ended in a wide, circular area. The roof was flat, low, the walls no more than shadowy suggestions. Just-Call-Me-Bill’s flashlight had roamed the floor, picked out a symbol incised in the rock at their feet: a rough circle, the diameter of a manhole cover, broken at about eight o’clock. Its circumference was stained black, its interior a map of dark brown splotches. Hold this, he had said, passing her the flashlight, which had occupied her for the two or three seconds it took him to remove a plastic baggie from one of the pockets of his safari vest. When Vasquez had directed the light at him, he was dumping the bag’s contents in his right hand, tugging at the plastic with his left to pull it away from the dull red wad. The stink of blood and meat on the turn had made her step back. Steady, specialist. The bag’s contents had landed inside the broken circle with a heavy, wet smack. Vasquez had done her best not to study it too closely.

A sound, the scrape of bare flesh dragging over stone, from behind and to her left, had spun Vasquez around, the flashlight held out to blind, her sidearm freed and following the light’s path. This section of the curving wall opened in a black arch like the top of an enormous throat. For a moment, that space had been full of a great, pale figure. Vasquez had had a confused impression of hands large as tires grasping either side of the arch, a boulder of a head, its mouth gaping amidst a frenzy of beard, its eyes vast, idiot. It was scrambling toward her; she didn’t know where to aim—

And then Mr. White had been standing in the archway, dressed in the white linen suit that somehow always seemed stained, even though no discoloration was visible on any of it. He had not blinked at the flashlight beam stabbing his face; nor had he appeared to judge Vasquez’s gun pointing at him of much concern. Muttering an apology, Vasquez had lowered gun and light immediately. Mr. White had ignored her, strolling across the round chamber to the foot of the stairs, which he had climbed quickly. Just-Call-Me-Bill had hurried after, a look on his bland face that Vasquez took for amusement. She had brought up the rear, sweeping the flashlight over the floor as she reached the lowest step. The broken circle had been empty, except for a red smear that shone in the light.

That she had momentarily hallucinated, Vasquez had not once doubted. Things with Mr. White already had raced past what even Just-Call-Me-Bill had shown them, and however effective his methods, Vasquez was afraid that she—that all of them had finally gone too far, crossed over into truly bad territory. Combined with a mild claustrophobia, it had caused her to fill the dark space with a nightmare. However reasonable that explanation, the shape with which her mind had replaced Mr. White had plagued her. Had she seen the devil stepping forward on his goat’s feet, one red hand using his pitchfork to balance himself, it would have made more sense than that giant form. It was as if her subconscious was telling her more about Mr. White than she understood. Prior to that trip, Vasquez had not been at ease around the man who never seemed to speak so much as to have spoken, so that you knew what he’d said even though you couldn’t remember hearing him saying it. After, she gave him a still-wider berth.

Ahead, the Eiffel Tower swept up into the sky. Vasquez had seen it from a distance, at different points along her and Buchanan’s journey from their hotel toward the Seine, but the closer she drew to it, the less real it seemed. It was as if the very solidity of the beams and girders weaving together were evidence of their falseness. I am seeing the Eiffel Tower, she told herself. I am actually looking at the goddamn Eiffel Tower.

“Here you are,” Buchanan said. “Happy?”

“Something like that.”

The great square under the tower was full of tourists—from the sound of it, the majority of them groups of Americans and Italians. Nervous men wearing untucked shirts over their jeans flitted from group to group—street vendors, Vasquez realized, each one carrying an oversized ring strung with metal replicas of the tower. A pair of gendarmes, their hands draped over the machine guns slung high on their chests, let their eyes roam the crowd while they carried on a conversation. In front of each of the tower’s legs, lines of people waiting for the chance to ascend it doubled and redoubled back on themselves, enormous fans misting water over them. Taking Buchanan’s arm, Vasquez steered them toward the nearest fan. Eyebrows raised, he tilted his head toward her.

“Ambient noise,” she said.

“Whatever.”

Once they were close enough to the fan’s propeller drone, Vasquez leaned into Buchanan. “Go with this,” she said.

“You’re the boss.” Buchanan gazed up, a man debating whether he wanted to climb that high.

“I’ve been thinking,” Vasquez said. “Plowman’s plan is shit.”

“Oh?” He pointed at the tower’s first level, three hundred feet above.

Nodding, Vasquez said, “We approach Mr. White, and he’s just going to agree to come with us to the elevator.”

Buchanan dropped his hand. “Well, we do have our . . . persuaders. How do you like that? Was it cryptic enough? Or should I have said guns?”

Vasquez smiled as if Buchanan had uttered an endearing remark. “You really think Mr. White is going to be impressed by a pair of .22s?”

“A bullet’s a bullet. Besides,” Buchanan returned her smile, “isn’t the plan for us not to have to use the guns? Aren’t we relying on him remembering us?”

“It’s not like we were BFFs. If it were me, and I wanted the guy, and I had access to Stillwater’s resources, I wouldn’t be wasting my time on a couple of convicted criminals. I’d put together a team and go get him. Besides, twenty grand apiece for catching up to someone outside his hotel room, passing a couple of words with him, then escorting him to an elevator: tell me that doesn’t sound too good to be true.”

“You know the way these big companies work: they’re all about throwing money around. Your problem is, you’re still thinking like a soldier.”

“Even so, why spend it on us?”

“Maybe Plowman feels bad about everything. Maybe this is his way of making it up to us.”

“Plowman? Seriously?”

Buchanan shook his head. “This isn’t that complicated.”

Vasquez closed her eyes. “Humor me.” She leaned her head against Buchanan’s chest.

“What have I been doing?”

“We’re a feint. While we’re distracting Mr. White, Plowman’s up to something else.”

“Like?”

“Maybe Mr. White has something in his room; maybe we’re occupying him while Plowman’s retrieving it.”

“You know there are easier ways for Plowman to steal something.”

“Maybe we’re keeping Mr. White in place so Plowman can pull a hit on him.”

“Again, there are simpler ways to do that that would have nothing to do with us. You knock on the guy’s door, he opens it, pow.”

“What if we’re supposed to get caught in the crossfire?”

“You bring us all the way here just to kill us?”

“Didn’t you say big companies like to spend money?”

“But why take us out in the first place?”

Vasquez raised her head and opened her eyes. “How many of the people who knew Mr. White are still in circulation?”

“There’s Just-Call-Me-Bill—”

“You think. He’s CIA. We don’t know what happened to him.”

“Okay. There’s you, me, Plowman—”

“Go on.”

Buchanan paused, reviewing, Vasquez knew, the fates of the three other guards who’d assisted Mr. White with his work in the Closet. Long before news had broken about Mahbub Ali’s death, Lavalle had sat on the edge of his bunk, placed his gun in his mouth, and squeezed the trigger. Then, when the shit storm had started, Maxwell, on patrol, had been stabbed in the neck by an insurgent who’d targeted only him. Finally, in the holding cell awaiting his court-martial, Ruiz had taken advantage of a lapse in his jailers’ attention to strip off his pants, twist them into a rope, and hang himself from the top bunk of his cell’s bunkbed. His guards had cut him down in time to save his life, but Ruiz had deprived his brain of oxygen for sufficient time to leave him a vegetable. When Buchanan spoke, he said, “Coincidence.”

“Or conspiracy.”

“Goddamn it.” Buchanan pulled free of Vasquez, and headed for the long, rectangular park that stretched behind the tower, speed walking. His legs were sufficiently long that she had to jog to catch up to him. Buchanan did not slacken his pace, continuing his straight line up the middle of the park, through the midst of bemused picnickers. “Jesus Christ,” Vasquez called, “will you slow down?”

He would not. Heedless of oncoming traffic, Buchanan led her across a pair of roads that traversed the park. Horns blaring, tires screaming, cars swerved around them. At this rate, Vasquez thought, Plowman’s motives won’t matter. Once they were safely on the grass again, she sped up until she was beside him, then reached high on the underside of Buchanan’s right arm, not far from the armpit, and pinched as hard as she could.

“Ow! Shit!” Yanking his arm up and away, Buchanan stopped. Rubbing his skin, he said, “What the hell, Vasquez?”

“What the hell are you doing?”

“Walking. What did it look like?”

“Running away.”

“Fuck you.”

“Fuck you, you candy-ass pussy.”

Buchanan’s eyes flared.

“I’m trying to work this shit out so we can stay alive. You’re so concerned about seeing your son, maybe you’d want to help me.”

“Why are you doing this?” Buchanan said. “Why are you fucking with my head? Why are you trying to fuck this up?”

“I’m—”

“There’s nothing to work out. We’ve got a job to do; we do it; we get the rest of our money. We do the job well, there’s a chance Stillwater’ll add us to their payroll. That happens—I’m making that kind of money—I hire myself a pit bull of a lawyer and sic him on fucking Heidi. You want to live in goddamn Paris, you can eat a croissant for breakfast every morning.”

“You honestly believe that.”

“Yes, I do.”

Vasquez held his gaze, but who was she kidding? She could count on one finger the number of stare downs she’d won. Her arms, legs, everything felt suddenly, incredibly heavy. She looked at her watch. “Come on,” she said, starting in the direction of the Avenue de la Bourdonnais. “We can catch a cab.”

–

III

Plowman had insisted they meet him at an airport cafй before they set foot outside de Gaulle. At the end of those ten minutes, which had consisted of Plowman asking details of their flight and instructing them how to take the RUR to the Metro to the stop nearest their hotel, he had passed Vasquez a card for a restaurant, where, he had said, the three of them would reconvene at 3:00 p.m. local time to review the evening’s plans. Vasquez had been relieved to see Plowman seated at a table outside the cafй. Despite the ten thousand dollars gathering interest in her checking account, the plane ticket that had been FedExed to her apartment, followed by the receipt for four nights’ stay at the Hфtel Resnais, she had been unable to shake the sense that none of this was as it appeared, that it was the setup to an elaborate joke whose punch line would come at her expense. Plowman’s solid form, dressed in a black suit whose tailored lines announced the upward shift in his pay grade, had confirmed that everything he had told her the afternoon he had sought her out at Andersen’s farm had been true.

Or true enough to quiet momentarily the misgivings that had whispered ever louder in her ears the last two weeks, to the point that she had held her cell open in her left hand, the piece of paper with Plowman’s number on it in her right, ready to call him and say she was out, he could have his money back, she hadn’t spent any of it. During the long, hot train ride from the airport to the Metro station, when Buchanan had complained about Plowman not letting them out of his sight, treating them like goddamn kids, Vasquez had found an explanation on her lips. It’s probably the first time he’s run an operation like this, she had said. He wants to be sure he dots all his i’s and crosses all his t’s. Buchanan had harrumphed, but it was true: Plowman obsessed over the minutiae; it was one of the reasons he’d been in charge of their detail at the prison. Until the shit had buried the fan, that attentiveness had seemed to forecast his steady climb up the chain of command. At his court-martial, however, his enthusiasm for exact strikes on prisoner nerve clusters, his precision in placing arm restraints so that a prisoner’s shoulders would not dislocate when he was hoisted off the floor by his bonds, and his speed in obtaining the various surgical and dental instruments Just-Call-Me-Bill requested had been counted liabilities rather than assets, and he had been the only one of their group to serve substantial time at Leavenworth—ten months.

Still, the Walther that Vasquez had requested had been waiting where Plowman had promised it would be, wrapped with an extra clip in a waterproof bag secured inside the tank of her hotel room’s toilet. A thorough inspection had reassured her that all was in order with the gun, its ammunition. If he were setting her up, would Plowman have wanted to arm her? Her proficiency at the target range had been well known, and while she hadn’t touched a gun since her discharge, she had no doubts of her ability. Tucked within the back of her jeans, draped by her blouse, the pistol was easily accessible.

That’s assuming, of course, that Plowman’s even there tonight. But the caution was a formality. Plowman being Plowman, there was no way he was not going to be at Mr. White’s hotel. Was there any need for him to have made the trip to West Virginia, to have tracked her to Andersen’s farm, to have sought her out in the far barns, where she’d been using a high-pressure hose to sluice pig shit into gutters? An e-mail, a phone call would have sufficed. Such methods, however, would have left too much outside Plowman’s immediate control, and since he appeared able to dunk his bucket into a well of cash deeper than any she’d known, he had decided to find Vasquez and speak to her directly. (He’d done the same with Buchanan, she’d learned on the flight over, tracking him to the suburb of Chicago where he’d been shift manager at Hardee’s.) If the man had gone to such lengths to persuade them to take the job, if he had been there to meet them at Charles de Gaulle and was waiting for them even now, as their taxi crossed the Seine and headed toward the Champs Йlysйes, was there any chance he wouldn’t be present later on?

Of course, he wouldn’t be alone. Plowman would have the reassurance of God only knew how many Stillwater employees—which was to say, mercenaries (no doubt, heavily armed and armored)—backing him up. Vasquez hadn’t had much to do with the company’s personnel; they tended to roost closer to the center of Kabul, where the high-value targets they guarded huddled. Iraq: that was where Stillwater’s boot print was the deepest. From what Vasquez had heard, the former soldiers riding the reinforced Lincoln Navigators through Baghdad not only made about five times what they had in the military; they followed rules of engagement that were, to put it mildly, less robust. While Paris was as far east as she was willing to travel, she had to admit, the prospect of that kind of money made Baghdad, if not appealing, at least less unappealing.

And what would Dad have to say to that? No matter that his eyes were failing, the center of his vision consumed by macular degeneration; her father had lost none of his passion for the news, employing a standing magnifier to aid him as he pored over the day’s New York Times and Washington Post, sitting in his favorite chair listening to All Things Considered on WVPN, even venturing online to the BBC using the computer whose monitor settings she had adjusted for him before she’d deployed. Her father would not have missed the reports of Stillwater’s involvement in several incidents in Iraq that were less shootouts than turkey shoots, not to mention the ongoing Congressional inquiry into their policing of certain districts of post–Katrina and Rita New Orleans, as well as an event in upstate New York last summer, when one of their employees had taken a camping trip that had left two of his three companions dead under what could best be described as suspicious circumstances. She could hear his words, heavy with the accent that had accreted as he’d aged: Was this why I suffered in the Villa Grimaldi? So my daughter could join the Caravana de la Muerte? The same question he’d asked her the first night she’d returned home.

All the same, it wasn’t as if his opinion of her was going to drop any further. If I’m damned, she thought, I might as well get paid for it.

That said, she was in no hurry to certify her ultimate destination, which returned her to the problem of Plowman and his plan. You would have expected the press of the .22 against the small of her back to have been reassuring, but instead, it only emphasized her sense of powerlessness, as if Plowman were so confident, so secure, he could allow her whatever firearm she wanted.

The cab turned onto the Champs Йlysйes. Ahead, the Arc de Triomphe squatted in the distance. Another monument to cross off the list.

–

IV

The restaurant whose card Plowman had handed her was located on one of the side streets about halfway to the arch; Vasquez and Buchanan departed their cab at the street’s corner and walked the hundred yards to a door flanked by man-sized plaster Chinese dragons. Buchanan brushed past the black-suited host and his welcome; smiling and murmuring, “Pardonnez, nous avons un rendez-vous iзi,” Vasquez pursued him into the dim interior. Up a short flight of stairs, Buchanan strode across a floor that glowed with pale light—glass, Vasquez saw, thick squares suspended over shimmering aquamarine. A carp the size of her forearm darted underneath her, and she realized that she was standing on top of an enormous, shallow fish tank, brown and white and orange carp racing one another across its bottom, jostling the occasional slower turtle. With one exception, the tables supported by the glass were empty. Too late, Vasquez supposed, for lunch, and too early for dinner. Or maybe the food here wasn’t that good.

His back to the far wall, Plowman was seated at a table directly in front of her. Already, Buchanan was lowering himself into a chair opposite him. Stupid, Vasquez thought at the expanse of his unguarded back. Her boots clacked on the glass. She moved around the table to sit beside Plowman, who had exchanged the dark suit in which he’d greeted them at de Gaulle for a tan jacket over a cream shirt and slacks. His outfit caught the light filtering from below them and held it in as a dull sheen. A metal bowl filled with dumplings was centered on the table mat before him; to its right, a slice of lemon floated at the top of a glass of clear liquid. Plowman’s eyebrow raised as she settled beside him, but he did not comment on her choice; instead, he said, “You’re here.”

Vasquez’s yes was overridden by Buchanan’s “We are, and there are some things we need cleared up.”

Vasquez stared at him. Plowman said, “Oh?”

“That’s right,” Buchanan said. “We’ve been thinking, and this plan of yours doesn’t add up.”

“Really.” The tone of Plowman’s voice did not change.

“Really,” Buchanan nodded.

“Would you care to explain to me exactly how it doesn’t add up?”

“You expect Vasquez and me to believe you spent all this money so the two of us can have a five-minute conversation with Mr. White?”

Vasquez flinched.

“There’s a little bit more to it than that.”

“We’re supposed to persuade him to walk twenty feet with us to an elevator.”

“Actually, it’s seventy-four feet, three inches.”

“Whatever.” Buchanan glanced at Vasquez. She looked away. To the wall to her right, water chuckled down a series of small rock terraces and through an opening in the floor into the fish tank.

“No, not whatever, Buchanan. Seventy-four feet, three inches,” Plowman said. “This is why the biggest responsibility you confront each day is lifting the fry basket out of the hot oil when the buzzer tells you to. You don’t pay attention to the little things.”

The host was standing at Buchanan’s elbow, his hands clasped over a pair of long menus. Plowman nodded at him, and he passed the menus to Vasquez and Buchanan. Inclining toward them, the host said, “May I bring you drinks while you decide your order?”

His eyes on the menu, Buchanan said, “Water.”

“Moi aussi,” Vasquez said. “Merзi.”

“Nice accent,” Plowman said when the host had left.

“Thanks.”

“I don’t think I realized you speak French.”

Vasquez shrugged. “Wasn’t any call for it, was there?”

“Anything else?” Plowman said. “Spanish?”

“I understand more than I can speak.”

“Your folks were from—where, again?”

“Chile,” Vasquez said. “My dad. My mom’s American, but her parents were from Argentina.”

“That’s useful to know.”

“For when Stillwater hires her,” Buchanan said.

“Yes,” Plowman answered. “The company has projects underway in a number of places where fluency in French and Spanish would be an asset.”

“Such as?”

“One thing at a time,” Plowman said. “Let’s get through tonight, first, and then you can worry about your next assignment.”

“And what’s that going to be,” Buchanan said, “another twenty K to walk someone to an elevator?”

“I doubt it’ll be anything so mundane,” Plowman said. “I also doubt it’ll pay as little as twenty thousand.”

“Look,” Vasquez started to say, but the host had returned with their water. Once he deposited their glasses on the table, he withdrew a pad and pen from his jacket pocket and took Buchanan’s order of crispy duck and Vasquez’s of steamed dumplings. After he had retrieved the menus and gone, Plowman turned to Vasquez and said, “You were saying?”

“It’s just—what Buchanan’s trying to say is, it’s a lot, you know? If you’d offered us, I don’t know, say five hundred bucks apiece to come here and play escort, that still would’ve been a lot, but it wouldn’t—I mean, twenty thousand dollars, plus the airfare, the hotel, the expense account. It seems too much for what you’re asking us to do. Can you understand that?”

Plowman shook his head yes. “I can. I can understand how strange it might appear to offer this kind of money for this length of service, but . . .” He raised his drink to his lips. When he lowered his arm, the glass was half-drained. “Mr. White is . . . to say he’s high value doesn’t begin to cover it. The guy’s been around—he’s been around. Talk about a font of information: the stuff this guy’s forgotten would be enough for a dozen careers. What he remembers will give whoever can get him to share it with them permanent tactical advantage.”

“No such thing,” Buchanan said. “No matter how much the guy says he knows—”

“Yes, yes,” Plowman held up his hand like a traffic cop. “Trust me. He’s high value.”

“But won’t the spooks—what’s Just-Call-Me-Bill have to say about this?” Vasquez said.

“Bill’s dead.”

Simultaneously, Buchanan said, “Huh,” and Vasquez, “What? How?”

“I don’t know. When my bosses green-lighted me for this, Bill was the first person I thought of. I wasn’t sure if he was still with the agency, so I did some checking around. I couldn’t find out much—goddamn spooks keep their mouths shut—but I was able to determine that Bill was dead. It sounded like it might’ve been that chopper crash in Helmand, but that’s a guess. To answer your question, Vasquez, Bill didn’t have a whole lot to say.”

“Shit,” Buchanan said.

“Okay,” Vasquez exhaled. “Okay. Was he the only one who knew about Mr. White?”

“I find it hard to believe he was,” Plowman said, “but thus far, no one’s nibbled at any of the bait I’ve left out. I’m surprised; I’ll admit it. But it makes our job that much simpler, so I’m not complaining.”

“All right,” Vasquez said, “but the money—”

His eyes alight, Plowman leaned forward. “To get my hands on Mr. White, I would have paid each of you ten times as much. That’s how important this operation is. Whatever we have to shell out now is nothing compared to what we’re going to gain from this guy.”

“Now you tell us,” Buchanan said.

Plowman smiled and relaxed back. “Well, the bean counters do appreciate it when you can control costs.” He turned to Vasquez. “Well? Have your concerns been addressed?”

“Hey,” Buchanan said, “I was the one asking the questions.”

“Please,” Plowman said. “I was in charge of you, remember? Whatever your virtues, Buchanan, original thought is not among them.”

“What about Mr. White?” Vasquez said. “Suppose he doesn’t want to come with you?”

“I don’t imagine he will,” Plowman said. “Nor do I expect him to be terribly interested in assisting us once he is in our custody. That’s okay.” Plowman picked up one of the chopsticks alongside his plate, turned it in his hand, and jabbed it into a dumpling. He lifted the dumpling to his mouth; momentarily, Vasquez pictured a giant bringing its teeth together on a human head. While he chewed, Plowman said, “To be honest, I hope the son of a bitch is feeling especially stubborn. Because of him, I lost everything that was good in my life. Because of that fucker, I did time in prison—fucking prison.” Plowman swallowed, speared another dumpling. “Believe me when I say, Mr. White and I have a lot of quality time coming.”

Beneath them, a half-dozen carp that had been floating lazily scattered.

–

V

Buchanan was all for finding Mr. White’s hotel and parking themselves in its lobby. “What?” Vasquez said. “Behind a couple of newspapers?” Stuck in traffic on what should have been the short way to the Concorde Opйra, where Mr. White had the junior suite, their cab was full of the reek of exhaust, the low rumble of the cars surrounding them.

“Sure, yeah, that’d work.”

“Jesus—and I’m the one who’s seen too many movies?”

“What?” Buchanan said.

“Number one, at this rate, it’ll be at least six before we get there. How many people sit around reading the day’s paper at night? The whole point of the news is, it’s new.”

“Maybe we’re on vacation.”

“Doesn’t matter. We’ll still stick out. And number two, even if the lobby’s full of tourists holding newspapers up in front of their faces, Plowman’s plan doesn’t kick in until eleven. You telling me no one’s going to notice the same two people sitting there, doing the same thing, for five hours? For all we know, Mr. White’ll see us on his way out and coming back.”

“Once again, Vasquez, you’re overthinking this. People don’t see what they don’t expect to see. Mr. White isn’t expecting us in the lobby of his plush hotel; ergo, he won’t notice us there.”

“Are you kidding? This isn’t people. This is Mr. White.”

“Get a grip. He eats, shits, and sleeps, same as you and me.”

For the briefest of instants, the window over Buchanan’s shoulder was full of the enormous face Vasquez had glimpsed (hallucinated) in the caves under the prison. Not for the first time, she was struck by the crudeness of the features, as if a sculptor had hurriedly struck out the approximation of a human visage on a piece of rock already formed to suggest it.

Taking her silence as further disagreement, Buchanan sighed and said, “All right. Tell you what: a big, tony hotel, there’s gotta be all kinds of stores around it, right? Long as we don’t go too far, we’ll do some shopping.”

“Fine,” Vasquez said. When Buchanan had settled back in his seat, she said, “So. You satisfied with Plowman’s answers?”

“Aw, no, not this again . . .”

“I’m just asking a question.”

“No, what you’re asking is called a leading question, as in, leading me to think that Plowman didn’t really say anything to us, and we don’t know anything more now than we did before our meeting.”

“You learned something from that?”

Buchanan nodded. “You bet I did. I learned that Plowman has a hard-on for Mr. White the size of your fucking Eiffel Tower, from which I deduce that anyone who helps him satisfy himself stands to benefit enormously.” As the cab lurched forward, Buchanan said, “Am I wrong?”

“No,” Vasquez said. “It’s—”

“What? What is it, now?”

“I don’t know.” She looked out her window at the cars creeping along beside them.

“Well, that’s helpful.”

“Forget it.”

For once, Buchanan chose not to pursue the argument. Beyond the car to their right, Vasquez watched men and women walking past the windows of ground-level businesses, tech stores and clothing stores and a bookstore and an office whose purpose she could not identify. Over their wrought-iron balconies, the windows of the apartments above showed the late-afternoon sky, its blue deeper, as if hardened by a day of the sun’s baking. Because of him, I lost everything that was good in my life. Because of that fucker, I did time in prison—fucking prison. Plowman’s declaration sounded in her ears. Insofar as the passion on his face authenticated his words, and so the purpose of their mission, his brief monologue should have been reassuring. And yet, and yet . . .

In the moment before he drove his fist into a prisoner’s solar plexus, Plowman’s features, distorted and red from the last hour’s interrogation, would relax. The effect was startling, as if a layer of heavy makeup had melted off his skin. In the subsequent stillness of his face, Vasquez initially had read Plowman’s actual emotion, a clinical detachment from the pain he was preparing to inflict that was based in his utter contempt for the man standing in front of him. While his mouth would stretch with his screams to the prisoner to Get up! Get the fuck up! in the second after his blow had dropped the man to the concrete floor, and while his mouth and eyes would continue to express the violence his fists and boots were concentrating on the prisoner’s back, his balls, his throat, there would be other moments, impossible to predict, when, as he was shuffle-stepping away from a kick to the prisoner’s kidney, Plowman’s face would slip into that nonexpression, and Vasquez would think that she had seen through to the real man.

Then, the week after Plowman had brought Vasquez onboard what he had named the White Detail, she’d found herself sitting through a Steven Seagal double feature—not her first or even tenth choice for a way to pass three hours, but it beat lying on her bunk thinking, Why are you so shocked? You knew what Plowman was up to—everyone knows. An hour into The Patriot, the vague sensation that had been nagging at her from Seagal’s first scene crystallized into recognition: that the blank look with which the actor met every ebb and flow in the drama was the same as the one that Vasquez had caught on Plowman’s face—was, she understood, its original. For the remainder of that film and the duration of the next (Belly of the Beast), Vasquez had stared at the undersized screen in a kind of horrified fascination, unable to decide which was worse: to be serving under a man whose affect suggested a sociopath, or to be serving under a man who was playing the lead role in a private movie.