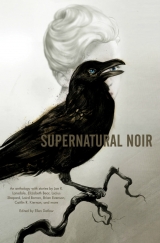

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

How many days after that had Just-Call-Me-Bill arrived? No more than two, she was reasonably sure. He had come, he told the White Detail, because their efforts with particularly recalcitrant prisoners had not gone unnoticed, and his superiors judged it would be beneficial for him to share his knowledge of enhanced interrogation techniques with them—and no doubt, they had some things to teach him. His back ramrod straight, his face alight, Plowman had barked his enthusiasm for their collaboration.

After that, it had been learning the restraints that would cause the prisoner maximum discomfort, expose him (or occasionally, her) to optimum harm. It was hoisting the prisoner off the ground first without dislocating his shoulders, then with. Waterboarding, yes, together with the repurposing of all manner of daily objects, from nail files to pliers to dental floss. Each case was different. Of course you couldn’t believe any of the things the prisoners said when they were turned over to you, their protestations of innocence. But even after it appeared you’d broken them, you couldn’t be sure they weren’t engaged in a more subtle deception, acting as if you’d succeeded in order to preserve the truly valuable information. For this reason, it was necessary to keep the interrogation open, to continue to revisit those prisoners who swore they’d told you everything they knew. These people are not like you and me, Just-Call-Me-Bill had said, confirming the impression that had dogged Vasquez when she’d walked patrol, past women draped in white or slate burqas, men whose pokool proclaimed their loyalty to the mujahideen. These are not a reasonable people, Bill went on. You cannot sit down and talk to them, come to an understanding with them. They would rather fly an airplane into a building full of innocent women and men. They would rather strap a bomb to their daughter and send her to give you a hug. They get their hands on a nuke, and there’ll be a mushroom cloud where Manhattan used to be. What they understand is pain. Enough suffering, and their tongues will loosen.

Vasquez could not pin down the exact moment Mr. White had joined their group. When he had shouldered his way past Lavalle and Maxwell, his left hand up to stop Plowman from tilting the prisoner backward, Just-Call-Me-Bill from pouring the water onto the man’s hooded face, she had thought, Who the hell? And, as quickly, Oh—Mr. White. He must have been with them for some time for Plowman to upright the prisoner, Bill to lower the bucket and step back. The flint knife in his right hand, its edge so fine you could feel it pressing against your bare skin, had not been unexpected. Nor had what had followed.

It was Mr. White who had suggested they transfer their operations to the Closet, a recommendation Just-Call-Me-Bill had been happy to embrace. Plowman, at first, had been noncommittal. Mr. White’s . . . call it his taking a more active hand in their interrogations . . . had led to him and Bill spending increased time together. Ruiz had asked the CIA man what he was doing with the man whose suit, while seemingly filthy, was never touched by any of the blood that slicked his knife, his hands. Education, Just-Call-Me-Bill had answered. Our friend is teaching me all manner of things.

As he was instructing the rest of them, albeit in more indirect fashion. Vasquez had learned that her father’s stories of the Villa Grimaldi, which he had withheld from her until she was fifteen, when over the course of the evening after her birthday she had been first incredulous, then horrified, then filled with righteous fury on his behalf, had little bearing on her duties in the Closet. Her father had been an innocent man, a poet, for God’s sake, picked up by Pinochet’s Caravana de la Muerte because they were engaged in a program of terrorizing their own populace. The men (and occasional women) at whose interrogations she assisted were terrorists themselves, spiritual kin to the officers who had scarred her father’s arms, his chest, his back, his thighs, who had scored his mind with nightmares from which he still fled screaming, decades later. They were not like you and me, and that difference authorized and legitimized whatever was required to start them talking.

By the time Mahbub Ali was hauled into the Closet, Vasquez had learned other things, too. She had learned that it was possible to concentrate pain on a single part of the body, to the point that the prisoner grew to hate that part of himself for the agony focused there. She had learned that it was preferable to work slowly, methodically—religiously, was how she thought of it, though this was no religion to which she’d ever been exposed. This was a faith rooted in the most fundamental truth Mr. White taught her, taught all of them—namely, that the flesh yearns for the knife, aches for the cut that will open it, relieve it of its quivering anticipation of harm. As junior member of the detail, she had not yet progressed to being allowed to work on the prisoners directly, but it didn’t matter. While she and Buchanan sliced away a prisoner’s clothes, exposed bare skin, what she saw there, a fragility, a vulnerability whose thick, salty taste filled her mouth, confirmed all of Mr. White’s lessons, every last one.

Nor was she his best student. That had been Plowman, the only one of them to whom Mr. White had entrusted his flint knife. With Just-Call-Me-Bill, Mr. White had maintained the air of a senior colleague; with the rest of them, he acted as if they were mannequins, placeholders. With Plowman, though, Mr. White was the mentor, the last practitioner of an otherwise-dead art passing his knowledge on to his chosen successor. It might have been the plot of a Steven Seagal film. And no Hollywood star could have played the eager apprentice with more enthusiasm than Plowman. While the official cause of Mahbub Ali’s death was sepsis resulting from improperly tended wounds, those missing pieces of the man had been parted from him on the edge of Mr. White’s stone blade, gripped in Plowman’s steady hand.

–

VI

Even with the clotted traffic, the cab drew up in front of the Concorde Opйra’s three sets of polished wooden doors with close to five hours to spare. While Vasquez settled with the driver, Buchanan stepped out of the cab, crossed the sidewalk, strode up three stairs, and passed through the center doors. The act distracted her enough that she forgot to ask for a receipt; by the time she remembered, the cab had accepted a trio of middle-aged women, their arms crowded with shopping bags, and pulled away. She considered chasing after it, before deciding that she could absorb the ten euros. She turned to the hotel to see the center doors open again, Buchanan standing in them next to a young man with a shaved head who was wearing navy pants and a cream tunic on whose upper left side a nametag flashed. The young man pointed across the street in front of the hotel and waved his hand back and forth, all the while talking to Buchanan, who nodded attentively. When the young man lowered his arm, Buchanan clapped him on the back, thanked him, and descended to Vasquez.

She said, “What was that about?”

“Shopping,” Buchanan said. “Come on.”

The next fifteen minutes consisted of them walking a route Vasquez wasn’t sure she could retrace, through clouds of slow-moving tourists stopping to admire some building or piece of public statuary; alongside briskly moving men and women whose ignoring those same sights marked them as locals as much as their chic haircuts, the rapid-fire French they delivered to their cell phones; past upscale boutiques and the gated entrances to equally upscale apartments. Buchanan’s route brought the two of them to a large corner building whose long windows displayed teddy bears, model planes, dollhouses. Vasquez said, “A toy store?”

“Not just a toy store,” Buchanan said. “This is the toy store. Supposed to have all kinds of stuff in it.”

“For your son.”

“Duh.”

Inside, a crowd of weary adults and overexcited children moved up and down the store’s aisles, past a mix of toys Vasquez recognized (Playmobil, groups of army vehicles, a typical assortment of stuffed animals) and others she’d never seen before (animal-headed figures she realized were Egyptian gods, replicas of round-faced cartoon characters she didn’t know, a box of a dozen figurines arranged around a cardboard mountain). Buchanan wandered up to her as she was considering this set, the box propped on her hip. “Cool,” he said, leaning forward. “What is it, like, the Greek gods?”

Vasquez resisted a sarcastic remark about the breadth of his knowledge; instead, she said, “Yeah. That’s Zeus and his crew at the top of the mountain. I’m not sure who those guys are climbing it . . .”

“Titans,” Buchanan said. “They were monsters who came before the gods, these kind of primal forces. Zeus defeated them, imprisoned them in the underworld. I used to know all their names: when I was a kid, I was really into myths and legends, heroes, all that shit.” He studied the toys positioned up the mountain’s sides. They were larger than the figures at its crown, overmuscled, one with an extra pair of arms, another with a snake’s head, a third with a single, glaring eye. Buchanan shook his head. “I can’t remember any of their names, now. Except for this guy,” he pointed at a figurine near the summit. “I’m pretty sure he’s Kronos.”

“Kronos?” The figure was approximately that of a man, although its arms, its legs, were slightly too long, its hands and feet oversized. Its head was surrounded by a corona of gray hair that descended into a jagged beard. The toy’s mouth had been sculpted with its mouth gaping, its eyes round, idiot. Vasquez smelled spoiled meat, felt the cardboard slipping from her grasp.

“Whoa.” Buchanan caught the box, replaced it on the shelf.

“Sorry,” Vasquez said. Mr. White had ignored her, strolling across the round chamber to the foot of the stairs, which he had climbed quickly.

“I don’t think that’s really Sam’s speed, anyway. Come on,” Buchanan said, moving down the aisle.

When they had stopped in front of a stack of remote-controlled cars, Vasquez said, “So who was Kronos?” Her voice was steady.

“What?” Buchanan said. “Oh—Kronos? He was Zeus’s father. Ate all his kids because he’d heard that one of them was going to replace him.”

“Jesus.”

“Yeah. Somehow, Zeus avoided becoming dinner and overthrew the old man.”

“Did he—did Zeus kill him?”

“I don’t think so. I’m pretty sure Kronos wound up with the rest of the Titans, underground.”

“Underground? I thought you said they were in the underworld.”

“Same diff,” Buchanan said. “That’s where those guys thought the underworld was, someplace deep underground. You got to it through caves.”

“Oh.”

In the end, Buchanan decided on a large wooden castle that came with a host of knights, some on horseback, some on foot; a trio of princesses; a unicorn; and a dragon. The entire set cost two hundred and sixty euros, which struck Vasquez as wildly overpriced, but which Buchanan paid without a murmur of protest—the extravagance of the present, she understood, being the point. Buchanan refused the cashier’s offer to gift-wrap the box, and they left the store with him carrying it under his arm.

Once on the sidewalk, Vasquez said, “Not to be a bitch, but what are you planning to do with that?”

Buchanan shrugged. “I’ll think of something. Maybe the front desk’ll hold it.”

Vasquez said nothing. Although the sky still glowed blue, the light had begun to drain out of the spaces among the buildings, replaced by a darkness that was almost granular. The air was warm, soupy. As they stopped at the corner, Vasquez said, “You know, we never asked Plowman about Lavalle or Maxwell.”

“Yeah, so?”

“Just—I wish we had. He had an answer for everything else; I wouldn’t have minded hearing him explain that.”

“There’s nothing to explain,” Buchanan said.

“We’re the last ones alive—”

“Plowman’s living. So’s Mr. White.”

“Whatever—you know what I mean. Christ, even Just-Call-Me-Bill is dead. What the fuck’s up with that?”

In front of them, traffic stopped. The walk signal lighted its green man. They joined the surge across the street. “It’s a war, Vasquez,” Buchanan said. “People die in them.”

“Is that what you really believe?”

“It is.”

“What about your freak-out before, at the tower?”

“That’s exactly what it was—me freaking out.”

“Okay,” Vasquez said after a moment, “okay. Maybe Bill’s death was an accident—maybe Maxwell, too. What about Lavalle? What about Ruiz? You telling me it’s normal two guys from the same detail try to off themselves?”

“I don’t know.” Buchanan shook his head. “You know the army isn’t big on mental-health care. And let’s face it; that was some pretty fucked-up shit went on in the Closet. Not much of a surprise if Lavalle and Ruiz couldn’t handle it, is it?”

Vasquez waited another block before asking, “How do you deal with it—the Closet?”

Buchanan took one more block after that to answer: “I don’t think about it.”

“You don’t?”

“I’m not saying the thought of what we did over there never crosses my mind, but as a rule, I focus on the here and now.”

“What about the times the thought does cross your mind?”

“I tell myself it was a different place with different rules. You know what I’m talking about. You had to be there; if you weren’t, then shut the fuck up. Maybe what we did went over the line, but that’s for us to say, not some panel of officers don’t know their ass from a hole in the ground, and damn sure not some reporter never been closer to war than a goddamn showing of Platoon.” Buchanan glared. “You hear me?”

“Yeah.” How many times had she used the same arguments, or close enough, with her father? He had remained unconvinced. So only the criminals are fit to judge the crime? he had said. What a novel approach to justice. She said, “You know what I hate, though? It isn’t that people look at me funny—Oh, it’s her—it isn’t even the few who run up to me in the supermarket and tell me what a disgrace I am. It’s like you said: they weren’t there, so fuck ’em. What gets me are the ones who come up to you and tell you, ‘Good job, you fixed them Ay-rabs right,’ the crackers who wouldn’t have anything to do with someone like me, otherwise.”

“Even crackers can be right, sometimes,” Buchanan said.

–

VII

Mr. White’s room was on the sixth floor, at the end of a short corridor that lay around a sharp left turn. The door to the junior suite appeared unremarkable, but it was difficult to be sure, since both the bulbs in the wall sconces on either side of the corridor were out. Vasquez searched for a light switch and, when she could not find one, said, “Either they’re blown, or the switch is inside his room.”

Buchanan, who had been unsuccessful in convincing the woman at the front desk to watch his son’s present, was busy fitting it beneath one of the chairs to the right of the elevator door.

“Did you hear me?” Vasquez asked.

“Yeah.”

“Well?”

“Well what?”

“I don’t like it. Our visibility’s fucked. He opens the door, the light’s behind him, in our faces. He turns on the hall lights, and we’re blind.”

“For, like, a second.”

“That’s more than enough time for Mr. White to do something.”

“Will you listen to yourself?”

“You saw what he could do with that knife.”

“All right,” Buchanan said, “how do you propose we deal with this?”

Vasquez paused. “You knock on the door. I’ll stand a couple of feet back with my gun in my pocket. If things go pear shaped, I’ll be in a position to take him out.”

“How come I have to knock on the door?”

“Because he liked you better.”

“Bullshit.”

“He did. He treated me like I wasn’t there.”

“That was the way Mr. White was with everyone.”

“Not you.”

Holding his hands up, Buchanan said, “Fine. Dude creeps you out so much, it’s probably better I’m the one talking to him.” He checked his watch. “Five minutes till showtime. Or should I say, ‘T minus five and counting,’ something like that?”

“Of all the things I’m going to miss about working with you, your sense of humor’s going to be at the top of the list.”

“No sign of Plowman, yet.” Buchanan checked the panel next to the elevator, which showed it on the third floor.

“He’ll be here at precisely eleven ten.”

“No doubt.”

“Well . . .” Vasquez turned away from Buchanan.

“Wait—where are you going? There’s still four minutes on the clock.”

“Good. It’ll give our eyes time to adjust.”

“I am so glad this is almost over,” Buchanan said, but he accompanied Vasquez to the near end of the corridor to Mr. White’s room. She could feel him vibrating with a surplus of smart-ass remarks, but he had enough sense to keep his mouth shut. The air was cool, floral scented with whatever they’d used to clean the carpet. Vasquez expected the minutes to drag by, for there to be ample opportunity for her to fit the various fragments of information in her possession into something like a coherent picture; however, it seemed that practically the next second after her eyes had adapted to the shadows leading up to Mr. White’s door, Buchanan was moving past her. There was time for her to slide the pistol out from under her blouse and slip it into the right front pocket of her slacks, and then Buchanan’s knuckles were rapping the door.

It opened so quickly, Vasquez almost believed Mr. White had been positioned there, waiting for them. The glow that framed him was soft, orange, an adjustable light dialed down to its lowest setting, or a candle. From what she could see of him, Mr. White was the same as ever, from his unruly hair, more gray than white, to his dirty white suit. Vasquez could not tell whether his hands were empty. In her pocket, her palm was slick on the pistol’s grip.

At the sight of Buchanan, Mr. White’s expression did not change. He stood in the doorway regarding the man, and Vasquez three feet behind him, until Buchanan cleared his throat and said, “Evening, Mr. White. Maybe you remember me from Bagram. I’m Buchanan; my associate is Vasquez. We were part of Sergeant Plowman’s crew; we assisted you with your work interrogating prisoners.”

Mr. White continued to stare at Buchanan. Vasquez felt panic gathering in the pit of her stomach. Buchanan went on, “We were hoping you would accompany us on a short walk. There are matters we’d like to discuss with you, and we’ve come a long way.”

Without speaking, Mr. White stepped into the corridor. The fear, the urge to sprint away from here as fast as her legs would take her, that had been churning in Vasquez’s gut, leapt up like a geyser. Buchanan said, “Thank you. This won’t take five minutes—ten, tops.”

Behind her, the floor creaked. She looked back, saw Plowman standing there, and in her confusion, did not register what he was holding in his hand. Someone coughed, and Buchanan collapsed. They coughed again, and it was as if a snowball packed with ice struck Vasquez’s back low and to the left.

All the strength left her legs. She sat down where she was, listing to her right until the wall stopped her. Plowman stepped over her. The gun in his right hand was lowered; in his left, he held a small box. He raised the box, pressed it, and the wall sconces erupted in deep purple-black light, by whose illumination Vasquez saw the walls, the ceiling, the carpet of the short corridor covered in symbols drawn in a medium that shone pale white. She couldn’t identify most of them. She thought she saw a scattering of Greek characters, but the rest were unfamiliar: circles bisected by straight lines traversed by short, wavy lines; a long, gradual curve like a smile; more intersecting lines. The only figure she knew for sure was a circle whose thick circumference was broken at about the eight o’clock point, inside which Mr. White was standing and Buchanan lying. Whatever Plowman had used to draw them made the symbols appear to float in front of the surfaces on which he’d marked them, strange constellations crammed into an undersized sky.

Plowman was speaking, the words he was uttering unlike any Vasquez had heard, thick ropes of sound that started deep in his throat and spilled into the air squirming, writhing over her eardrums. Now Mr. White’s face showed emotion: surprise, mixed with what might have been dismay, even anger. Plowman halted next to the broken circle and used his right foot to roll Buchanan onto his back. Buchanan’s eyes were open, unblinking, his lips parted. The exit wound in his throat shone darkly. His voice rising, Plowman completed what he was saying, gestured with both hands at the body, and retreated to Vasquez.

For an interval of time that lasted much too long, the space where Mr. White and Buchanan were was full of something too big, which had to double over to cram itself into the corridor. Eyes the size of dinner plates stared at Plowman, at Vasquez, with a lunacy that pressed on her like an animal scenting her with its sharp snout. Amidst a beard caked and clotted with offal, a mouth full of teeth cracked and stained black formed sounds Vasquez could not distinguish. Great, pale hands large as tires roamed the floor beneath the figure—Vasquez was reminded of a blind man investigating an unfamiliar surface. When the hands found Buchanan, they scooped him up like a doll and raised him to that enormous mouth.

Groaning, Vasquez tried to roll away from the sight of Buchanan’s head surrounded by teeth like broken flagstones. It wasn’t easy. For one thing, her right hand was still in her pants pocket, its fingers tight around the Walther, her wrist and arm bent in at awkward angles. (She supposed she should be grateful she hadn’t shot herself.) For another thing, the cold that had struck her back was gone, replaced by heat, by a sharp pain that grew sharper still as she twisted away from the snap and crunch of those teeth biting through Buchanan’s skull. God. She managed to move onto her back, exhaling sharply. To her right, the sounds of Buchanan’s consumption continued, bones snapping, flesh tearing, cloth ripping. Mr. White—what had been Mr. White, or what he truly was—that vast figure was grunting with pleasure, smacking its lips together like someone starved for food given a gourmet meal.

“For what it’s worth,” Plowman said, “I wasn’t completely dishonest with you.” One leg to either side of hers, he squatted over her, resting his elbows on his knees. “I do intend to bring Mr. White into my service; it’s just the methods necessary for me to do so are a little extreme.”

Vasquez tried to speak. “What . . . is he?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Plowman said. “He’s old—I mean, if I told you how old he is, you’d think . . .” He looked to his left, to the giant sucking the gore from its fingers. “Well, maybe not. He’s been around for a long time, and he knows a lot of things. We—what we were doing at Bagram, the interrogations, they woke him. I guess that’s the best way to put it; although you could say they called him forth. It took me a while to figure out everything, even after he revealed himself to me. But there’s nothing like prison to give you time for reflection. And research.

“That research says the best way to bind someone like Mr. White is—actually, it’s pretty complicated.” Plowman waved his pistol at the symbols shining around them. “The part that will be of most immediate interest to you is the sacrifice of a man and woman who are in my command. I apologize. I intended to put the two of you down before you knew what was happening; I mean, there’s no need to be cruel about this. With you, however, I’m afraid my aim was off. Don’t worry. I’ll finish what I started before I turn you over to Mr. White.”

Vasquez tilted her right hand up and squeezed the trigger of her gun. Four pops rushed one after the other, blowing open her pocket. Plowman leapt back, stumbled against the opposite wall. Blood bloomed across the inner thigh of his trousers, the belly of his shirt. Wiped clean by surprise, his face was blank. He swung his gun toward Vasquez, who angled her right hand down and squeezed the trigger again. The top of Plowman’s shirt puffed out; his right eye burst. His arm relaxed, his pistol thumped on the floor, and, a second later, he joined it.

The burn of suddenly hot metal through her pocket sent Vasquez scrambling up the wall behind her before the pain lodged in her back could catch her. In the process, she yanked out the Walther and pointed it at the door to the junior suite—

–in front of which Mr. White was standing, hands in his jacket pockets. A dark smear in front of him was all that was left of Buchanan. Jesus God . . . The air reeked of black powder and copper. Across from her, Plowman stared at nothing through his remaining eye. Mr. White regarded her with something like interest. If he moves, I’ll shoot, Vasquez thought, but Mr. White did not move, not the length of time it took her to back out of the corridor and retreat to the elevator, the muzzle of the pistol centered on Mr. White, then on where Mr. White would have been if he’d rounded the corner. Her back was a knot of fire. When she reached the elevator, she slapped the call button with her left hand while maintaining her aim with her right. Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Buchanan’s gift for his son, all two hundred and sixty euros’ worth, wedged under its chair. She left it where it was. A faint glow shone from the near end of the corridor: Plowman’s black-lighted symbols. Was the glow changing, obscured by an enormous form crawling toward her? When the elevator dinged behind her, she stepped into it, the gun up in front of her until the doors had closed and the elevator had commenced its descent.

The back of her blouse was stuck to her skin; a trickle of blood tickled the small of her back. The interior of the elevator dimmed to the point of disappearing entirely. The Walther weighed a thousand pounds. Her legs wobbled madly. Vasquez lowered the gun, reached her left hand out to steady herself. When it touched not metal, but cool stone, she was not as surprised as she should have been. As her vision returned, she saw that she was in a wide, circular area, the roof flat, low, the walls no more than shadowy suggestions. The space was lit by a symbol incised on the rock at her feet: a rough circle, the diameter of a manhole cover, broken at about eight o’clock, whose perimeter was shining with cold light. Behind and to her left, the scrape of bare flesh dragging over stone turned her around. This section of the curving wall opened in a black arch like the top of an enormous throat. Deep in the darkness, she could detect movement, but was not yet able to distinguish it.

As she raised the pistol one more time, Vasquez was not amazed to find herself here, under the ground with things whose idiot hunger eclipsed the span of the oldest human civilizations, things she had helped summon. She was astounded to have thought she’d ever left.

–

For Fiona.

–

John Langan is the author of the novel House of Windows and the collection of stories Mr. Gaunt and Other Uneasy Encounters. His stories have appeared in Fantasy & Science Fiction and Poe: 19 New Tales Inspired by Edgar Allan Poe. He lives in upstate New York with his wife and son.

–

Ellen Datlow has been editing science fiction, fantasy, and horror short fiction for over twenty-five years. She was fiction editor of Omni and Sci Fiction and has edited more than fifty anthologies, including the horror half of the long-running The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, the current The Best Horror of the Year, Inferno, Poe: 19 New Tales Inspired by Edgar Allan Poe, Lovecraft Unbound, Darkness: Two Decades of Modern Horror, Tails of Wonder and Imagination, Digital Domains: A Decade of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Naked City: Tales of Urban Fantasy, The Beastly Bride and Other Tales of the Animal People, Teeth: Vampire Tales (the latter two with Terri Windling), and Haunted Legends (with Nick Mamatas).

Forthcoming is Blood and Other Cravings and After (the last with Windling).

She has won multiple Locus Awards, Hugo Awards, Stoker Awards, International Horror Guild Awards, World Fantasy Awards, and Shirley Jackson Awards for her editing. She was named recipient of the 2007 Karl Edward Wagner Award, given at the British Fantasy Convention for “outstanding contribution to the genre.”

She lives in New York. More information can be found at Datlow.com or at her blog: Ellen-Datlow.LiveJournal.com.